by Charles Beal

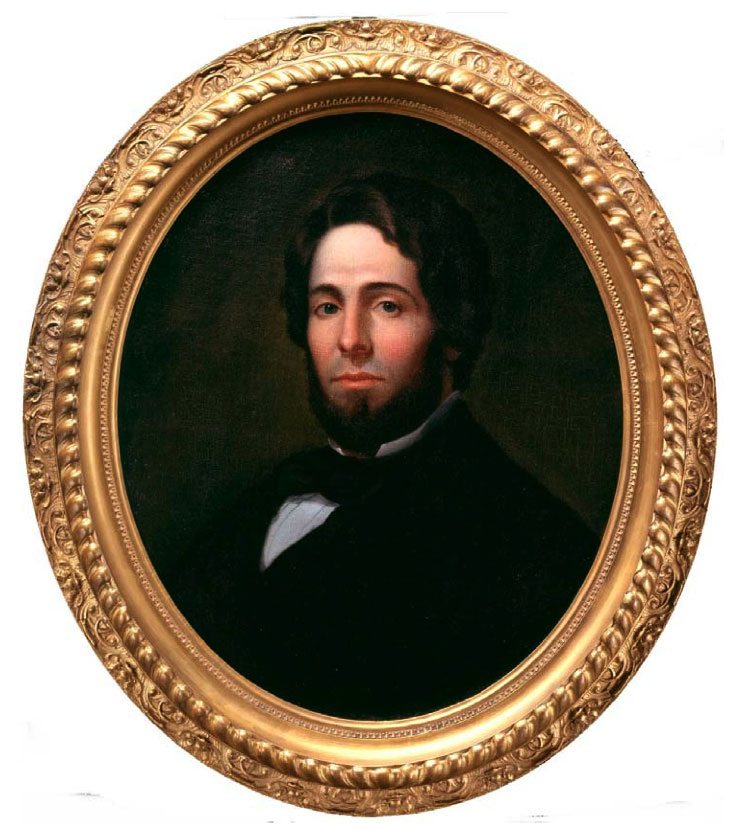

Feature Photo (above): Thomas Coke Ruckle, Captain Robert Harper Griswold, 1840. Watercolor on paper. FGM. Gift of Dr. Matthew Griswold.

Captain Robert Griswold is remembered as a respected sea captain who owned one of the grandest homes in Old Lyme and whose daughter Florence was the inspiration for the thriving museum that today bears her name. Family letters and the journal of a famous American novelist shed light on his character and his years at sea.

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Governor Griswold’s House, 1876. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Governor Griswold’s House, 1876. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

Early Years

Robert Harper Griswold, born in Lyme, was the ninth of Governor Roger Griswold’s (1762–1812) ten children. His father’s political career required long absences from home, and his mother Fanny Rogers Griswold (1767–1863) provided much of the children’s guidance and supervised their early education. Robert almost certainly attended the Black Hall district school near his home.

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Approach to Black Hall, 1876.Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Approach to Black Hall, 1876.Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

Like many members of his family, he became a mariner at an early age. By 1829, he was serving as a second mate and in 1831, when he was just 25, he was listed as the captain of the packet ship Samuel Robertson for a voyage from London to New York.[1] For the next 24 years, he sailed the Atlantic on packet ships of the Black X Line, including the Sovereign (1834–1835), Toronto (1835–1844), Northumberland (1844–1849), Southampton (1849–1850) and Ocean Queen (1850–1854).[2]

At age 34 Captain Griswold in 1840 married Helen Powers (1820–1898) from Guilford, who was then 20, and the following year he had sufficient financial means to purchase the former William Noyes estate on Lyme Street. During her husband’s long years at sea, Helen Griswold would have primary responsibility for maintaining the household and raising their four children, Louise (1842–1896), Helen Adele (1845–1913), Robert Harper (1847–1864), and Florence Ann (1850–1937).

