About the Art

About the Painting

What do you see when you look at this painting?

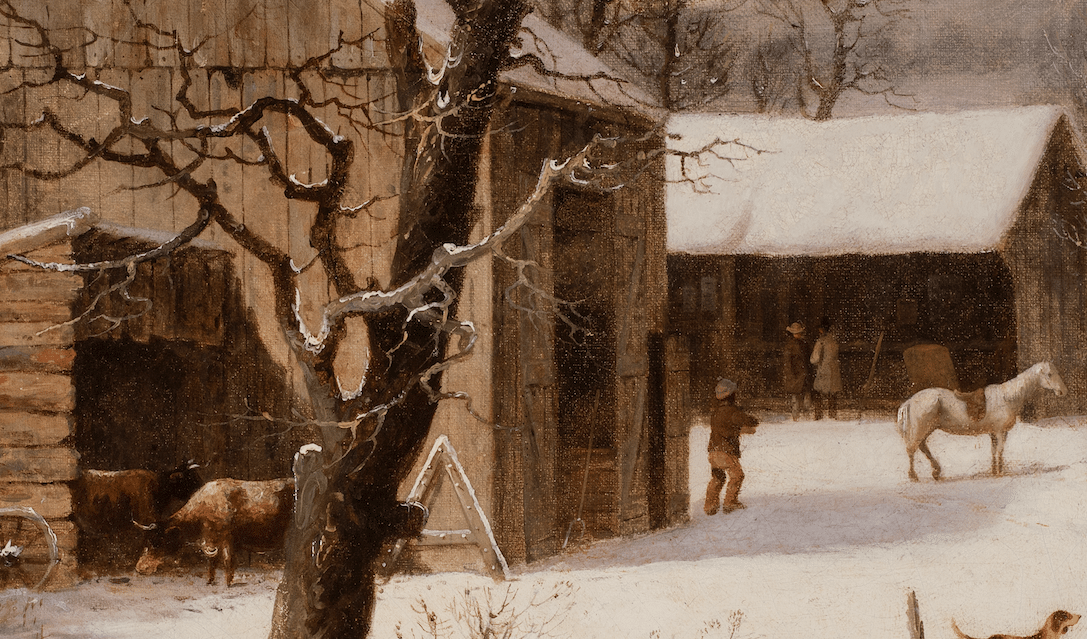

George Henry Durrie’s Seven Miles to Farmington, ca. 1853, offers viewers a glimpse into rural life in Connecticut in the mid-nineteenth century. His depiction of travelers and workers approaching a country inn on a winter day allows us to tease out information about transportation, leisure, labor, society, politics, and daily life in the 1850s—topics that are explored throughout this website. At the same time, Durrie’s idyll of Connecticut suggests the importance of an emerging sense New England regional identity.

Setting the Scene

What is the building in the center of the painting?

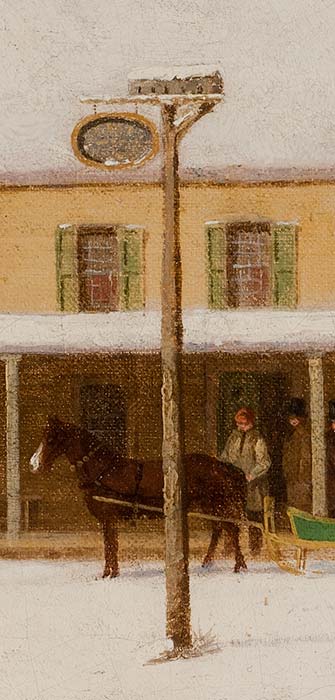

Durrie’s composition centers on an inn housed in a saltbox-style building constructed approximately a century before the moment illustrated here. Consisting of two stories, with numerous windows and a porch, the structure offered accommodation to guests both during the day for meals and rest, and, at night, for sleeping rooms, food, and even entertainment. On the right side, a party of riders in bright clothes slows their horses near the porch, where some of the occupants are helped out by staff at the inn who will welcome them indoors. Coming from the foreground, a man arrives with a different kind of sleigh, loaded down with bags that may be filled with flour from a mill. And, at the left, workers attend to customers prepared to stable their animals, or carry supplies from the cow barn toward the yellow building.

