Fox Chase

Griswold House

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

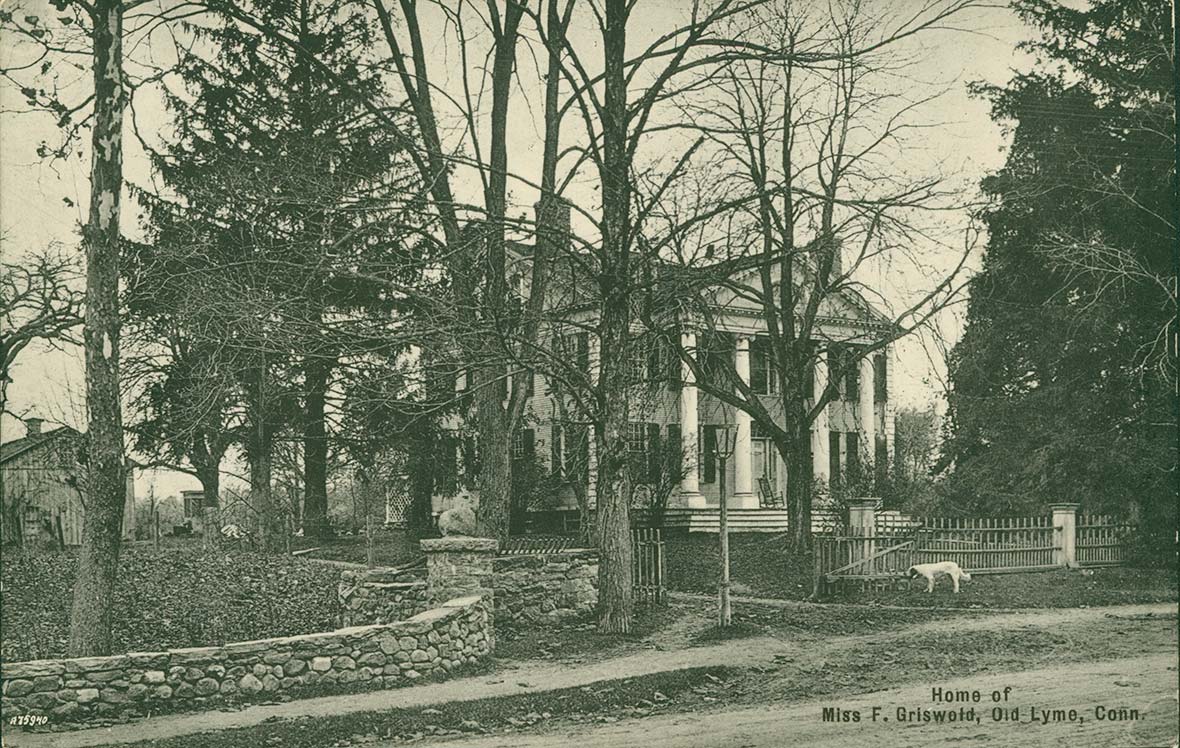

The Griswold boardinghouse is located on Lyme Street in the village of Old Lyme, Connecticut. It was built for the Noyes family in 1817, and later purchased by the prosperous sea captain Robert Harper Griswold in 1841.

By the late 1890s, the captain’s youngest child, Florence, was fifty years old and virtually alone in the world.

She inherited the house, along with its debts. To survive, she chose to take in boarders, turning the private home into the Griswold boardinghouse. This was a common and socially acceptable occupation for women at the time.

Unlike most boardinghouses, however, hers was filled with painters. One of her first boarders was the artist Henry Ward Ranger, who decided the house was the perfect place to set up an artist colony.

Image Yourself as an Artist

Imagine yourself as an artist arriving at the Griswold boardinghouse.

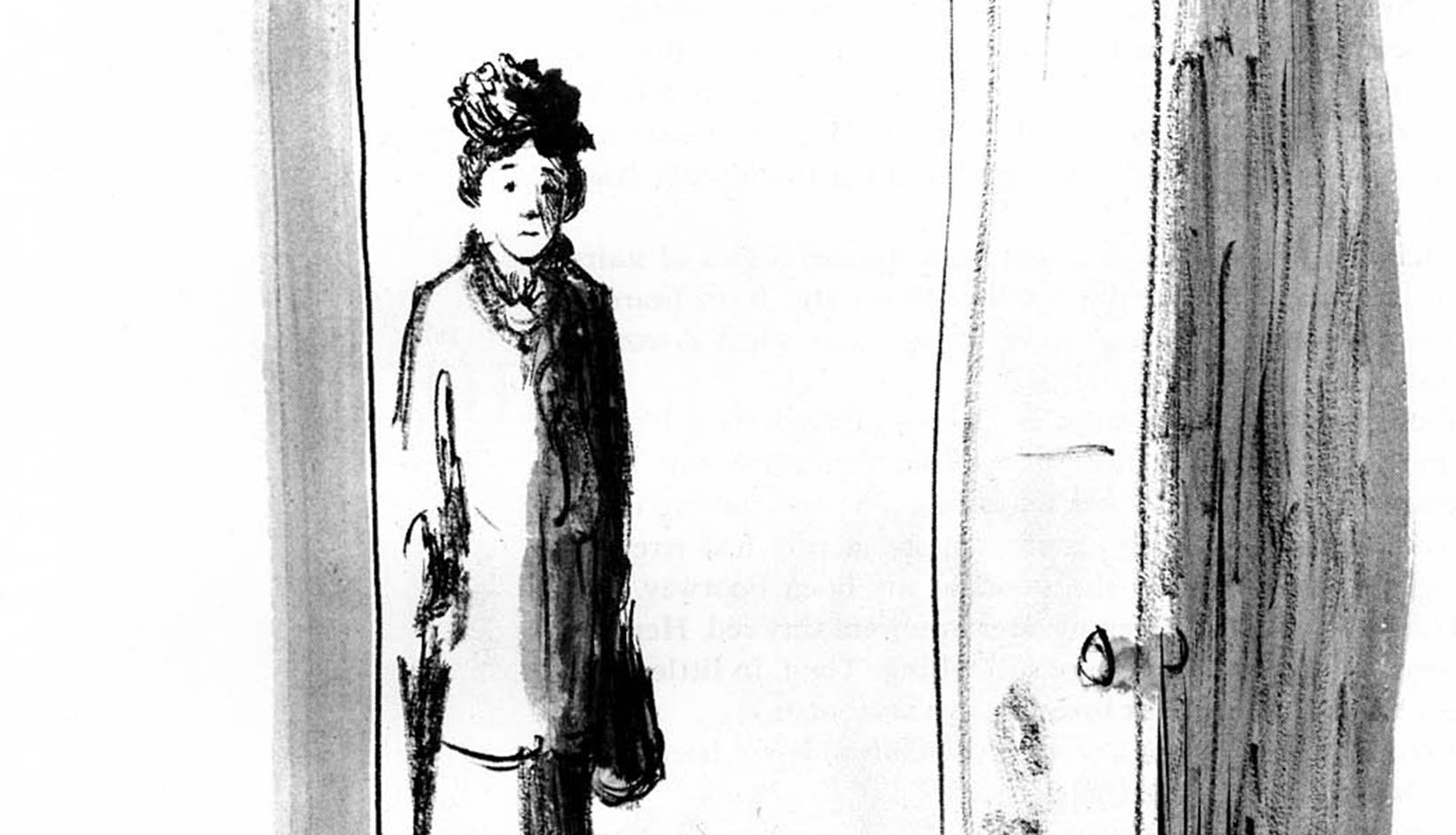

If you were one of the hundreds of artists to make the journey from New York to Old Lyme to stay in the Griswold boardinghouse, your arrival might just fit the model below.

After your journey by train from the grit of New York City,

you cross the Connecticut River via the ferry Colonial to the green countryside of Old Lyme. You arrive at the house by foot or by carriage with your traveling trunks and painting supplies. You enter the cool and shadowed hall of the house and are shown to your room to unpack your belongings.

James H. Stevenson Illustration (artist arriving at the boardinghouse)

Pen and ink on paper

Inside the Boardinghouse

Tour the Inside of the Boardinghouse for Artists

Welcome to the boardinghouse for artists.

By 1910, the wear of ten painting seasons was showing on the stately old Griswold House.

