Families

Stitching it Together

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm.

An Online Learner's Guide

This learner’s guide is an online introduction to the subject of schoolgirl embroidery and provides definitions of the various types of needlework, ranging from samplers to silk embroideries, a list of locations of the schools where needlework was taught, a timeline that places the works in the exhibition into the context of Connecticut and American history, and lastly, a series of pre- and post- visit classroom activities aligned with the goals of Connecticut State Standards for history curriculum. This online learner’s guide was made possible through generous support of the Coby Foundation, Ltd., and the Connecticut Humanities Council.

Samplers

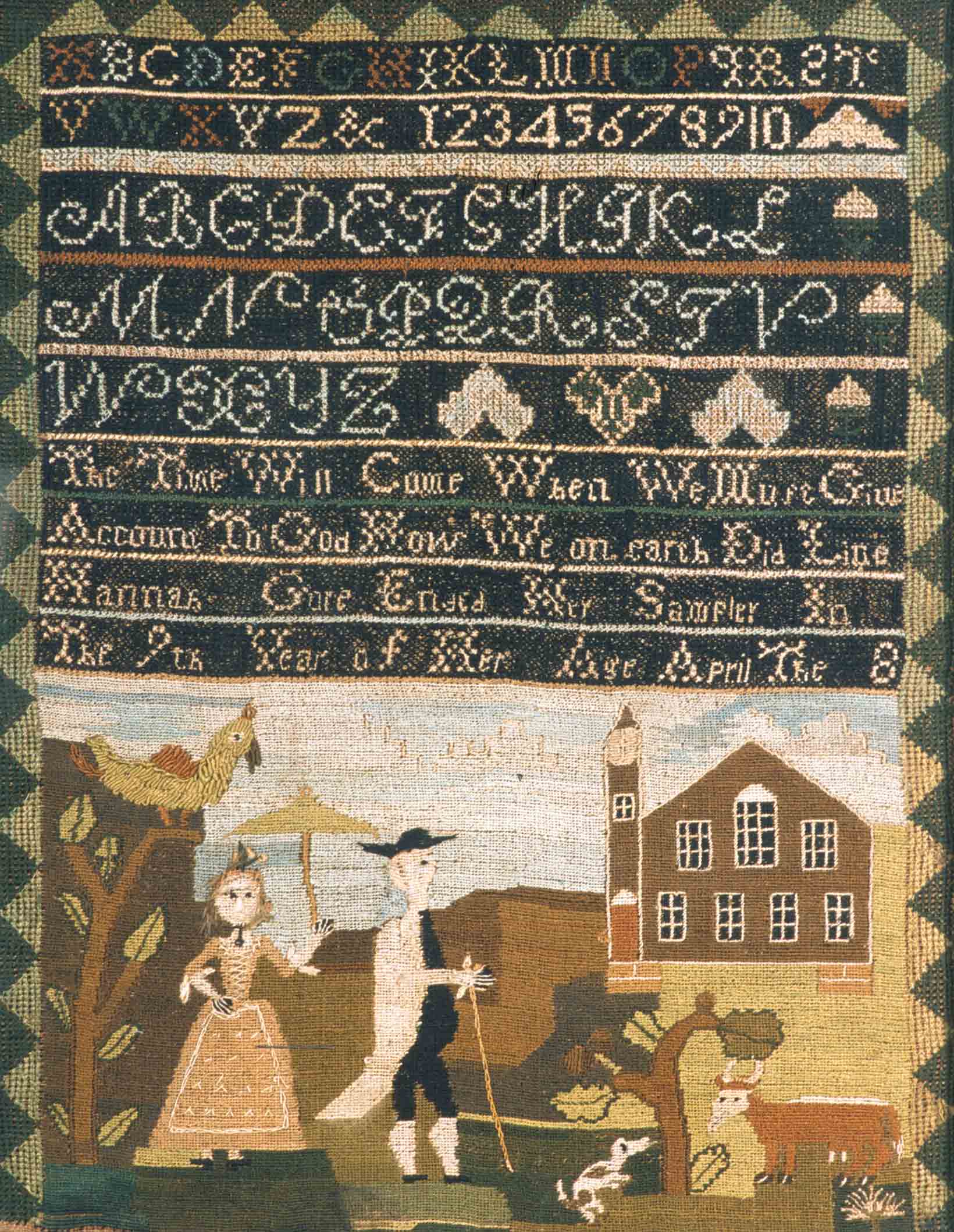

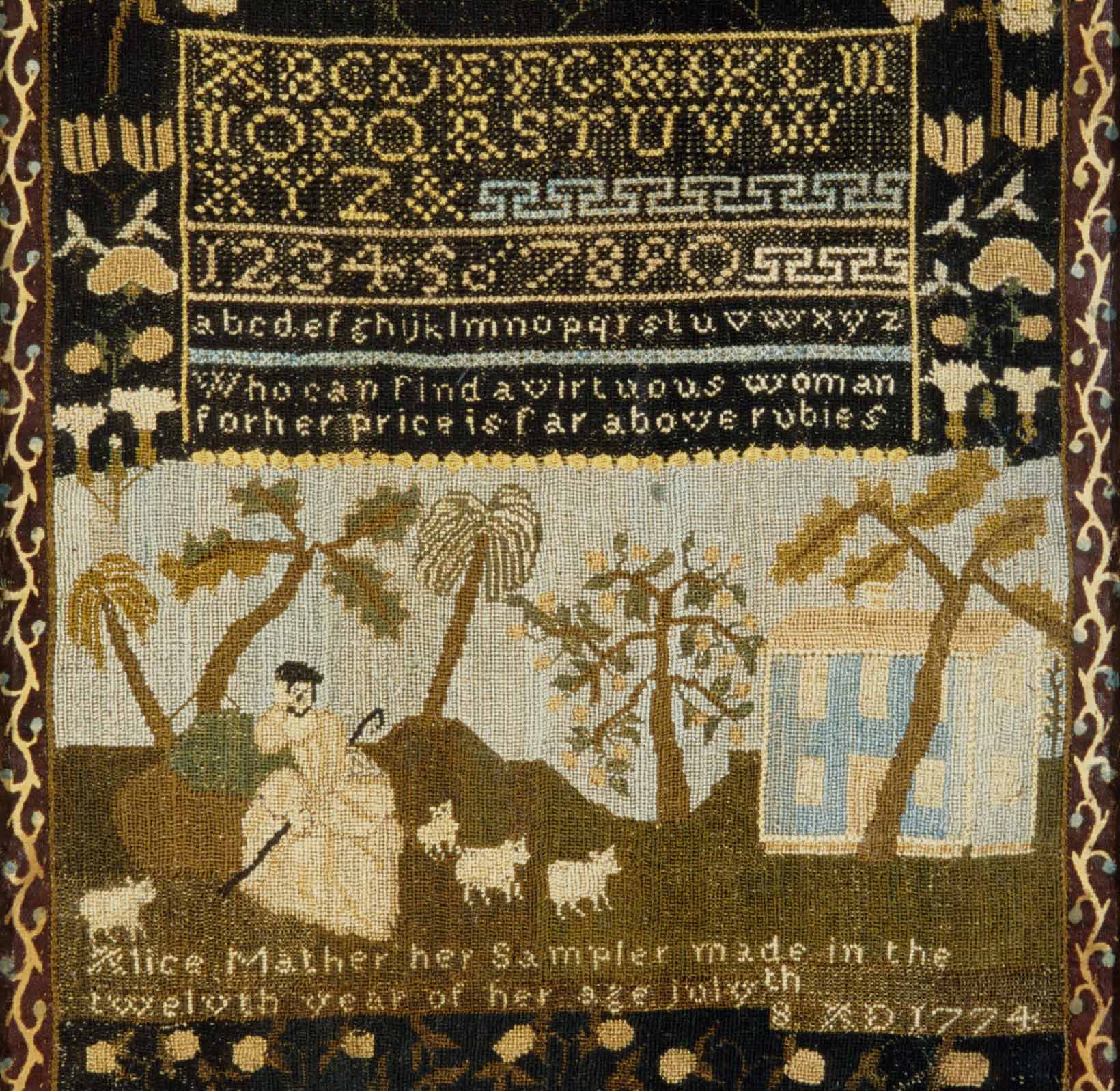

