Fox Chase

American Impressionism

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

When Childe Hassam arrived in Old Lyme in 1903, he provided a change in leadership and artistic direction for the painters.

He introduced an Impressionist style, derived originally from French Impressionism but adapted to the New England setting that quickly became the colony’s signature style. American Impressionism, like its European inspiration, featured bright colors and painterly, broken brushstrokes that sought to capture the fleeting emotion, or “impression” of a scene.

Unlike their French paintings, however, the subjects did not derive from the modernity of urban Paris, but rather presented a fresh look at rural New England. Theirs was an American art, inspired by the Nation’s New England roots.

The Impressionists, both in France and America, sought freshness and immediacy. Using newly available collapsible and portable paint tubes, they often layered thick brushstrokes of paint upon the canvas to suggest the light hitting their subject, enhancing the color and form. Inspired by Japanese prints and black and white photography, their compositions incorporated areas of flat color and pattern with abrupt cropping, slight blurring of edges, and intriguing juxtapositions.

Unlike the French prototype that depicted scenes of modern life, the American Impressionists painted a more selective view of America. Their paintings emphasized the pleasantries of small town life and generally omitted blatant evidence of modernity including automobiles and telephone poles. In Connecticut, the rural and picturesque landscape was paramount to the Impressionist artists, not only in Old Lyme, but also in Cos Cob, Noank, and Mystic.

Although the Tonalist and the Impressionists artists were painting the same types of subject matter, for instance the rural landscape around Old Lyme as well as the old New England homes, churches, and gardens, their approach was quite different. The specific characteristics found in many works of American Impressionism are outlined below.

Wilson Henry Irvine (1869-1936)

Monhegan Bay, Maine, c. 1914

Oil on panel

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George M. Yeager in Honor of the Centennial

Characteristics of American Impressionism

Asymmetrical Balance

Impressionist painters both in France and America were interested in capturing a sense of immediacy.

They emphasized new compositional devices such as plunging perspective, cropped forms, and compositions balanced asymmetrically. Earlier painters going back to the Renaissance favored more closed and clearly balanced compositions. Often pyramidal in form, the central image was flanked on either side with similarly weighted forms.

These artists tended to create landscapes that were framed on each side by trees or other structures, and where recession into space was created by carefully measured intervals. Impressionist painters favored asymmetrical compositions such as that employed in this work by Edward Rook where the bushy laurel below is visually balanced by the tree above.

Edward Rook (1870-1960)

