About the Location

About the Landscape | What time of year is it? | What time of day is it? | When did it last snow? | Thinking more about the snow… | Why are there leaves still on the tree in winter? | What did 1850s Connecticut look like? | What about the rocks in the painting? | What about the snow and ice? | It was colder back then… | One Theory on the Location of the Scene

About the Landscape

How much of the painting is about nature?

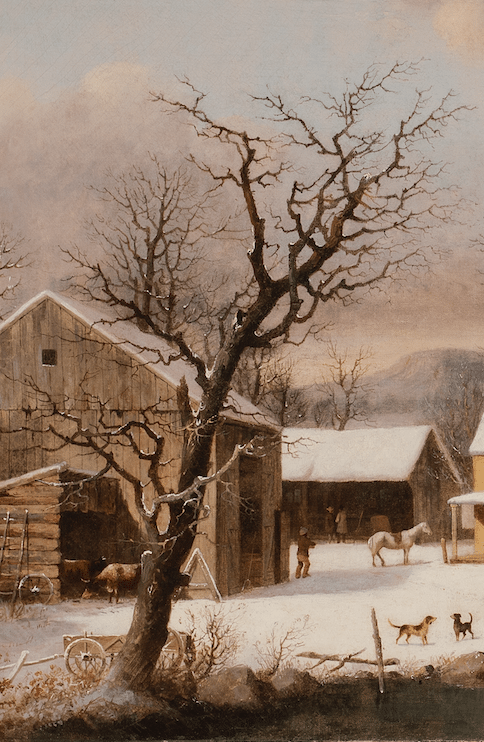

Measured by canvas area, the most important component of the painting appears to be raw nature. The top 70% of the canvas (estimated) contains nothing but land, sky, clouds, trees, and land. All of the people are painted in the lower 25% of the canvas.

What gives Connecticut its distinctive geography?

The Connecticut landscape in Durrie’s painting is one that took over 200 million years to develop. Present-day Connecticut was part of a large land mass called Pangea (meaning “all one earth”), a supercontinent into which all of the earth’s continents were connected by tectonic forces. At this time, Connecticut’s terrain was a series of accordion folds that run north and south due to the state being compressed within this larger landmass. Slowly, over the course of millennia, the land was ripped apart, the continents heading in opposite directions, and drifting over the surface of the earth. The ocean water filled in between the now separated landmasses. Parts of Connecticut were actually once connected to parts of present-day Africa.

How was Connecticut impacted by the Ice Age?

Then came the most recent ice age, when Connecticut was covered by an ice sheet thousands of feet thick. The ice was instrumental in defining the terrain of the state, both while forming and again while melting. Glaciers pick up rocks and other material while forming, then distribute them in new places while melting. When this ice melted, the water filled present-day Long Island Sound. The boulders, rocks, and soil left behind created the landscape that is recorded in Durrie’s painting.

Are there other paintings similar to this one with same landscape?

The painting’s title, Seven Miles to Farmington, comes from the road sign nailed to the tree on the far right. The sign is telling the viewer that this country inn is seven miles away from Farmington, a town near the center of the Connecticut, west of Hartford. However, the artist painted this distinctive yellow saltbox building as well as the rustic barn and other outbuildings in a number of his paintings. These other paintings have different towns and various mileage numbers in their titles such as The Old Inn—Ten Miles to Salem and Winter at Jones Inn—Nine Miles To Hartford. There’s even another with the title Inn Scene Near New Haven (this one will be of interest as we look closer at the distinctive landscape elements in the painting later).

Is this a painting of a real place?

It appears that Durrie is not actually painting a particular house in its original location, but rather using a repertoire of favorite images to create an imaginary, albeit convincing scene. As a creative painter, he can move the house, barns, and sleighs about at will, and place them in a setting of his choice. Nevertheless, his choices are based on things observed in the world around him, and we can investigate these decisions through the lens of a geologist with keen observations on the landscape, the quality of natural light, boulders, trees, and the weather.

What time of year is it?

How can you tell the season is winter?