Who are the people in the painting?

On the right side, a party of riders in bright clothes slows their horses near the porch, where some of the occupants are helped out by staff at the inn who will welcome them indoors. Coming from the foreground, a man arrives with a different kind of sleigh, loaded down with bags that may be filled with flour from a mill. And, at the left, workers attend to customers prepared to stable their animals, or carry supplies from the cow barn toward the yellow building.

Composing the Picture

Why did the artist put the house in the center of the painting?

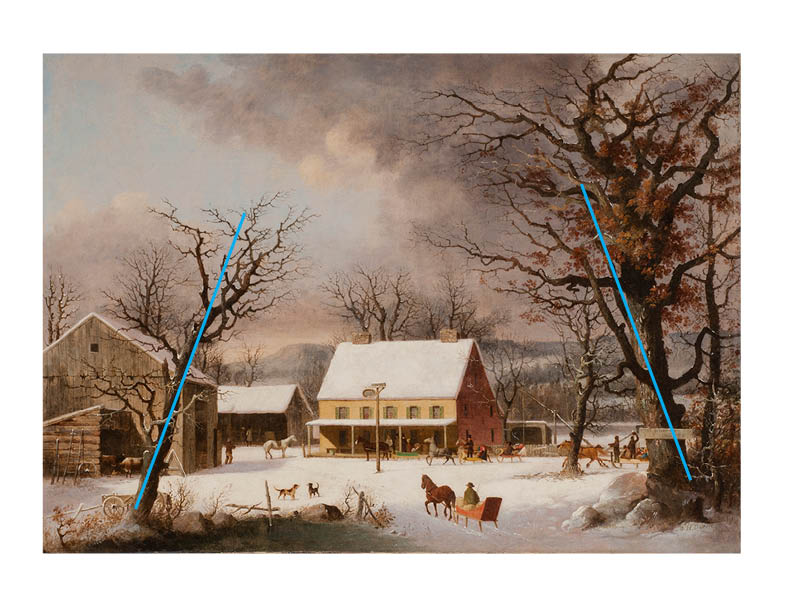

The artist arranges these and other carefully chosen details to entice viewers to look closely at the scene and to develop for themselves a story about this country inn, its patrons, and those who keep it running. Artists make choices about how to distribute the shapes on their canvases, choices that viewers can analyze to discover what the artist deemed important. Durrie’s decisions about the painting’s composition help draw our attention to the inn, which he places at the heart of the canvas. Diagonal lines from the sleigh and road in foreground lead toward the inn, as do the quickly moving lines of the sleigh party on the right. One sleighrider’s upraised arm echoes the fencepost and the well sweep, imparting a momentum that zigzags toward the inn. The vertical line of the inn’s tall sign, positioned nearly in the middle of the canvas, acts as endpoint for all these vectors, stilling the movement of our eyes and fixing them on the inn itself.

Framing the View

How does the artist create a scene that is pleasing to look at?

In addition to these directional lines, Durrie also frames the saltbox building with a large tree on the right and a smaller tree at the left, borrowing from the formula developed by the 17th-century French painter Claude Lorrain to impart a sense of balance and spatial definition to his landscapes. The trees’ tilting trunks lean toward the inn, creating a sense of enclosure. If seen from the above, the siting of the inn would amplify this sense of containment. Despite the reference to Farmington’s proximity posted on the largest tree, all roads lead to the inn, where they loop around the signpost without a clear direction onward. Further grounding us at the hostelry, a river and hills close off visual progress into the distance beyond the outbuildings and inn roof. Both spatially and compositionally, Durrie delivers us to the inn, the main character in the story he builds in Seven Miles to Farmington. He also uses color to underscore its centrality. While the surrounding landscape and farm buildings are nearly monochromatic grayish-brown surfaced with white snow, the inn glows golden yellow, its cheery hue and brilliant snow-covered roof a magnet for the brightly-accessorized sledding party at the right.