Helen Powers Griswold

Southampton Passage

Insight into the life and times of Captain Griswold is provided by a journal kept by novelist Herman Melville (1819–1891) during a voyage from New York to London in 1849 on the ship Southampton.[3] A typical packet ship of that time, it had a gross weight of 1299 tons and carried as many as 350 passengers. Usually about 30 passengers traveled comfortably in cabin class and the balance in steerage.[4]

Asa Twitchell, Herman Melville, ca. 1847. Courtesy Berkshire Athenaeum.

Asa Twitchell, Herman Melville, ca. 1847. Courtesy Berkshire Athenaeum.

According to Melville’s journal, which had entries for every day of the voyage and beyond, the ship sailed on October 11, 1849. After a difficult start, with heavy seas and many ill passengers, the ship sailed to London in generally favorable weather. The total voyage took 26 days.

Life on the ship was agreeable for the cabin passengers who enjoyed good food, fine wine, and entertainment in the men’s and lady’s saloons. Melville spent many evenings engaged in intellectual discussions about philosophy and politics but had very little interaction with those traveling in the crowded conditions below the main deck. His journal includes multiple references to Captain Griswold.

Upon boarding the ship Melville was pleased with his single stateroom: “But to my great delight, the promise that the Captain had given me at an early day, he now made good; & I find my self in the undevided occupancy of a large state-room. It is as big almost as my own room at home; it has a spacious birth, a large wash-stand, a sofa, glass &c &c. I am the only person on board who is thus honored with a room to himself.”

Samuel Walters, The Northumberland, 1847. FGM. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William E. S. Griswold, Jr.

Samuel Walters, The Northumberland, 1847. FGM. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William E. S. Griswold, Jr.

When a steerage passenger suddenly jumped overboard after two days at sea and refused to be saved, Melville wrote: “The Captain said that this was the fourth or fifth instance he had known of people jumping overboard. He told a story of a man who did so, with his wife on deck at the time. As they were trying to save him, the wife said it was no use; & when he was drowned, she said ‘there were plenty more men to be had.’ Amiable creature!—“

Ten days later on October 23, 1849, Melville described Captain Griswold’s interaction with the cabin passengers: “On gaining the deck this morning was delighted to find a fair wind. . . . Every one in high spirits. Captain told a rum story about a short skipper and a long mate in a little brig, & throwing overboard the barrels of beef & turpentine &c. Captain Griswold joined the cabin passengers again on October 29 for their evening entertainment. “Wet & foggy,” Melville wrote, “but a fair fresh breeze-–12 knots an hour. Some of the passengers sick again. In the afternoon tried to create some amusement by arraigning Adler before the Captain on a criminal charge. In the evening put the Captain in the Chair, & argued the question ‘which was best, a monarchy or a republic?’–Had some good sport during the debate–the Englishmen wouldn’t take part in it tho’.”

