by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Image: Childe Hassam, To the 101st (Massachusetts) Infantry. Oil on canvas, 1918. Collection of Jonathan L. Cohen

Childe Hassam’s To the 101st (Massachusetts) Infantry, featured in the Florence Griswold Museum’s fall 2017 exhibition World War I and the Lyme Art Colony, captures the riveting scene of a young soldier’s leave-taking on a sparkling summer morning in 1918. The painting depicts the artist’s khaki-clad cousin lingering on a doorstep before departing from Gloucester. Similar moments of poignant farewell occurred in Old Lyme, where some 75 men served in the armed forces after America entered the Great War in April 1917.[1]

Strict censorship prevented those attached to the American Expeditionary Force from describing their wartime experience in France. Letters from soldiers in difficult and dangerous surroundings maintained a lighthearted tone to comply with censorship restrictions, reassure family and friends, and sustain their own morale amid loneliness, discomfort, and fear. The stream of mail that Helen Clark (1892–1988) received in Old Lyme during the war years offered only guarded comments about circumstances faced by town “fellows” serving in the A.E.F. Prohibited from writing about their circumstances, they filled letters written “Somewhere in France” with comments about mail received, banter about mutual friends, and questions about hometown activities.

Helen Clark, ca. 1918. Courtesy Janet Speirs York

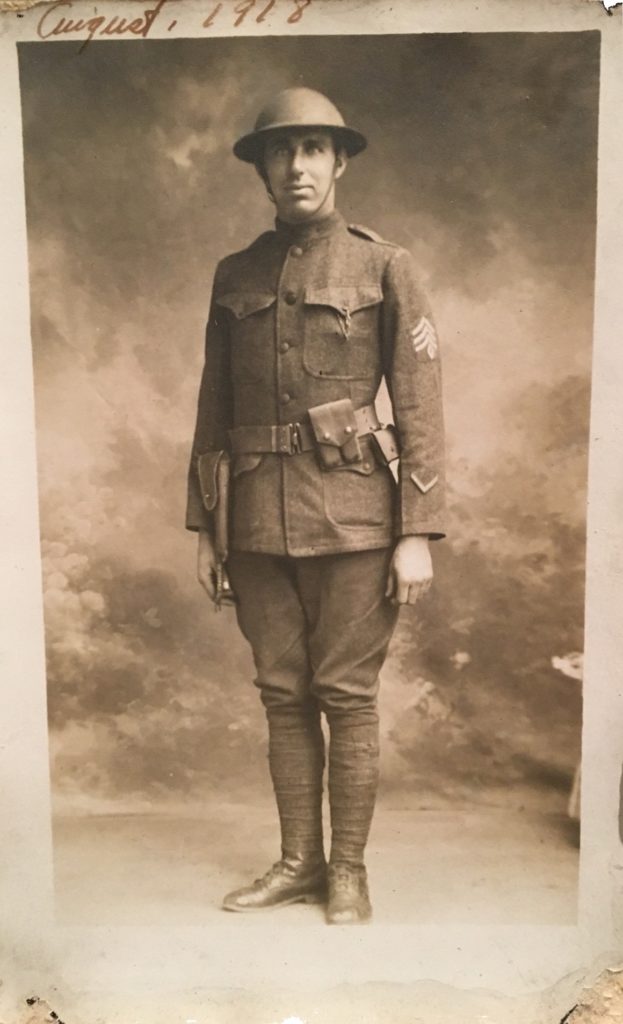

John J. Speirs, August 1918. Courtesy Janet Speirs York

John J. Speirs, August 1918. Courtesy Janet Speirs York

Helen’s future husband Jack Speirs (1890–1984) reported for training at newly established Camp Dix in New Jersey in September 1917. During hasty preparation for deployment, he and two close friends from Old Lyme joined engineering regiments that specialized in water supply. They kept busy drilling three or four hours a day, he wrote to Helen on September 24, and he had gotten over his initial “lameness.” He had been issued a uniform, he didn’t “have a bit of fault to find with the food,” but he did worry about being vaccinated when he “didn’t believe in it very much.” A month later on October 28, he wrote: “No time to sit around the barracks now. . . .I feel quite sure we will leave here either Sunday night or Monday.”