Painting as Theatre

How is the painting similar to a theatrical production on a stage?

Durrie’s decisions about composition and color “set the scene” for viewers’ focus on the inn. This theatrical allusion is no accident. Devices like the trees that bracket the composition create a sort of arch over the action, much like a proscenium that stretches over the top and down each side of a stage. In the mid-nineteenth century, practitioners of so-called “genre” painting orchestrated these views of daily life in ways that echoed the staging of plays in a theater. While genre pictures by artists such as Francis William Edmonds depict character-filled interiors where the similarity to theater is evident, outdoor genre scenes like Seven Miles to Farmington demonstrate that those framing devices could translate into landscapes as well.

What is the point of view, or vantage point, when looking at the scene?

Reinforcing the sense that we are watching a theater piece of sorts is the vantage point from which we as viewers experience this painting. Rather than contemplate this vista as we would with our feet on the ground, viewers can see the innyard from a slightly elevated perspective that allows us to look down at the action, as if from a theater seat. Largely unnoticed by the figures before us, we gaze from the darker foreground toward the action around the bright, bustling inn, ready to look and listen as the travelers, farm workers and innkeepers converge. Durrie read plays, attended theatrical performances, and painted pictures of actors in roles like Shakespeare’s Falstaff. Here, his awareness of theatrical staging may have influenced his presentation of the Connecticut countryside, and, by extension, suggests that the scene before us may combine elements of fact and fiction in a way that is in keeping with the artist’s practice of formulating his landscapes as composites of several different views.

Whose Inn?

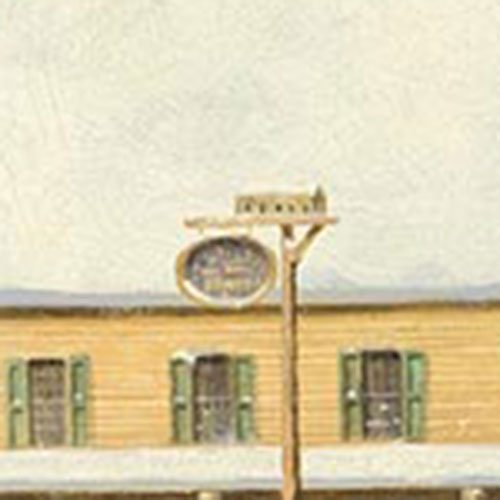

What do the signs in the painting tell us?

But for all its narrative of sleighriding and life around a country inn, Seven Miles to Farmington leaves open as many questions as it offers answers in the form of descriptive details. Key specifics are difficult to discern—for example, the inn has a sign, but we can’t decipher the name. In other versions of this 5 composition, which he repeated several times, Durrie added the word “hotel” to the sign, but left the precise name illegible. The signpost indicates we are near the town of Farmington, but not exactly where—and “seven miles to Farmington” embraces a wide circle whose diameter covers a significant area of central Connecticut. There are enough elements for us to embrace what is familiar in the scene, but at the same time, Durrie leaves telling details vague, allowing the viewer to fill them in according to their own references and memories.

What was the artist remembered for after he died?

Durrie’s obituary (1863) singled him out for this talent of infusing a painting with evocative details as prompts for reminiscence: “ We have lingered over these faithful delineations of country life greeting us from the window of our principle art emporiums on Broadway, and in our academies and galleries we were sure to find these genial and beautiful pictures from the same easel—so true to nature, and so fraught with pleasant recollections of one’s early life and bringing-up in the country.” The memorial goes on to describe how Durrie’s appreciation for detail offered a real source of pleasure for the viewer (New York Evening Post, November 11, 1863). As more people moved from country upbringings to life in urban areas, Durrie’s rural views offered opportunities for their owners to reflect on a passing way of life.

African Americans in the Painting

Why did the artist include African Americans in this painting?