Now a favored and revered artist destination, the “Holy House,” as art students dubbed it, was in need of modernization and maintenance. In anticipation of a busy summer season, Miss Florence took out a second mortgage on her house to finance a list of luxuries, including indoor bathrooms, hot running water, furnace heat, electricity, and telephone service.

This same year, working in secret, a group of artists took it upon themselves to freshen up the common areas of the boardinghouse while Miss Florence was away. New paint and fashionable wallpapers were applied to the crumbling walls. Choice old furnishings were refurbished and reupholstered, and new carpets were ordered. This was the artists’ gift to Miss Florence. Despite the updates, the boardinghouse retained its timeworn charms.

The newly refurbished Griswold House opened to the public on July 1, 2006 as the Boardinghouse for the Lyme Art Colony, c. 1910.

Art Colony Bedroom

After being used for decades as the Griswold family’s formal parlor, this large front room was converted into a bedroom to be rented to distinguished guests staying at the boardinghouse. Architecturally one of the nicest rooms in the house, it features a beautifully carved mantel and ornate scrollwork over the door. Papered in an elaborate Victorian pattern reminiscent of its earlier role as a parlor, this room is generously appointed with Griswold family heirlooms, paintings, and artist materials.

An artist staying here would inevitably begin by unpacking his trunks and settling into his room.

Soon the room was cluttered with personal effects, along with magazines, art supplies, drying canvases, sketchbooks, brushes, and paint boxes. There was one other guest room on the first floor (currently an orientation gallery), five on the second floor, and a maze of makeshift rooms on the third floor. Room service was limited to the daily delivery of a fresh pitcher of water for washing.

Miss Florence's Bedroom

Originally used as a sitting room or office for Miss Florence’s father, Captain Robert Griswold (1806-1882), this room became the private apartment for Miss Florence during the art colony years. Conveniently located between the public areas of the boardinghouse and the more private areas where staff worked on meals and routine chores, this room provided Miss Florence with easy access to the different areas of the house. It was also her only truly private space.

In it she surrounded herself with cherished family possessions:

the telescope used by her father the sea captain, china plates decorated by her sister Louisa when the house was a home school for girls, and a winter landscape painting by her sister Adele.

Miss Florence’s Bedroom showing fireplace, 2006 Photograph by Joseph Standart

As the self-identified “keeper” of the art colony,

Miss Florence played well the shifting roles of mother, art dealer, confidant, and friend to her ever-changing roster of artists. She became a dear friend to Childe Hassam, perhaps the most celebrated of the artists to stay in Old Lyme, and she charmed the future President Woodrow Wilson, who came with his first wife, an aspiring painter.

Although she never married nor had any children, the painters filled her house and the last decades of her life with joy. Miss Florence revealed her pride in the impact her boardinghouse had upon the town when she said, “So you see, at first the artists adopted Lyme, then Lyme adopted the artists, and now, today, Lyme and art are synonymous.”

The Center Hall

More than a passageway, the center hall was used as a sitting room, an informal playroom (even for ping pong!), and a sales gallery for art and antiques. Cooled by the cross breezes that passed through the shuttered doors, boarders read and relaxed on the mismatched furniture that lined the hall. Here, amidst her boarders at leisure, Miss Florence greeted the many visitors who stopped for a tour of the painted door panels with hopes of catching a glimpse of the artists at work. In anticipation of the visits, she filled the hall with historic furniture and collectibles and hung art colony paintings available for sale.

The hall was one of the dilapidated spaces refurbished by the artists in 1910.

Remembering his first impression of the hall, artist Arthur Heming recounted that “several cats and dogs slept soundly and breathed heavily among the chaos of faded and tattered cushions and ripped and gaping upholstery” and described “mildewy and tattered wallpapers of forty years old design.”

Center Hall looking towards front door, 2006 Photograph by Joseph Standart

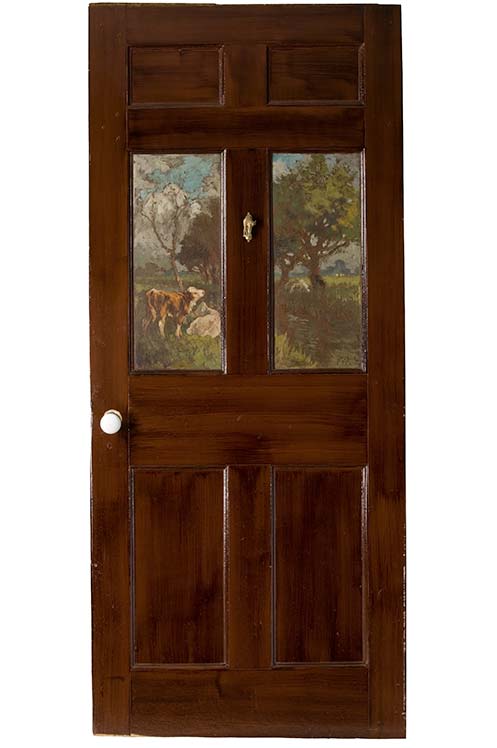

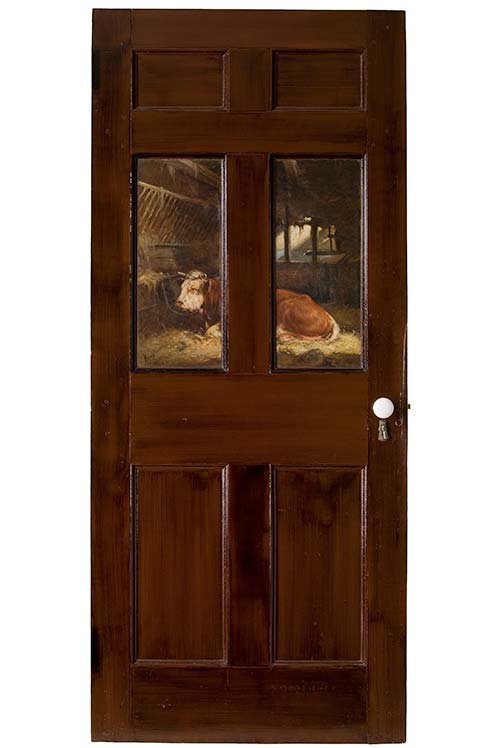

During the first summer of the art colony, Henry Ward Ranger painted a moonlit image of the Bow Bridge on the right inset panel of the door to his bedroom.

Then he challenged a fellow artist to paint a complementary scene on the other panel. This began a tradition of painting on the doors of the first floor that continued throughout the public areas of the house and culminated in a remarkable collection of painted doors and wall panels in the dining room.

Art Colony Parlor

Although used throughout the day, the parlor was especially active during the evenings. The artists moved into the parlor after dinner to continue their boisterous conversations. Here they entertained themselves with spelling bees, card games (primarily poker and bridge), and impromptu theatrics. On occasion, they tested each other’s artistic skills by playing the wiggle game, an artful competition to see who could best incorporate three “wiggles” on a piece of paper into a complete and often humorous drawing.

The artists moved into the parlor after dinner to continue their boisterous conversations.

Here they entertained themselves with spelling bees, card games (primarily poker and bridge), and impromptu theatrics. On occasion, they tested each other’s artistic skills by playing the wiggle game, an artful competition to see who could best incorporate three “wiggles” on a piece of paper into a complete and often humorous drawing.

Piano niche in Art Colony Parlor, 2006 Photograph by Joseph Standart

The Pantry

Originally a very deep pantry, this space was altered in 1910 to make room for the installation of the first floor bathroom. This smaller pantry was where the many sets of dishes, glassware, linen, and other tableware were stored between boardinghouse meals. The shelves were stacked with linens and tableware. The pantry is connected to the back hall, the service area of the home.

Art Colony Dining Room

The tradition of painting on the doors of the boardinghouse reached a crescendo in the dining room. The artist Willard Metcalf suggested decorating the dining room with painted panels held in place by varnished strapping. The 44 panels by 33 artists cover the four walls. The panels are sandwiched between the wainscot below and a china rail above, displaying Miss Florence’s collection of antique ceramics. The subject matter of the panels mirrors the interests of the painters of the colony and includes Lyme landscapes, bucolic rural scenes, woodland interiors, and a few exotic images of the Far East, Venice, Spain, and New York.