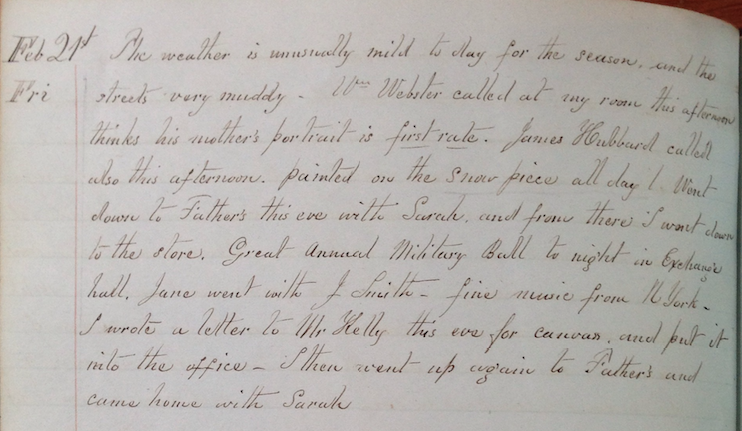

Durrie himself identified winter images such as Seven Miles to Farmington as his “snow” pieces. On Friday, February 21, 1845 he writes in his diary, “Painted on the snow piece all day.” Indeed his diary of 1845-1846 is filled with daily accounts of the weather as well as the sleighing conditions. This painting is a great example of his “snow” pieces. The roofs of the house, barns, and shed are layered with inches of snow. The snow covering the inn yard is less deep, most likely due to heavy sleigh and foot traffic, but no bare earth is visible.

What time of day is it?

Can you guess the time of day based on clues in the painting?

It is interesting to use an understanding of sunlight and shadows to determine the time of day depicted in the painting. The front of the inn most likely faces toward the south, taking advantage of the maximum sunshine year-round. If that is true, the time depicted is most likely late afternoon, with the sun setting in the west (the left side of the painting). Because the winter sun hangs low in the sky, its harsh white light pours into the inn yard at a sharp angle, illuminating the front of the yellow house while plunging the east-facing façade into shadow. The shadows cast by the barn, the sign pole, and the roof of the porch suggest that the sun is still quite high in the sky. The shadows would all be longer if it were later in the day, when the sun is nearer the horizon. However, not all of the light clues in this painting need to be consistent with light’s performance in nature. As an artist, Durrie is more concerned with composing an image that is pleasing to the eye, rather than slavishly documenting the precise light at a distinct moment in time.

When did it last snow?

What do the tracks in the snow tell us about the painting?

The red sleigh entering the inn yard is making seemingly fresh tracks in the snow that appears only an inch or two deep, consistent with the depth of the dog footprints. The new-fallen snow is fluffy and fell down vertically under dry windless conditions like those associated with very cold weather. A wetter snow, or one from a windstorm, would have stuck on the sides of the trees or barn. The frozen pond behind the house appears free of snow. It’s not likely that the pond could have recently been blown clear, because such a wind would have also removed the delicate snow accumulations on exposed horizontal surfaces like fence rails and tree crotches. This means the artist is assembling different images into a created scene.

Thinking more about the snow...

What does the height of the snow in various parts of the painting tell us?

The roofs of the buildings consistently show snow accumulations of four to eight inches. Because snow would typically melt slightly on a roof in the sunlight, the amount we still see would have been deposited in one or more earlier snowfalls. The fact that the dogs and horses are moving through much thinner snow suggests that either the former snow melted off near the ground or became hard-packed or frozen due to the heavy use of the inn yard.

Why are there no icicles on the buildings?

If it’s early in the season, the snow falling on the ground would melt because of the heat of the ground still warm from autumn. The lack of heat in the barns and upper floors of the house would allow the snow to stay frozen. However, the empty woodshed might suggest that it’s late in the season and much of the heating fuel has been used up. Either way, the lack of icicles along the rooflines suggest that the weather has not been warm enough to melt the snow off the roof.

Why are there leaves still on the tree in winter?

What kinds of trees retain their leaves into winter?

The leaves that remain on the tree to the right could suggest an early snow, closer to fall. However, there are certain trees that retain their leaves through the winter such as oak and beech. Although the tree is somewhat stylized by the artist, the size and shape could be an oak, a species cherished in Connecticut because of the famed Charter Oak of Hartford. It’s important to note the lack of conifers (evergreens) in the painting, most likely because pines were harvested for timber and cordwood. The single tree behind the house on the right (north) has a regular, Y-shaped branching pattern typical of a planted elm. Durrie’s sketchbooks contain drawings of trees that intrigued him, and he especially gravitated toward trees with gnarled, twisting branches.