Gas Warfare Training at Camp Dix, 1917. National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/26423932

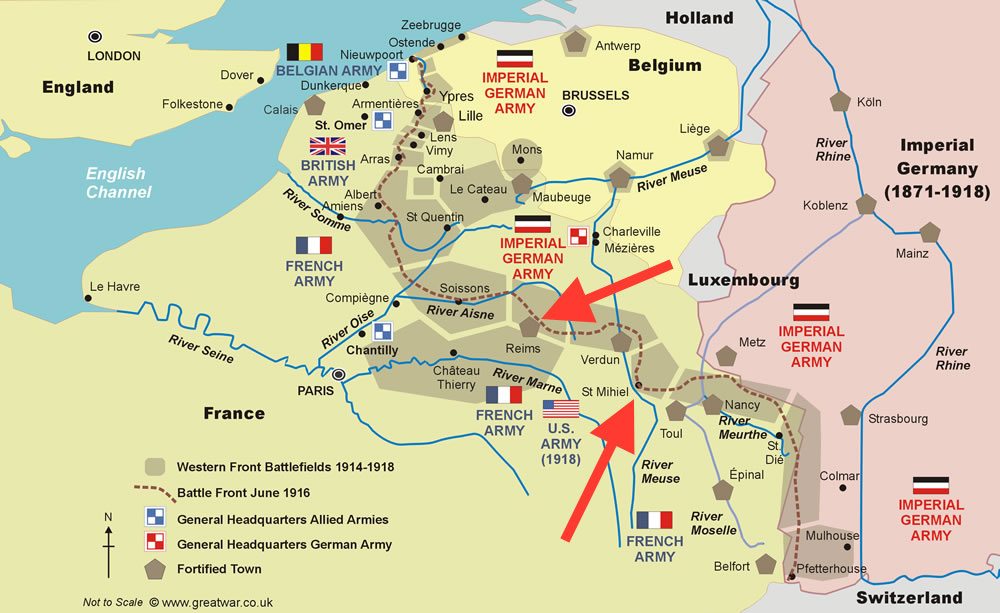

Location of the 1914–1918 Battlefields of the Western Front, showing area of preparation for the successful attack on St. Mihiel by A.E.F. troops http://www.greatwar.co.uk/places/ww1-western-front.htm

After disembarking at Brest on November 17, the 26th Engineers constructed plumbing and sewage systems for a 300-bed hospital at the port of St. Nazaire, an essential debarkation point during the rapid build-up of American forces. That winter they moved closer to the front to establish water supply facilities in the Second Infantry Division’s training area. “The men were obliged to live in old, crumbling stone structures in the village of Bourmont, the best billets the humble town afforded,” a regimental history records. Starting in May the engineers “worked under new conditions” behind the front lines to lay water pipes and establish water-holding systems in a recently re-occupied area in advance of the St. Mihiel offensive. By August 1918 “there were but few members of the Company who did not have opportunity to experience the enemy’s fire, both from machine guns and artillery,” the regimental history states.[2]

Edmund Greacen, Reims, 1918. Oil on beaver board. Collection of Renée Faure, granddaughter of the artist

