Portrait of an older white woman with grey, wavy hair covered with white lace. She wears a black dress with a lace collar with a brooch at the center.

by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured image: George Henry Yewell, Phoebe Griffin Noyes [detail]. Courtesy Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library

Not only in 2020 have the ideals of American democracy been sharply contested. Five years before the country plunged into Civil War, the issues debated in the 1856 presidential election campaigns aroused intense passions. In the aftermath of the divisive Kansas-Nebraska Act, freedom and slavery were on the ballot. That law, which allowed the country’s western territories to choose whether as states they would permit slavery, passed in 1854. “The dark clouds gathering over Kansas portend a fearful storm,” Sarah Lord Hyde, age 30, wrote to Harriet “Angie” Lord Burr, then traveling in Europe with her husband Rev. Enoch Fitch Burr.[1]

The Lord sisters, raised in North Lyme, maintained a lively correspondence after they married and lived apart. Conveying the sharp political partisanship of the press as the presidential election neared, Sarah remarked wryly to Angie that one newspaper contributor had even reached “the sage conclusion that ‘the slaves of the south are the happiest and most contented people in the world.’” With bitter sarcasm she added, “what a blessing is the peculiar institution,” then urged, “God give Freedom to triumph in the conflict.”

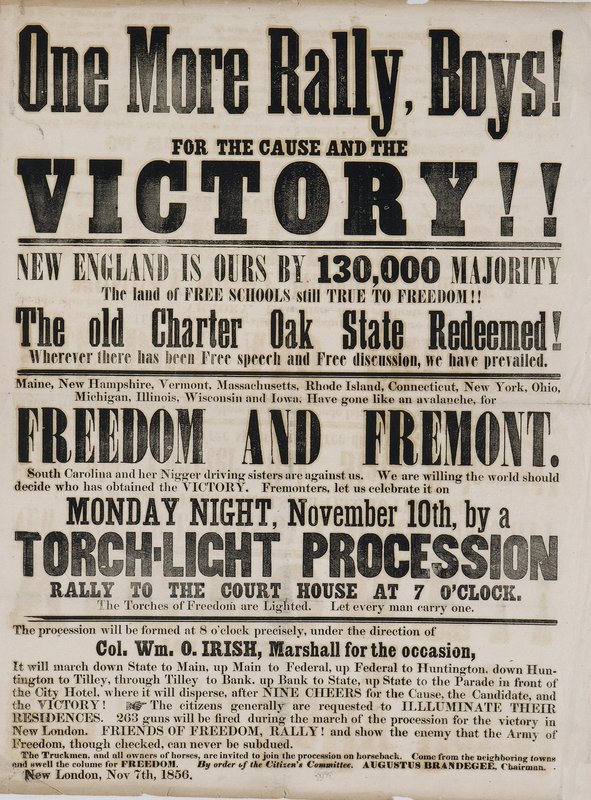

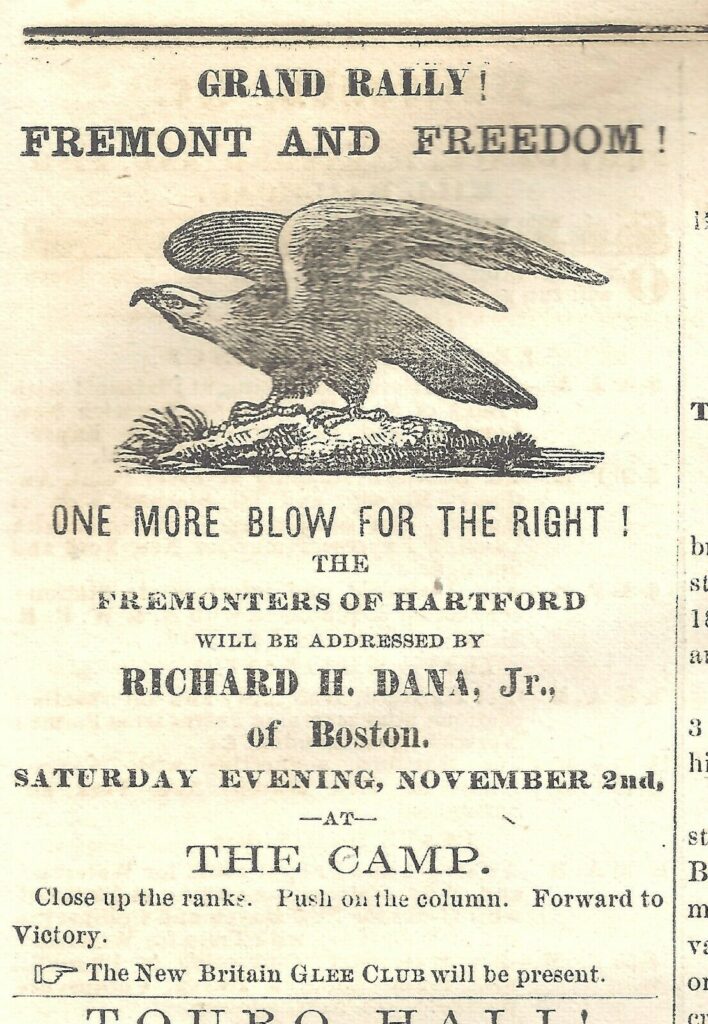

The Republican national convention four months later in July 1856 nominated as its presidential candidate the famous explorer John C. Fremont, who opposed the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850 and pledged to deny the authority of Congress to give any form of legislative assistance to slavery. The Democratic Party’s candidate James Buchanan staunchly supported the westward expansion of slavery and the right of southerners to own slaves. Republicans, urging a stop to the spread of slavery, promoted the slogan “Freedom and Fremont,” and local Fremont clubs called for “Free Speech, Free Press, Free Soil, Free Men, Fremont and Victory.”

