About the Artist

Where did the artist live?

George Henry Durrie was born in Hartford, CT in 1820. He lived all of his life in New Haven and died there at the age of 43. While Durrie never achieved the fame of the most renowned nineteenth century American landscape painters, he appears to have had a fulfilling, productive career. His letters show that he never felt the need to move beyond his community, although he once briefly took a studio in New York, and exhibited there regularly at the National Academy of Design.

George H Durrie (1820-1863) Self Portrait, 1843. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

What did the Durrie family do in New Haven?

Durrie’s ancestors came from England to settle in Hartford. At some point the family moved to New Haven, and it was there that Durrie’s father established the company Durrie & Peck, which served the public as publishers, booksellers, and stationers.

Early Art Career

How did the artist become an artist?

George Durrie was part of a large family, as one of six children. Both he and his brother John studied to be artists with the leading local portraitist Nathaniel Jocelyn in New Haven. After completing his lessons, Durrie worked on bank note engraving, and painting portraits and miniatures. The artist came from a religious family and was deeply religious himself, attending church each week; he sang in the church choir, and played musical instruments.

George H Durrie (1820-1863) Mrs. John Forman, 1841. Oil on canvas. Private Collection

What kinds of paintings did the artist make?

He spent the first half of his life as a portrait painter, creating portraits like this one. Working as a portraitist required the artist to frequently travel away from home to complete portrait commissions, and on these journeys he took pleasure in visiting many churches, lodges, and attended local musicals. During this time of excessive travel you can imagine that he may have also stayed at local inns. However, Durrie hated being away from his family. He had married in 1841, and with his wife Sarah had three children. Up until this time he painted portraits and also still lifes, fireboards, and decorative window shades. However in 1845 he shifted his focus from these works to landscape.

The Snow Pictures

When did the artist start painting landscapes?

By 1845, local newspapers carried advertisements for Durrie’s ‘snow pictures’ and his Sleighing Party was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in that year. Landscapes, which had first appeared as backgrounds in his portraits, became his primary focus. He painted local landmarks such as East Rock and West Rock (East Rock, New Haven, 1862), as well as composite scenes of rural life. Country inns and barnyards, scenes of human activity, became his most oft-used subjects. While he painted these in all seasons, his depictions of winter were most numerous, growing in frequency between 1854 and 1863.

George H Durrie (1820-1863) East Rock, New Haven, 1862. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Insurance and Inspection Company

Landscape or Genre Scene?

What’s the difference between a landscape and a genre scene?

One may approach Durrie’s landscapes from a portraitist’s point of view, since the artist seems more interested in the character of a place and its people rather than delineating specific aspects of the land. Works like this one, Seven Miles to Farmington, is not actually a pure landscape, but rather a blend of a landscape and what art historians call a genre scene—or a scene of everyday life.

What are the five genres of painting?

Within the history of art there is also a hierarchy of genres, or an organization of types of art work which were most esteemed by the Academy des Beaux Arts in France. This organization began with history painting (historic events or scenes from the Bible) at the top, then portraits, then genre painting, landscape, and still life. When Durrie changed his primary occupation from portrait painter to genre painter, he took a step down in a way, but he had good reasons for doing this. Firstly, he wanted to stay close to home in New Haven with his family. And second, he was likely very knowledgeable about the market for genre scenes, which were popular and could be sold to a wider audience, and as we will see, were also mass-produced to reach an even larger audience.

How did the Industrial Revolution impact the art world?

Today, Durrie is known almost exclusively for his landscape/genre scenes. Genre scenes are often domestic scenes or scenes of rural life (such as Seven Miles to Farmington) which were very appealing to Americans during the time of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution spanned 1820-1870, corresponding exactly with Durrie’s lifetime. During this period, modern industry provoked a lot of anxiety within the American psyche and many yearned for nostalgic images as souvenirs for a simpler time—Seven Miles to Farmington certainly qualifies here and fills that need.

Durrie and American Art

Who were the other painters working at the same time as artist?