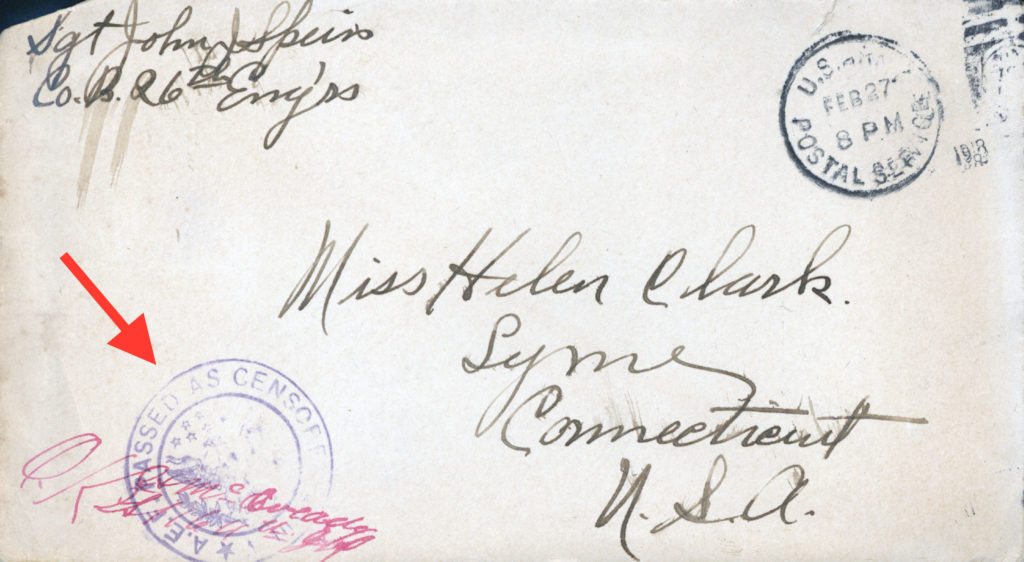

Helen’s cousin Charles F. Watrous from Essex was assigned to the 102nd U.S. Infantry after training at Camp Devens in Massachusetts.[3] A letter written “Somewhere in France” on December 2, 1917, said “we are all having a lot of experience and don’t you think for a minute that we are not.” Two weeks later Charles noted that he didn’t know what to write about “as things that I would like to tell you about we can’t so you see we are kind of handicapped for writing.” He added that they were no longer living in tents but in billets, “which are rather better this time of year.” Jack Speirs also commented on the weather in a letter to Helen at the end of February 1918: “The mud is pretty bad over here again and we are having rainy weather, outside of that everything is fine, and that won’t hurt us.” The envelope, stamped “A.E.F. Passed Censorship,” shows the censor’s “O.K.” beside his initials in red ink.

Jack Speirs to Helen Clark, February 24, 1918, showing censorship stamp. Courtesy Janet Speirs York

Before leaving the rear area, Jack and his two friends wrote an open letter on April 14, 1918, “To Our Fellow Townspeople” that appeared in The New London Day.[4] Eager for mail from home, they remarked wryly that perhaps some friends not yet heard from “can’t write or have had some serious accident, thus incapacitating them.” They also jokingly welcomed others to join them in “sunny France,” where so far they had seen three days of sunshine, and they jested about those still in training camps and “eagerly awaiting their departure.” After one winter with the A.E.F., they would likely “change their ideas on the joys of soldiering.”

Daniel Moore, John J. Speirs, Thomas Appleby “To Our Fellow Townspeople,” April 14, 1918, The New London Day. Scrapbooks, Lyme Historical Society Archive (LHSA) at the Florence Griswold Museum