Broadside for political rally by Fremont supporters in New London, November 10, 1856. Connecticut Historical Society

In Connecticut, which had abolished slavery only eight years earlier in 1848, Fremont clubs spread across the state, stressing the urgency of the issues at stake. In August 1856 a new Fremont club in Middletown declared that “our country is about to enter into a Presidential campaign involving issues which we believe to be the most momentous presented to the American People since the adoption of the Constitution.” In Old Lyme (then called South Lyme), Katharine Ludington notes in a family memoir, her uncle Charles P. Noyes, age fourteen, formed a Fremont Club that marched through town with banners declaring, “Fremont, Freedom and Free Kansas.” Following the demonstration Judge Charles J. McCurdy, recently Connecticut’s lieutenant governor, prepared a dinner in the town hall for the group called the “Liberty Boys of ’56.”[2]

Poster announcing a rally in Hartford for Fremont and Freedom, The Hartford Evening Press, October 31, 1856

With the issue of “bleeding Kansas” looming over the election, Charles’s mother Phoebe Griffin Noyes, after whom Old Lyme’s public library would later be named, wrote a lively ballad for her students to emphasize the urgency of the issues at stake. Mrs. Noyes had conducted a private-tuition school in her home beside the Congregational Church for twenty years. Calling “the morrow’s great election” the “all-absorbing subject,” she echoed in her poem The Evil Omen the apprehension that Sarah Lord had recently conveyed to her sister:

Sadly the wind was moaning

Among the naked trees

And a sound of coming evil

Seemed to sigh in every breeze.