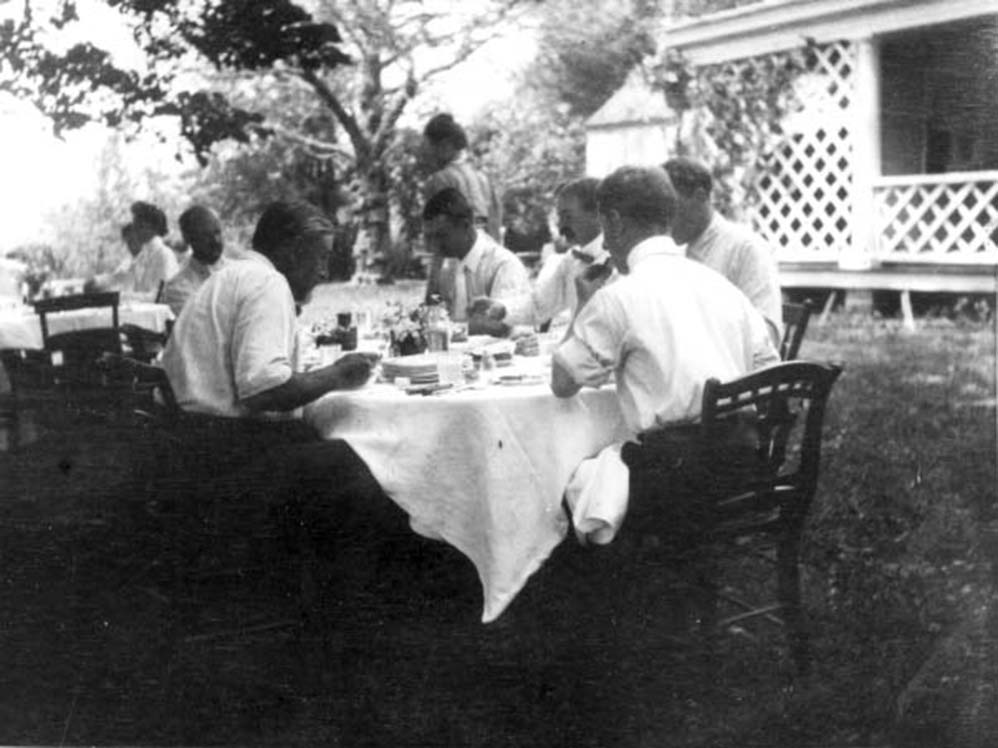

A favored room of the artists,

the dining room has a low ceiling, wide-plank floorboards, and large brick fireplace that suggested a connection to colonial America. Women and men often sat at separate tables. Miss Florence would move from one table to the other enjoying, and perhaps instigating, the animated conversations at both. Often the artist William Henry Howe, who was famous for his paintings of cows, would be asked to carve at table because of his great knowledge of animal anatomy. Overall, meals were simple (roast beef, turkey, ham) but substantial and often included fresh vegetables from Miss Florence’s garden and fruit from the orchard baked into pies.

