Exhibitions

An American Place: The Art Colony at Old Lyme

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm.

Ongoing Exhibition Florence Griswold House second floor gallery

During the first two decades of the 20th century, the village of Old Lyme, Connecticut was the setting for one of the largest and most significant art colonies in America.

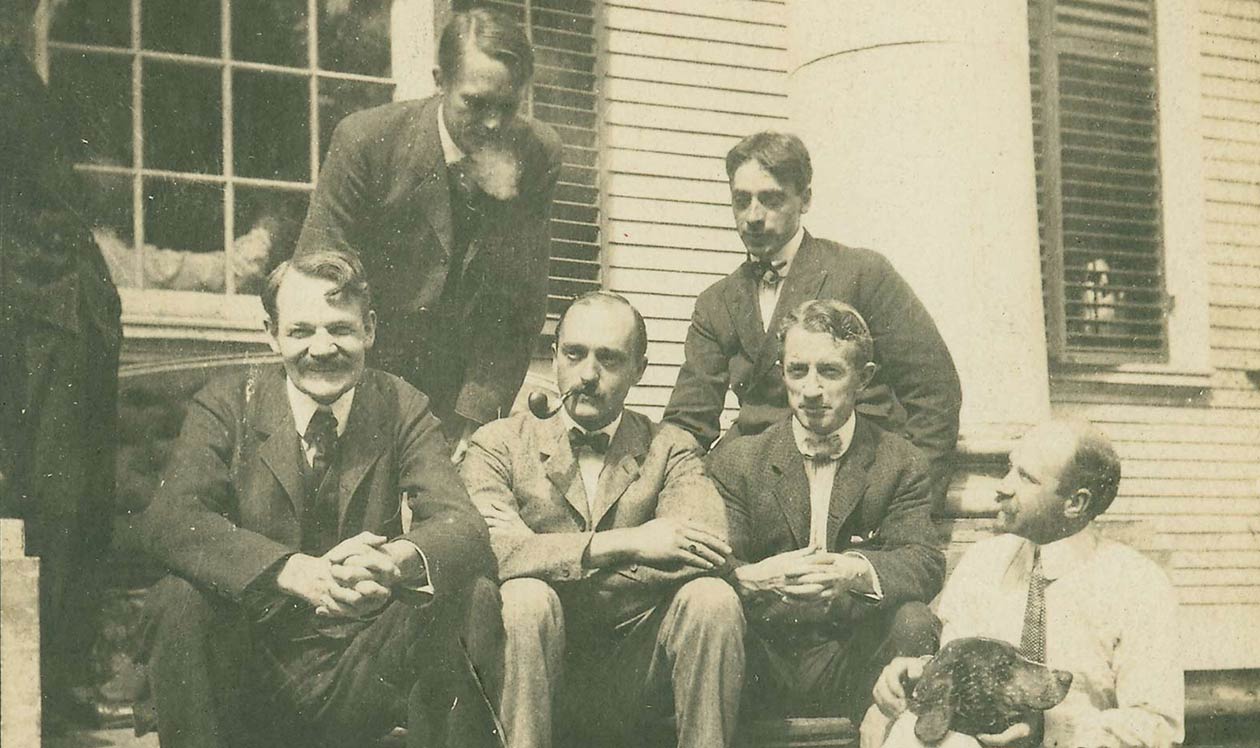

Centered in the boardinghouse of Miss Florence Griswold, the colony attracted many leading artists – Henry Ward Ranger, Childe Hassam, and Willard Metcalf among them – who were in the vanguard of the Tonalist and Impressionist movements. Drawn to Old Lyme by its natural beauty, they discovered an “old” New England setting that was, as one observer noted, “expressive of the quiet dignity of other days.”

Here was a country retreat for artists where, in Metcalf’s words, “every day is so in line with work.” Interacting with each other and with the community, the more than 200 artists of the colony produced an impressive body of work, which achieved renown in its day and still calls attention to the enduring qualities of the rural New England setting.

The Landscape of Lyme

“The variety in the landscape would drive an artist to distraction. It is a singular mixture of the wild and the tame, of the austere and the cheerful.” – A visitor to Lyme in 1876

Artists who came to Connecticut in significant numbers at the turn of the 20th century found a landscape that was intimate, rural, and soothing at a time when America was becoming urban, industrial, and restive. The themes they explored were those first seen in the aftermath of the Civil War, when an intense longing for order and stability led artists to favor quiet, peaceful views over awesome wilderness vistas. Connecticut, with its gentle, cultivated landscape and pre-Revolutionary history, became for the first time a significant place for the making of the nation’s landscape art.