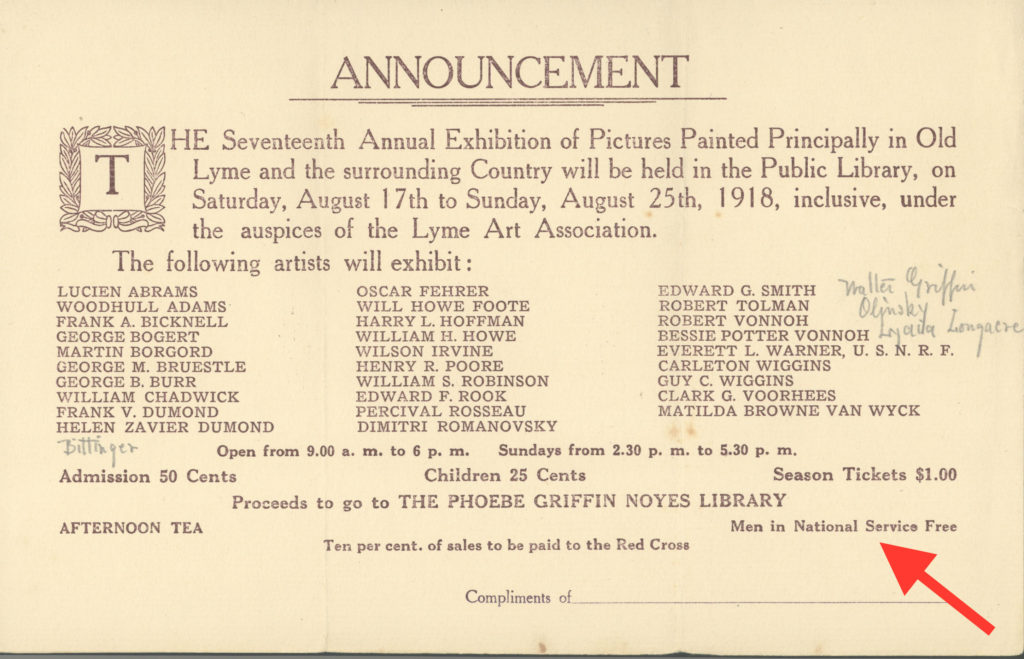

Despite a lighthearted tone the engineers’ remarks about those who “joined the colors” but remained safely at home hinted at the hazards of wartime. Perhaps members of the local Home Guard had dropped “from a troop train at some isolated place on the shore line” to secure possession of a village, they wrote, “only to find they had carried their home town by storm.” Humorous remarks about those remaining safely at home included mention of an Old Lyme art colony member known for his paintings of snow scenes. “We also hear that Lt. E. G. Smith went over the top,” the engineers wrote, “but it was only a snow bank, one dark and stormy night last winter.” In August Edward G. Smith (1880-1961) exhibited a painting titled Winter Sun at Old Lyme’s annual summer art show, which in 1918 admitted men in national service for free.

Announcement of the Lyme Art Association’s Seventeenth Annual Exhibition of Pictures, August 17 to August 25, 1918. LHSA

