By Patty Devoe

Featured Image: Susan Platt Hubbard as a young woman, Platt Hubbard Collection, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Seventy-two years passed between the first women’s rights convention, held at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, and the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution that granted suffrage to women in 1920. The battle was hard fought as many women opposed the cause, a position somewhat hard to understand in the 21st century. As we approach the 100-year anniversary of the Amendment’s ratification, it is worth delving into Old Lyme’s anti-suffrage movement to see how much has changed, as women’s rights are still very much in the crucible of American politics.

One Old Lyme resident who passionately felt that women did not need the right to vote was Susan Platt Hubbard (1865-1952). Born into an affluent mercantile family in Columbus, Ohio, she was a niece of President Rutherford B. Hayes, related to Charles Adams Platt (artist and architect of the Lyme Art Association gallery), and the mother of landscape artist Platt Hubbard (1889-1946). Educated by private tutors and a graduate of the prestigious Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, Susan Platt married businessman Hermon Milton Hubbard in 1886 and over the next thirty years participated actively in social and civic organizations in Columbus. Wealthy, well-educated, well-spoken, well-connected, and successful at influencing change outside the male-dominated political system, she was elected president of the Ohio State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage in 1911.

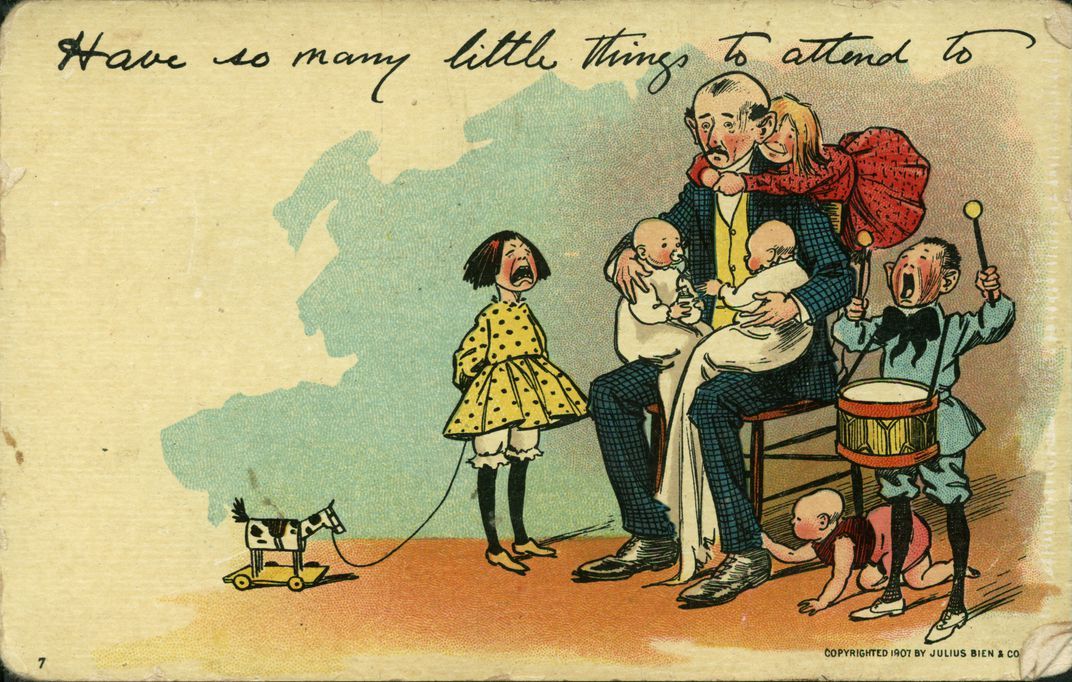

Anti-Suffrage Postcard,Palczewski, Catherine H. Postcard Archive. University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, IA.

The next year, in an address published in The Ohio Journal of Commerce, Mrs. Hubbard vigorously rebutted suffragist arguments. Her opposition hinged largely on the premise that: “It is by educating public opinion rather than by voting that social and political reforms have been brought about.” Although “individualism is the cry of the age,” she declared, “the individualism of woman in these modern days is a threat to the family.”[1]Confident in her views, she ardently denounced those who argued that voting was an inherent right, that women were physically and intellectually as capable as men to vote, and that without the right to vote women were being taxed without representation.

100,000 women marched in support of suffrage in Cleveland in 1914, Plain Dealer Historical Photograph Collection

Five years later the tide of public opinion had shifted, and the suffragists’ arguments gathered increasing support. After women in 1917 had gained the right to vote in nineteen states, as well as in municipal elections in Columbus, Susan Platt Hubbard reluctantly closed her Ohio anti-suffrage office. In a letter to Walter Magee (1874-1952), the close friend of her son Platt Hubbard in Old Lyme, she wrote: “With no excuse now not to do things I ought to do, I have to clean up our pitiful little anti-suffrage office, a most disagreeable task.”[2] That same year Mrs. Hubbard carried her political ideas and her assertive style to the small Connecticut town where her son had joined the colony of artists who gathered there after 1900.