Laurel, c. 1905-10

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

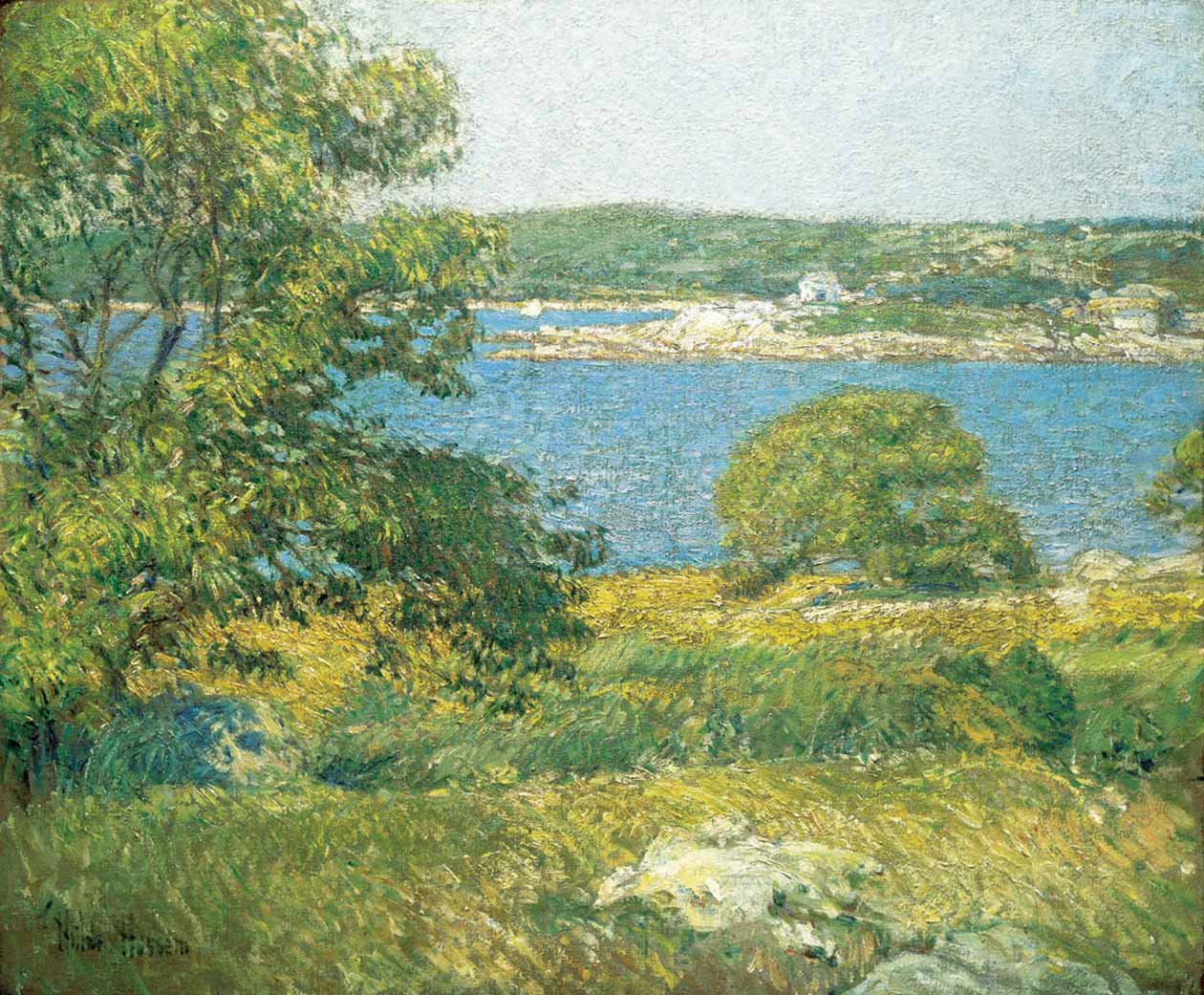

Use of Colored Shadows

Depicting light and the play of shadow has long been a concern for painters. Generations of painters before the Impressionists used neutral tones and black and grays for shadows. The Impressionists abolished this way of creating shadow by using color instead. Many artists employed purples, yellows, and other colors to suggest colored shadows and reflected light. In so doing, they heightened the coloristic effects that captured their attention when painting in the open air. Hassam uses a range of dark greens and even blues to suggest shadows beneath the tree or at the edges of boulders.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935)

Ten Pound Island, c. 1896

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Use of Pure Color

Artists traditionally mixed paints on their palette to achieve a certain hue or color before applying it to the canvas. Some American Impressionists, like their French counterparts, broke with this formula by employing pure, prismatic colors fresh from the new tin tubes unmixed on the palette and laid directly on the canvas. Upon close inspection each hue is applied separately but would be visually fused together by the human eye giving the sensation of flickering light and vibrating atmosphere.

In this painting, Foote does not mix his paint on the palette but rather appears to have applied it directly from the tube onto the canvas. He intensifies his palette and uses bright purples, greens, and yellows to convey the intense light and color and heat of a summer afternoon in the garden. These qualities are enhanced when one realizes that Foote rejected the use of firm outlines and smooth surfaces for a loose handling of pigment and thick impasto.