What did 1850s Connecticut look like?

Why is the farm so isolated?

In the background of the painting it appears that agricultural fields are still being cleared of trees. This farmhouse is the only building visible for miles. The lack of urbanization is consistent with the date of the painting (ca. 1853), and of Durrie’s lifespan (1820-1863). Both are close to the historic tipping point of 1859 when industrial output for the United States first exceeded its agricultural output.

Why are there so few trees in the painting?

The creation of this painting coincides almost exactly with the beginning of the return of forest to the Connecticut landscape. At one point in time, Connecticut was 72 percent de-forested following centuries of European colonists harvesting timber. By the 1850s, trees had become more scarce and thus more highly valued, which may explain why the oak is the largest single thing in the painting.

How does the painting show nature being tamed by man?

Durrie’s painting also shows that trees are being retained along property lines to mark these boundaries. Boulders are being scuttled aside. Streams are being dammed for ponds. Wellsweeps rather than pumps are being used to bring fresh water to the surface for drinking and cooking. All of this is consistent with the mid-19th century.

What about the rocks in the painting?

Why did the artist include rocks and boulders in the painting?

Because of glacier activity after the last ice age, Connecticut is a land riddled with rocky outcroppings and a very stony soil. Farmers created long stonewalls outlining their fields with the stones harvested from the ground. Though stone is featured in this painting through a few boulders to either side of the road into the farm, there are no stonewalls.

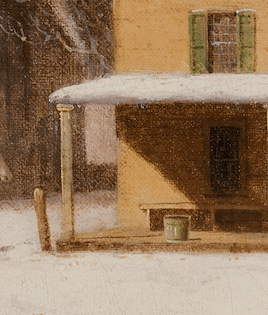

What is the difference between the cobblestone chimney and the granite post in the foreground?

The inn’s chimneys are composed of cobblestone (or small rounded boulders), which is consistent with the setting on a glacial meltwater terrace. One rather odd element is the single granite post to the left of the entrance. This post is made from quarried stone that was shaped by a mason using a great deal of labor. Such a grand post doesn’t make sense on such a humble farm, but Durrie does include such posts in other paintings as well. Perhaps the post was just one of his favorite shapes to paint, or was a detail he observed in a different context and repeated elsewhere, regardless of logic.

What about the snow and ice?

Where and how is water represented in the painting?

All of the water in the painting is presented in its solid phase, as either snow or ice. Other Durrie paintings with similar compositions show that the dark area in the foreground is also a small area of frozen water. There is what appears to be a frozen body of water behind the house as well. The surface of the ice on the pond is reflective, indicating that it is not snow-covered. A farmhouse such as this would get all the water for cooking and cleaning from a dug well. Although the actual well is not visible in this painting, the wellsweep (the long pole with rope attached used to lift heavy buckets of water out of the well with ease) is to the right of the house behind the fence. The length of the rope suggests the depth of the well and a water table of approximately 20 feet. This observation is consistent with the level of the frozen water just slightly down the slope from the house.

It was colder back then...

What is the temperature of the scene in this painting?

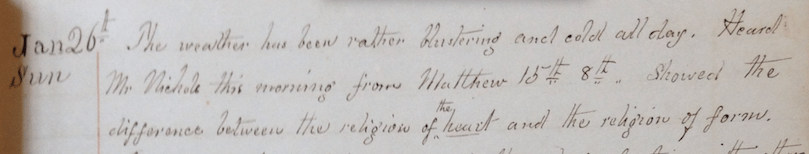

There are two dates relevant to this painting. The interval between 1850-1880 marks the end of the so-called “Little Ice Age” and the beginning a natural warming of the planet. This climate change coincides with the years during which Durrie executed all of his winter paintings. Indeed, while Durrie was painting these scenes, his winters were colder and longer than those experienced today. In fact, Durrie’s diary of 1845-46 is filled with observations about the weather. On January 26 of 1845, Durrie’s entry includes “The weather has been rather cold and blustering all day.”

Why are the winters less cold these days?

There has been dramatic warming since the 1980s due largely to anthropogenic warming, or global warming caused by human activity. Present day winters, especially in New Haven, are notably warmer than in 1853.