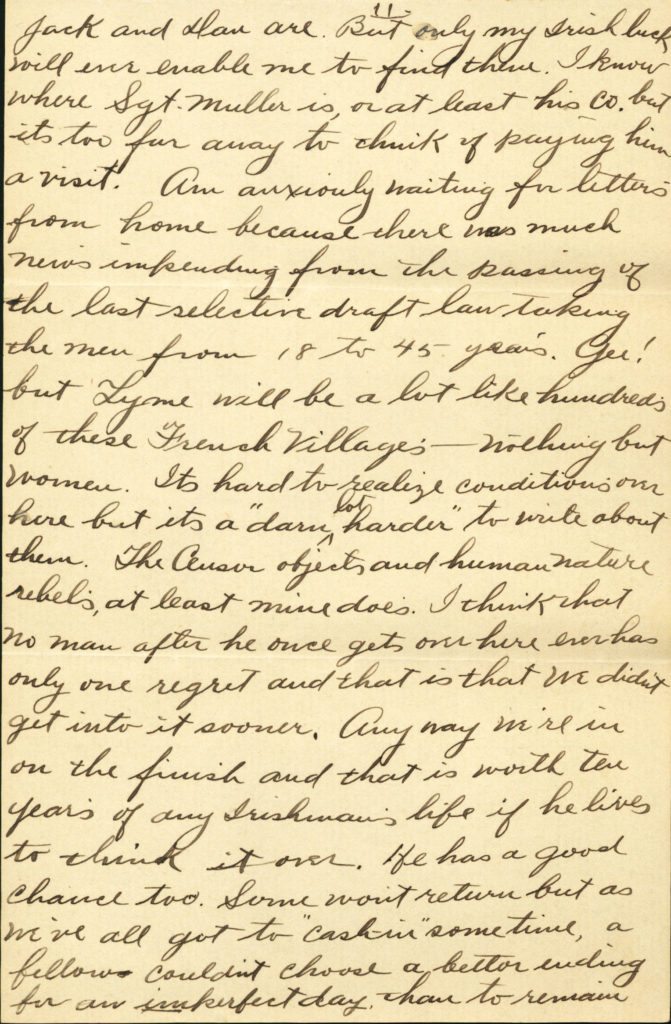

While most of Helen’s friends avoided mentioning danger and discomfort, Harold Bump, a relative by marriage, commented with “grim humor” on the “joys” of soldiering. Sgt. Bump, drafted in 1918, reached France in early July with the 303rd infantry regiment that provided fresh troops for the depleted front lines. “Dear Pal,” he wrote six weeks later in graceful script covering six pages. It is “hard to realize conditions over here, but it’s a darn lot harder to write about them. The censor objects and human nature rebels, at least mine does.”

Sgt. Harold Bump to Helen Clark, August 11, 1918. Courtesy Janet Speirs York

Sgt. Bump assured Helen that her friends in the water-supply company “were in an entirely different line of business” and wouldn’t “see the same things, at least I hope they don’t have to.” But he mentioned another Old Lyme friend Dan Appleby who drove mules in a supply train and “fully expected to be blowed plumb to hell, mules and all, anytime.” Harold joked that some serving in France wouldn’t return, “but as we’ve all got to ‘cash-in’ sometime, a fellow couldn’t choose a better ending for an imperfect day than to remain over here to promote the future daisy crop.” He also remarked on the difficult conditions of “rest billets” for war-weary troops. “A decent Hobo would kick against being put into them but we are tickled to death,” he wrote, then offered a lighthearted description of his first infestation with body lice.

George Hand Wright, Battle Scene, World War I. Charcoal and watercolor on brown paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Edward F. Gerber

While writing almost daily to friends serving in France, Helen Clark worked as assistant to Katharine Ludington (1869–1963), who as president of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association promoted women’s war work while leading the fight for a woman’s right to vote. Helen took charge of local food conservation efforts. “As many people are wanting to buy vegetables for canning etc., and others have a surplus of perishable garden truck, which they would be glad to dispose of, the experiment of a bulletin board in the Old Lyme post office is to be tried,” The New London Day reported on July 9, 1917. “Anyone who has stuff to sell will notify Miss Helen Clark, phone 95, before 9:30 a.m. and state what they have and the price. Miss Clark can be found at Miss Ludington’s.” Helen also worked as assistant postmistress and assistant librarian, and from 1917 to 1920 she served on the Board of Education, the first woman to hold elected office in Old Lyme.

Helen Clark and her brother Clarence, Old Lyme Post Office, ca. 1910. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