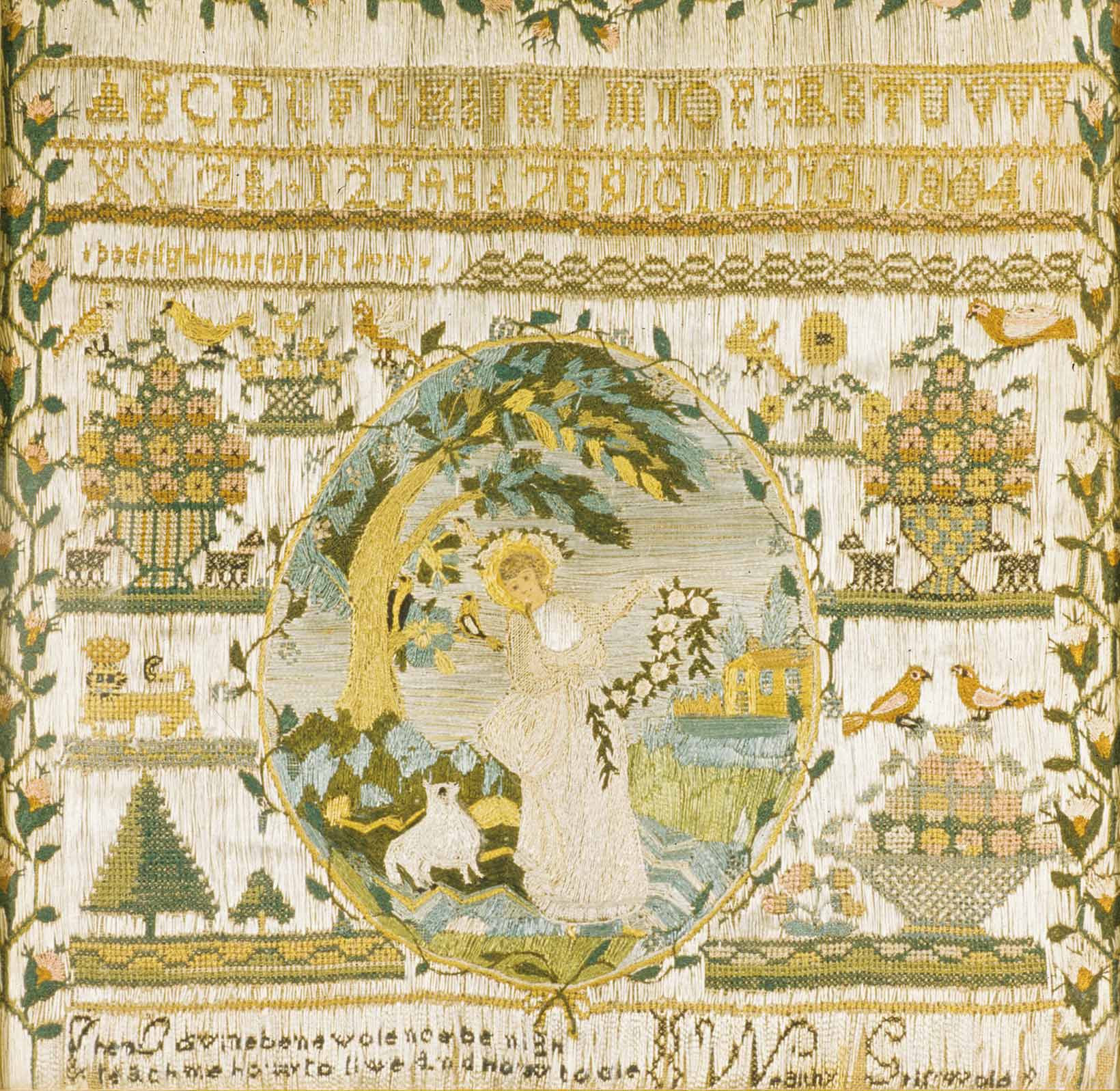

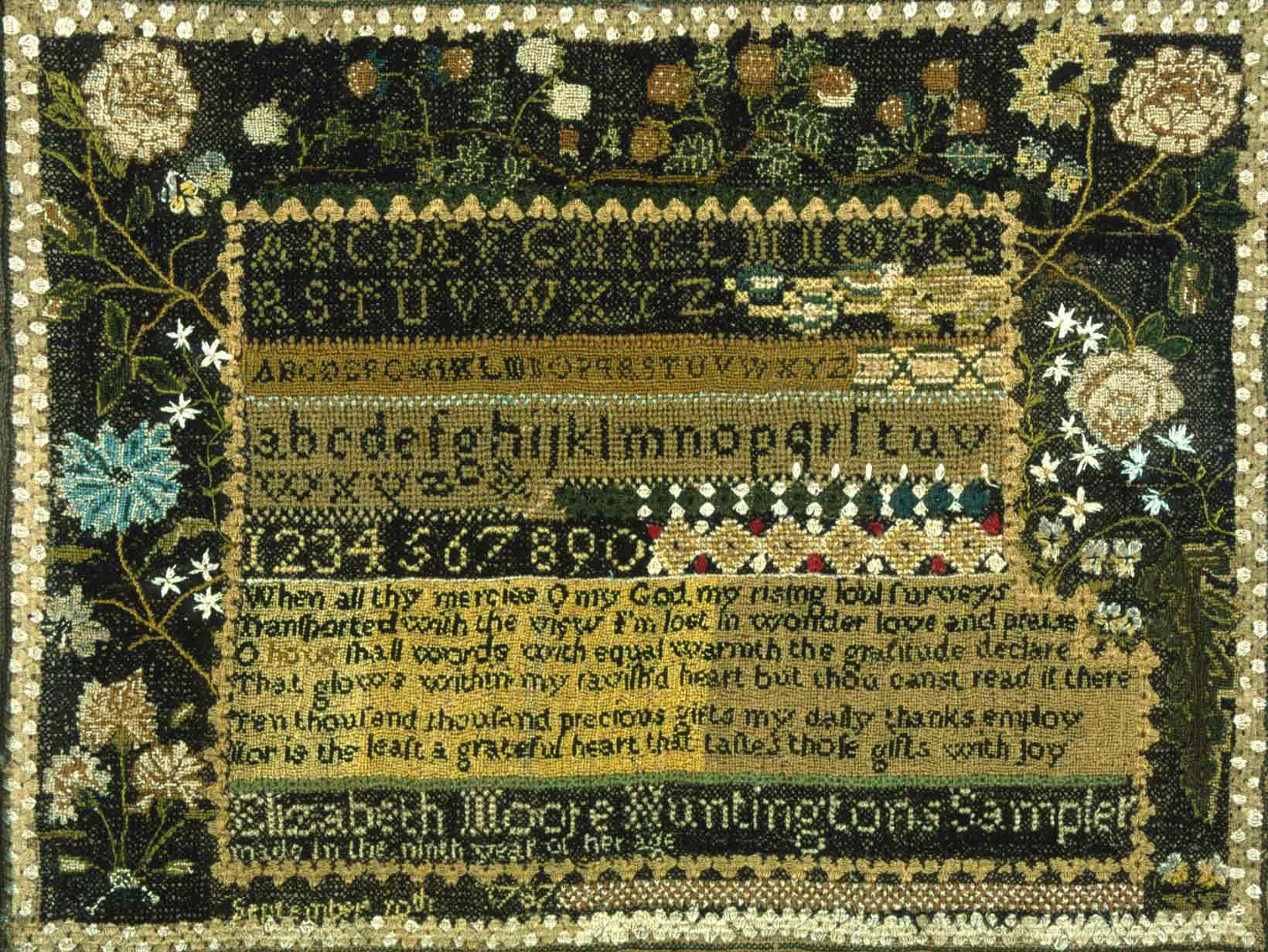

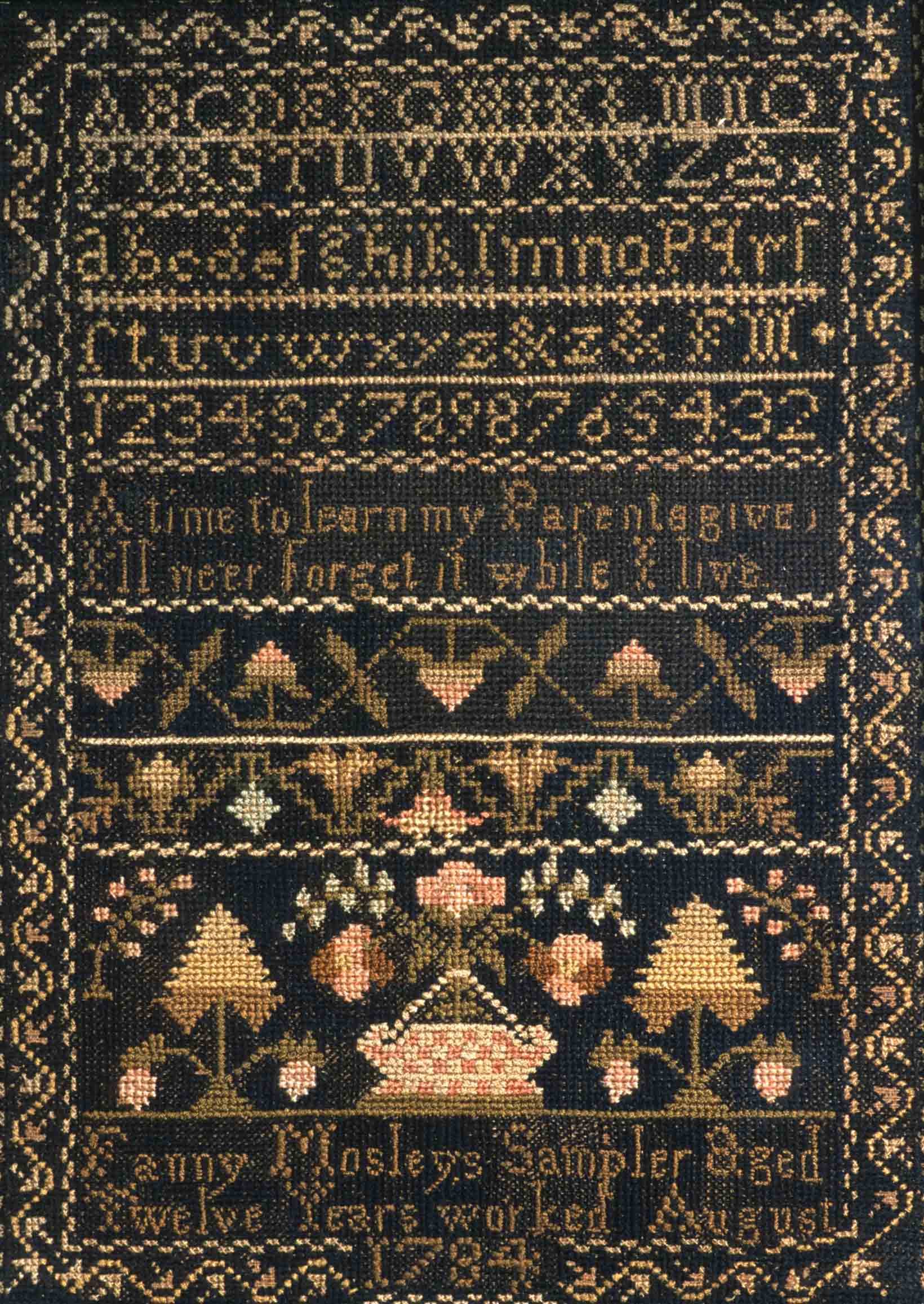

Samplers began as a way to record types of stitches as well as shapes and patterns to be used when sewing. A sampler is a piece of needlework using silk thread on a linen cloth that often features the alphabet in both upper and lower case letters as well as numerals.

Early samplers were often long and narrow and would be rolled up and kept in a woman’s workbasket for easy reference. At the beginning of the 18th century, samplers began to evolve into shorter, wider shapes. These newer samplers might include a small scene in addition to the traditional letters and numbers. As samplers became more decorative, they were often framed to be hung on the wall to be enjoyed and appreciated as works of art. Indeed, sophisticated samplers became a cherished centerpiece displayed in the most formal room in the house, usually a parlor. Parents, proud of their daughters’ accomplishments, used samplers to beautify their home while encouraging suitors or other visitors to contemplate the family’s wealth’s and culture.

Although it is easy to envision the nostalgic scene of young girls dutifully stitching by flickering candlelight surrounded by friends and family, most samplers were made at private academies, often quite expensive boarding or day schools, under the watchful eye of the female instructor who guided the layout and design and taught the various stitches. Over the course of their education, girls undertook progressively more complex and difficult needlework. Beginning before the age of ten with elementary samplers worked on linen athey gradually developed a rich repertory of stitching techniques.