The ballad contrasts students who stood “For Fremont and for Freedom” with those who failed to “reflect upon the sufferings/ Of the poor unhappy slaves.” While one even wished she had “a blackey/To stand behind her chair,” others “think of bleeding Kansas” and “mourn their country’s shame.” As the poem unfolds, the teacher stands “silent and aghast” to find Buchanan’s name displayed in a poster mounted on the wall, “when all thought his name had perished.” Thrusting the flyer into the stove, she denounces his supporters as “traitors,” but just then a puff of wind suddenly “snatched him from out the grate.” The concluding stanza warns of a Buchanan victory:

The Omen is a bad one—

“Alas,” the lady cries:

For Freedom and for Kansas

My only hope now dies![3]

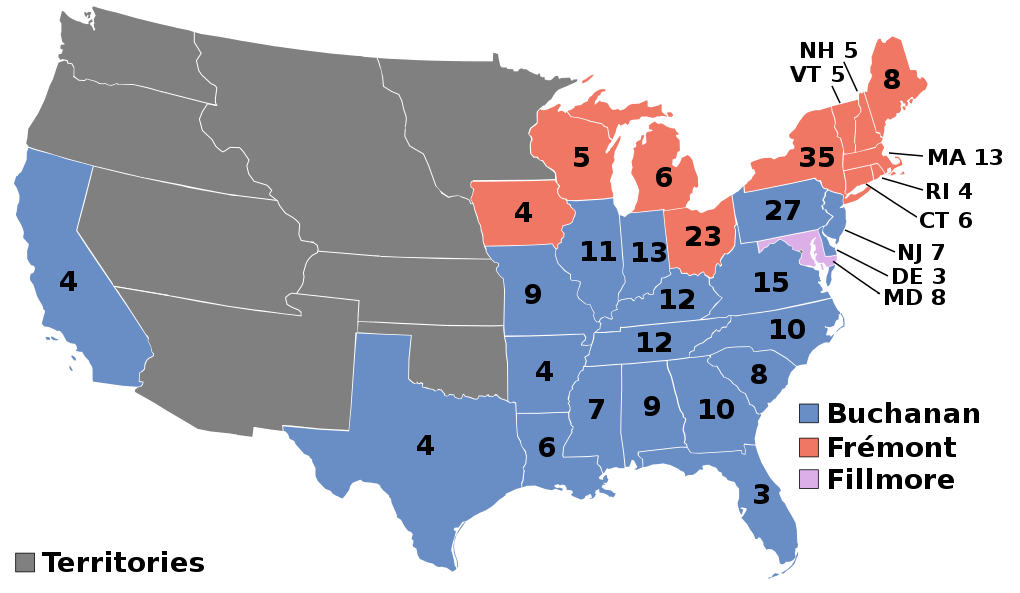

Noyes’s “only hope” was in fact crushed on election day in November 1856 as Buchanan swept the South and became President. Two days after his inauguration on March 4, 1857, the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision concluded that Blacks were not U. S. citizens and opened all American territories to slavery.

