Learn

New England Identity

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm.

Thomas Andrew Denenberg is the Chief Curator and William E. and Helen E. Thon Curator of American Art at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine

Old Lyme and the Colonial Revival

The Colonial Revival remains one of the most persistent and persuasive influences in 20th-century American life. A cultural movement as much as an aesthetic style, this reinterpretation of colonial forms provided (and continues to offer) designs and behaviors that shaped architecture, painting—even rituals like holidays and the family vacation—for countless Americans. Nowhere is the phenomenon more important than in the art colony of Old Lyme, Connecticut—an archetype of the New England village that became a national icon in the decade that bracketed the turn of the century. As urbanization, industrialization, and immigration changed the way Americans lived over the course of the 19th century, many sought comfort in the quiet and seemingly timeless landscape of an idealized “old” America. Writers and artists explored the historic haunts of their ancestors and provided imagery that made a virtue of the past for the modern era. Specific communities such as Plymouth, Deerfield, and Salem, Massachusetts were accorded mythic status in the American imagination. Other towns, such as Litchfield, Connecticut, literally remade themselves as colonial towns—backdating Main Street by removing 19th-century structures and altering others to resemble Georgian architecture.

On the Connecticut shore—an easy trip from the metropolitan center of New York—Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse in Old Lyme became a gathering spot for artists seeking to escape the hustle and bustle of modern life for the peace and quiet of an imagined historic past. With a critical mass of talent, including the painters Henry Ward Ranger (1858-1916), Childe Hassam (1859-1935), and Willard Metcalf (1858-1925), who were translating the landscape at Old Lyme onto canvas, the town became a village for the nation.

By the 1930s, Hassam’s vision of the Congregational Church in Old Lyme could be almost any Main Street in people’s minds. As the United States developed into an urban nation, a population shift moved the emerging middle class from small town to city. Individuals worked for ever-larger organizations, and as daily life became a series of interactions with corporations and institutions rather than individuals, nostalgia for the personal economy of the New England village became rampant. So, too, did reverence for New England ancestry.

The romance of pre-industrial small-town life initially took hold in literary circles on the eve of the Civil War. Poets such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) and John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) as well as novelists like Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) made local historical myths seem real and disseminated the ideal of hearth and home to the growing nation.

Everett L. Warner (1877-1963) The Village Church, c. 1910 Oil on canvas Gift of Hannah Coffin Smith in Honor of Her Father, Winthrop Coffin

In an age that witnessed the construction of planned mill towns, such as Lowell, Massachusetts, and Willimantic, Connecticut, the historical imagery of Whittier and Longfellow provided a form of rhetorical cover for the new patterns of labor.