Parts of a Sampler

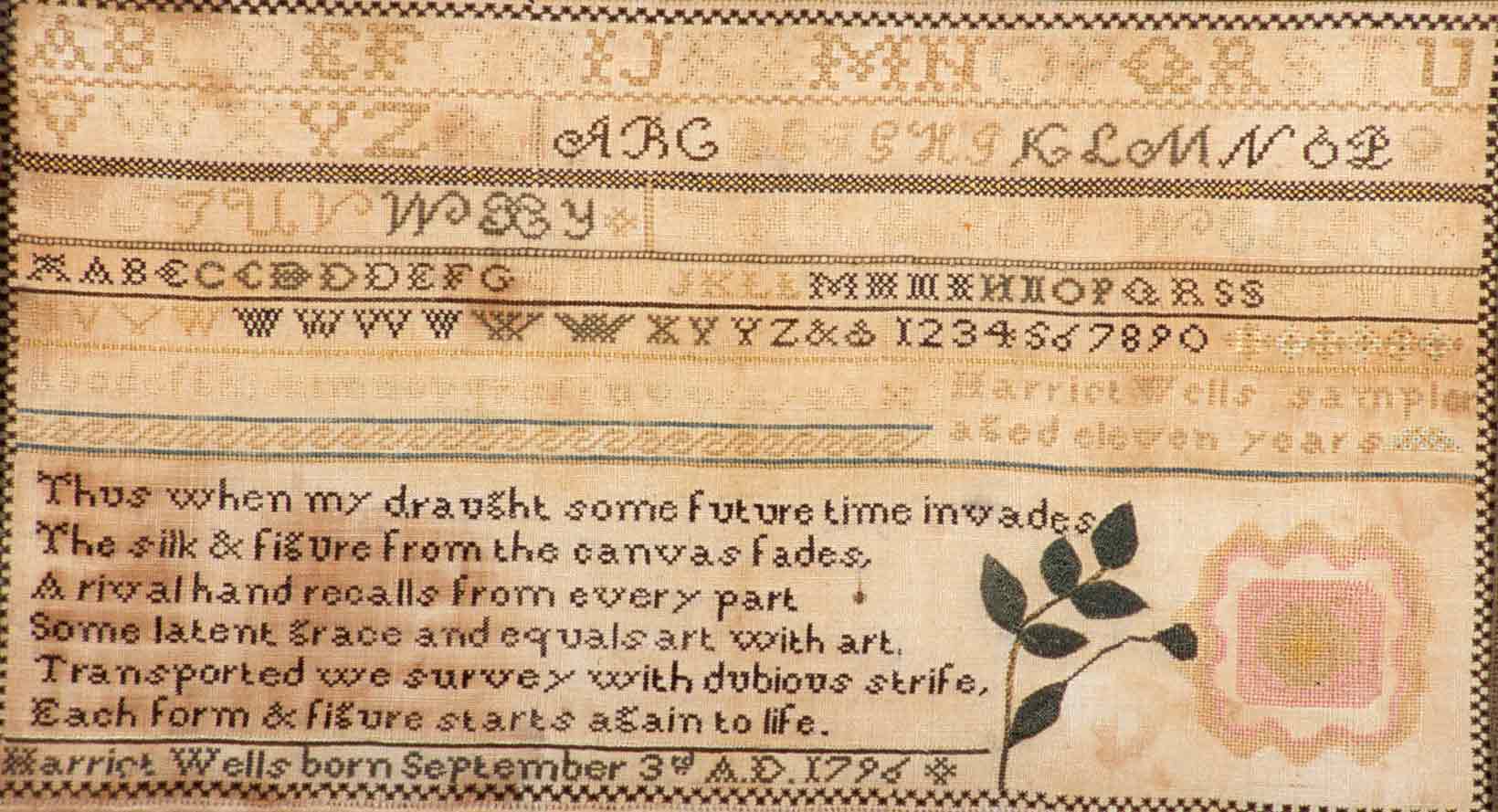

The Alphabet in Upper Case Letters

A stitched alphabet in upper case letters is the most common element of a sampler. This example only includes 25 of the 26 letters because the letter J was not included in the Roman alphabet until about the year 1800. This piece is dated 1774 by the maker, but the missing J would have been an added clue to its creation date. The maker also included an ampersand symbol, &, which is used as an abbreviation for the word “and.” The maker filled out the leftover space with a blue key pattern.

Numbers

This sampler also includes Arabic numerals from 1 to 9 with a zero at the end. With these shapes mastered, the young girl could stitch any number she liked with her sampler as a guide.

The Alphabet in Lower Case Letter

A second stitched alphabet in lower case letters is also included on this sampler. Here the letters are sized so as to create a neat row that fits exactly into the composition and requires no decorative key pattern to fill out the empty space. The maker used both upper and lower case letters in her stitched verse below and maker inscription near the bottom revealing her mastery of both forms. Some samplers also include cursive versions of the alphabet.

Famous Quote or Verse

Samplers often include a proverb or uplifting moral phrase. The biblical phrase, “Who can find a virtuous woman for her price is far above rubies” is from the Proverbs 31:10. Phrases from church hymns as well as everyday proverbs were popular sources for the young women’s stitched verse.

