Documents

Exhibition Notes: Matilda Browne’s Historic Lyme Street House, Part I—After the Revolution

ON May 25, 2017

by Carolyn Wakeman

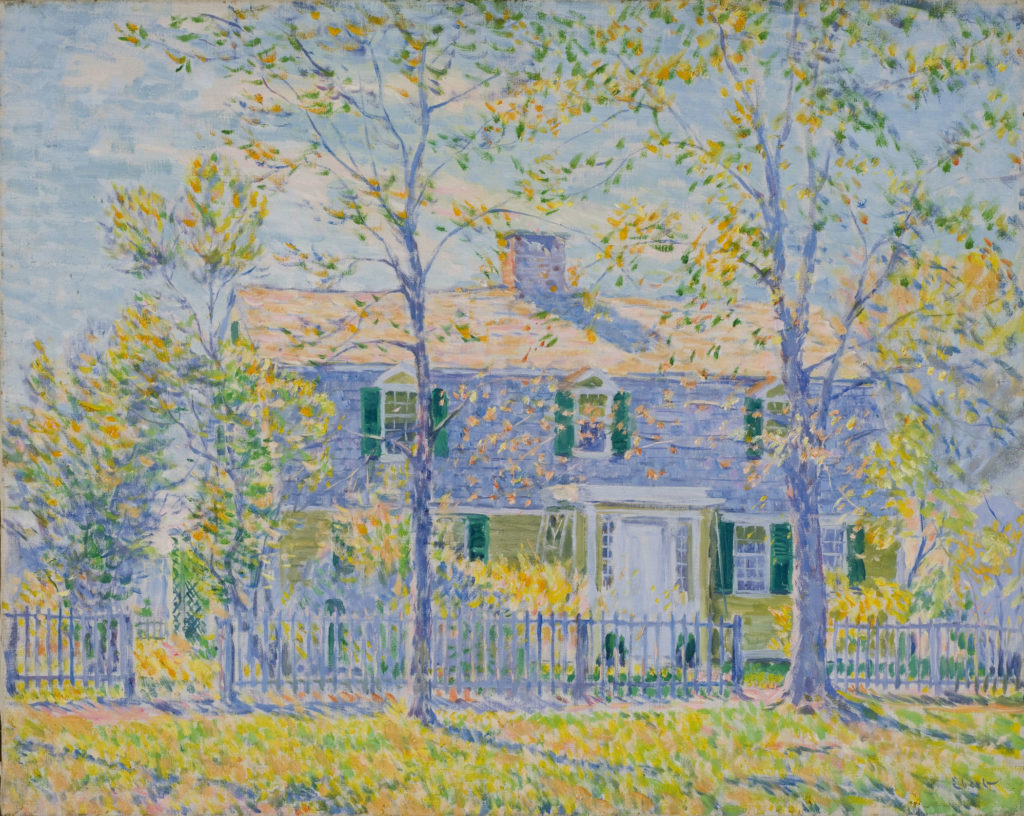

Feature Image: Matilda Browne, Untitled [Yellow House with Yellow Roses], after 1918. Oil on wood. Private Collection

The colonial-era house on Lyme Street where artist Matilda Browne (1869–1947) lived for four years during the aftermath of World War I has stories to tell. A captivating painting of her house and gardens in dappled summer sunlight hangs in the Florence Griswold Museum’s stunning spring 2017 exhibition Matilda Browne: Idylls of Farm and Garden. Using a vibrant palette of yellows and greens, the artist captures the antiquity and charm of her gambrel-roofed dwelling with its tree-shaded yard and old-fashioned bed of roses and hollyhocks in fullest bloom. The painting, an untitled view of a yellow house with yellow roses, invites us to share that fleeting summer moment, but its air of nostalgia also draws us back to an earlier time.

Matilda Browne, ca. 1915. Private Collection

Matilda Browne’s Old Lyme Purchase

Matilda Browne made repeated visits to Old Lyme over more than a decade before buying an “old-fashioned homestead” in the center of the village. In 1905 she painted a pair of door panels in the dining room of Florence Griswold’s (1850–1837) house, where many of the country’s most talented landscape painters boarded for weeks at a time. In 1911 she joined the artists gathered in the once-elegant mansion on upper Lyme Street and shared studio space in a “rickety” old barn with Woodrow Wilson’s wife, artist Ellen Axson Wilson (1860–1914).[1]

On other visits Matilda Browne lodged at the Old Lyme Inn, sometimes with one of her sisters, and in 1914 she painted two luminous portraits of the 18th-century gambrel-roofed house beside the Connecticut River that fellow artist Clark Voorhees (1871–1933) had purchased in 1903.[2] After her marriage in 1917 to Frederick Van Wyck (1853–1936), she bought her own Dutch colonial home in the center of the village.