Electoral College Votes, 1856 Presidential Election. Wikipedia

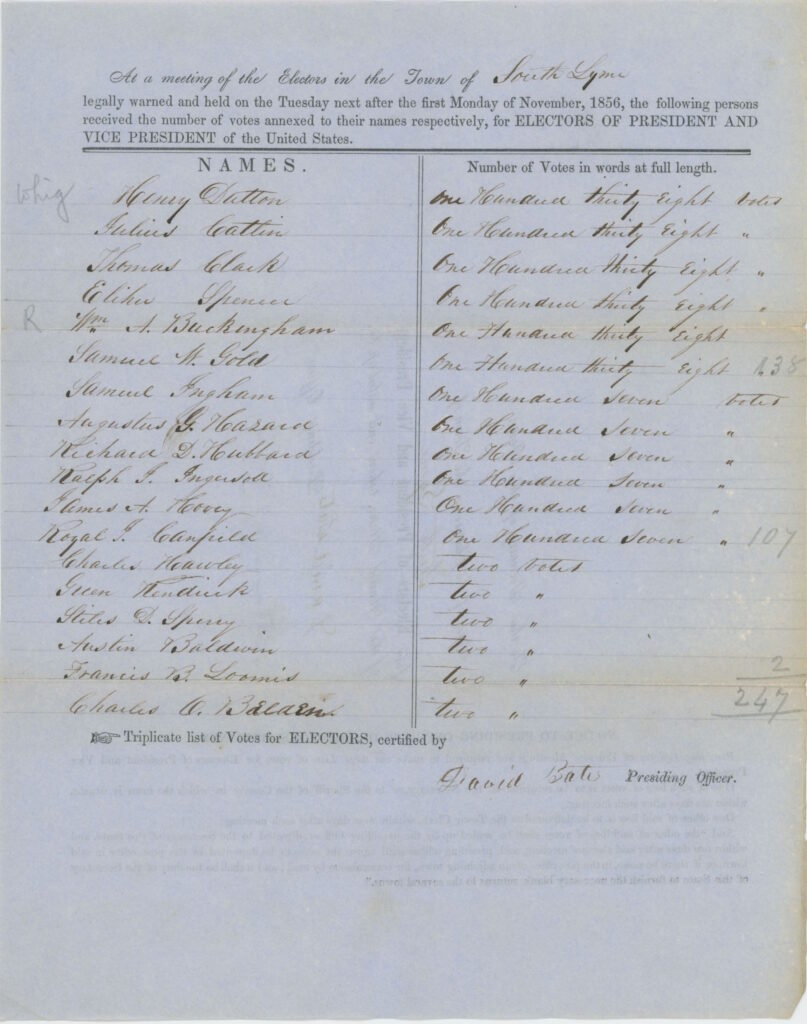

Connecticut, like other northern states, gave its electoral votes to the Republican Party’s candidate John Fremont. A report from Hartford on November 4 shows that not only South Lyme (later Old Lyme) but also Lyme (formerly North Lyme) voted in accordance with the state’s preference.[4] The two communities had been neighboring ecclesiastical parishes in the original town of Lyme for more than a century, but in 1855, as the issue of slavery divided the country, they separated into two legally distinct towns.

Votes of the Election in the Town of South Lyme for Electors of President and Vice President of the United States, taken and sealed up by David Bates, Presiding Officer. Old Lyme Election Results, 1856-9, Folder 1, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

In North Lyme the outcome of the presidential election was considered surprising, as the opinions of James A. Bill, an outspoken sheep farmer and an ardent Democrat, had previously prevailed there. Bill showcased the intensity of his political views in 1855 by naming a son born that year Kansas Nebraska Bill. “The Fremonters” there had to contend against great odds, The Hartford Courant reported, “as well as little Dr. Olds.” The thinly veiled comparison of James Bill to Dr. Edson B. Olds, a staunch Democrat and Buchanan supporter in Ohio, would have been obvious to contemporary readers. “A majority of 43 votes for Fremont,” the Courant noted, “tells its own tale that somebody worked well for Fremont, in this refractory town,” despite “lots of money, freely spent.”[5]

James A. Bill’s house and farm, today’s Ashlawn Farm, on Bill Hill Road, Lyme, Connecticut, ca. 1888. Courtesy Lyme Public Hall