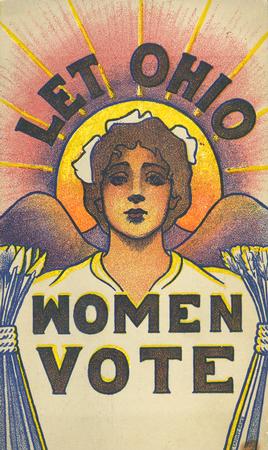

Postcard produced by the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association and mailed from Columbus in 1915, The Ohio History Connection

Concerns about Hermon Hubbard’s health following a nervous breakdown in 1917[3] contributed to the Hubbards’ decision to settle permanently in Old Lyme. After initially renting the charming Garden Roads cottage on Ferry Road, they bought acreage along the Connecticut River in 1919 and the next year built a house they named “The Cedars,” which artist and ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson would purchase after Mrs. Hubbard’s death in 1952.

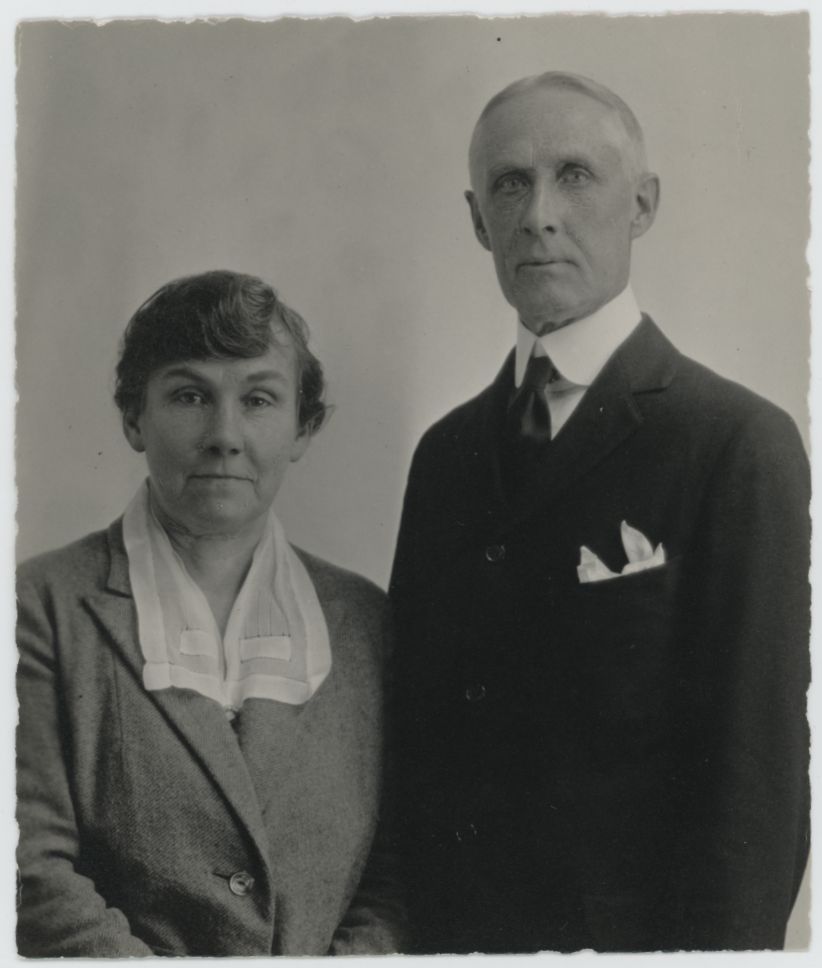

Susan Platt Hubbard and her husband Hermon M. Hubbard, Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

The Old Lyme Society Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage had enrolled many of the town’s prominent women after its founding in 1912. Under its first chairwoman Elizabeth P. Ely, the group attracted local members, including art colony founder Florence Griswold, through genteel and traditional activities. “A tea was given at the Grange Hall on the afternoon of April 29th, 1914, for the benefit of this association. There was a good attendance and the entertainment was in every respect a success. The musical selections on the Victrola, which Miss [Anna] Huntington had kindly loaned for the occasion, were a pleasant feature of the afternoon.”[4] Miss Huntington had also contributed to the Society in 1914 a subscription to The Woman’s Protest, a nationally circulating publication promoting the anti-suffrage movement that frequently noted Mrs. Hubbard’s contributions to the cause in Ohio.