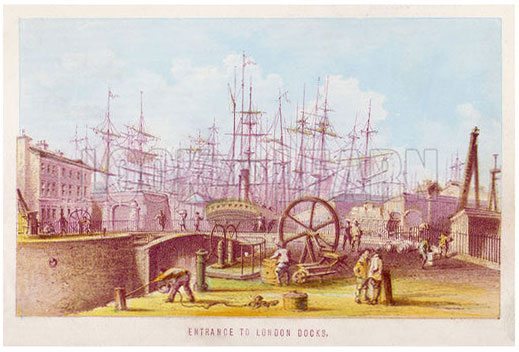

Entrance to London Docks, ca. 1850

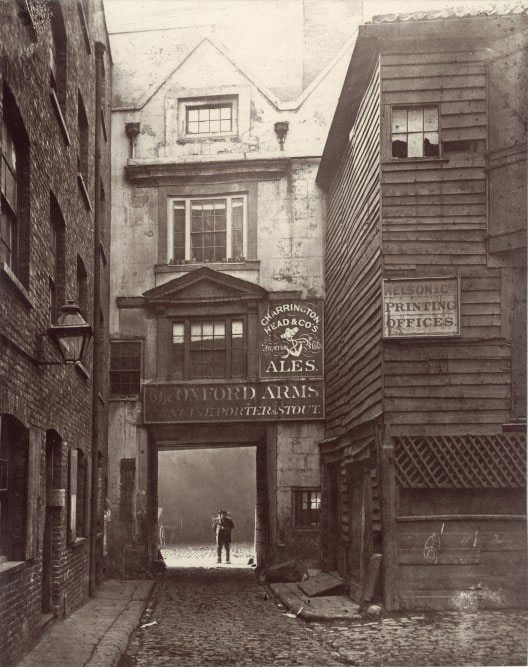

Melville never mentions his initial opinion of Captain Griswold, but clearly his assessment changed during the voyage. On November 1 he wrote: “The Captain is a very intelligent & gentlemanly man–converses well & understands himself. I never was more deceived in a person than I was in him.” Their social relationship continued after the Southampton docked in London, and on November 12 Melville described a lavish meal and an “exceedingly diverting” pub visit: “Had a noble dinner of turtle soup, pheasant &c with glorious wine. At 10 o’clock, left with the Captain & the rest of the company (Doctor, Adler, Mulligan, McCurdy, ‘Stetson’) for the ‘Judge & Jury’ Bow Street. Exceedingly diverting but not superlatively moral.”

The Oxford Arms, a London inn, ca. 1850

The Oxford Arms, a London inn, ca. 1850

Melville later gave Captain Griswold a book as an expression of gratitude and received a note of appreciation in return. Their contact ended when Melville went on to travel in Europe, and Captain Griswold left London on the Southampton in late November or early December 1849 and headed for New York.

For the winter passage, the ship carried only 78 passengers, 18 in the cabin and 60 in steerage. The passengers, crew, and captain spent Christmas Day 1849 at sea, and the ship arrived in New York on January 9, 1850.[5] That was Captain Griswold’s final voyage on the Southampton.

His next crossing was on the new packet ship Ocean Queen, which left New York for London in April 1850. In early May when the ship was off the southern coast of England, the cabin passengers composed a letter to the Captain thanking him and the officers for their “courteous and gentlemanly deportment” and for “the skill they have displayed in the navigation of the ship through an unusually stormy passage.”[6]

Years at Sea

On three occasions Helen joined her husband on his transatlantic voyages, first by herself and later with her children. When she sailed with Robert in 1841 shortly after their marriage, she wrote about sight-seeing trips in London as well as the plays and concerts they attended. Six years later she traveled with him again, as Robert wrote in 1847: “I sail tomorrow and my wife and eldest girl go out with me.” In 1851 Helen’s mother Julia Powers wrote about Helen and the three oldest children on another crossing.[7]

Captain Griswold’s schedule caused him to be away from home for many holidays and family occasions, including the birth of their daughter on Christmas Day 1850. He learned of Florence Ann’s arrival from his mother: “I have the pleasure to inform you that Christmas morning about three o clock Helen was confined with a fine plump daughter–She has been very miserable after you left indeed I never saw her fret about your absence so much as this time.” Describing the baby, Robert’s mother observed: “the child is very quiet, has black hair and eyes and fine features and she [Helen] is rejoiced that it is a daughter.”[8]