Will Howe Foote (1874-1965)

Summer, c. 1913

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert H. Krieble

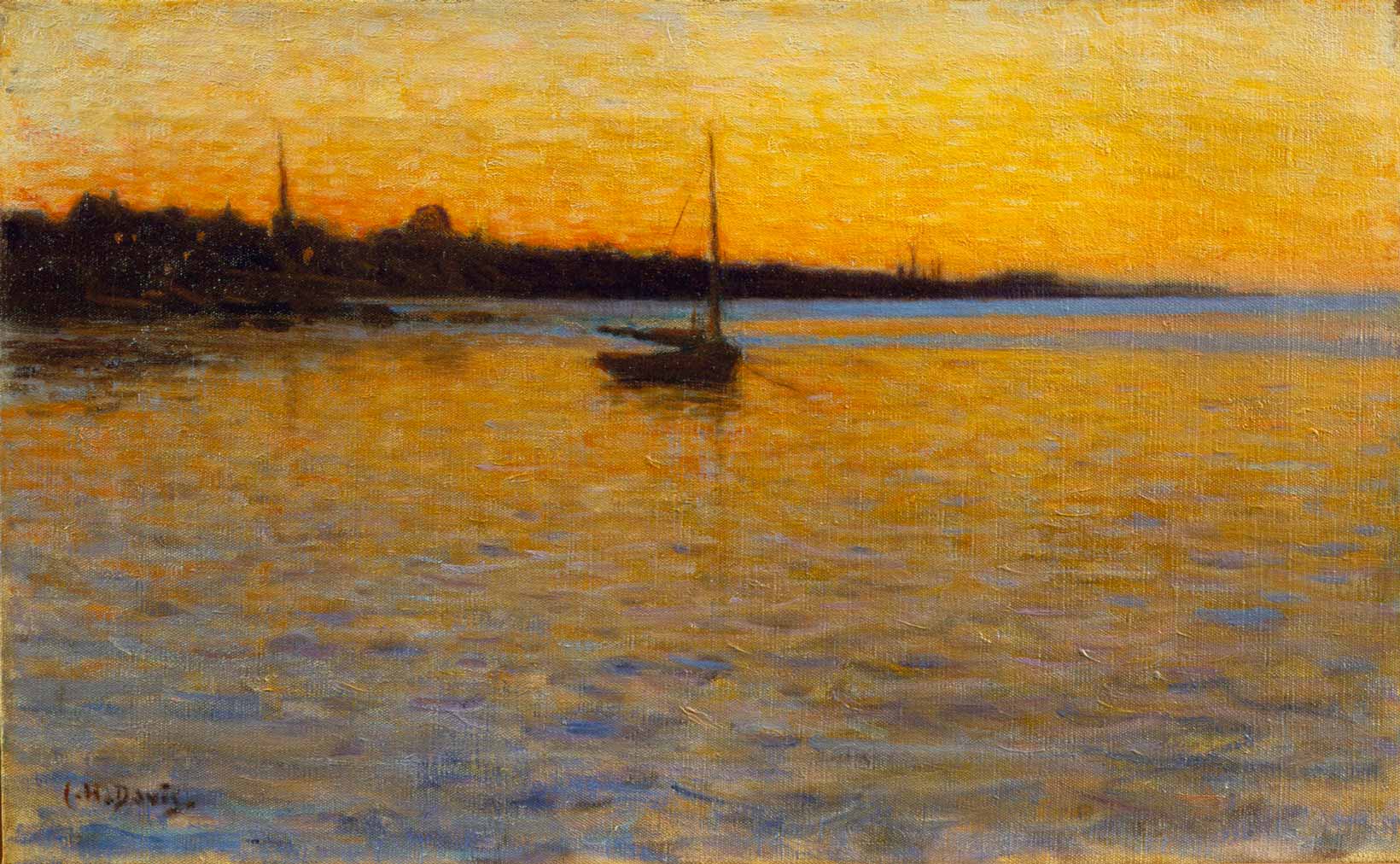

Broken Color or Broken Brushstrokes

The term “impressionism” was first coined to describe works that appeared sketchy and unfinished. Impressionists rejected the highly finished surfaces of academic painting of the time to create a visual language of bright, rapidly applied color to capture light and atmosphere. Impressionist painters developed a way of applying pigment that has been called “broken color” or “broken brushstrokes.”