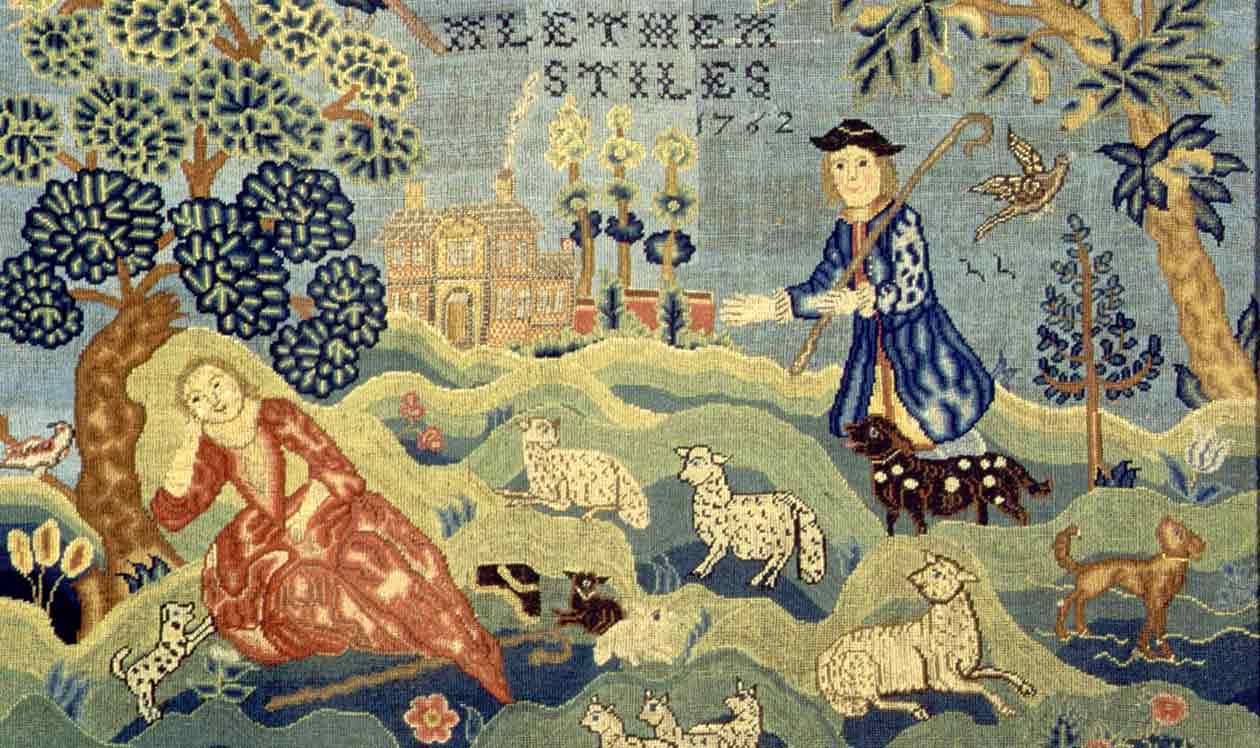

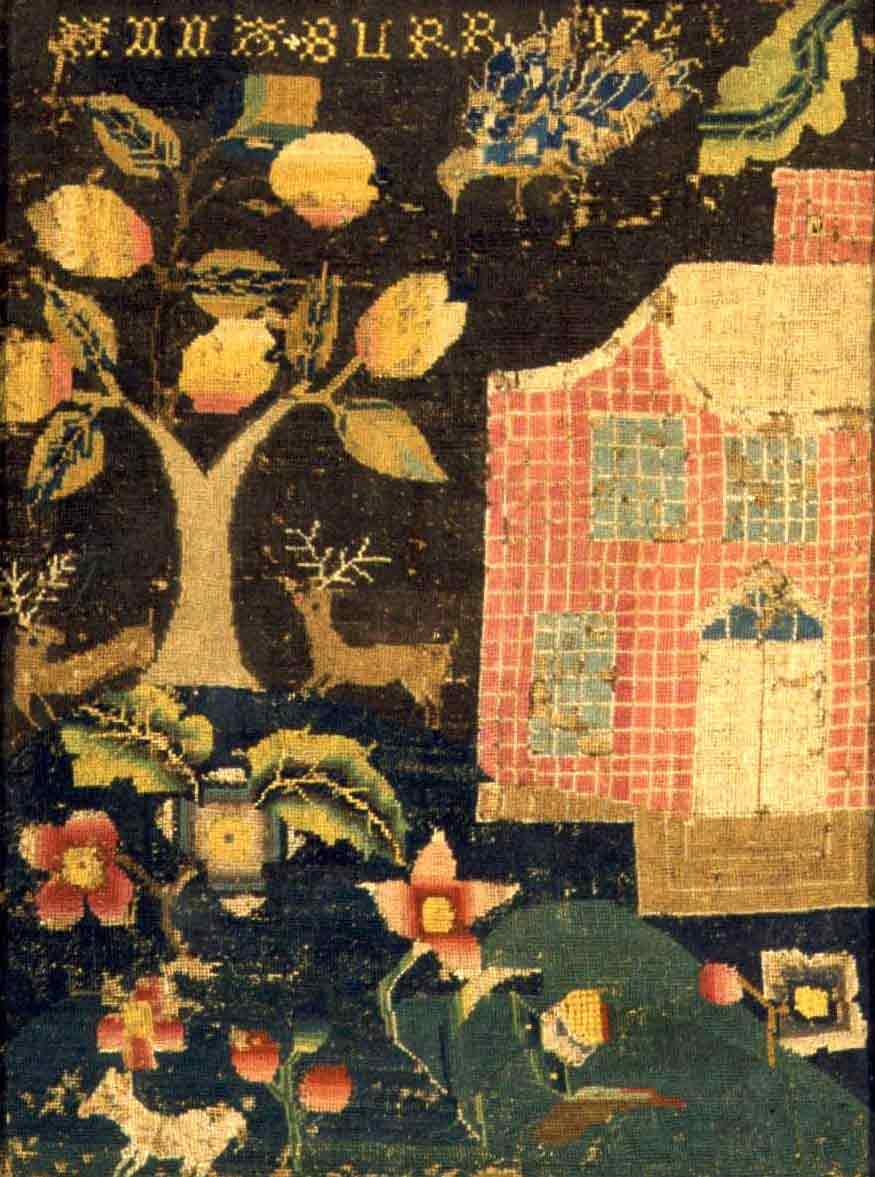

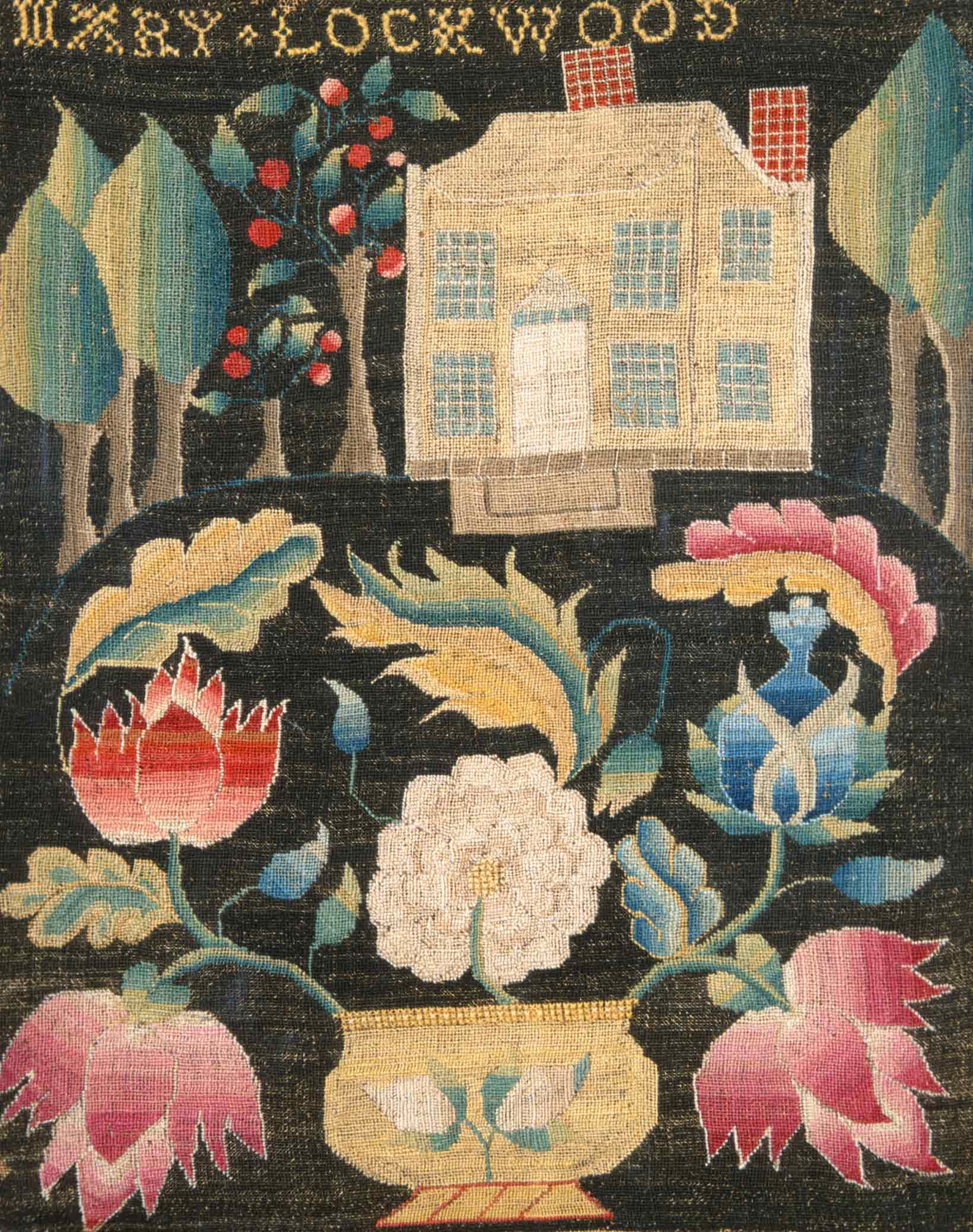

Needlework Picture

As samplers became more elaborate, they would often include a stitched pictorial scene. In this sampler the maker has included a shepherdess holding a shepherd’s crook attending her small flock of sheep. She is shown leaning on one elbow resting under an assortment of trees, some of which look like palm trees which are not native to New England. There is also blue Colonial-style house next to a flowering tree.

The subject matter and stylistic approach of this picture have interesting connections to other sampler designs. The shepherdess motif, for instance, was common in samplers made in and around Boston. Palm trees later became a popular motif in samplers created at the Misses Pattens’ School in Hartford. Lastly, the black background, which was stitched and not based on the color of the linen, was a distinctive design element employed by young women in the area of Norwich, Connecticut.

Maker’s Inscription

It was quite common for the maker of a sampler to include information about themselves within the design of the sampler. Facts like their name, age, and the date the sampler was being worked on, or finished are stitched into the design. From these maker inscriptions, we can learn a great deal about the time and place in which the objects were made.

In this sampler the maker tells us that: “Alice Mather her sampler made in the twelvth year of her age July 8th A.D. 1774.” From this we learn that the sampler was made by 11-year old Alice Mather. She has not had her 12th birthday yet, but is “in” the 12 year of life. She also did not misspell the word “twelfth.” Her use of a “v” rather than an “f” as we do today was correct spelling before 1812. She dates the sampler “July 8th, 1774.”

Additional research tells us that Alice was born in Lyme, Connecticut in 1762. She was the daughter of Dr. Samuel Mather (1742/43-1834) and Alice Ransom (1743-1805) and married Dr. William Ely (1762-1829) of Lyme in 1783. They had four children. Alice died in 1842.

The Border

This sampler features a decorative border around the box containing the alphabet filled with a variety of stitched flowers against a black background. Both the flowers and the black area are created with stitches on a lighter-colored linen. The entire sampler is embellished on all four sides with a chintz fabric.