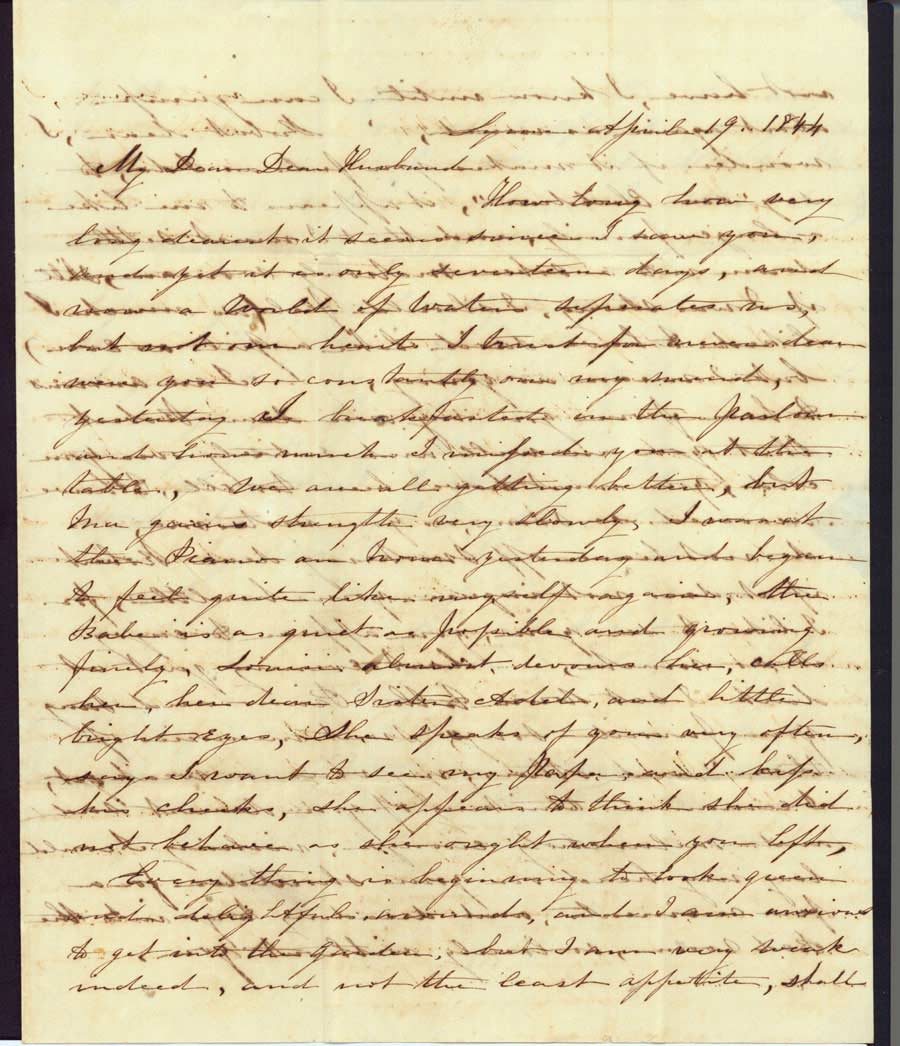

Helen Powers Griswold letter to her husband, 1844. LHSA

Helen Powers Griswold letter to her husband, 1844. LHSA

The time apart and the dangers the captain faced took a toll on his family. Helen repeatedly “fretted” about her husband’s absence, and in 1844 she wrote: “My Dear Dear Husband, How long how very long dearest it seems since I saw you, and yet it is only seventeen days, and now a world of waters separates us. . . .” The following year she again expressed her longing: ”O Robert I never wanted so much to see you and be with you as now, it is hard that we are obliged to be separated so often and so long, you are always in my thoughts, waking or sleeping, and I am always anxious until I hear from you, do write me long letters dear Robert.” In 1852, apparently wearying of command, Robert echoed his wife’s sentiments: “Oh how I dreaded the voyage and leaving you and all I left behind. How I hate this life of mine. Tis misery.”[9]

During the years that Captain Griswold sailed the Ocean Queen, the number of immigrants awaiting transportation to the United States dramatically increased, and the number of passengers crossing from London on the Ocean Queen grew from an average of 280 in 1850 to a peak of over 600 when the ship reached New York on October 16, 1854.[10] After that voyage Captain Griswold passed the command to Captain A. Spencer who made three trips across the Atlantic in 1855.

Samuel Walters, The Ocean Queen, 1851, FGM. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. E. S. Griswold, Jr.

Samuel Walters, The Ocean Queen, 1851, FGM. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. E. S. Griswold, Jr.

On its next voyage, under the command of Captain W. B. Smith, the Ocean Queen went down. Ice floes were reported farther south in the North Atlantic than usual during the harsh winter of 1856, and the ship was last seen on February 15 off the Isle of Wight. All 123 people on board, including 20 German immigrants, were lost at sea.[11]