The Women’s Protest, 1912. National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage

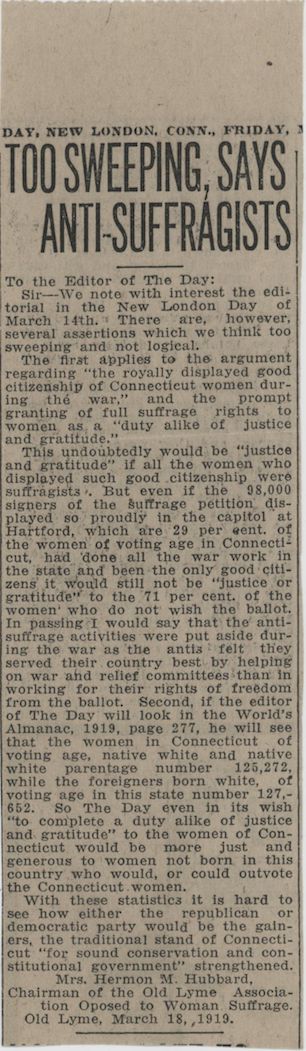

When Miss Ely resigned in 1919, the Old Lyme organization boasted 135 members. “After 7 years of most conscientious administration,” the Society’s minutes reported, “Miss Ely feels she can no longer continue as chairman and Mrs. Hubbard has kindly consented to take the office. I think we are all familiar with her splendid work as state president of the Ohio Association and we extend to her a most cordial welcome.”[5] Susan Platt Hubbard’s approach, as Miss Ely’s successor, was more strident and confrontational. In March 1919, the same month she was elected chairperson, she roused anti-immigrant sentiments in a letter to The New London Day questioning who deserved the right to vote. “With weightier problems before the voters of this country to decide than any time since the Civil War, is it wise, is it best,” she queried, “to increase the electorate and double the number of voters who have not been born under our flag and therefore do not feel the same responsibility towards upholding America and American institutions. We antis, 71 percent of the women of Connecticut, say No.”[6] The next month she raised the threat of socialism. If women had the vote forced upon them, “the whole country will be in danger of Socialism, Bolshevism, and anarchy,” she declared, as “the working man is always dissatisfied and would be only too glad with the help of his wife to overthrow the government.” [7] Mrs. Hubbard also insisted that women did not have the intellectual capacity to vote. “When the women who wish to vote cannot correctly count up a list of those who wish to vote, . . . how can they intelligently deal with a town, state, or national budget?”[8]

Katharine Ludington (1869-1953), also a wealthy and socially prominent Old Lyme resident and a graduate of Miss Porter’s School, led the fight in Connecticut to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1919. But while she insisted that Governor Marcus H. Holcomb call a special session of the state legislature to ratify the Amendment, Susan Platt Hubbard applauded his refusal. In a letter to The Hartford Courant and reprinted in The Woman Patriot, she declared that “the greater majority of the women of Connecticut do not want the responsibility of the vote”[9] and lavishly praised the governor for respecting the rule of the majority.

A letter to the editor of The New London Day from Susan Platt Hubbard, March 1919, Organizations, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Connecticut ratified the 19th Amendment a year later in September 1920, but Susan Platt Hubbard never gave in, and her views about suffrage and about women’s emergence in public life did not change. In a letter to her son Platt Hubbard in April 1921[10], Walter Magee mentioned the possible diplomatic posting of Ohio suffrage leader Lucille Atcherson (1894-1986), against whom Mrs. Hubbard had argued, and enclosed a clipping from The Columbus Dispatch. The article might “amuse you and your mother,” Magee remarked wryly. “The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, running true to form, has taken up the cudgels against the appointment of Miss Lucile Atcherson of Columbus to a position in the diplomatic service,” the newspaper columnist reported. “Most persons had supposed that the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage would cease to function when suffrage became a fact, but it appears that the association is being kept very much alive and that one of its purposes is to ‘knock’ whenever it is suggested that a woman be appointed to office.” Despite persistent anti-suffrage sentiments, like those Susan Platt Hubbard urgently championed, Lucile Atcherson became in 1923 the first woman to serve as a diplomatic officer in the U.S. Foreign Service.

A closer look at the early 20th century anti-suffrage movement in Old Lyme, and at the words and actions of Susan Platt Hubbard, helps to illuminate political concerns today about women’s rights, immigration, patriotism, nationalism, socialism, corruption, protest, majority rule, and minority rights. What’s old is new again, and there is quite a lot to think about while reviewing the struggle that brought women the right to vote just a century ago.

[1] Mrs. Hermon Hubbard, “Power Without Responsibility – The Certain Consequence of Equal Suffrage,” The Ohio Journal of Commerce, April 13, 1912, p. 228.

[2] Platt Hubbard Collection, LHSA, File Number 150-8.

[3] The Boston Globe, July 5, 1933, p. 13.

[4] Old Lyme Society Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage Notebook, LHSA, Organization Box 1, Folder 8

[5] Handwritten note, Old Lyme Society Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage, LHSA, Organization Box 1, Folder 8.

[6] The New London Day, March 24, 1919.

[7] The New London Day, April 7, 1919.

[8] The New London Day, April 18, 1919.

[9] The Woman Patriot, August 23, 1919, p.2.

[10] Platt Hubbard Collection, LHSA, File Number 150-68.