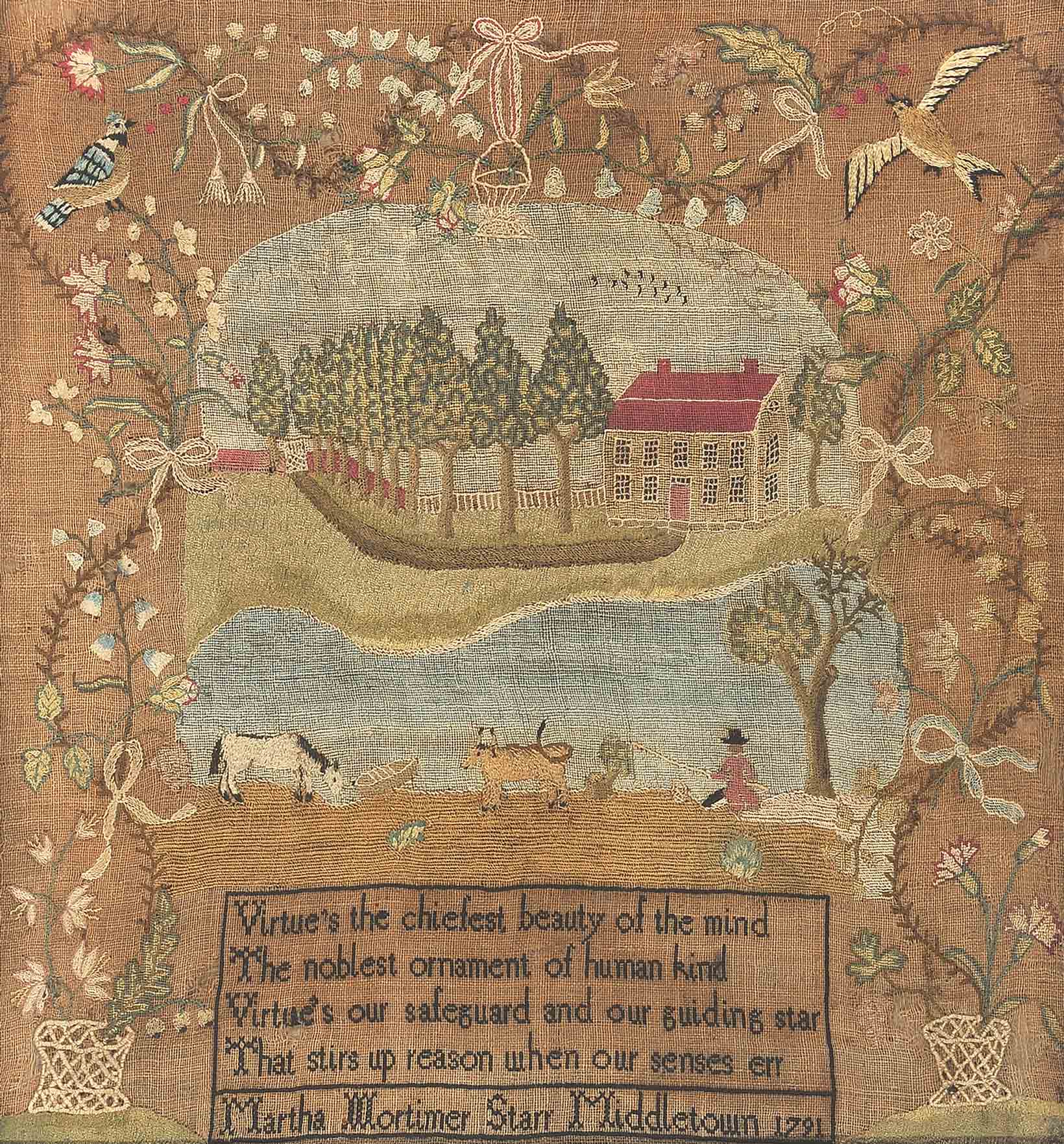

Canvaswork Pictures

Canvaswork pictures often show scenes of daily life with people outdoors in the landscape, reading, talking, or even fishing. The pictures are made by stitching colored silk or wool thread into a linen cloth. The design is first sketched onto the bare cloth and the colors are filled in using needle and thread to make simple stitches. Stitch after stitch the linen gets filled in with color. Imagine painting a picture with tiny dots of color. Each stitch is a dot of color.

Canvaswork pictures often are made with a simple tent stitch. To make a tent stitch, using the horizontal and vertical lines of the woven cloth as a guide, bring the needle up from the back of the linen and cross over the intersection of one warp (vertical) and one weft (horizontal) threads, and then pull the silk thread taut forming a small stitch at a 45-degree angle.

Proudly displayed in a family’s home as an enticement to potential suitors, these pictures revealed a young lady’s mastery of the principles of “politeness”—a concept that encompassed knowledge of religious and literary themes as well as an appreciation for art and music.

This canvaswork was likely stitched by either Lucretia or Katherine Chandler of Woodstock, Connecticut. It is known that at least Katherine attended a private school in Boston where she trained as a needleworker.

Parts of the Chandler Canvaswork

Couples in Conversation

Two elegantly dressed couples are engrossed in conversation. The couple on the left is sitting together on a blue couch, holding hands while the couple on right, though sitting apart on separate chairs, is about to be hit by cupid’s arrow of love. It is possible that this couple is meant to represent Lucretia Chandler and her husband-to-be, Levi Willard, who supposedly was rather portly.

Cupid

Notice the baby-like Cupid above the second couple. He has just shot an arrow at the man and is still holding his bow at the ready. Cupid was a Greek god who helped couples fall in love by shooting them with his enchanted arrows. By including Cupid in this courting (or dating) scene, the stitcher demonstrates her knowledge of classical mythology.

Servants

Both couples are being served drinks and food on trays carried by servants who appear smaller than the couples themselves, perhaps to ensure that the elegantly dressed pairs remain the focus of attention in the image.

Gentleman Readers

Two men are shown busily engaged in reading brown books in the foreground on the left. Perhaps this reference to diligent study and book learning may be to demonstrate the importance of education to the Chandler family.

Furniture

In another effort to show off the family’s wealth, the maker has included several pieces of indoor furniture brought out of doors. A servant stands near a small wooden table at left, the readers in the foreground sit on tiny stools, the older couple sit together on the blue couch, and the courting couple sit apart on wood chairs.

The House

The maker has also included the family house in the background. A grand house for the time, it has two chimneys and seven large six-over-six sash windows. The house is fronted with a brick wall with elegant gate. Above the door the date 1758 is stitched in black thread, most likely the year the needlework was completed.

Natural Setting

The scene takes place in a bucolic setting on a rolling lawn with dramatically large flowers and exotic leafy trees. Various birds are shown either in flight or sweetly perched near the wooing couples lost in conversation. At the bottom right, a small spotted dog stands by attentively.

Flowers

Mostly along the bottom and left edge, the maker has stitched a great variety of flowers in bloom.

Silk Embroideries

As the late 18th century wore on, the neoclassical style became increasingly popular in America. This style took its cues from ancient Greece and Rome and emphasized elegant geometry and luxurious materials. This shift in style was reflected in the diminishing popularity of canvaswork and the sudden fashion for silk embroidered pictures.These shimmering pieces, worked at private schools in silk, an expensive material, were often hung in showy gold frames in the ‘best’ parlor of the house.

They served as decoration, and as a symbol of the maker’s sophistication. Silk embroideries dealt with a variety of themes and subjects including memorials, coats of arms, patriotic scenes and stories from classical antiquity, the Bible, history, and literature. Most of the subject matter for silk embroideries was copied from prints, many of which were found in contemporary books.

Jephtha

Jeptha’s Rash Vow, 1810

Silk, ink, watercolor, gold foil, gold fringe, velvet and fabric on silk, 21½ x 21½ in.