Matilda Browne, In Voorhees’s Garden, 1914. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Matilda Browne, Clark Voorhees House, ca. 1905. Oil on board. Florence Griswold Museum

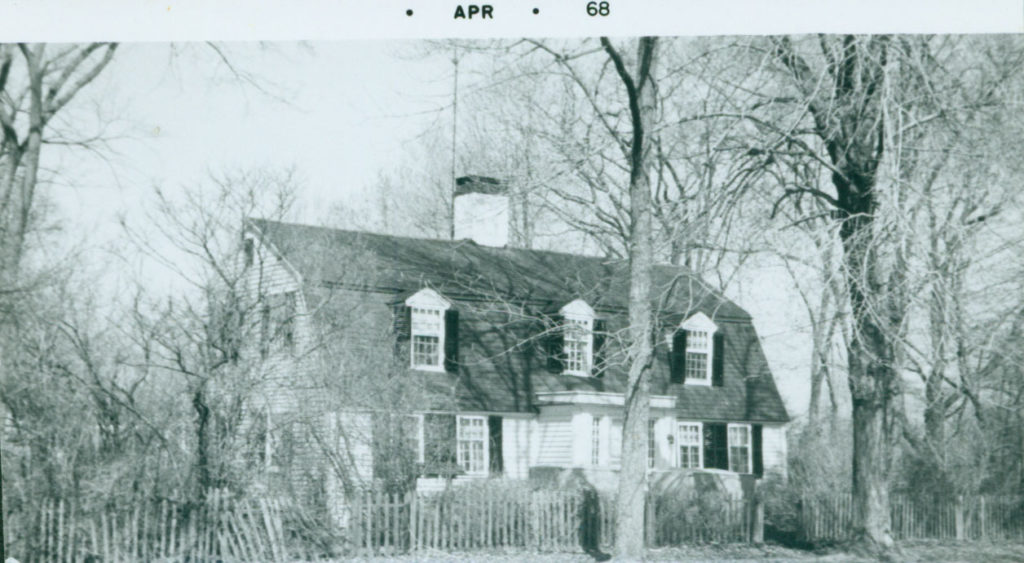

The well-preserved 18th-century houses dotting Old Lyme’s landscape contributed to the nostalgic sense of a place apart from modernization’s blight. The house that Matilda Browne purchased, like the three-gabled dwelling farther north on Lyme Street owned briefly by fellow artist George Bogert (1864–1944) and painted by Charles Ebert (1873–1959), pre-date the Revolution.

Charles Ebert, House on Lyme Street, n.d. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Elisabeth Ebert

Lyme Street House owned briefly by George Bogert, purchased in 1969 by Senator Thomas Dodd, 1968. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA/FGM)