One Theory on the Location of the Scene

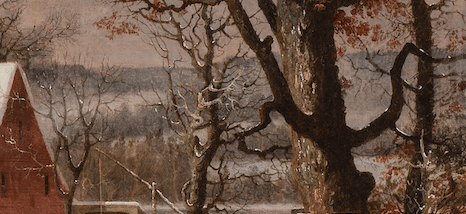

Can the mountains in the background of the painting be identified?

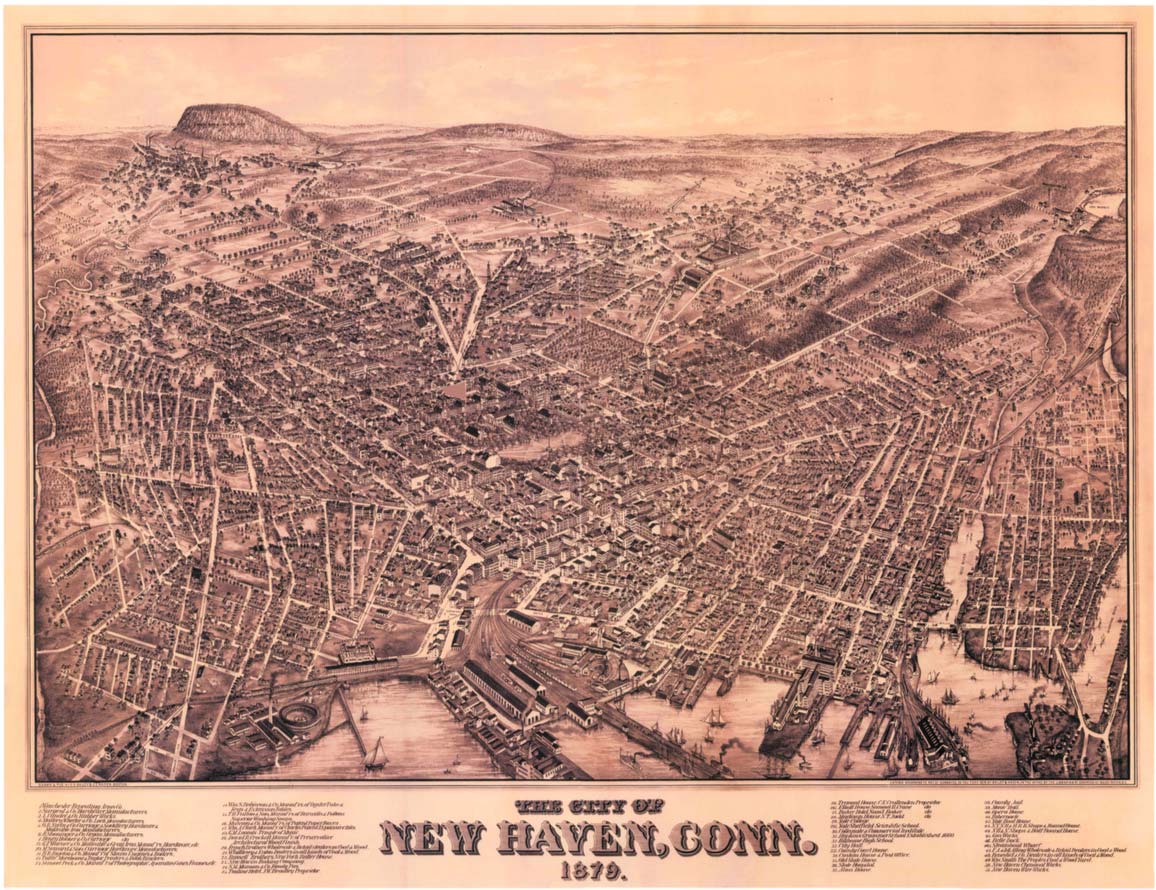

Despite the different titles of similar Durrie paintings naming various towns, the mountain bluff that is visible to the left side of the saltbox closely resembles West Rock, a recognizable landmass that is just north of New Haven harbor, in southern Connecticut. The painted version features the height, shape, tell-tale palisaded cliff, and accumulation of broken rock, or talus, of the landmark.

Can the point of view of the painting be determined by the shape of the mountains in the background?