The paint is applied in mosaic-like patches which creates a rough irregular surface texture. In this work by Childe Hassam, the painter fragments color into small units of flickering touches. For example, Hassam uses this microstructure of small strokes of color to depict the beauty of the chromatic vibrations found overlooking the marshes of a tidal river. He varies the size of his strokes to create a sense of movement and depth as the eye moves about the canvas.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935)

Late Afternoon (Sunset), 1903

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Krieble

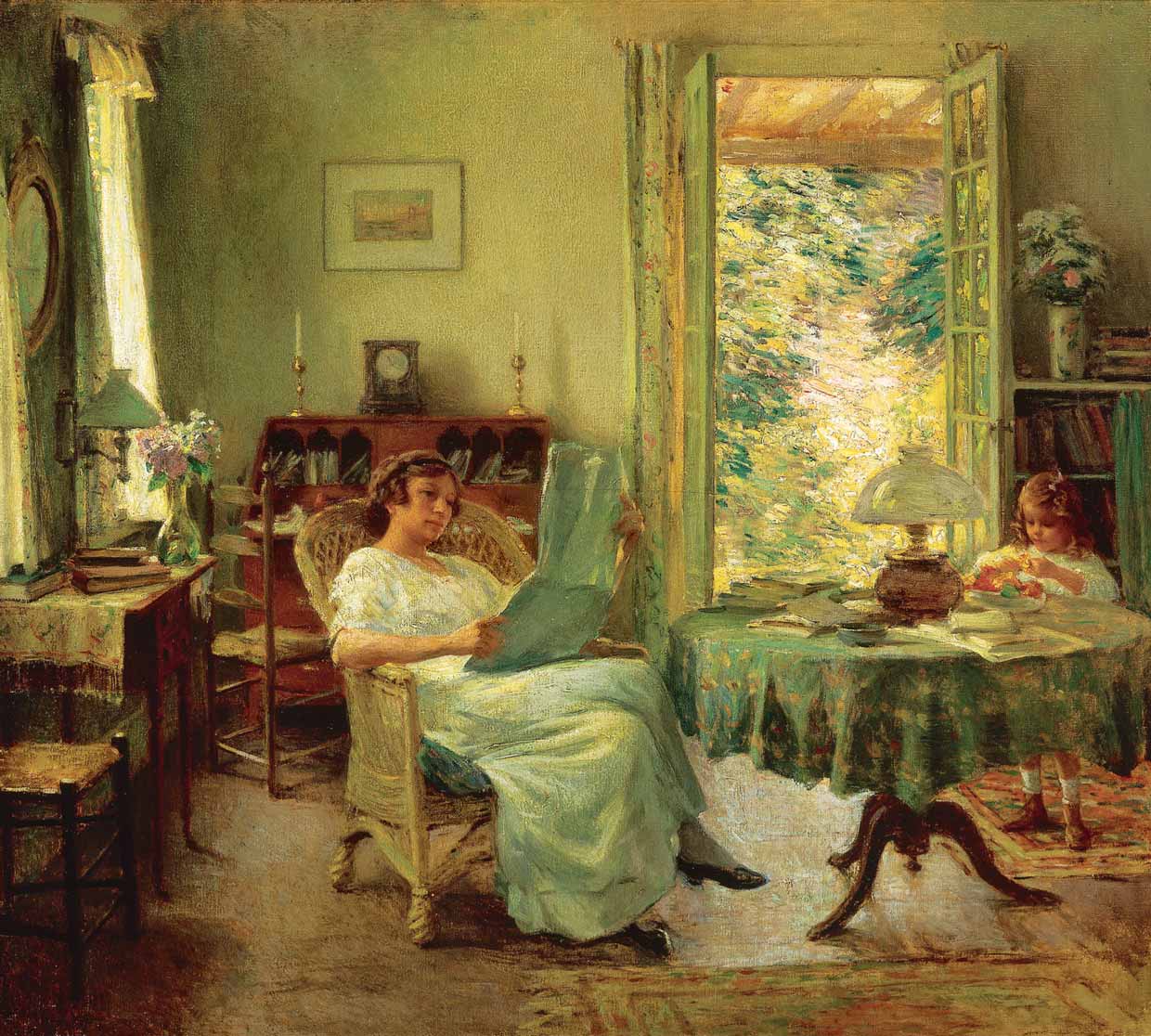

Use of Impasto (or Thick Paint)