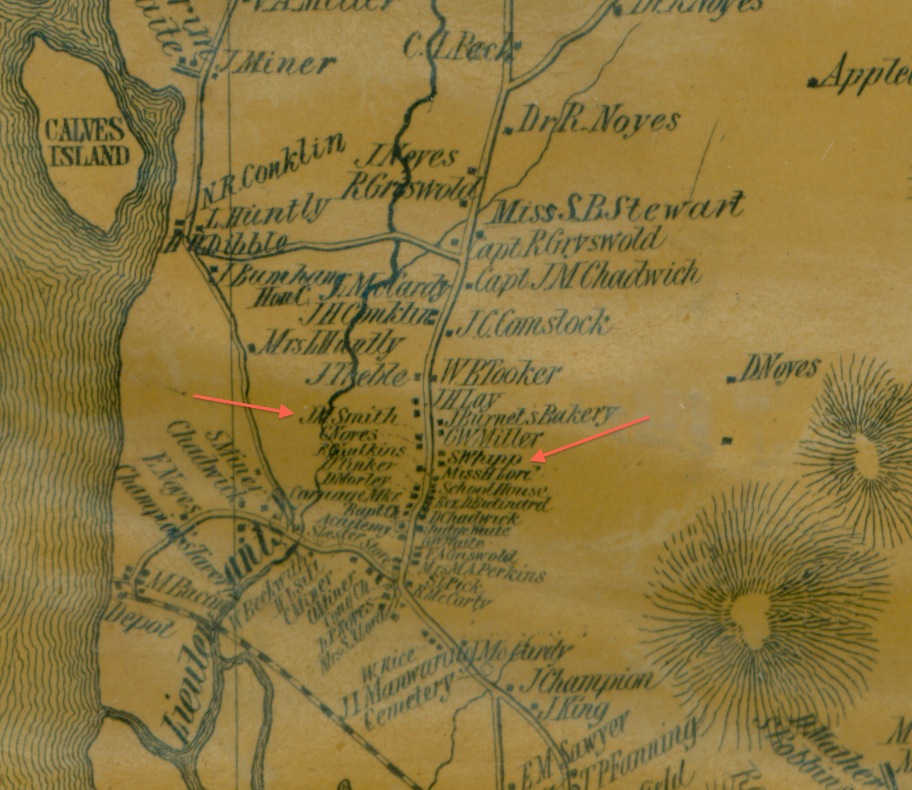

Diagonally across the street from her home, which became known as the Justin Smith house, another colonial-era dwelling served for many years as Simon Whipp’s (1800–1877) tailor shop. Originally built at the foot of Lyme Street across from the town green in about 1768 and later moved, the Whipp house had been the kitchen ell of a much larger three-story gambrel-roofed mansion built in 1784 by the town’s wealthiest merchant Samuel Mather, Jr., (1745–1809).[3]

Town of Old Lyme, ca. 1855. LHSA/FGM

Such antique homes, along with Old Lyme’s natural landscape, beckoned to metropolitan artists in the early 20th century, but the town’s picturesque main street was not always a scenic destination. Discovering the earlier owners of Matilda Browne’s historic house lets us trace the town’s evolution from a prosperous center for trade and shipbuilding to a celebrated art colony.

Early Glimpses of the Town Street

When Samuel Mather, Jr., age 39, built Lyme’s largest dwelling in 1784, he sold to Nathan Tinker (1759–1833), age 24, the house that Matilda Browne would purchase more than a century later. The 20-acre “lot of land & meadow” already included a “dwelling house, barn & shop that is standing and being on said land.” Whether Mr. Mather had ever occupied the house is not known, and more likely he acquired it as an investment. Already successful in the West Indies trade, he was part-owner of two coastal trading vessels and had acquired several other tracts of land in Lyme as well as warehouses and wharves along the Lieutenant River.[4] The census count in 1790 shows that Samuel Mather owned four slaves.

Samuel Mather, Jr., house, ca. 1885. LHSA/FGM

Before purchasing property along “the highway or Town Street” and marrying Sarah Gee (1765–1788) in 1784, Nathan Tinker had served in the Revolutionary War. Later sources identify him as a “Revolutionary soldier and pensioner” and list him in the 10th Connecticut Regiment commanded by Lyme native Col. Samuel Holden Parsons (1737–1789). A pension record in 1833 identifies Nathan Tinker as a “privateer.” He may have previously served on one of the armed merchant vessels outfitted by Samuel Mather, Jr., or by his cousin Sylvanus Tinker (1768–1820), but in August 1776 he engaged in fierce fighting against British troops on Long Island, then joined the stream of sick and wounded, including 25 from Col. John Tyler’s (1764–1840) company, sent to a military hospital in Stamford. Discharged in Stamford in November 1776, Nathan Tinker, age 17, almost certainly [5]returned home to Lyme, where his grandmother Alice Tinker Measure (1629–1714) a century earlier had settled with William Measure (1629–1688), the town’s first schoolmaster.

General George Washington giving the signal to retreat at the Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (148-GW-l74)

Four years after Nathan Tinker’s marriage, his wife Sarah Tinker died from complications of childbirth. By then he had two children, and in 1790 after he married Lucy Smith (1769–1826), he sold his Town Street property to Joseph Smith (1767–1799), who was born and raised in Groton. Whether Joseph Smith, whose father was the first deacon in Groton’s Baptist church, was related to Nathan Tinker’s second wife is not known. After 1790 the house that Matilda Browne would later purchase changed owners multiple times.