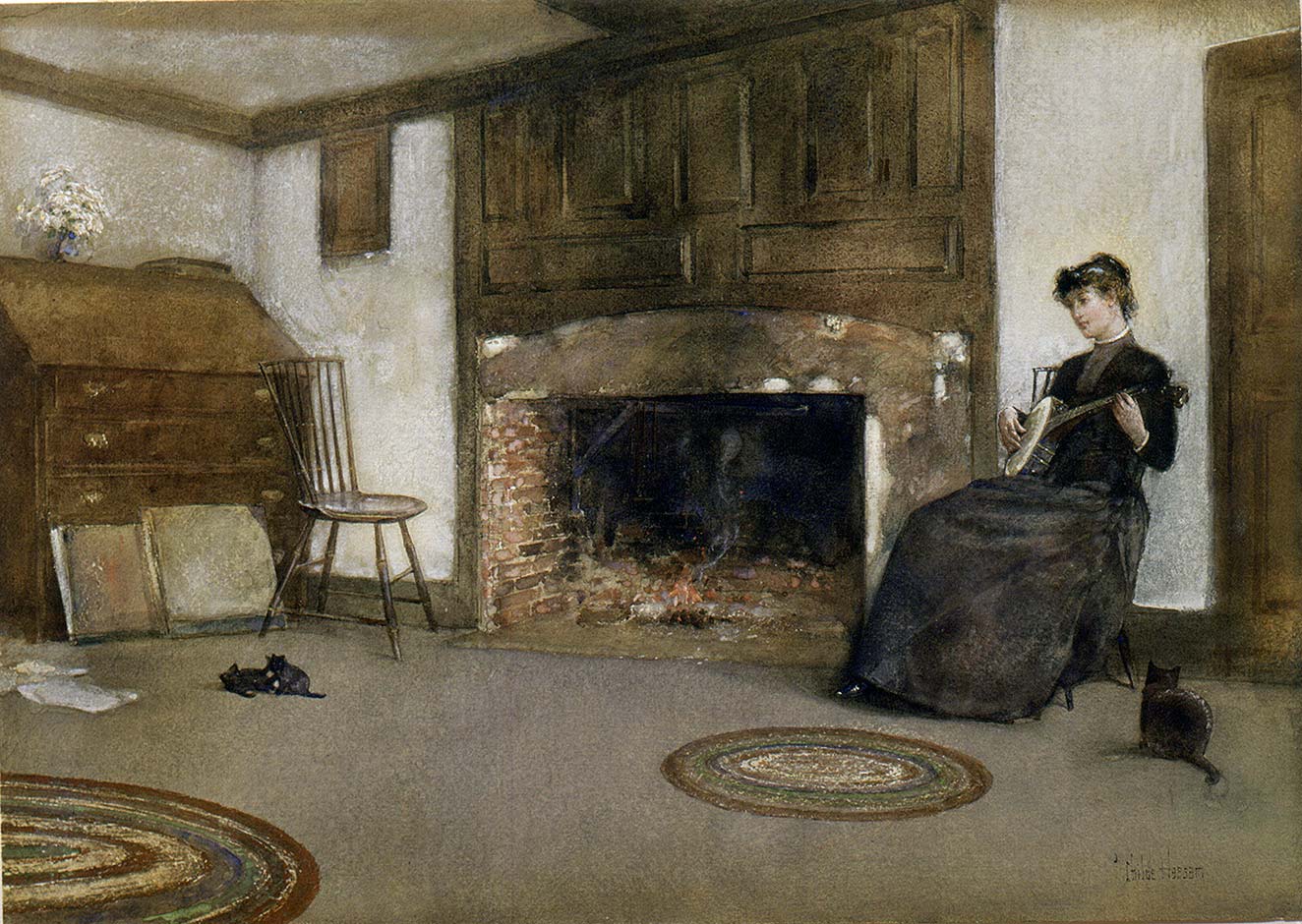

Textile production, by then located in the mills, was represented by the poets as a timeless activity for colonial women. Spinning wheels–obsolete domestic equipment of an earlier generation–were brought down from the attic and placed in the Victorian parlor to serve as mementos of female ancestral virtue.

Americans celebrated the past in public rituals during and after the great sectional conflict. “Olde Tyme” colonial or New England kitchens were focal points at fundraising fairs organized by the United States Sanitary Commission (a precursor to the Red Cross) during the Civil War. Historical re-creations of domestic hearth scenes, these public displays of filial piety often included women in period dress engaged in activities associated with their grandmother’s generation: spinning, weaving, and open-hearth cooking.

So popular were these theatrical vignettes that they were staged again at the great national celebrations that marked the Centennial of 1876 and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Separate installations displayed colonial relics, including 17th-century cradles, Revolutionary uniforms, and bandy-legged old chests. As the United States stepped onto the international stage as an industrial power at these great world’s fairs, it celebrated myths that fueled a full-scale colonial revival.

New England, home to relics and myths, became the nation’s attic in the waning two decades of the 19th century.

Collecting antiques, an eccentric pastime in the decades before the Civil War, became a normal hobby in the years after the Centennial of 1876. Colonial relics, such as a chair owned by the 17th-century governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony or the sword of Miles Standish, were once gathered for their historical associations.

By the 1880s, burgeoning demand for American furniture fueled a new market for “antiques.” Sophisticated critics, such as Clarence Cook (1828-1900), recommended antique silver, china, chairs, and chests for the home of good taste. The urban middle class, settling into a routine of vacationing at the mountains and the coast in New England, learned to patronize pickers and dealers while on holiday and returned to the city with an iconic Windsor chair, blue China plate, or silver tea pot for display in the parlor.

Artists mediated the distance between modern life in the city and historical culture in New England. Indeed, painters and photographers played a key role in the transformation of the colonial revival from a 19th-century literary culture to a visual language in the early 20th century. Painters such as Hassam and Metcalf chronicled hoary old houses and New England town centers for their wealthy patrons. Hassam, a denizen of summer colonies up and down the coast, employed a brushy style to render recognizable architectural monuments in a universal manner. His brooding depiction of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts—understood to be the oldest wooden house in America—captured popular belief about the stoic lives of the 17th-century Puritans.