So where does Durrie fit within the canon of American art? Durrie was a contemporary of the Hudson River School of American landscape painters. The Hudson River School was a New York-based group and America’s first true artistic group or fraternity. They were led by Thomas Cole, who made this work Study for A Wild Scene (1851). Other artists in the group included Cole’s student Frederic Church, as well as John Kensett and Asher B. Durand. Frederic Church was the most famous artist in Durrie’s day—this is an example of his work in the Museum’s Collection Hudson River School landscapes can be characterized by their realistic portrayals of nature, sometimes in exacting detail, but often also idealized. These artists generally associated nature with the manifestation of God; they appreciated the rugged and sublime qualities of nature. Durrie was able to see work by these artists thanks to accessibility of the railroads. The railroad linked New Haven to Hartford and New York City. We know that Durrie went to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford to see examples by Cole and others.

What did the artist learn from other painters?

In some respects, Durrie’s work shows an indebtedness to Cole and other Hudson River School painters, especially in the backgrounds, which show an attention to atmospheric effects. Still, it’s clear just by these brief comparisons that Durrie was interested in something very different—much more in the details which contributed to a narrative of everyday life, rather than these sublime scenes with religious and moral connotations.

The "Snow Man"

Why are snowy landscapes less common?

Seven Miles to Farmington is a New England winter scene, which became Durrie’s specialty. Winter scenes were not as common as scenes painted in other seasons for the practical difficulty of working outdoors in the cold. (The Hudson River School did not typically make winter scenes, as its members ventured into the countryside in the summer and worked in city studios in the winter.) But Durrie excelled in winter scenes, and made many pictures of sleighing, cider making, getting ice, and other aspects of farm life.

Diary Entries and Sketchbooks

What kinds of records did the artist leave behind?

What we know about Durrie—which is not very much compared to other artists of his day (like the Hudson River School)—can be gleaned from his account books (1839-1852) and a diary he kept between 1845 and 1846. The account books document the artist’s commissions, sales, and exhibitions, while his diary offers insights into his personal affairs and interests. One of his daughters also kept a diary and it is from her that we know a little about Durrie’s process.

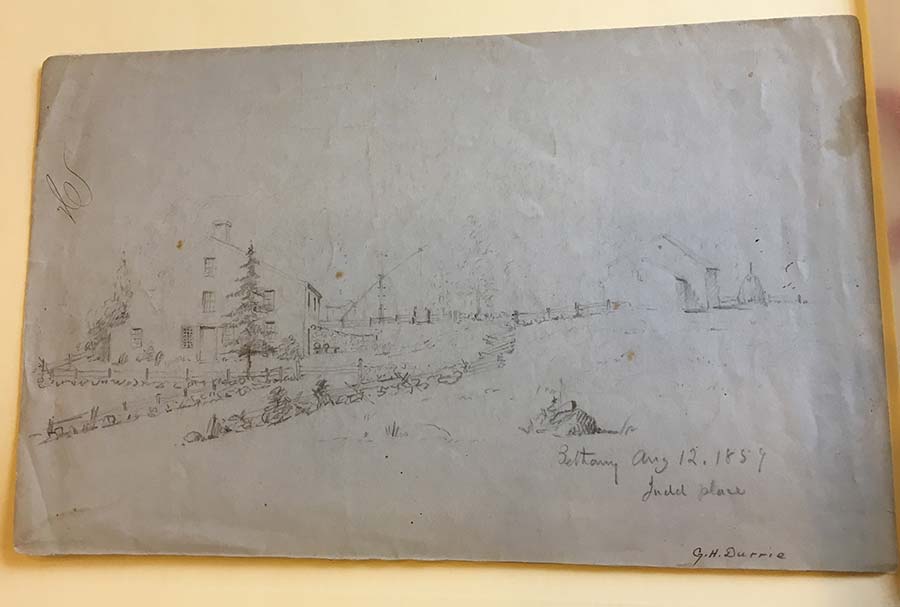

Image from Sketchbook. New Haven Museum.