The American Impressionist Wilson Henry Irvine loved to paint outdoors, especially, as he noted, “when there’s a kind of haze beauty in the air.” Late Summer captures the heavy, moist atmosphere of this season in Connecticut.

Located where the Connecticut River flows into Long Island Sound, Old Lyme was particularly ripe for discovery by artists. A thriving and sophisticated maritime town in the first half of the 19th century, it had gradually reverted to an economy based on farming and cottage industry. Turning inward, Old Lyme became a largely forgotten byway, clinging to its glorious past. Its one constant and defining feature was an impressively varied landscape that combined meadows, marshes, ancient trees, and winding rivers with old New England buildings, homely dirt roads, and well-worked farmlands. A landscape steeped in historical associations and nostalgia, Old Lyme was, as one of the artists exclaimed, a place “only waiting to be painted.”

Henry Ward Ranger and His Tonalist Circle

“The school of Lyme is a group of painters brought together over the idea of tonality.” – Artist Henry Rankin Poore, 1903

From its beginnings, the Lyme Art Colony was shaped by a strong group identity. Calling themselves the “School of Lyme,” the first artists who came at the urging of the colony’s founder, Henry Ward Ranger, believed they were forming a new school of painting in America. United by their shared interest in painting rural life with great sensitivity and personal feeling, these artists were identified as Tonalists. As a style, Tonalism flourished in America from the 1880s to the early 1900s and is characterized by the use of harmonious colors and delicate effects of light to create vague, suggestive moods.

The earlier Barbizon tradition, in both its French and Dutch manifestations, was a powerful legacy. Like Corot and Rousseau before them, these artists of Lyme sought to attain a synthesis of realism, based upon what they saw, with a subjective interpretation of nature, based upon what they felt. Old Lyme’s landscape, worked by generations of farmers, stirred deep feelings in the minds of these painters and, not coincidentally, their patrons. A lingering romanticism can be found in their poetic depictions of New England rural life. As Ranger put it, “I would like to get into my pictures of this region a little of the love I feel for those who made it.”