Comparing the view in the painting with the real world, it’s possible to consider where the scene might actually be. Because the south face of West Rock is shown obliquely, the scene must originate from considerable distance to the east, but not so far north as to lose a view of the cliff face. Also, the point of view in the painting is from a flat, well-drained surface or terrace, which appears to be about 10 to 30 feet above the elevation of the surface of the narrow millpond behind the house. On the other side of the millpond is another terrace of comparable elevation, above which rise a series of irregular hills and ridges. This elevated, more irregular topography rises to a much bolder, continuous ridge that defines the horizon. It is this ridge that terminates to the left at West Rock.

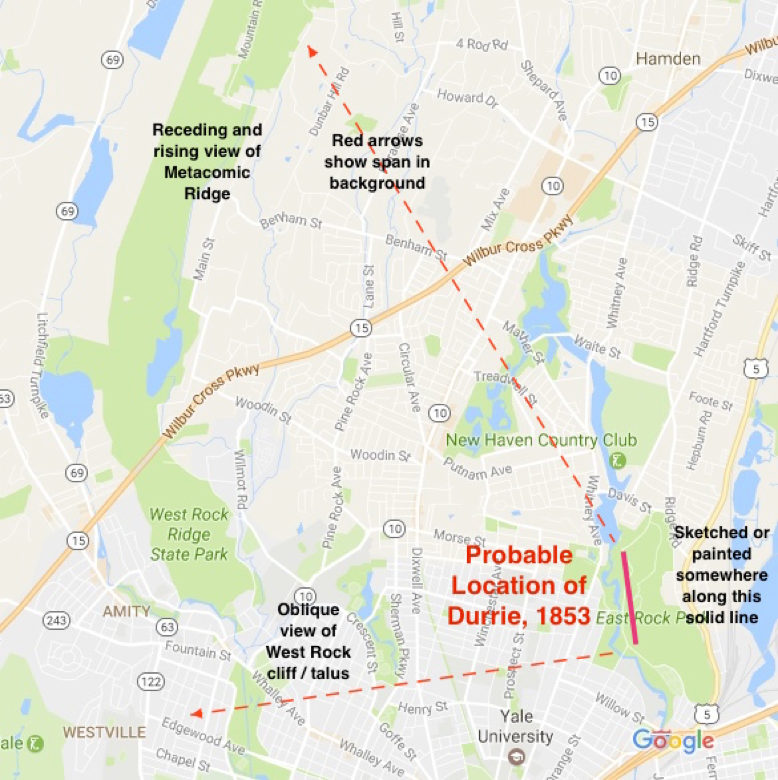

Taking the angle of view of West Rock and comparing a map of New Haven to find appropriate waterways, Geologist Thorson proposes the possible site where a similar landscape view is possible.

What other clues in the painting help tie it to the specific locale near New Haven?

Putting all these elements together indicates with a fair degree of certainty that the viewpoint for the painting (not necessarily the location of the saltbox) is somewhere in or near the present-day East Rock Park. From that point, the view is west out over the terraces of the lower Mill River to rising hills that are sharply backed up by the ridge rising north of West Rock. The map shows the viewpoint located somewhere along the solid red line shown on the diagram, and the cone of vision indicated by the dotted red lines.

Was this location convenient for the artist to sketch?

This location is not far from where Durrie lived in New Haven and it was common for the artist to wander near to home observing nature and capturing small details in his sketchbook.

What proof is there that the artist appreciated the mountains near New Haven?

The collection of paintings Durrie completed of both East and West Rock offer further evidence that this local landmark was a favored by the artist. His affection for the colossal rock formations and motivation for including them in his paintings in clear in Durrie’s remarks of 1854, the year after Seven Miles to Farmington was completed.

Every admirer of New Haven scenery is particularly struck with the boldness and beauty of the two mountain bluffs, “East and West Rock,” which stand like sentinels on either side of this highly favored city. They are the first objects of interest that strike the eye on approaching the city, and are looked upon by every New Havener with feelings of pride and satisfaction. What pleasure, then, would it not afford every citizen of New Haven, whether at home or abroad, to possess beautiful and perfect facsimilies of those charming spots.

Have a question or comment regarding SEE/change? Enter your email and comment here.

"*" indicates required fields