Impressionists broke with the notion of academic finish by which paintings appear to have a flat or smooth surface. In an Impressionist canvas, paint is applied in thick raised strokes which is called impasto. Through using thick brushwork an artist can create a roughened uneven texture that often mimics the texture of the subjects as well as captures and reflects light. In this painting, Willard Metcalf paints the interior employing a more traditional approach. Figures and objects are tightly rendered and the paint is smooth and flat. Through open door, however, Metcalf employs a thicker handling of paint. In so doing, he conveys the multitude of color, form, and wild textures found in the garden.

Willard Metcalf (1858-1925)

Summer at Hadlyme, 1914

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Henriette Metcalf

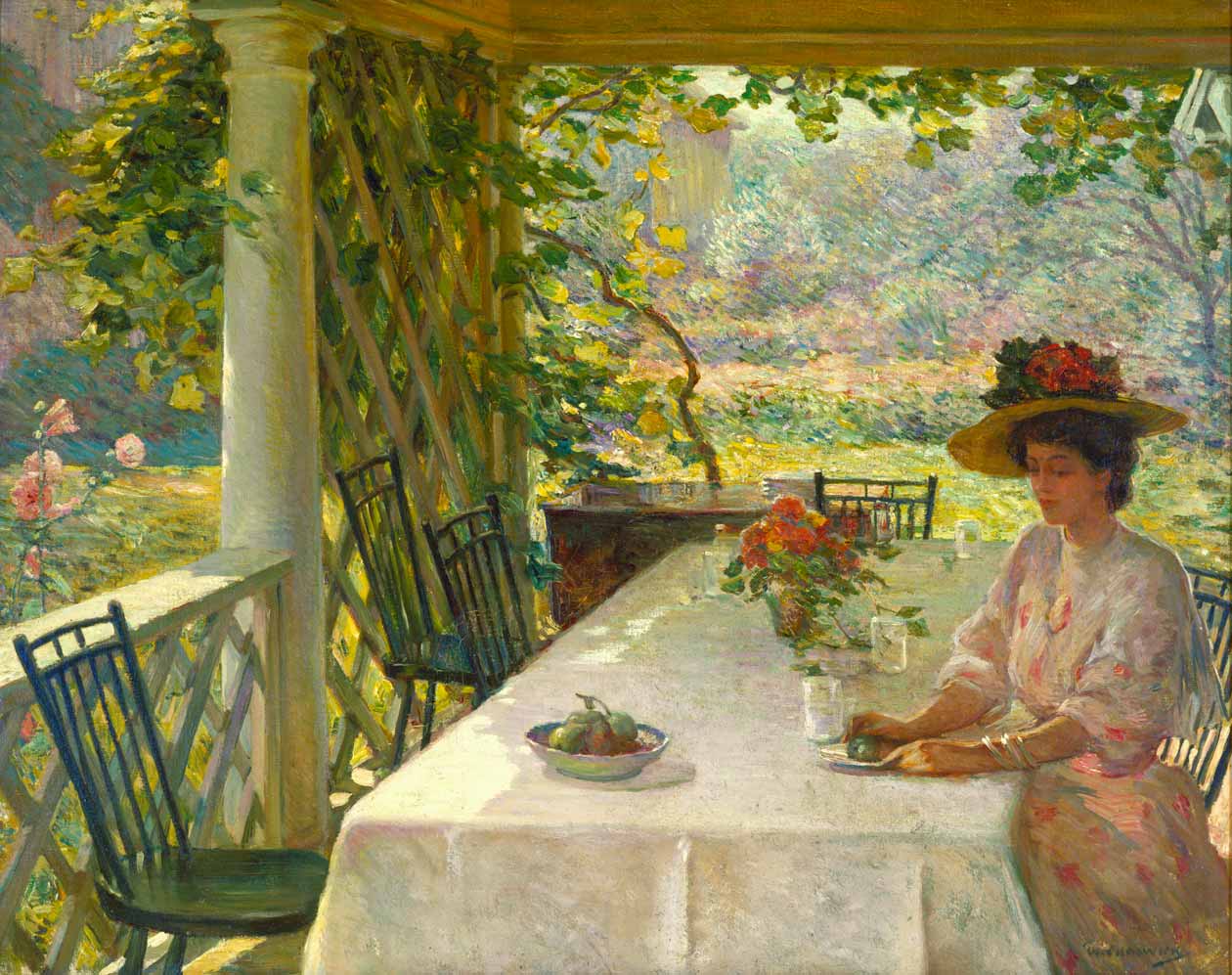

Subject Matter

The subject matter of Impressionism is often casual, everyday life, captured with an immediacy enhanced by transient effects of light and atmosphere. In this work, William Chadwick depicts the play of light and shade upon the Griswold side porch. Other American painters turned to subjects that seemed in keeping with the traditional icons of old New England. Many found inspiration in rural scenes, weathered barns, timber bridges, gardens and old homes while others depicted meandering tidal estuaries, rocky ledges, wooded uplands, and open pastures. In this painting, Chadwick shows a woman at leisure, seemingly lost in reverie, on the side porch of the Griswold House. You can see the old barns and lush old fashioned gardens in the distance.

William Chadwick (1879-1962)

On the Piazza, c. 1908

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs Elizabeth Chadwick O’Connell

High Horizontal Line

Impressionist painters employed a wide range of compositional devices in their work. One of them was the use of a high horizon line that often creates a plunging perspective. Here, the house sits at the top of the canvas and the bottom half is filled with the gardens and pathway.

Matilda Browne (1869-1947)

In Voorhees’ Garden, 1914

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Insurance Company

Photographic Influence

Photography made its appearance in the early nineteenth century, at a time when scientists, philosophers and artists were intent on acquiring an objective and positive knowledge of reality. Photography exerted a powerful influence on the visual arts. Its ability to create a likeness had an immediate effect on portrait painters, but its influence soon spread to landscape artists.