Retirement in Lyme

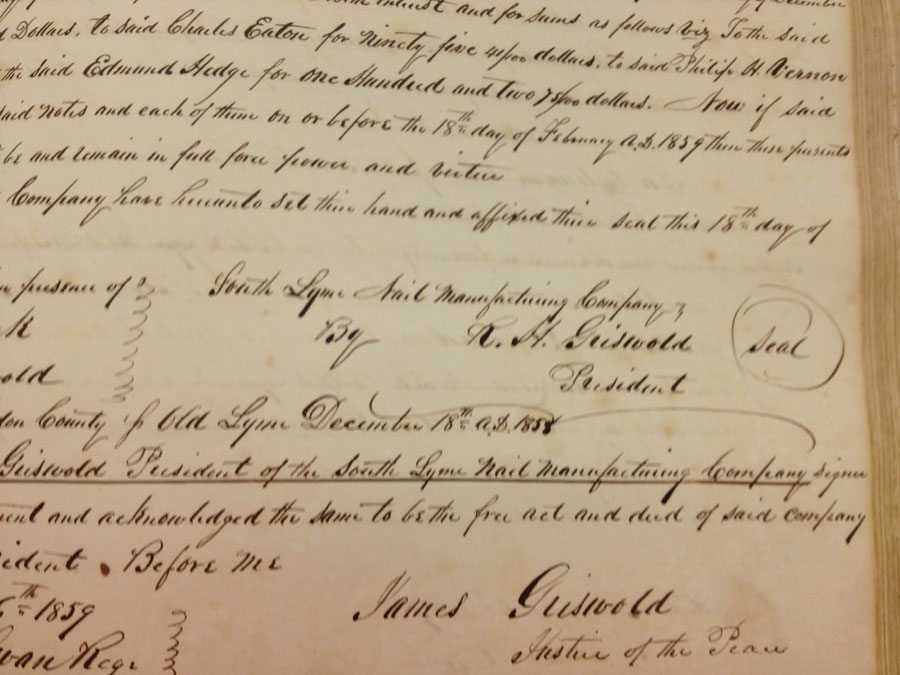

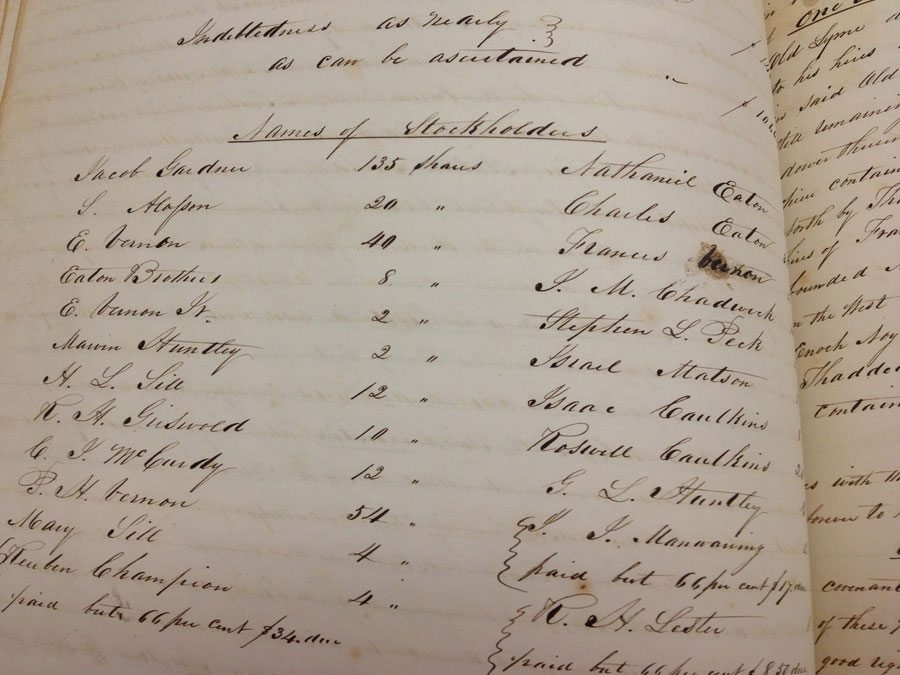

After his retirement as a packet ship captain at age 49, Capt. Griswold joined a group of other local investors in a start-up business called the South Lyme Nail Manufacturing Company. He purchased only a modest number of shares, but when the business was sold in 1858 he served as president. A year later he bought a small blacksmith shop, dam, and water works near the factory site.[12]