How did the artist use his sketchbook and photographs in his art?

We know that the artist took walks with his daughter and stopped often to study the trees, admire a farmyard, or examine a stone wall. His daughter recounted that upon returning home Durrie would disappear into his study to make sketches of what he had seen. His sketchbooks are filled with drawings of trees and landscape arrangements. He would use these studies when creating his larger oil works in the studio—like Seven Miles to Farmington. Durrie repeated in numerous paintings elements like the trees or the buildings you see in this painting, and must have drawn upon his sketchbook for the source material. At the same time, Durrie and his brother experimented with photography after its introduction in the late 1830s. The artist used photographs as memory aids and had his works photographed, which could explain the ease with which he repeats elements across different compositions.

Prints of Durrie's Paintings

How did the artist’s work become so famous?

The printmaking firm Currier & Ives were famous for reproducing prints by fine artists in black and white that were then hand-colored. They were based in New York from 1834 to 1907. In 1861 Currier & Ives helped to popularize Durrie’s work by publishing two lithographs of his winter landscapes, New England Winter Scene (1858) and the Farmyard in Winter (untraced). Two more of Durrie’s works were published in 1863 and a further six after his death (total of 10). The last print to be published was Home to Thanksgiving (unknown) in 1867. It depicts a young man, having returned home by sled, being greeted by his family on the front porch of their home. It has become one of the most Durrie’s most iconic images.

New England Winter Scene, 1858. Lithograph. Published by Currier & Ives, 1861, after a Durrie painting, 1858, with the same title.

How are paintings and lithographs different?

As the son of a book printer and seller, Durrie must have recognized the power of print, and how reproductions could put his works into the hands of more people. He also worked with another print firm to reproduce two of his paintings of New Haven.

Because Durrie’s works were reproduced by Currier & Ives, they attained widespread popularity, not typical for many other 19th-century landscape paintings. Durrie’s name wasn’t as widely known, but images by him that were reproduced by Currier & Ives came to stand for our image of the New England countryside.

Why are Currier & Ives images so recognizable?

The prints were purchased in the 19th century, and rediscovered by antique collectors in the 1920s. Starting in 1936, an employee of Travelers Insurance began to put Currier & Ives prints in the company’s annual calendar, given out to policy owners and as an advertisement. Durrie’s work appeared as the January page for decades, from the 1940s to the 1970s. Currier & Ives prints of Durrie images were also reproduced on Christmas cards and collectibles.

A Short Life Ends

When did the artist die?

Durrie’s life and artistic career was as quiet and tranquil as his winter paintings. He died in 1863 of unknown causes at home.

His obituary in the Columbian Register of New Haven, CT on October 24, 1863 reads in full:

The death of Mr. George H. Durrie, in the prime of life, and in the midst of his usefulness, has cast a shade of gloom over our city. Mr. D. was a useful and a good man; and in the famiy, the neighborhood, or the church, was always the same active, cheerful and kind-hearted man. Mr. D. had risen to the front rank as a landscape painter, and acquired a national reputation—and his last piece, entitled “Autumn,” is considered his crowning composition. He was unobstrusive in his life, and probably shared to as great an extent as any one the respect of the community.

How was the artist remembered?

His obituary in the New Haven Daily Palladium, CT on October 16, 1963 reads in full:

The Death of George H. Durrie. The numerous and ardent friendships existing between this gentleman and our citizens have been severed by the hand of death. After a somewhat protracted illness he passed away on Thursday morning. But in addition to the pleasant memories of his personal characteristics he has left behind many memorials of his genius, which are scattered abroad—productions of a pencil that are admired by the lovers of nature faithfully transcribed by art. His accomplishments as a musician, too, were of a high order, and he has been associated with the best choirs in the Episcopal service of the city for several years past. His funeral will be attended by the book-publishers, musicians and artists of New Haven, who desire thus publicly to testify their affection and respect for his memory.

Have a question or comment regarding SEE/change? Enter your email and comment here.