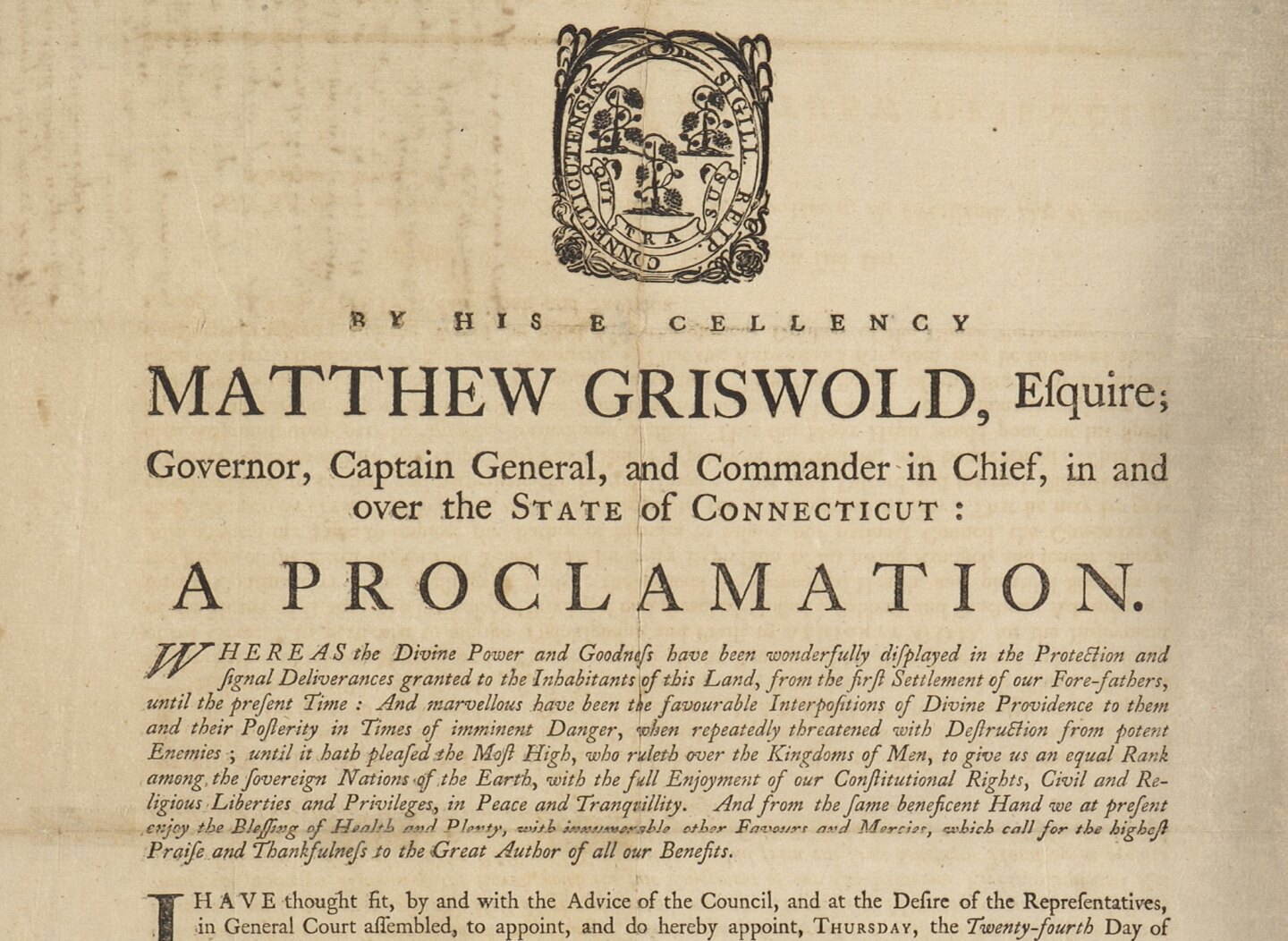

When Joseph Smith died, his brother Charles Smith (1775–1840) purchased the property in 1800 and the next year married into a prominent Lyme family. Lois Parsons Smith (1779–1819), then 22, was the great granddaughter of Rev. Jonathan Parsons (1705–1776), Lyme’s second minister, who had infused church members with evangelical fervor during the tumultuous years of the Great Awakening. Her grandfather Col. Marshfield Parsons (1733–1813) had repeatedly represented Lyme in the General Assembly and had signed, with Samuel Mather, Jr., the letter carried by an express rider conveying news of the shots fired in Lexington in April 1776 that launched the Revolutionary War. Col. Marshfield Parsons, a high-ranking officer in Connecticut’s 3rd Regiment,[6] had turned his father’s parsonage into an inn. Parsons Tavern became a gathering place for those from Lyme like Rev. Stephen Johnson (1724–1786) who urged opposition to British colonial rule.