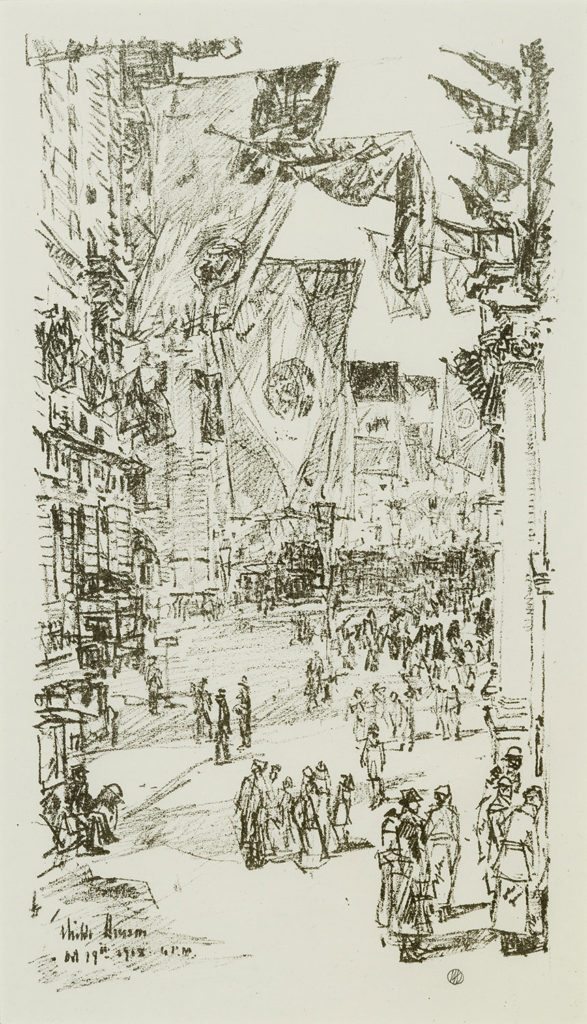

Childe Hassam, Avenue of the Allies, 1918. Lithograph. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase

Flags festooned New York’s streets and crowds celebrated when the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, but the work of American water-supply troops did not end. As an occupying force of men and horses rushed to Germany, A.E.F. engineering regiments provided essential water facilities along the route. Jack’s friend Dan Moore wrote to Helen in November that he hoped soon to be out of work and heading back, noting that he hadn’t seen the sun in two months. “It sure is lovely here in the mud,” he said. Nor did the war’s end remove the risks faced by those who continued to serve in France. Tom Appleby, Jack’s companion since their enlistment in New London in May 1917, died suddenly of pneumonia at an army hospital in January 1919. The news was “a dreadful shock to everyone,” Helen wrote. “It’s a pretty hard blow when he was expected to drop in any time.”

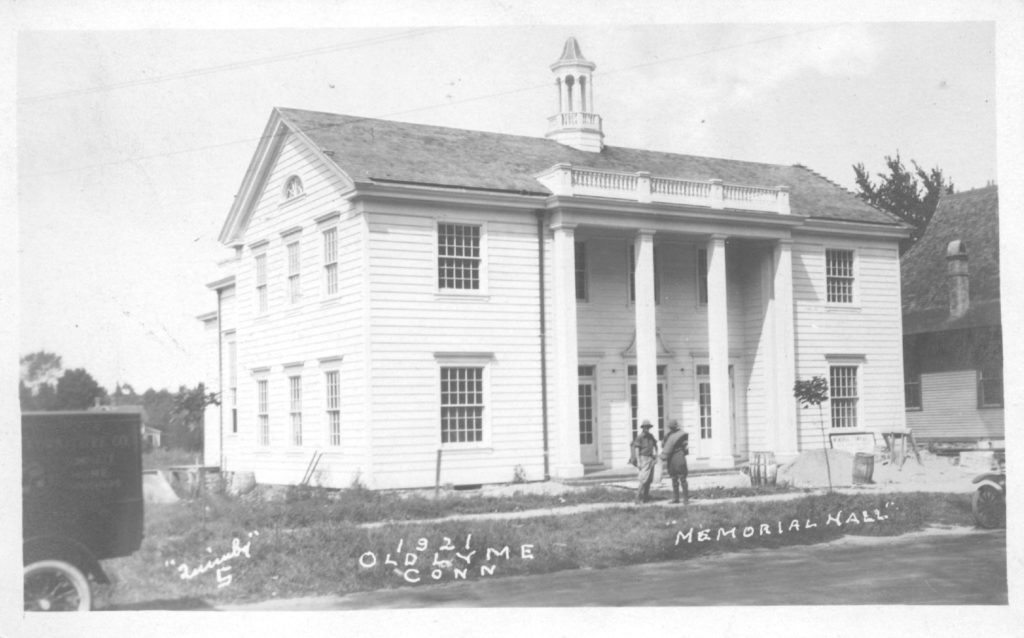

Jack Speirs and Helen Clark married in February 1920, almost a year after his return from France. As commander of the local American Legion post, he laid the cornerstone for a new Town Hall honoring those who had served in World War I. When the Memorial Town Hall opened on Armistice Day in 1921, the Congregational Church bell tolled continuously at twelve noon during a solemn ceremony of dedication.[5]

Postcard, showing landscaping of Memorial Hall, 1921. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