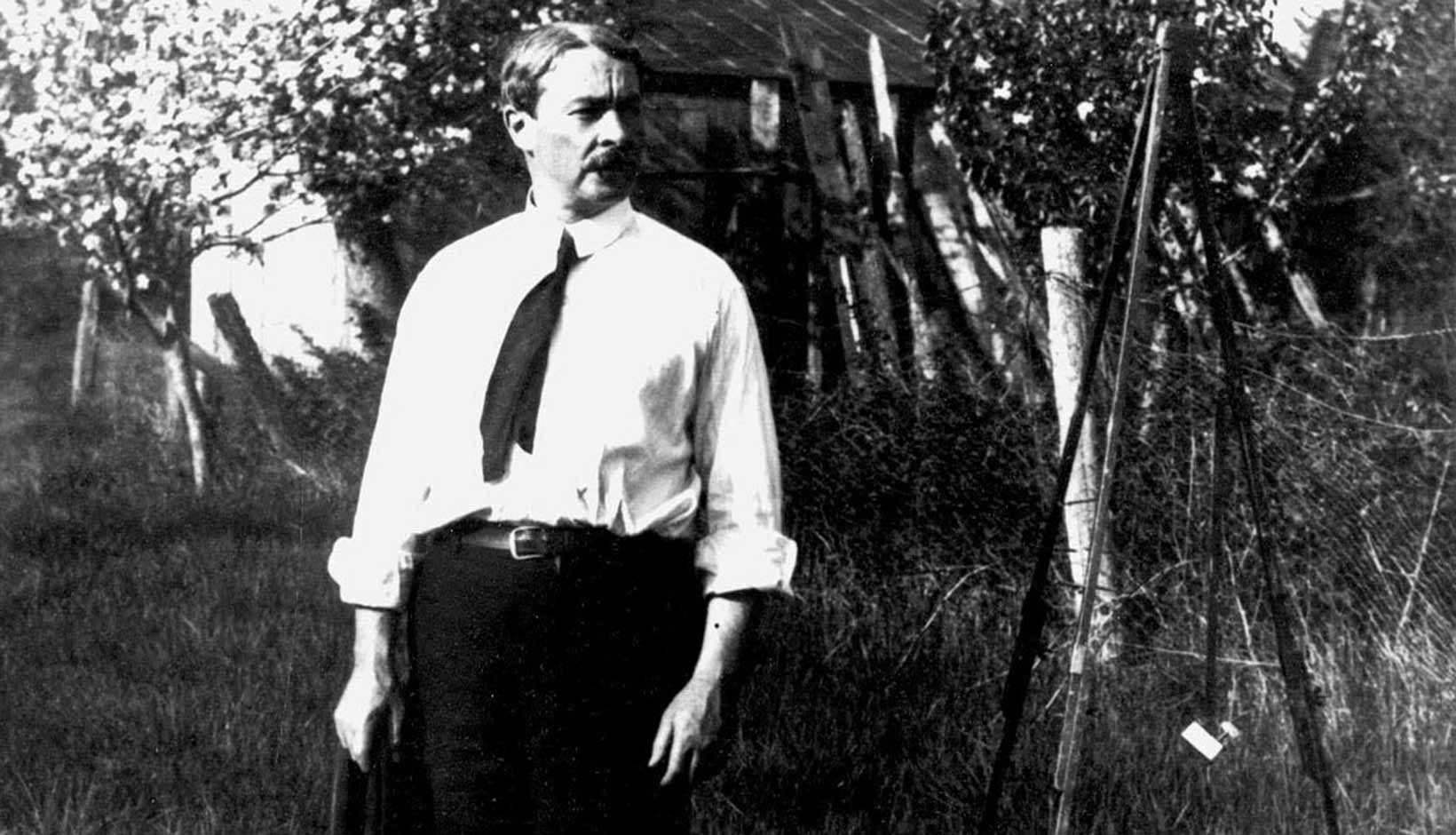

Outdoor sketching was a nearly universal working method for the artists of the Lyme Art Colony. The invention of collapsible metal tubes in the 1840s allowed for long-term storage of oil paints, making extended outdoor painting possible. This technological advance would transform the practice of painting in this country. Before then, oil pigments were stored in fragile glass syringes or pouches made from pig bladders and were used principally in the studio. Often outfitted in country tweeds, knickers, and backpacks, the Old Lyme artists carried paint boxes filled with brushes, palettes, tubes of paint, and small canvas boards out into the open countryside to paint directly from nature. Using portable easels, and perhaps a canvas stool and sun umbrella, they painted under endlessly varying conditions and endured the distractions of both mosquitoes and curious onlookers.

The objectives of outdoor sketching varied from artist to artist. For the Impressionist, it could yield a finished canvas, or one nearly so to be completed in the studio. For the Tonalist, it was primarily the gathering of visual information in a sketchbook or on an oil sketch. “The object of study and sketching out of doors is to fill the memory with facts,” remarked Tonalist Bruce Crane. But for virtually all of the Lyme painters the oil sketch, usually painted on a wood panel or canvas board no larger than 12 by 16 inches, was prized for its spontaneity and freshness. Some were exchanged between artists as tokens of friendship or developed into larger works. Others were sold by Miss Florence from her downstairs center hallway. From the very beginning, painted sketches were shown along with larger oils in the colony’s local exhibitions and were popular with many patrons as affordable, and sometimes preferable, examples of an artist’s work.

Childe Hassam and the American Impressionists

“You should see [my studio] here, just the place for high thinking and low living.” – Childe Hassam to J. Alden Weir, 1906

Against the stimulating artistic backdrop of the Griswold House, the Lyme Art Colony fostered the testing of new ideas and subjects in its art. With Childe Hassam’s arrival in Old Lyme in 1903, followed shortly thereafter by fellow Impressionist Willard Metcalf in 1905, the colony’s stylistic identity shifted from Tonalism to Impressionism. Frequent reappearances in Lyme by these two proponents of the new style drew scores of like-minded artists to the colony, contributing to its identification as the most famous art colony in America. Old Lyme’s reputation was significantly enhanced by the success that Hassam, Metcalf, and others had with pictures of local subjects in national and international exhibitions. One newspaper noted in 1907 that this success “made Lyme sound like Standard Oil, and with no less enthusiasm than the gold hunters of ’49, the picture makers have chosen Lyme as the place to swarm.”