Art Colony Dining Room, 2006 Photograph by Joseph Standart

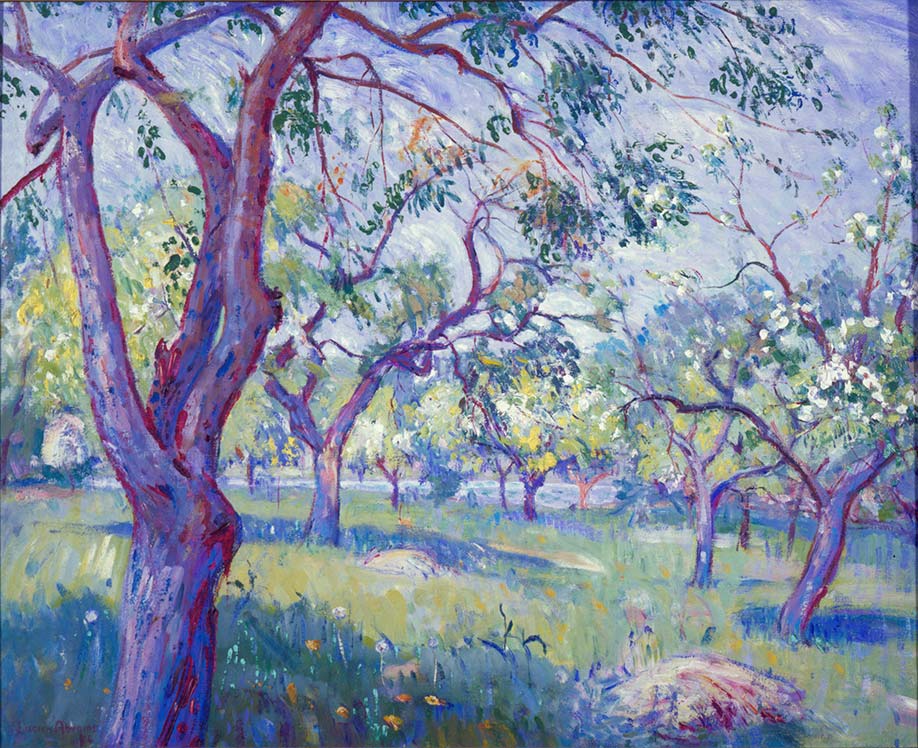

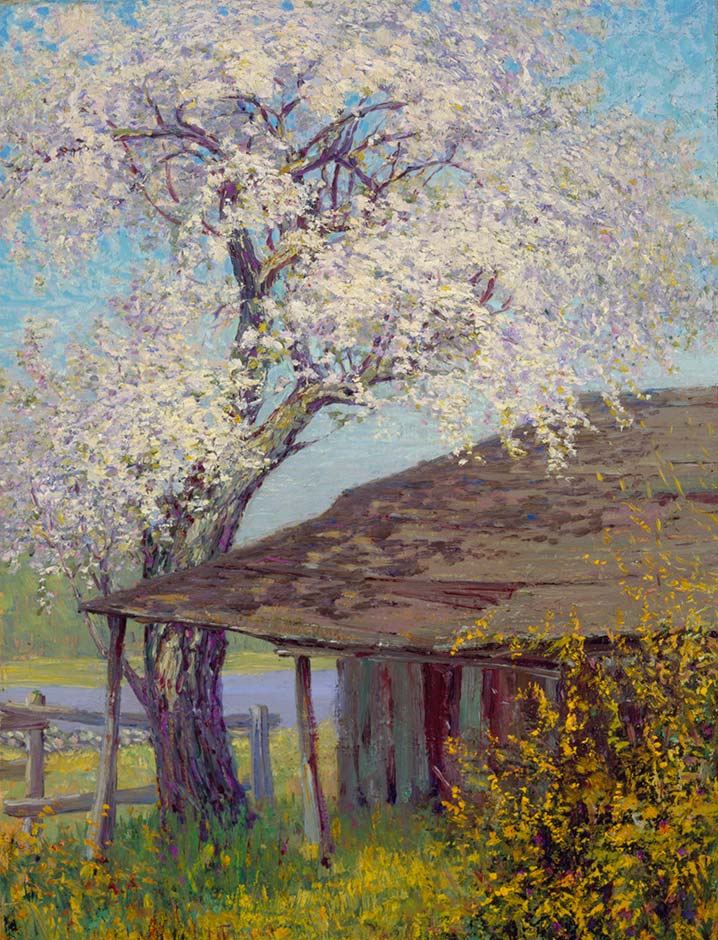

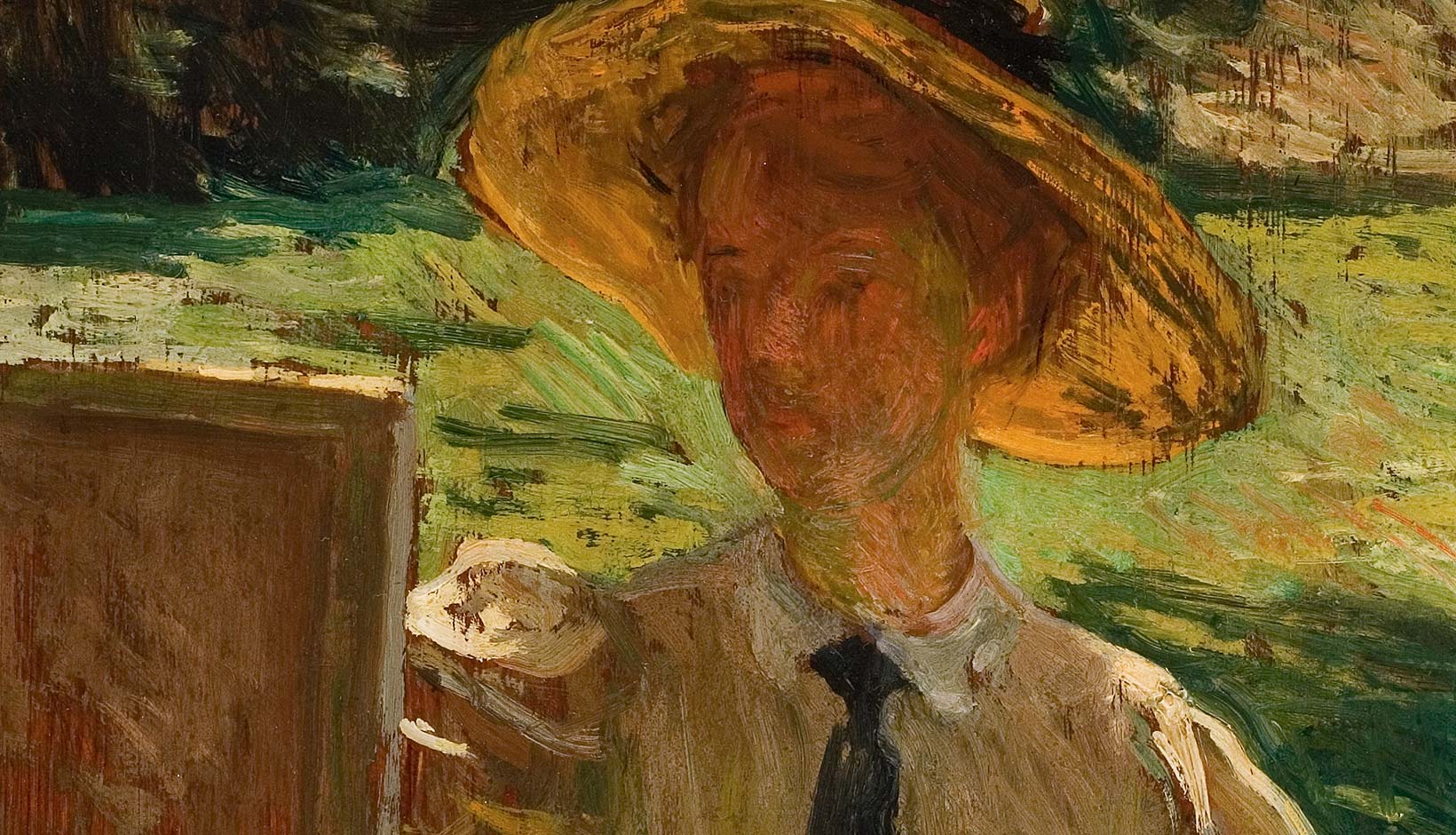

Over the fireplace is The Fox Chase,

a painted parody of the hunting scenes depicted in the English prints above, peopled with artists associated with the Lyme Art Colony during its first five years (the colony continued in some form until Miss Florence’s death in 1937).

Shown running through the village from the Griswold House to the marshes beyond the First Congregational Church, the members of the colony are playfully identified through their foibles and idiosyncrasies. The rotund Henry Ward Ranger, dressed in tell-tale browns like those in his pictures holds his heart at one end of the frieze-like composition, while Childe Hassam, stripped naked from the waist up, paints en plein air, or outdoors in the manner of the Impressionists, at the other.

Between the two rivals are the artists who came to Lyme during those early years to forge a new chapter in American art history. The good-natured air and self-mocking fun of the painting reveals the camaraderie of the art colony, which was as Hassam liked to say, “just the place for high thinking and low living!”

Outside the Boardinghouse

Tour the Outside of the Boardinghouse for Artists

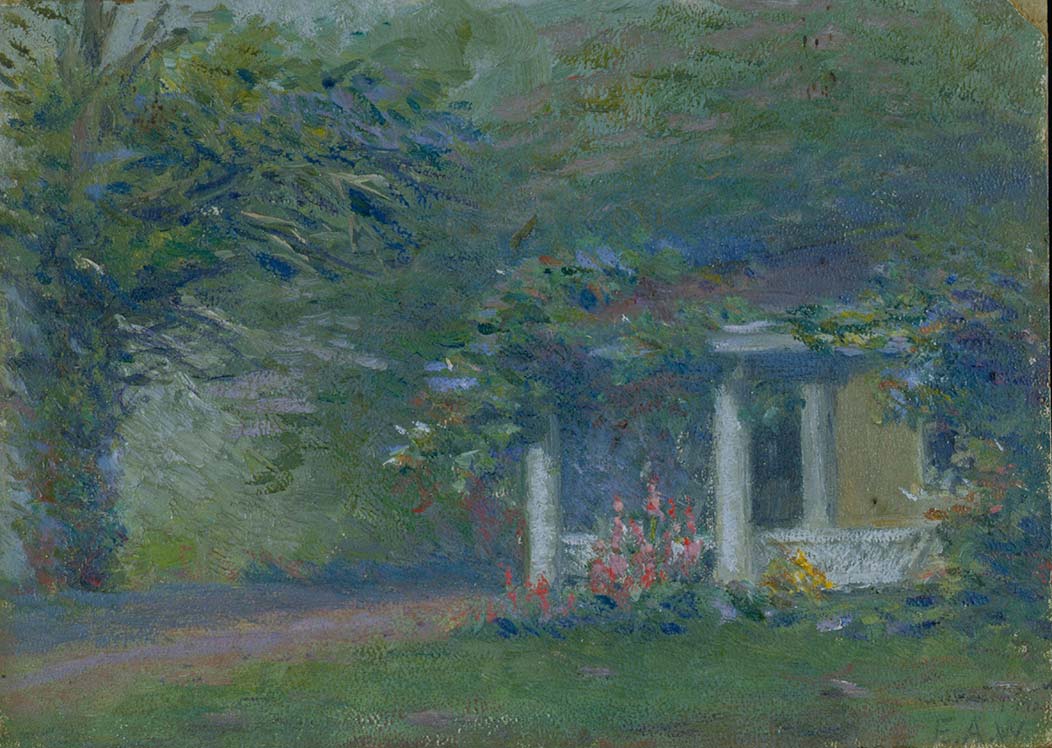

The Griswold House and the surrounding grounds and gardens were popular subjects for the artists. The original property consisted of 12 acres of land nestled between Lyme Street and the Lieutenant River, a tidal waterway that empties into the larger Connecticut River. In addition to the house, the grounds boasted several barns and small outbuildings, vegetable and flower gardens, an apple orchard, horse paddock, stream, and well house.

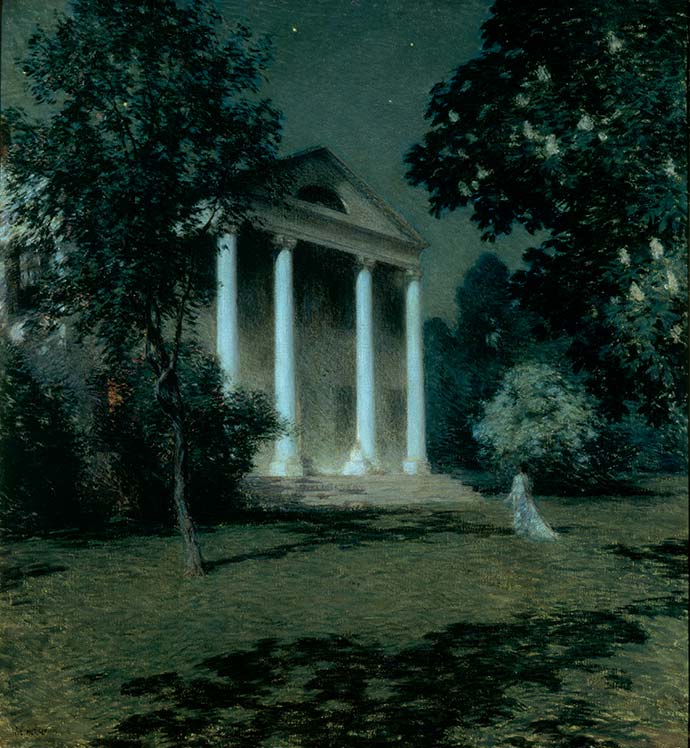

The Griswold House

The Griswold House, originally the William Noyes House, was designed and built by Samuel Belcher (1779-1849) of Hartford. It was one of the largest houses in Old Lyme and was situated towards the north end of the village. Late Georgian in style, the house featured four imposing columns with ionic capitals, a grand pediment, fan lights over the door as well as in the pediment, and wooden quoins in the corners of the main building. It was one of three buildings in Old Lyme built by Belcher. He also designed the John Sill House (now the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts) and the Lyme Meeting House (now the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme).