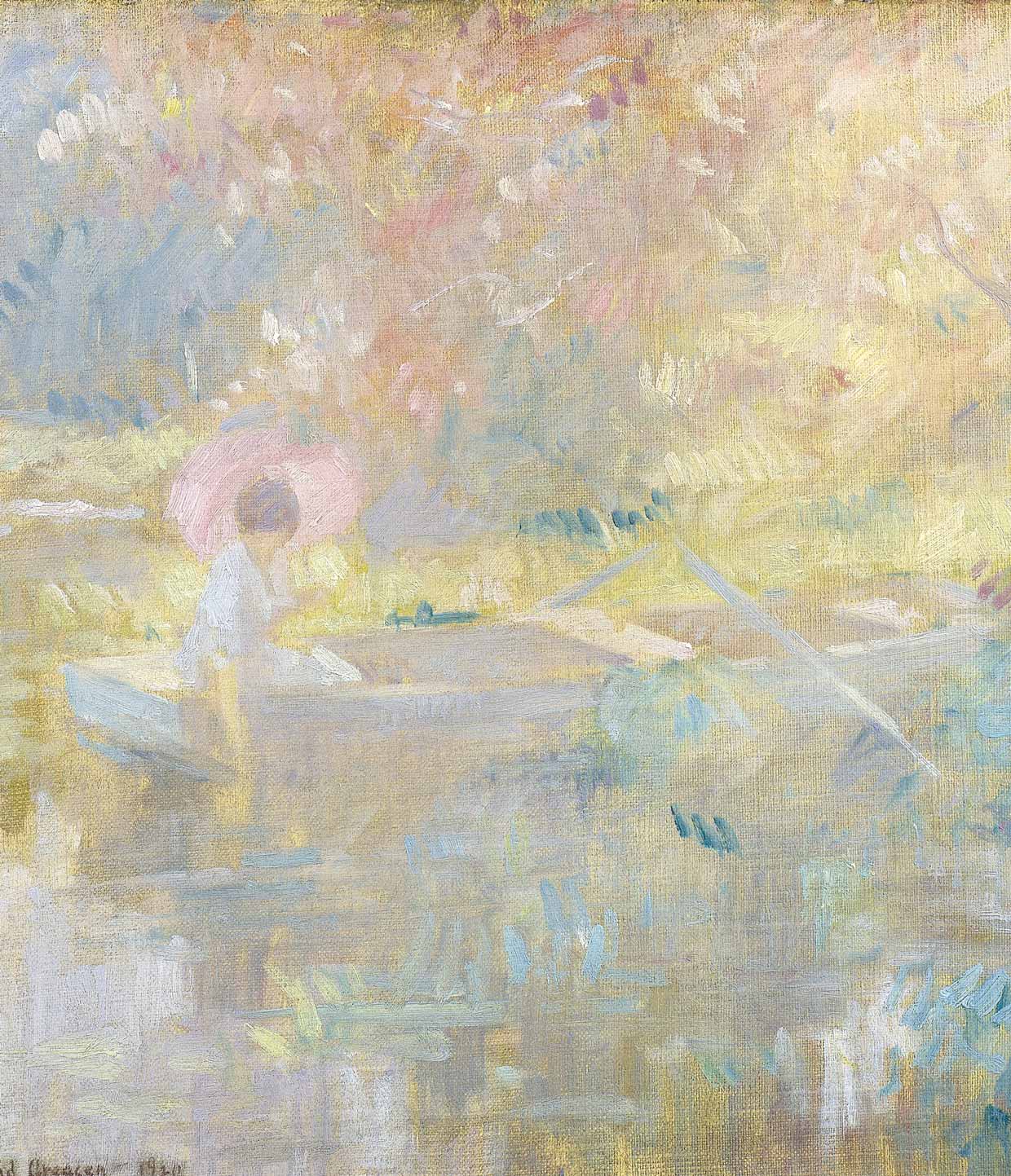

By the time of the Impressionists, technical advances had led to the development of the snapshot camera. Blurrings, unusual juxtapositions and the accidental cropping off of figures in snapshots created the sense of movement and spontaneity that the Impressionist artists wanted to achieve. Here, Edmund Greacen captures the heat of a summer day by blurring his image and enjoying the play of light and color in the reflections in the water.

Edmund Greacen (1876-1949)

The Lady in the Boat, 1920

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Insurance Company

Influence of Japanese Prints

Japanese woodblock prints were first seen in France in the 1850s and soon became immensely popular. Many of the French and American Impressionists collected these prints. The prints both inspired and confirmed the Impressionists’ own ideas about color and form, revealing a very different approach to composition than that of the Western tradition. Japanese artists combine areas of solid color with stylized outlines, emphasizing the surface pattern of the print rather than the illusion of space beyond the picture plan. While European artists created a sense of space and depth using perspective, Japanese printmakers implied spatial relationship by placing one object behind another in overlapping planes.

In his depiction of Bow Bridge, a local subject of that crossed the river behind Miss Florence’s Hoffman demonstrates his knowledge of Japanese prints. His rather stylized treatment of this subject increasing the arch of the timber bridge and his emphasis upon pattern call to mind Japanese artist Hiroshige.

Harry Hoffman (1874-1966)

Bridging the Lieutenant, c. 1906

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Morris Joseloff

Painted "En Plein Air"

The rise of plein-air painting, or painting out-of-doors, is a phenomenon closely connected with Impressionism. The invention of collapsible metal tubes in the 1840s allowed long-term storage and transport of oil paints, making extended outdoor oil-painting trips much more feasible. Until then, oil paints were stored in little pouches made from pigs’ bladders that the painter pierced with a tack to squeeze out the paint.

Artists had sketched in the open air before and it was not new to art in the 19th century. But what was new was method of completing a work directly in the open air, and also in the recognition that such works were equal or superior to “composed” landscape and figure subjects, conceived and executed in the studio. Often, work completed out of doors was on wood panels that fit securely into an artist’s paint box for safe travel.