Lydia Royse School, Hartford, Connecticut

Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Stephen & Carol Huber

Biblical passages were very popular subjects for silk embroideries. One such story that was frequently worked in New England was that of Jeptha (or in some versions spelled Jepthah). Jeptha’s tale was particularly dramatic, which may account for some of its popularity. Jeptha, a judge in ancient Israel, was to lead the war against the Ammonites.

Before going into battle, he promised that if he should win the battle, he would sacrifice the first person who greeted him when he returned. The Israelites won the war, but unfortunately for Jeptha, the first person he met upon returning was his daughter, who came out dancing and playing the timbrel (a small hand drum like a tambourine). Needlework of Jeptha’s story typically depicted this key moment when Jeptha first returned home and realized how rash he had been and that, by his oath, he would have to sacrifice his own daughter. A bone-chilling story that was a favorite among the young needleworkers.

In these embroideries, it’s clear that Jeptha himself, still dressed for war in his helmet and uniform and accompanied by soldiers and flags, is distraught.

His face is downcast and he has thrown his arms up as if to block out the reality of his tragic situation. His daughter too and her friends, though holding musical instruments, show signs of emotional distress. They stand upon the front steps of Jeptha’s house, but the steps look more like a stage with elaborate curtains, reminding viewers of the drama of the scene.

It is also interesting to note that the scenes contain a mix of classical and more contemporary architectural elements. Though all three silk embroideries contain Greek columns and marble, (some contain classically dressed figures and urns too), one of the embroideries here features a white fence, a element favored by the Misses Pattens’ schools of Hartford.

Harriet Wells

Jeptha Laments His Rash Vow, 1812

Silk, chenille, metallic threads, and watercolor on silk, 20½ x 24½ in. Attributed to the Misses Pattens’ School, Hartford, Connecticut

Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Stephen & Carol Huber

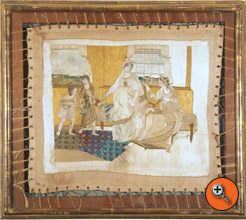

How to Make a Silk Embroidery

This unfinished piece offers a rare opportunity to see one of the mounting techniques used in creating silk embroideries.

The image was drawn on the silk, the silk stitched to a piece of canvas, the canvas hemmed, buttonholes created around the perimeter, and the silk then laced to the frame.

A 2nd century Roman matron, Cornelia was the widowed mother of three children and her purpose in life was to raise them to love and serve their country. Her reputation for goodness and wisdom was widespread and many rich and noble men proposed marriage, but she always declined so that she might watch over her children. A rich woman from Ionia came to visit and brought her “box of jewels” to show Cornelia and then asked to see hers. Cornelia, being of more modest means, pointed to her children and said, “These are my jewels.”

Undoubtedly this endeared the heroine to 19th century teenage girls and consequently Cornelia was often chosen to be depicted in needlework and watercolor. But also enticing to the student was the ending of the story.

For the two young boys grew to be famous Roman statesmen and accomplished many great deeds, they did, however, have a tragic ending and both were eventually murdered as a result of their good doings.

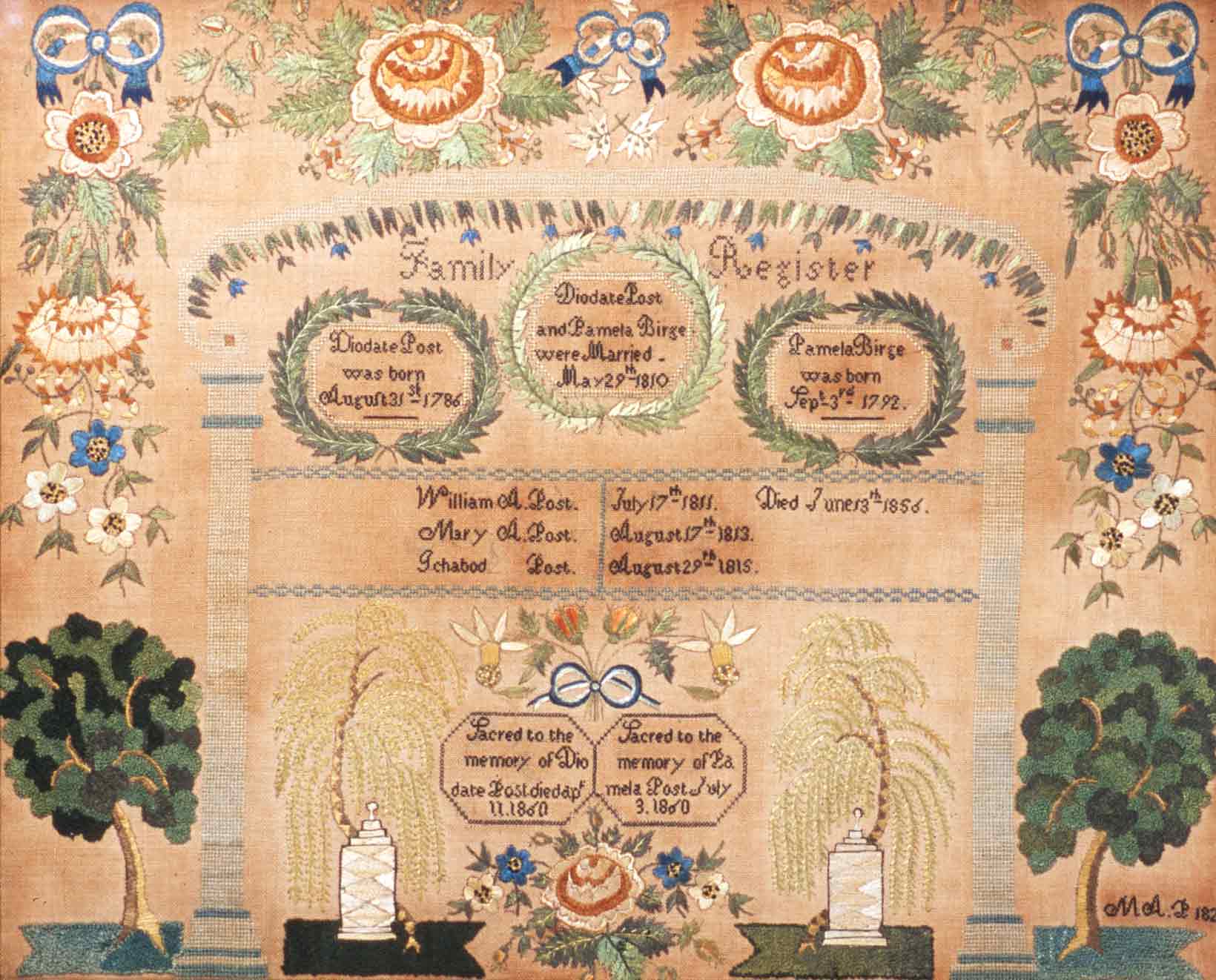

Memorials

Memorials were a type of silk embroidered picture that honored a beloved person who died.

Many schoolgirls choose to draw and paint memorials instead of sewing them, but they look very similar. In most cases, memorials were dedicated to a close friend or relative. Memorials were not usually completed at the time of a person’s death, but were often carefully planned out, and were meant to serve as a record of death, a decoration, and an expression of grief.The death of George Washington in 1799, however, fostered a nationwide wave of patriotic grief that included the creation of needlework memorials, many of which included images of the first President. The memorials below were made shortly after Washington’s death.

Things to Remember When Making a Memorial

The Mourners Dressed in Black

Most memorials feature images of mourners, the people who are sad at the loss of their dear friend or family member, dressed in black clothing. Black clothing was worn by family members at the time of the death and for sometime afterwards. A woman who loses her husband might wear black for up to four years. In some cultures, widows were expected to dress in black the rest of their lives out of respect for the dead.