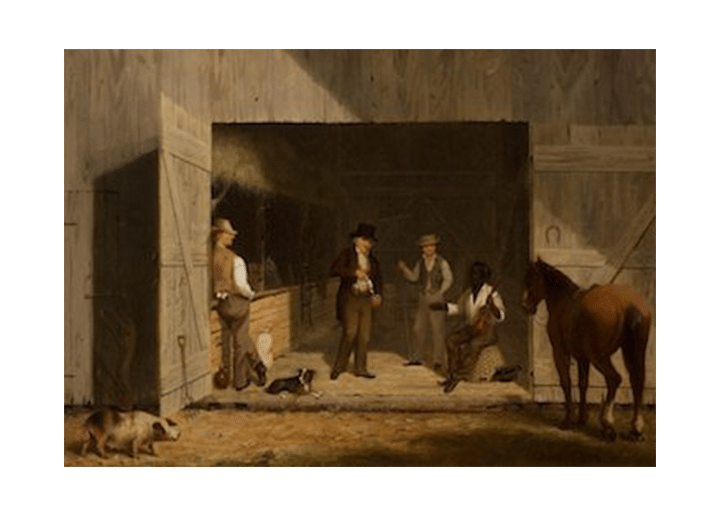

One of the most intriguingly vague details Durrie includes relates to two figures whose racial identity is uncertain. Although it is difficult to discern, the young man near the barn and a sleigh driver at the right may be painted with darker skin. The figures’ small size makes conclusions about their race challenging, but the very ambiguity corresponds to the status of African Americans in Connecticut at the time Durrie was painting. The artist did execute a couple of genre pictures with African Americans that are reminiscent of the works of the Long Island painter William Sidney Mount, which were reproduced in prints. One of these Durrie scenes, Holidays in the Country, The Cider Party (1853, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts), dates from the year of Seven Miles to Farmington and offers an overt commentary on contemporary politics and race. In it, Durrie includes both white and African American figures and inserts acronyms and symbols that imply his sympathy for the Whig party over the Democrats, which diverged in their views on the issue of slavery.

Are the African Americans in the painting slaves or free men?

Here, in a less allegorical composition, Durrie’s possible inclusion of African American figures nevertheless acknowledges their presence in Connecticut. By 1800, 83% of about 7,000 blacks in the state were free, and at the time of general emancipation in 1848 (long after other New England states), there were only six slaves left in Connecticut. Despite the elimination of slavery, free blacks were held in menial social and economic positions, and disenfranchised. During this pre-Civil War (antebellum) moment, racial tensions were high as the country struggled with the politics of slavery and its potential impact on the union. Whatever the situation in Connecticut, the majority of African Americans in the United States were slaves and had no legal rights as citizens. Durrie lived in a world of extreme racial segregation and difference, as did his audience.

What was the artist’s relationship with African Americans?

During his travels to Petersburg, Virginia, in 1845-46 in search of painting commissions, Durrie encountered larger numbers of African Americans, living there as enslaved people, and first saw the cotton fields where they toiled—both observations recorded in his diary. He noted the stir created when an orator mentioned slavery during a lecture he attended on the trip, but also employed a racial epithet in his diary to refer to the man who carried his luggage. Like Durrie, a viewer of 1853 would have very different feelings and associations for an African American figure in this painting than do contemporary audiences. Durrie’s views on the matter of race are only partially known, but his paintings existed in a world in which the issue was one of the most pressing national concerns.

What are some of the clues that there might be tension in the air?

Looking back at the painting, Durrie organizes the composition in a way that hints at underlying tensions over inclusion and exclusion. We have already observed how the viewer watches the goings on from a distance, outside the center of the action. Dogs at the left of center sniff each other in a moment of inspection that could end in a welcome or a defense of territory. Continuing this dynamic, the inn’s many windows are covered, versus the open, dark shapes of the barn and shed interiors, prompting considerations of what we can see and what we cannot, as well as who can or cannot go into the inn’s social and work spaces.

The Sleighing Party

Why are there several horse-drawn sleighs in the painting?