The house changed owners and uses several time over its nearly 200 year history.

Originally built for the Noyes Family, it was purchased by the Griswold Family in 1841. During the 1880s, the Griswolds converted some rooms into classrooms and ran a finishing school for girls. By the late 1890s, the family needed money and began renting rooms. By 1910, the wood siding was painted yellow, the trim white with yellow insets, and the shutters a rich green.

The Griswold boardinghouse was in operation in varying degrees of occupancy until Miss Florence’s death in 1937. It remained unoccupied during the Second World War in the early 1940s, but opened as a local history museum beginning in the summer of 1947. It housed the collection and exhibitions of the Florence Griswold Museum for the second half of the 20th century. In the summer of 2006, the first floor of the house was reinterpreted as the boardinghouse for the Lyme Art Colony, circa 1910. The rooms on the second floor are used for a long-term installation that documents the Lyme Art Colony in photographs, artifacts, and paintings.

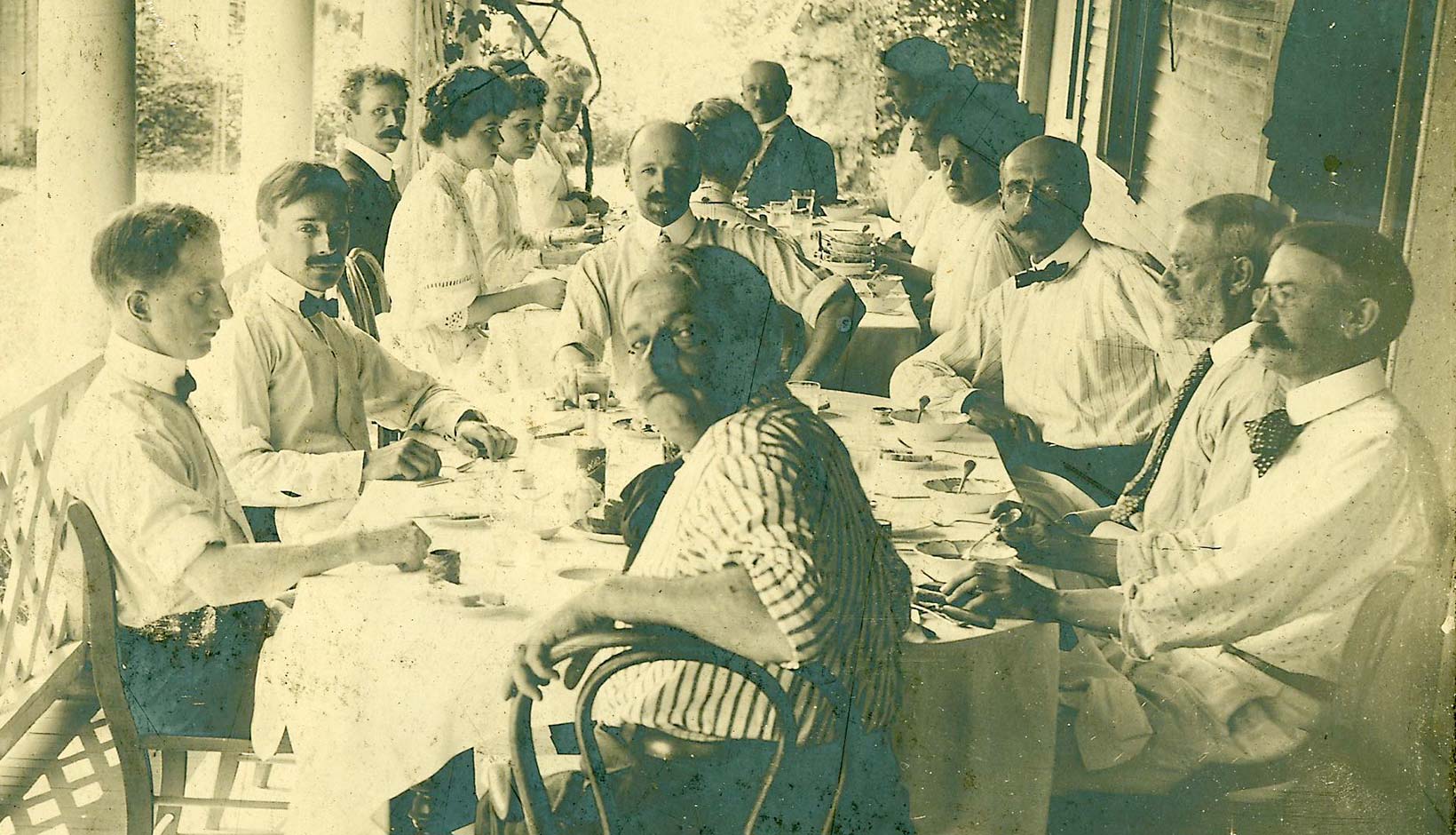

The Side Porch

The side porch became an extension of the living space of the house, especially for meals when the dining room became stifling with humid summer heat. It also provided views towards the barns and gardens. At the far end, a trellis covered with an ancient grape vine, provided dappled shade and a sense of privacy in this cloistered space.

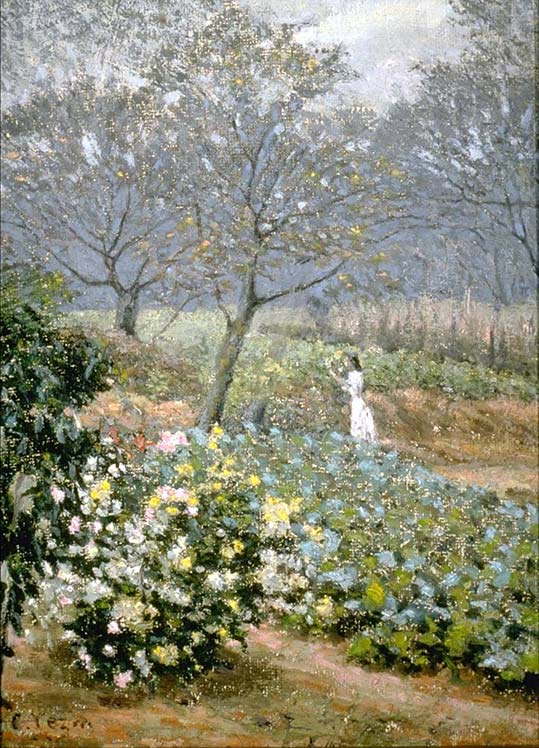

The Gardens

The gardens behind the house were always an important part of the landscape. Miss Florence was an avid gardener and would mail order heirloom bulbs and other specimens from flower catalogues. Behind the house there were three distinct gardens, two for perennial flowers and a smaller one for herbs and vegetables. There was also a row of lilac trees and flowering shrubs that bordered the walkway to the outhouse.

These gardens have been replanted using historic photographs and paintings, as well as the gardening preferences of the time. Known as “Old-Fashioned” or “Grandmother’s” gardens, these planting beds featured flowers with associations to the colonial past, such as hollyhocks, phlox, and delphinium. Unlike the more formal gardens of the Victorian era, these gardens were meant to look untamed, often overspilling their tidy beds.