Almost a century later the Town Hall bears witness to those who left home for “Somewhere in France.” Harry T. Griswold (1879–1963), a civil engineer with the New London firm of Payne, Griswold & Keefe who spent more than a year as an officer with American troops in France, designed the town’s modern office building. His eldest brother Dr. Richard S. Griswold (1869–1901) had been killed in the Philippines during the Spanish American War, another brother George Griswold (1876–1939) had served during World War I in the engineering corps, and a third brother Dr. James Griswold (1870–1917), a surgeon in Morristown, New Jersey, had died of illness at Camp Dix in October 1917 before being deployed. Three weeks earlier Jack Speirs had written to Helen, “I had a nice talk with Jim Griswold.”[6]

Albert Herter, Spirit of a Doughboy, 1918, Old Lyme Memorial Town Hall, http://www.theday.com/article/20130815/NWS01/308159983

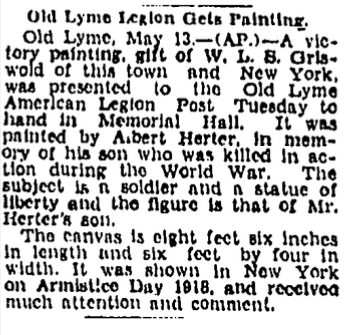

A monumental pastel portrait of Lady Liberty embracing a “doughboy,” donated to Old Lyme’s American Legion Post by W.E.S. Griswold in 1931, still hangs above the central stairway in the Memorial Town Hall. Albert Herter (1871–1950), a New York artist and muralist who had lost a son on the battlefield, had studied in France before the war, and his wife posed for the female figure in Spirit of a Doughboy, created as a memorial to their son Everit Albert Herter (1894–1918). A Harvard graduate and a sergeant in the 40th Engineers, Everit Herter, also an artist, had joined the army’s Camouflage Corps soon after its creation in July 1917. He died, age 24, after being hit by a bursting shell while camouflaging a gun position at Chateau-Thierry in June 1918.[7] Albert Herter’s tribute to his son hung in New York on Armistice Day, 1918.

“Old Lyme Legion Gets Painting,” Hartford Courant, May 14, 1931

[1] Special thanks to Janet Speirs York and Amy Kurtz Lansing for generous assistance. See Connecticut Men and Women in the Armed Forces of the United States during World War I, Vol.2, pp. 2327-2329 (Hartford, 1940); Benjamin Tinkham Marshall, A Modern History of New London County Connecticut (New York, 1922), p. 612.

[2]“Company B,” History of the Twenty-Sixth Engineers (Water Supply Regiment) in the World War, September 1917-March, 1919 (n.d.), pp. 29-42.

[3] See also Finding Aid, Charles Watrous Papers, Connecticut State Library. https://ctstatelibrary.org/RG069_145.html

[4] “Old Lyme Boys Abroad Lonesome,” The New London Day (n.d.). LHSA

[5] Carolyn Wakeman, The Charm of the Place: Old Lyme in the 1920s (Old Lyme Historical Society, 2011), pp. 25-26.

[6] See “The Story of Morristown’s World War I Monument.” https://morristowngreen.com/2017/05/25/the-story-of-morristowns-world-war-i-monument/

[7] “’Spirit of the Doughboy’ Is ‘Back Where It Belongs’ at Old Lyme’s Memorial Town Hall” (April 23, 2013), LymeLine http://lymeline.com/2013/04/spirit-of-the-doughboy-returns-to-old-lymes-memorial-town-hall-public-reception-to-be-held-april-22/; “Art Restored,” Old Lyme Patch (April 23, 2013) https://patch.com/connecticut/thelymes/the-daily-five_069dba05; Betty J. Cotter, “Some Real Gems Hanging on Region’s Public Walls,” The New London Day (April 15, 2013) http://www.theday.com/article/20130815/NWS01/308159983;“Camouflage Artist Everit Herter” (December 7, 2013); http://camoupedia.blogspot.com/2013/12/camouflage-artist-everit-herter.html