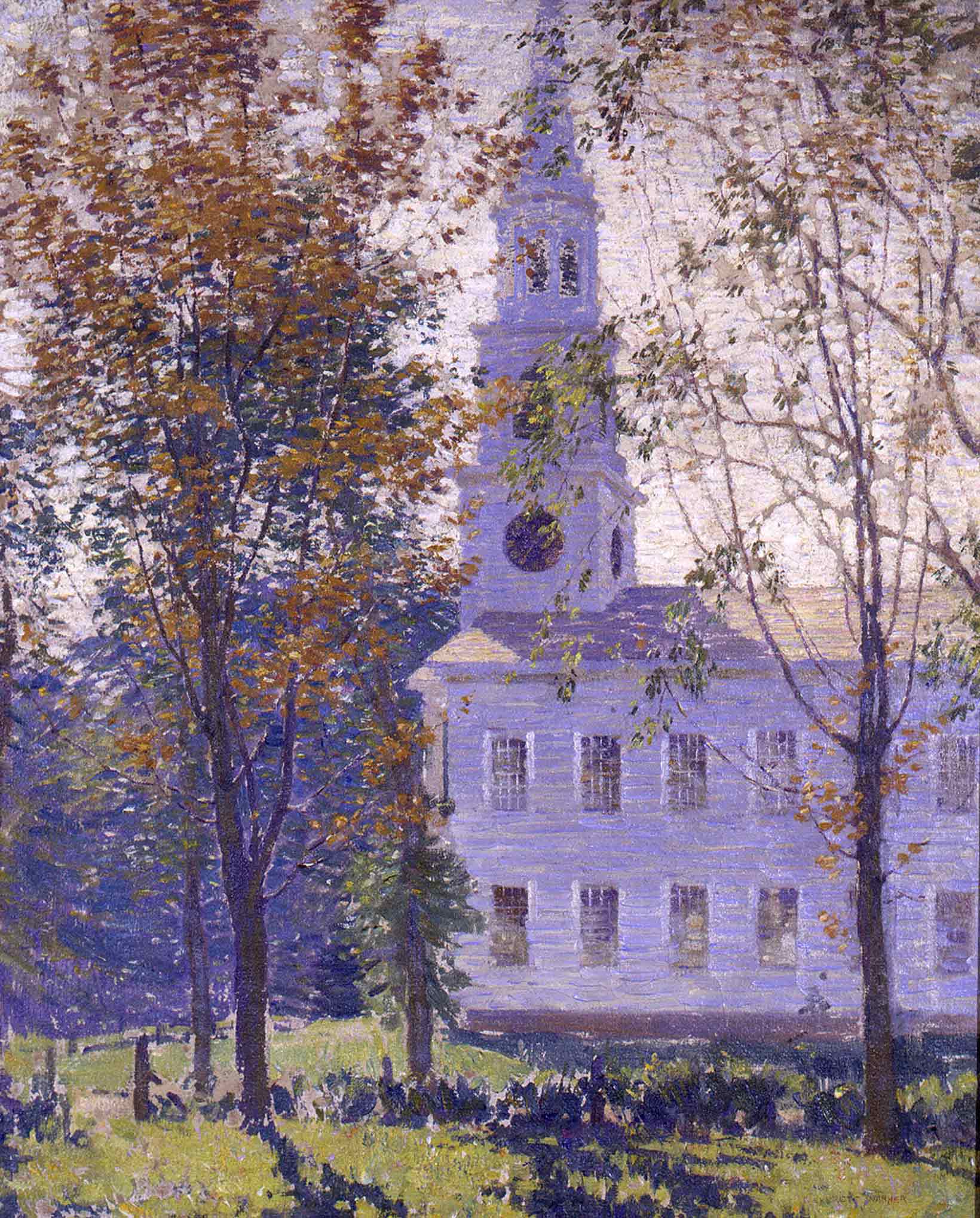

Although their art was informed and inspired by the works of the French Impressionists, especially that of Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir, the American Impressionists adapted their style to home ground. They freely imported the characteristics of what was once considered a radical style – the use of high-key colors and broken brushstrokes applied directly to the canvas – and adapted it to their own designs. Rather than focusing on the modernity of the city as the French had done, the American Impressionists presented a fresh look at rural New England at a time when life in this country was fraught with great change and uncertainty. Just when America was poised on the edge of modernity, these painters looked backward to Old Lyme’s Colonial houses, churches, old-fashioned gardens, and well-worn landscape as evidence of a stable, timeless order far removed from the dazzle of the ephemeral.

Guy was the son of the American Barbizon painter Carleton Wiggins, and he shared his father’s preference for painting in and around Old Lyme. The son, however, left images of sheep and cows to the father and looked instead at the character of the area’s landscape and shoreline. Seascape is probably a view of Mystic or Noank, Connecticut, two of the many shoreline villages that he explored, especially early in his career. This is probably an early work, since at some point he dropped his middle initial from his signature.