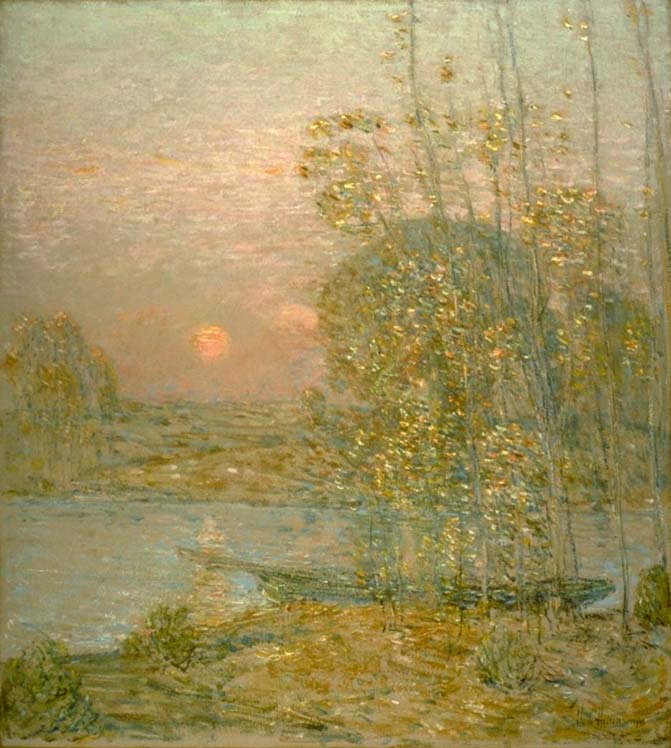

The Lieutenant River

The Griswold property is bordered to the west by the Lieutenant River, a 4-1/2 mile long waterway that meanders through the village of Old Lyme. The Lieutentant River joins the larger Connecticut River (the longest river in New England) just before it empties into Long Island Sound. A tidal river, the Lieutenant River is in constant flux. The tide brings water northward, filling the small river to capacity and flooding the grassy marshes along its banks. Six hours later, the tide retreats and the brackish mixture of salt and fresh water flows out towards the sea, leaving behind the rich muddy banks.

Artists in a canoe

The river was both a playground and painting subject for the artists. Using Miss Florence’s disheveled fleet of rowboats or a borrowed canoe, the artists would investigate the river and the maze of waterways in the marsh on the far side of the river. Once back on land, the ever-changing light upon the river and the myriad of greens in the marsh grass captured their artistic imaginations.

Chadwick Studio

Many of the studios that long stood on the Griswold property vanished under the ravages of time. One historic barn that was used by the artists still stands behind the house, but a second one had fallen down and was rebuilt somewhat larger in 2000 to accommodate the Museum’s Hartman Education Center. In 1999, the Museum commissioned an archaeological dig of the property, which unearthed thousands of artifacts, including the buried bits and pieces of the studio used by Childe Hassam (smartly situated between the gardens and the river), along with paint drippings and the remains of a tin painter’s box.

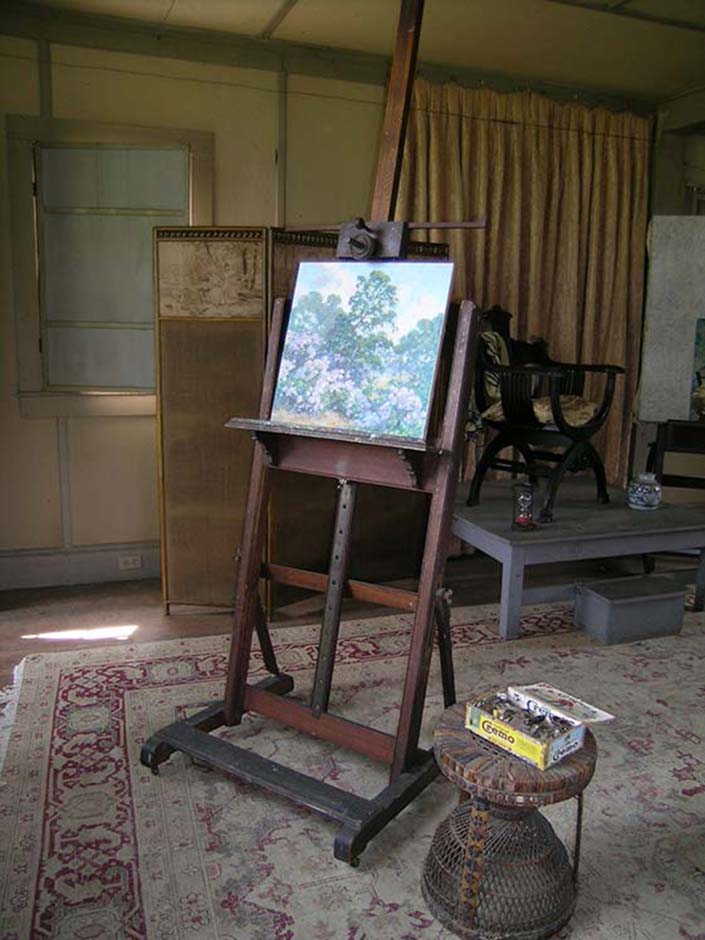

Near the southwest corner of the property

is the studio of American Impressionist William Chadwick (1879-1962), a member of the Lyme Art Colony. Although not original to the property (the studio was moved to its present location in 1992 from elsewhere in Old Lyme), it is a demonstration of how an artist might organize his creative space. The studio has three main areas: workshop, studio, and second floor. Originally an icehouse, the workshop area is filled with tools, canvases, frames, and shipping crates. The studio portion was made homey with an area rug, wood stove, and desk with lamp.

Chadwick was known to hang a sign on the studio door

that read “resting” while napping on the soft daybed. It is also a practical space for painting, with the large northern window, a wide workbench for mixing pigments and organizing painting tools, and a model stand set with studio props. Chadwick was a talented figure painter as well as a landscapist, who worked in a high-key Impressionist style. His easel stands in the middle of the room, displaying one of several facsimiles of his paintings.

Who's Who

Learn About the People in the Boardinghouse

The cast of characters that enlivened the Griswold boardinghouse was as distinctive as the art of the Lyme Art Colony. Miss Florence and her small domestic staff provided year-round assistance to the boarders, made up almost exclusively of artists and their family and friends. On occasion, they would host a dignitary such as Woodrow Wilson. Non-boarding visitors also came on a regular basis and included tourists, art students and locals coming to dine. Together they formed an artistic community that continues to influence American art today.