As described, Durrie uses composition and color to attract attention to the sleigh riders arriving at the inn. The artist’s focus in this painting on the theme of sleighing places his picture at the intersection of fashion and nostalgia. In the 1850s-60s, printing firm Currier & Ives and other contemporary publishers sold views of couples sleighriding in urban settings, including parks, but the “sleigh party” of the sort seen in Seven Miles to Farmington was very much identified with rural life of a passing age. These multi-generational affairs were a core element of country life that allowed for courtship as well as social interaction in the winter months. Durrie himself noted with frequency in his diary time spent sleighing, purely for amusement.

How did people riding in sleighs keep themselves from freezing?

In 1878, Hartford novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about a sleighing party at an inn in Poganuc People, a tale based on her youth in Litchfield, Connecticut. The details she includes in her text could describe Durrie’s canvas. In her account, couples tucked in “under a profusion of buffalo robes” “went jingling away” behind prancing horses. According to Stowe, “A supper and a dance awaited them at a village tavern ten miles off, and other sleighs and other swains with their ladies were on the same way….” Stowe mentions the sleigh riders receiving hot bricks under the robes to keep them warm as they collect members of the party around town. Festive company was one appeal of sleighing, but so was the weather, “The keen clear air was full of stimulus and vigor,” Stowe writes, enticing the riders to go the long way to the inn to better enjoy the sensation of flying over the snow like birds. After “eight miles,” a number close to the seven miles referred to on Durrie’s sign, “the party drove up to the great red farm-house, whose lighted windows sent streams of radiant welcome far out into the night.”

What was it like inside an inn like the one in the painting?

Stowe’s Poganuc People also lets us see inside an inn like Durrie’s. When the sleighing party arrives, she writes “The fire that illuminated the great kitchen of the farm-house was a splendid sight to behold,” fed by logs that were once “giants of the forest.” By the 1870s, when Stowe was writing, this sort of timber was a “memory of the past,” due to deforestation in New England, but what she called the “hearty, bright, warm hearth” was recalled as the essence of “country and home.” Durrie’s Seven Miles to Farmington and other rural snow scenes by the artist tapped into this vein of nostalgia with their references to a lost era of natural bounty and wholesome, sociable country life. The power of Durrie’s vision contributed to the popularity of his paintings at the time, and they came to represent New England as a region.

Why are the people not arriving by car?

Riding by sleigh to an inn in the country offered opportunities to enjoy a traditional pleasure of New England life, but of course horse-drawn vehicles were no longer the only way to travel between towns or across the countryside by the 1850s. In the absence of a national system, Connecticut (like other states) relied on publicly chartered but privately owned turnpike corporations to construct roads and other means of transportation. There were 120 turnpike corporations chartered in Connecticut, and during their existence they built 1,600 miles of dirt turnpike roads. Two of these seem to converge at Durrie’s inn, past the sign alerting travelers how far away the next town is (inns were spaced typically every 12-18 miles). These turnpikes spawned a large carriage industry in the state as well as a stagecoach network.

How did people in the 1850s travel other than by horse-drawn sleighs?

At the same time, these roads allowed communication, mobility, and trade. To supplement turnpikes, canals were built as another means of transportation for goods and people, albeit one whose heyday in Connecticut was short. The reference to Farmington in the title of Durrie’s painting raises the question of whether the water running behind the hotel could be the Farmington Canal. These manmade waterways were soon displaced by the railroads, which were built in Connecticut between 1830 and 1870, and ultimately consisted of over 1,000 miles of track covering all parts of the state. Railroads also offered up the opportunity for more extensive travel, especially to the West, and created a conduit for resources to travel back east. One example of these goods moving cross country is buffalo robes. Harriet Beecher Stowe refers in Poganuc People to her sleighriders’ buffalo robes, which are also present over the sleighriders in Durrie’s painting—a little bit of the Great Plains brought to Connecticut. While Durrie composes a scene with few visual outlets, the world he depicts is implicitly linked to the rest of the country via expanding transportation networks.

What else can we learn from this painting?

These observations about Durries’ Seven Miles to Farmington provide only an introduction to the rich content teachers can draw upon with their students. As objects created in the past, but that survive today, paintings are key documents of the world in which they were made, and a resource for students of history and social studies.

Have a question or comment regarding SEE/change? Enter your email and comment here.

"*" indicates required fields