South Lyme Nail Manufacturing Company deed of sale, 1858, signed by R. H. Griswold, president

South Lyme Nail Manufacturing Company deed of sale, 1858, signed by R. H. Griswold, president

South Lyme Nail Manufacturing Company shareholders, 1855

South Lyme Nail Manufacturing Company shareholders, 1855

Robert Griswold had accumulated significant wealth by 1860. The census that year records the combined value of his real and personal property as $60,000 and counts twenty people in his household. They included his wife and four children, his mother who had been legally blind for six years, three servants, a farm laborer, and what appears to be a large tenant family. Perhaps Henry W. Haynes, a 44-year old carpenter, together with his wife and seven children occupied the “brick store” that Capt. Griswold acquired when he purchased the Noyes estate.

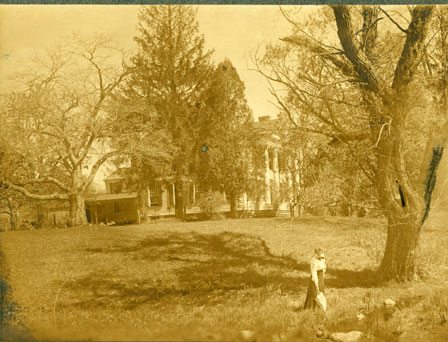

Florence Griswold House, c. 1905

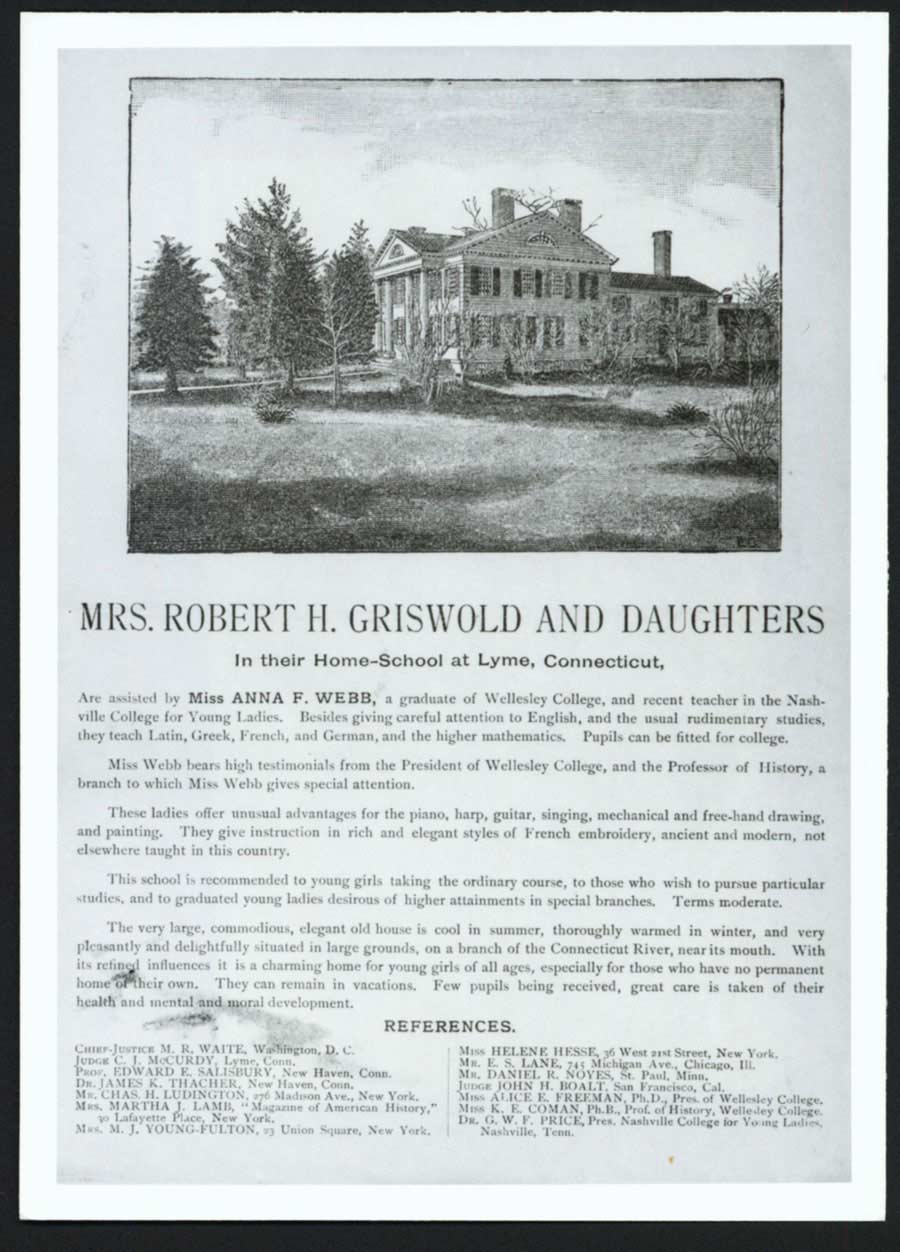

A decade later the census in 1870 valued his assets at $48,000. Both his mother and his son Robert had died, the Haynes family had left, and the household consisted of Helen, their three unmarried daughters who had no occupations, and one servant. Within a few years the family’s financial circumstances must have changed. In 1878 Helen Griswold and her daughters, apparently needing income, established a girls’ school in their home.

Advertisement for Griswold Home School, LHSA.

Advertisement for Griswold Home School, LHSA.

The 1880 census omits property values but shows that Capt. Griswold no longer had a servant and that his three daughters all had occupations. Louise was a music teacher, Helen Adele an artist, and Florence a school teacher. Two years later when their father died, his once substantial resources had disappeared. He left to his wife and daughters only the house, a few farm animals, and minimal financial assets.[13]

[1] The Norwich Mercury, July 30, 1831. Cited in “New York Line of Packets,” Immigrant Ships Transcribers’ Guild, Maritime Newspaper Articles, 1830.