Weeping Willow Trees

Memorials often contain image of weeping willow trees. The name and shape of these trees make an emotional connection to crying and sadness even though the trees are not really weeping nor are they sad. Nevertheless willow trees were often planted in real cemeteries because of their ability to absorb a great deal of moisture. The trees would suck up water and ensure that recently buried bodies would not decompose.

The Green Garden

Other symbols often included were a green landscape or garden which emphasized the Christian belief in heaven — a garden paradise. Evergreen trees symbolized eternal life because they remain green even in winter, and both oak and elm trees represented strength and dignity.

The Mourner’s Lean

To show both their sadness and connection to the person being remembered, memorials often show the mourners leaning on the monument with their elbow, holding their head in their hand. Sometimes the figures are show with handkerchiefs to catch their tears. Other figures shown around tombs are often positioned in traditional mourning poses with lowered heads looking sadly at the monument.

Classical Shapes and Motifs

Memorials will often contain monuments marking the graves of loved ones shaped like Greek urns or vases and reveal the maker’s knowledge and sophisticated appreciation for the past. These classical motifs reference the art of ancient Greece and Rome, cultures that the early Americans looked to as a models for a cultured society and government.

Other Clever Symbols

Memorials might include a cut flower or fallen tree as a symbol of a good life cut short.

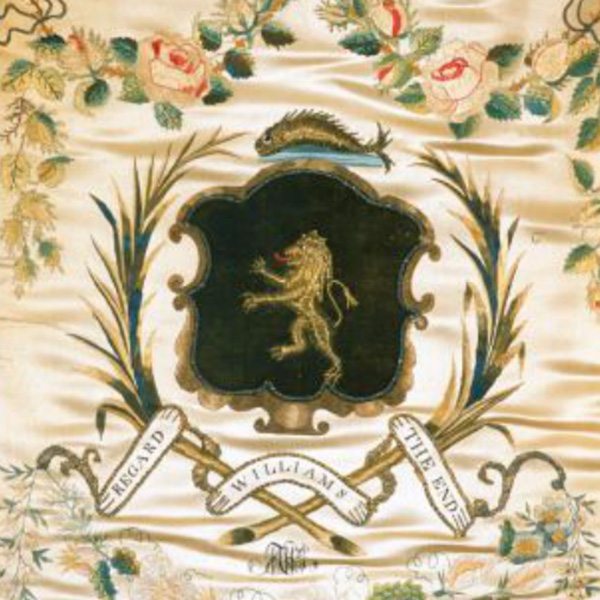

Coats of Arms

Another type of silk embroidered picture was the coats of arms, the grand symbol of the needleworker’s family. Such pieces demonstrated family pride and were often prominently displayed in the best room of the maker’s house.

Depicting a family’s symbol was an old tradition in Europe and was brought to New England with the Pilgrims, who used their own coats of arms as status symbols. Coats of arms were also painted on hatchments, diamond-shaped panels with a black background, which were hung on the house of the deceased in a ritual of mourning.

However, it was not until the 1740s, well over a hundred years after the first Europeans came to Massachusetts, that heraldry began to be used for decoration, though still usually in the traditional hatchment shape. At this point in time, coats of arms began to appear much more frequently and in many different forms: in paint, engraved on fine silver, and in needlework. Although it is unknown who first started instructing girls to embroider their family shields, the practice started in Boston, New England’s cultural center at the time. Highly decorated silk embroidered coats of arms became immensely popular and their creation persisted well into the 19th century.

Components of a Coat of Arms

A Central Shield

The central shield is the most important part of the coat of arms. Named for its shape, it essentially contains the distinctive design that is unique to the family. Certain patterns, animals, and symbols were commonly used including lions, castles, birds, crosses, and stripes. A shield divided might include elements from the father’s coat of arms on one half and the mother’s on the other.

In this Williams Coat of Arms, the shield is decorated with a rampant lion (a lion standing on his rear legs) and trimmed in gold.

Supporter

Design elements on either side of the shield.

In this Williams Coat of Arms, the supporters are graceful sheaves of wheat, entwined with the motto (see Ribbon or Banner below).

Ribbon (or Banner)

The ribbon or banner is usually located below the shield and features the family name or motto. The ribbon is usually held up in two places, leaving three areas for text.

In this Williams Coat of Arms, the three sections of ribbon reads: REGARD/ WILLIAMS/ THE END.

Helm (or Helmet)

Often, right above the shield, there is a helmet or crown.

In this Williams Coat of Arms, in the helmet area is a large fish.

Other Decoration

In this Williams Coat of Arms, the large padded eagle worked in metallic thread holding a floral garland was the signature characteristic of the beautiful coats of arms worked in the early 19th century at the Misses Pattens’ School in Hartford, Connecticut.

Although the Misses Pattens’ School in Hartford, Connecticut, was well-known for the embroidered coats of arms the students stitched, a few girls chose to paint their family arms. This example is done in watercolor. Characteristics of work done at the Patten School include the eagle at top holding a garland of leaves and flowers, and a central motif bracketed with flowering vines. The subject matter varies and in this case it is the Rogers and Ingraham coat of arms.

Inscribed on the bottom center ribbon: Virtue the Safest Shield/ Rogers and Ingraham

Glossary of Terms

Boarding School

A private school at which students live as well as study.

Canvaswork

A type of needlework in which yarn or thread is stitched onto a canvas base.

Chenille

A velvety cord made from short threads of silk and wool.

Chintz

A type of cotton cloth printed with colorful flowers.

Cross-Stitch

A particular stitch in needlework that forms an X.

Day School

A school at which students study, but still live at home.

Eglomisé

Gilded glass: gilded with gold leaf on the back of a glass panel.

Embroidery

Decorative needlework stitched onto fabric.

French Embroidery

Decorative needlework (embroidery) using a white yarn or thread on a white fabric creating a white on white design.

Linen

A type of cloth made from the fiber of the flax plant.

Linsey-Woolsey

Originally, a blend of wool and linen and later a blend of cheap wool and cotton.

Marking Sampler

A type of needlework that could be used as a model for patterns, letters, and numbers. Samplers became a way for needleworkers to show off their skill.

Memorial

A type of needlework that that often honored a dead loved one, famous figure, or important value. Memorials typically include mourning figures, a tomb, and weeping willow trees.

Needle

A pointed tool with a hole (eye) at one end used to draw thread through cloth. The first needles, made of bone, were used some 20,000 years ago, but in the time of schoolgirl needlework, needles were handmade out of metal.

Needlework

Sewn or embroidered work done with a needle and thread on fabric.

Needlepoint

A type of canvaswork that featured decorative embroidery.

Sampler

A type of needlework that featured letters, numbers, verses, pictures, and often the maker’s name and date. Samplers became a way for their makers to show off their skill.

Silk

A fiber (often made into cloth) produced by mulberry silkworms. Because of its strength and soft texture, silk was highly prized as a valuable material.

Silk Embroidery

Decorative needlework stitched onto silk.

Stitch

Most simply, a stitch is created when a threaded needle moves in and out through a cloth. However, stitches can also refer to a series of stitches formed in a specific way, for example, tent stitch. Finally, stitch also works as a verb, meaning the act of making stitches.

Warp and Weft

These terms refer to the two groups of thread that are woven together to make cloth. The warp goes up and down, it was the thread attached to the loom. The weft thread goes back and forth, it was the thread woven in and out of the warp.

Watercolor

A type of paint that mixes the color pigments with water rather than oil.

Weave

To form cloth by lacing strands of thread (or yarn) together, often in a warp and weft pattern. This was a way of making cloth out of the individual strands of materials like cotton, wool, and silk.