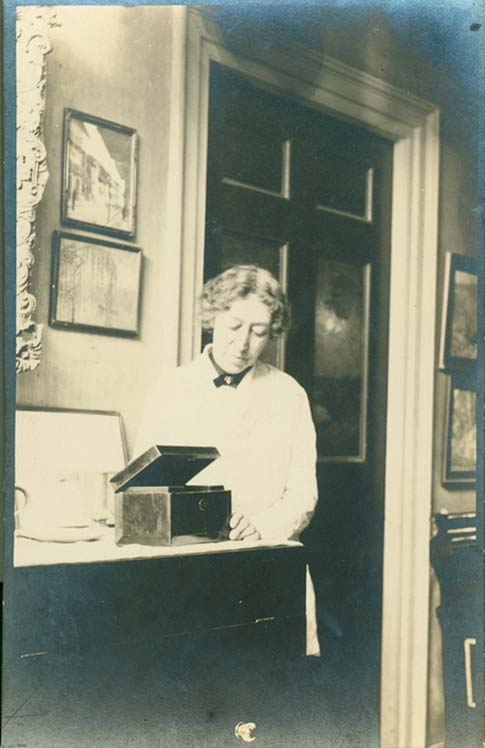

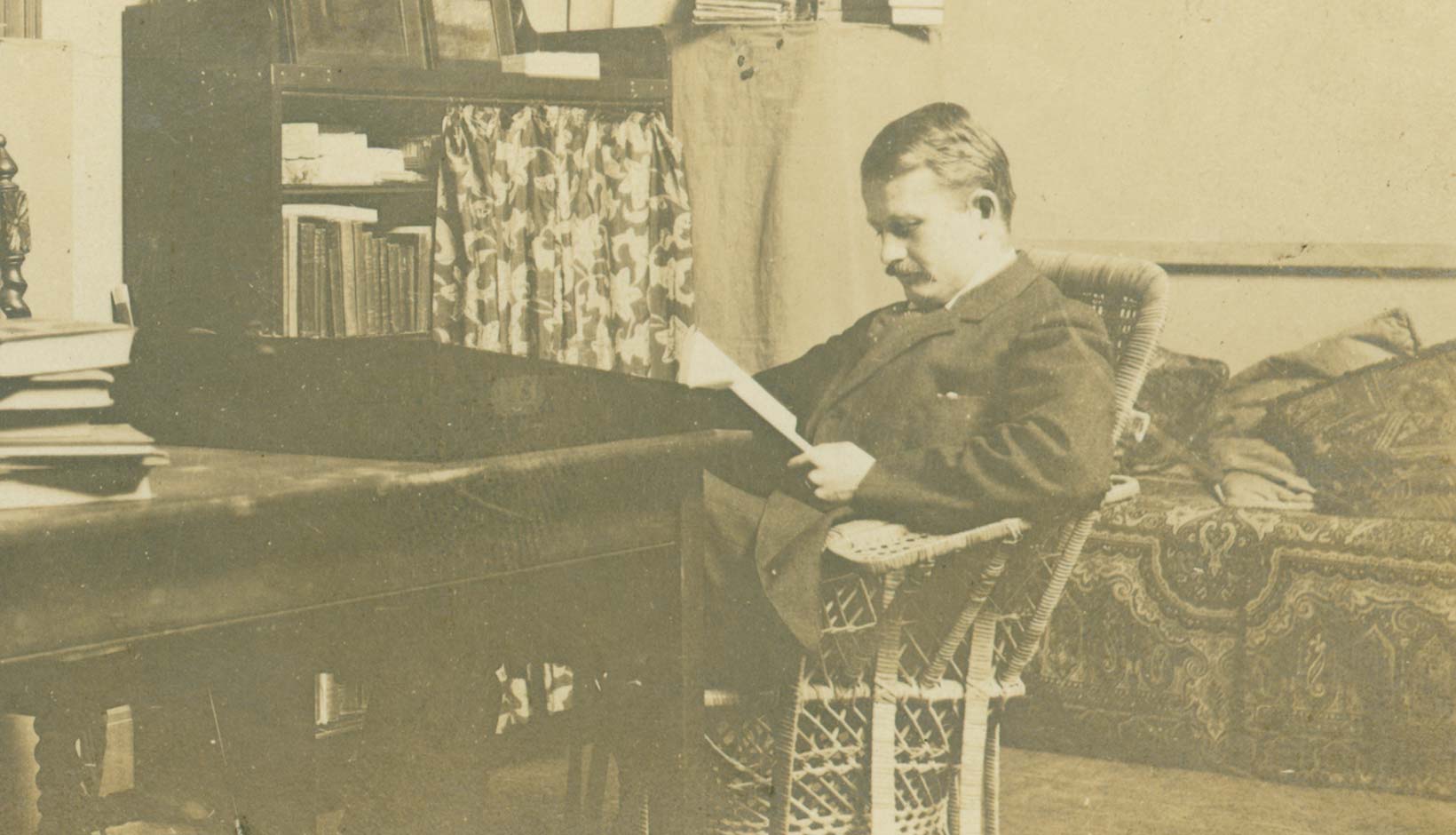

Miss Florence Griswold

Born on Christmas Day in 1850, Florence Griswold experienced a delightful childhood, surrounded by loving family and enjoying the charmed lifestyle of a well-to-do sea captain’s daughter. The family lived in one of the largest homes in town and the girls attended a private school run by an aunt in New London. Florence was adept at music, excelling at guitar, piano, and harp, and also rode horses. It wasn’t until the Captain retired that the financial stability of the family was threatened. His early retirement and bad investments prompted the sisters to open up the Griswold Home School to teach and board young ladies, a resourceful venture that was marginally successful for nearly 14 years. By the end of the century, the family had opened the house to boarders.

Florence took the lead in running the Griswold boardinghouse.

Not only was this a socially acceptable way for an unmarried woman to make a living, but Florence had some prior experience from her work with the girls’ school. Her success, however, came from her savvy abilities to accommodate her very specific clientele: the artists. By nurturing them (and at times their fragile egos) during their stay and inviting them back year after year through a persistent campaign of letter writing, Florence was able to sustain the longevity of her boardinghouse, and had guests staying with her up until her death in 1937.

James H. Stevenson, Detail of Illustration (Miss Florence arriving back home), 1971 Pen and ink on paper

Miss Florence, as keeper of the boardinghouse, was responsible for

sorting out the comings and goings of up to 16 guests at a time and allocating the rooms and studios. For room and board she charged the artists approximately $7 a week. In addition to their meals, boarders received a fresh pitcher of water daily and use of one of the kerosene lamps to light the way to their rooms after dark.