Charles H. Ludington home, formerly Parsons Tavern, ca. 1890. LHSA/FGM

Matilda Browne’s House during the War of 1812

Trained by his father in harness and saddle making, Charles Smith likely practiced his trade in the shop beside his Town Street dwelling house, but he also prospered in shipping and mercantile trade before the War of 1812.[7] When he served as Lyme’s Justice of the Peace, he became known as “Charles Smith, Esq.,” and it may have been during his ownership that the addition of a kitchen ell and gambrel roof expanded the living space of what had originally been a one-and-a-half-story house with a peaked roof. The original attic would have served for storage and children’s sleeping space until the gambrel roof with two gabled windows created upstairs bedrooms with light, ventilation, and standing head room. By 1815 when the second war with Britain ended, Charles and Lois Smith had five children.

Worn shoes concealed in eaves of Lyme Street house owned by Matilda Browne, 2017

Almost two centuries later two pairs of worn shoes were discovered beneath the eaves of the original attic, most likely placed there when the gambrel roof was added. Concealing old shoes behind the walls of colonial homes was thought to bring good luck, and while the slit-front shoes cannot yet be dated, they may prove to have been worn by Charles and Lois Smith.[8]

After Lois Smith died in 1819 at age 40, her husband sold his Town Street home to his brother Simon Smith (1762–1848). By then the property, which had access to the Lieutenant River, included a store, or storehouse, among its outbuildings. In 1821 Charles Smith married his wife’s half sister Phebe Parsons (1790–?), and by 1828 they had moved to New York state, like many other Lyme residents who sought land and commercial opportunity in “the west” after the Erie Canal opened in 1825.

The Town Street had changed during the four decades since a wealthy Lyme merchant sold a small peaked-roof dwelling house with barn and shop to a Revolutionary soldier and pensioner. The elegant fourth meetinghouse with its soaring spire, intended to rival in design any meetinghouse east of the Connecticut River,[9] had been completed alongside the town green in 1817, and its architect Samuel Belcher (1779–1849) also built two mansion houses for the Noyes family a mile north along the main highway later called Lyme Street. One would become a girls’ school and then a boardinghouse where Florence Griswold after 1900 welcomed impressionist artists like Matilda Browne.

Florence Griswold House, ca. 1885. LHSA/FGM

Next: Matilda Browne’s Historic Lyme Street House, Part II—After the Epidemic

[1] Special thanks to Brad and Gerri Sweet, who meticulously renovated the home previously owned by Matilda Browne, now 54 Lyme Street, and to Amy Kurtz Lansing for information about the artist. Old Lyme Land Records (OLLR) 10:307; Susan G. Larkin, Matilda Browne: Idylls of Farm and Garden (Old Lyme: Florence Griswold Museum, 2017).

[2]OLLR 5:426, 457.

[3]OLLR 7:561; Susan Hollingsworth Ely and Margaret Wellington Parsons, The Parsonage (Old Lyme, 1983), pp. 40-42.

[4]Lyme Land Records (LLR) 16:341; Ely and Parsons, pp. 13, ff.

[5]Dr. Turner to General Spencer, Stamford, November 30, 1776, in Peter Force, American Archives. . .: A Documentary History (Washington, 1853), p. 939; Thomas A. Stevens, “Lyme: A Town Inexorably Linked to the Sea,” (Deep River, 1959), p. 14; Henry P. Johnston, ed., Record of Service of Connecticut Men in the War of the Revolution (Hartford, 1889), pp. 99-100.

[6] Bruce P. Stark, Lyme, Connecticut: From Founding to Independence (Old Lyme, 1976), p. 45.

[7]Henry Allen Smith, Descendants of the Rev. Nehemiah Smith of New London County, Conn. (Albany, 1889), pp. 93, 131.

[8]Brad Sweet to Carolyn Wakeman, May 2017; Mr. Sweet discovered the shoes during his renovation. June Swann, “Shoes Concealed in Buildings,” Costume no. 30 (1996), pp. 56-69.

[9] Susan Hollingsworth Ely, Margaret Wellington Parsons, Willis H. Umberger, History of the Congregational Church of Old Lyme, Connecticut (Old Lyme, 1995), p. 85.