[2] A brief account of the Griswold Black X Line appears in Kenneth J. Blume, Historical Dictionary of the U. S. Maritime Industry (Plymouth 2012), pp. 204-205.

[3] Herman Melville, Journal of a Voyage from New York to London 1849. http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~ehrlich/361/melville_journals.html

[4] Passenger List when the Southampton arrived at New York on May 11, 1850, Captain E. E. Morgan, is available here

[5] Passenger List when the Southampton arrived at New York, January 9, 1850, Captain R. H. Griswold, is available here

[6] Letter from cabin passengers on the ship Ocean Queen to Captain Robert Griswold, May 9, 1850, Photocopy, Griswold Collection, LHSA.

[7] Helen Powers Griswold to Caroline, January 23, 1841, photocopy, Lane Collection, LHSA; Robert Griswold to E[benezer] Lane, his brother-in-law, May 10, 1847, photocopy, Lane Collection, LHSA; Julia Powers to Helen Powers, April-July, 1851, photocopy, Lane Collection, LHSA.

[8] Fanny Griswold to Captain Robert Griswold, December 28, 1850, photocopy, Griswold Collection, LHSA.

[9]Helen Griswold to Captain Robert Griswold, January 29, 1845, Griswold Collection, LHSA; Captain Robert Griswold to Helen Griswold, March 10, 1852, Griswold Collection, LHSA.

[10] Passenger List when the Ocean Queen arrived at New York, October 16, 1854, Captain R. H. Griswold, is available here

[11] The New York Times reported the loss of the Ocean Queen on July 12, 1856.

[12] See Old Lyme Land Records (OLLR) 1:18 (December 10, 1855), Formation of the South Lyme Nail Factory, for Robert Griswold’s purchase of 10 of the original 400 shares offered at $25 per share. See OLLR 1:227 (December 18, 1858) for South Lyme Nail Factory’s sale to Pacific Iron Works. See OLLR 1:270 (October 21, 1859) for Robert Griswold’s purchase from George A. Smith of a blacksmith shop, dam, and waterworks.

[13] Old Lyme Probate Records, Robert H. Griswold Estate Inventory (January 9, 1911), Vol. 6, page 81.