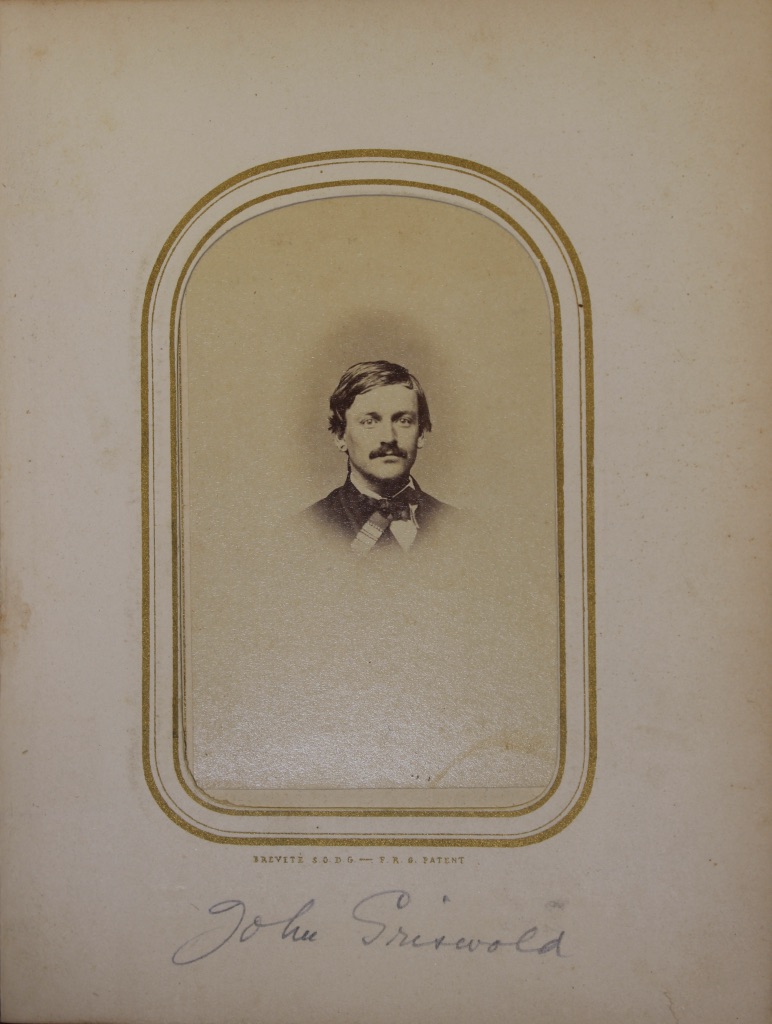

James Buchanan’s presidency lasted only one term but left the country on the brink of civil war. Five months after Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election in November 1860, the deadly conflict termed the War between the States began with shots fired at Fort Sumter. Phoebe Griffin Noyes’s use of the word “traitor” to describe Buchanan and his supporters in 1856 recurs in an impassioned letter that Ellen Perkins Griswold in Old Lyme wrote to her son John Griswold in September 1861. “If ever Traitor deserved the name, it must be given to Buchanan,” declared the politically astute daughter-in-law of Connecticut’s former governor Roger Griswold. Buchanan “has left the Government in such a state that there is scarce an opening any way for Mr Lincoln to move without appearing to be giving up some important point,” she wrote. “Whatever may occur the present administration are not to blame, had Mr Fremont been President last year, Mr Lincoln would have had a place upon which to stand while working the Lever, now there is none. The whole world seems returning to Chaos.”[6]

Captain John Griswold, age 25, died leading his company into enemy fire at Antietam in September 1862. A monument in the Griswold family’s cemetery in Old Lyme commemorates his heroism and preserves a parting message: “Tell my mother I died at the head of my company.” Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

[1] Many thanks to Patty Devoe for expert research and to Rodi York and John Noyes for special assistance. Sarah Lord Hyde to Harriet Lord Burr (February 22, 1856). Burr Papers, Box 2, folder 32, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum. Also see Philip R. Devlin, “Just How Red or Blue Has Connecticut Been in Past Presidential Elections?” The New London Day (November 8, 2012); Steve Inskeep, “It’s 1856 All Over Again,” The New York Times (January 9, 2020).

[2] The Middlesex Explorer (August 21, 1856); Katharine Ludington, Lyme and Our Family (privately published, 1928), p. 41. For a detailed discussion of Fremont’s campaign, see John Bicknell, Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856 (Chicago Review Press, 2017).

[3] Ludington, pp. 42-43. See also Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, 2019), p. 155.

[4] The Weekly Standard [Raleigh, N.C.] (November 12, 1856).

[5] Hartford Courant (November 7, 1856).

[6] Ellen Perkins Griswold to John Griswold (September 22, 1861). Griswold Papers, Old Lyme Historical Society.