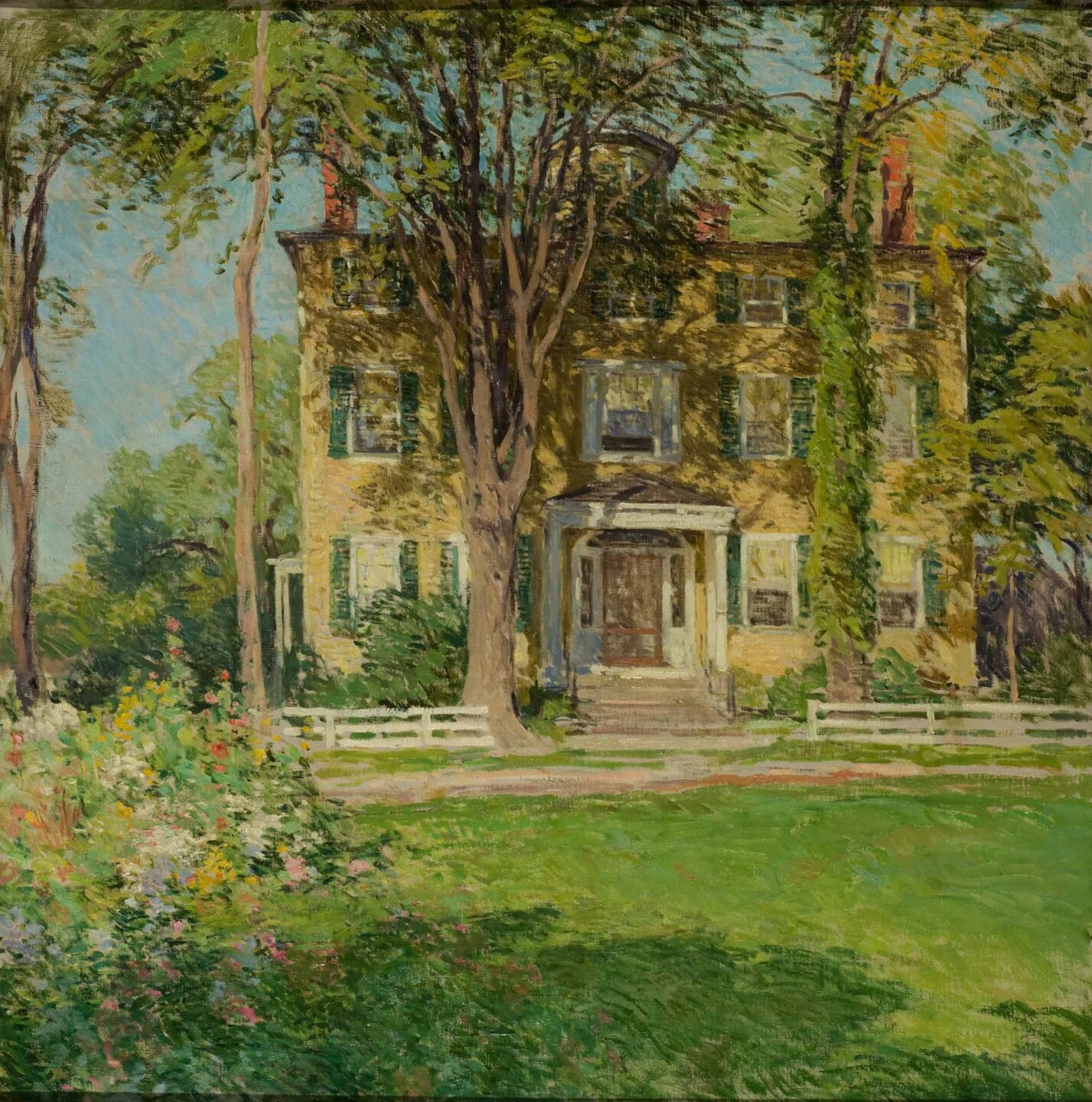

His paintings of meetinghouses—most famous of which are the multiple versions of the Church at Old Lyme—served as a catalog of these iconic structures. Metcalf’s Captain Lord House, Kennebunkport, Maine is a quintessential visual statement of the colonial revival on canvas. Bathed in light, the stately Federal mansion-house represents the golden age of trade in the young nation. Identified by title as a shipmaster’s house, the three-story structure provided a narrative about the virtues of commerce for an era of expansion.

The delivery system for such imagery into popular culture often came in the form of imitative photography. Wallace Nutting (1861-1941), a Harvard-trained Congregational minister, took up photography in the last years of the 19th century and turned this hobby into a business by providing an inexpensive alternative to easel paintings for the growing middle class. His A Colonial Three Decker, for example, bears a striking resemblance to Metcalf’s Captain Lord House but cost a small fraction of the price of the original.

Willard Metcalf (1858-1925) Captain Lord House, Kennebunkport, Maine, c. 1920 Oil on canvas Gift of Mrs. Henriette Metcalf

A prolific author as well as a talented shutterbug, Nutting published some 26 books and a large handful of articles on American furniture and the beauties of colonial America before his death in 1941. Nutting also branched out to own a chain of house museums and a reproduction furniture company that provided high-end colonial revival furniture for those who could no longer afford the real thing or preferred “new” antiques. By the time of Wallace Nutting, consumer culture had caught up with the colonial revival. Large furniture companies in Boston, Massachusetts, High Point, North Carolina, and Grand Rapids, Michigan offered “colonial” lines at all price points. The rise of suburbia added fuel to the fire. The historicizing impulse of the small house movement in the 1920s and 1930s ensured that the American dream would be located in countless capes, saltboxes, garrisons, and other colonial house types from coast to coast. Indeed, for every modern house built in America, an exponential number of colonial revival homes dot the landscape to this day.

The colonial revival holds sway in the United States to this day. Trading upon the mythic image of “old” New England, this national recycling of historic architecture, decorative arts, and even landscapes guaranteed a place for the past in modern life. A humorous high point to the story of the colonial revival and small town Connecticut came in 1948 when Cary Grant and Myrna Loy starred in the film Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House. The quintessential harried New Yorker, Jim Blandings (played by Grant) flees to Connecticut, “the land of steady habits,” to restore an old house. Blandings, like so many who came before him and followed thereafter, traveled a well-worn path created by artists, writers, and architects who looked to towns such as Old Lyme to provide models for the nation in the 20th century.