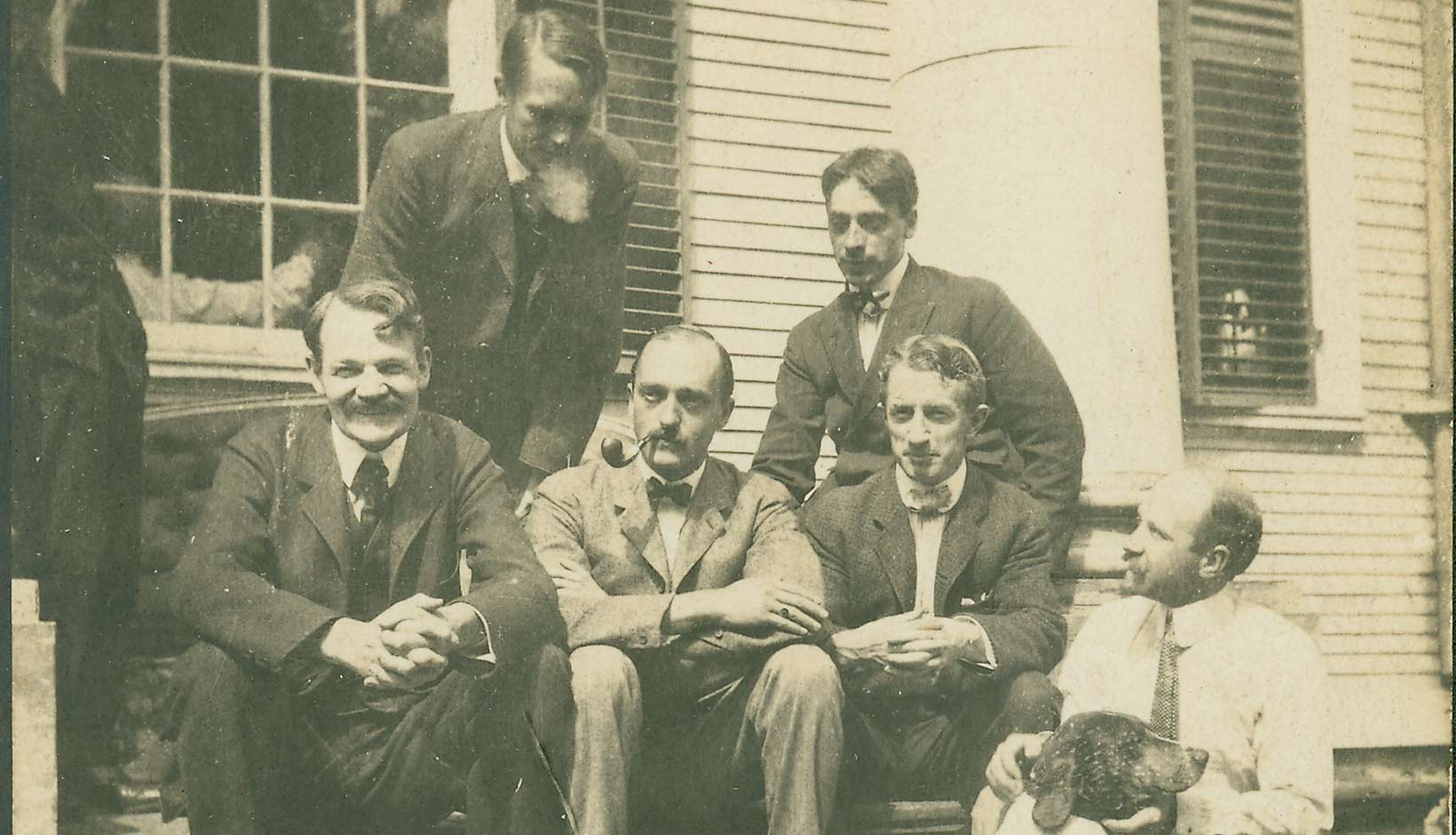

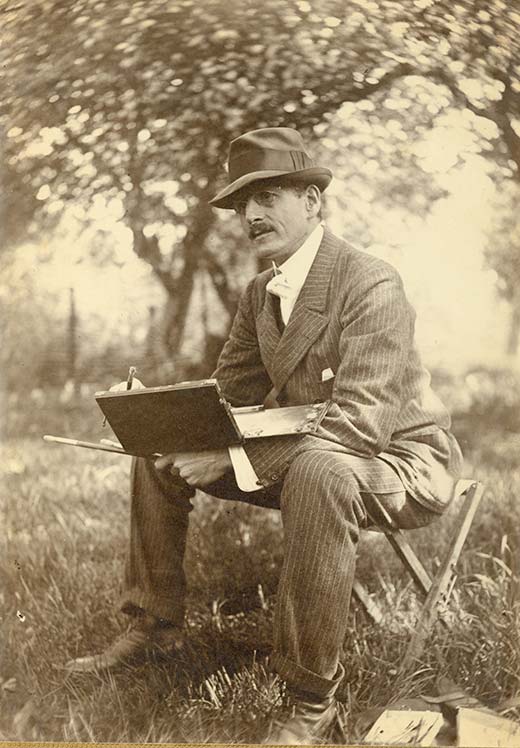

The Artists

Henry Ward Ranger is credited with being the first painter to stop at the Griswold boardinghouse, although artists had been passing along this section of the Connecticut shoreline for decades. Those that stayed with Miss Florence in her boardinghouse became known collectively as the Lyme Art Colony or “School of Lyme.” Despite the term “school” this group of artists were primarily professional painters who lived and maintained studios in New York. Many of them had studied art at renowned art academies in Philadelphia, Boston, or elsewhere. Most of the artists also traveled to Europe to complete their studies in places that were geared towards American students such as the Académie Julian in Paris before returning to New York to begin their careers.

Chadwick was known to hang a sign on the studio door

and was active during the first decades of the 20th century. Many of the Lyme painters knew each other from their time in school or while traveling in Europe. It was through their friendships and word of mouth that they encouraged each other to travel to Lyme to paint. Although the artists who came early to Miss Florence’s painted in a different style than those who came later, all the painters were interested in capturing the distinctly old-fashioned American subject matter Lyme had to offer. They were a like-minded bunch, for the most part, with the common desire to paint subjects that could be found in and around the small New England village of Old Lyme. This is what brought them together to Miss Florence’s boardinghouse.

Artists gathered on the front steps, c. 1905

Distinguished Guests

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States, was the most famous non-artist to stay at the Griswold boardinghouse. He came to Old Lyme along with his first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson, who was training to be an artist. During their first visit in 1905, the family stayed at another boardinghouse, but by 1909 Woodrow and his family were frequent guests at the Griswold House. Woodrow Wilson was the President of Princeton University during his first visits, after which he was elected Governor of New Jersey in 1910 and then President of the United States in 1912. Much of his political decision making happened while on holiday in Old Lyme between rounds of golf and communal meals enjoyed with the artists. The artists called him Colonel Wilson. About the artists Wilson remarked, “They are very easy to make friends with, — and I hope I am.”

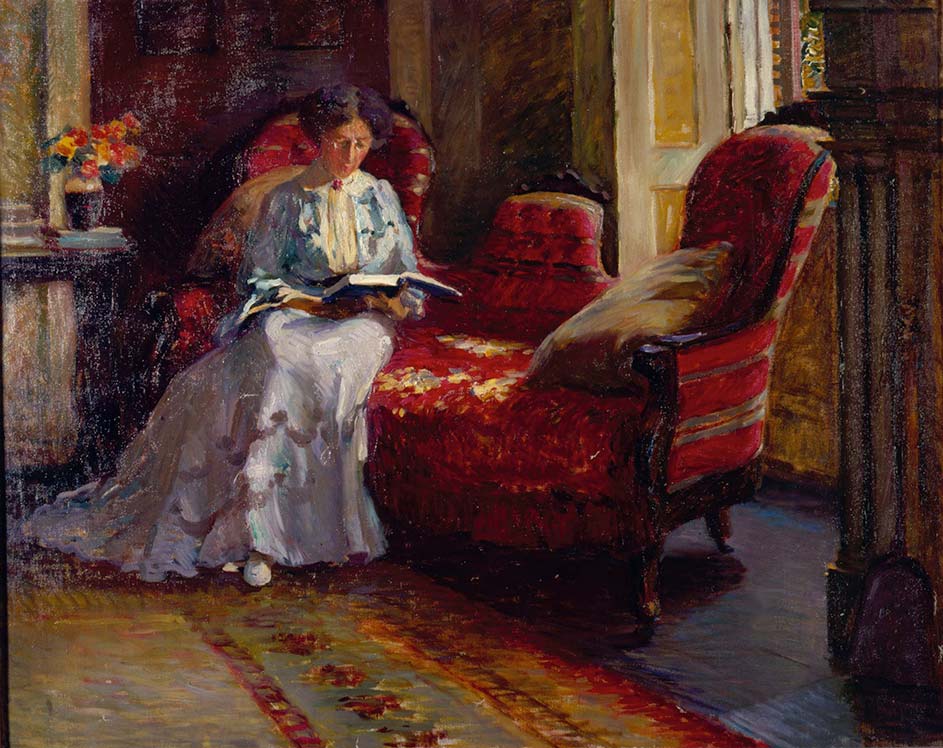

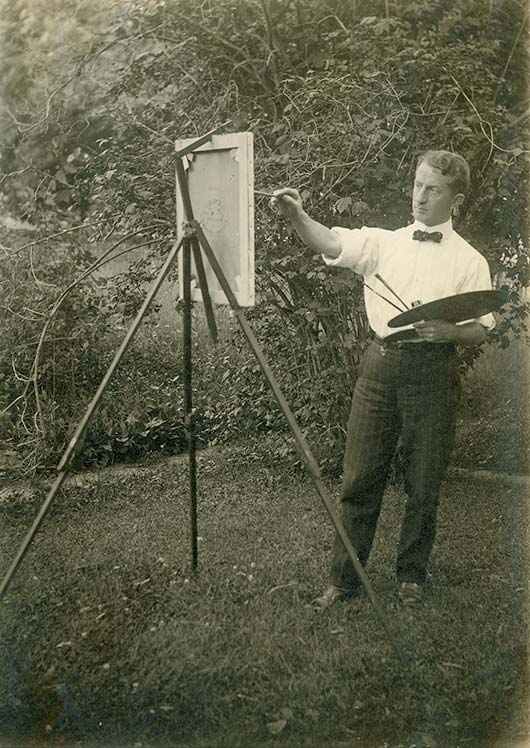

Ellen Axson Wilson

In Old Lyme, Ellen was treated more like an artist than the art student she was. Only professional artists were permitted to stay at the Griswold boardinghouse. Students and dilettantes could come for meals, but they needed to find housing elsewhere in the village. Her teacher, Frank DuMond also arranged for her to have her own studio, a luxury not available for most students. Despite her hard work, the artist William Chadwick remarked, “although Mrs. Wilson thought that she painted well, she was not really good.” Other artists staying with her at the boardinghouse commented that her work was “no longer that of an amateur” and that it was better than “a good deal of that in the exhibitions.”

The Wilsons’ three daughters,

Margaret, Jessie and Nell, often traveled with their parents to Old Lyme and became acquainted with the artists.

One summer, Jessie posed for the sculptor Bessie Potter Vonnoh for a small bronze statue. The three daughters are featured together in a painting by George Burr titled President Wilson’s Daughters (c. 1910) that was quickly rendered during a picnic excursion in Hamburg just north of Old Lyme. They are shown drying their swimming clothes and hair around a blazing bon fire. Years later, Margaret would invite Miss Florence to Washington, D.C., to be an honored guest at her wedding.

George Brainerd Burr (1876-1939) President Wilson’s Daughters Oil on panel Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Abraham Adler

Domestic Staff

Miss Florence was not alone in running her boardinghouse for artists. To help her with the daily operation of the house, she retained a small team of live-in domestic help comprised of a housekeeper, a cook, and a handyman. Most stayed for only a short time, the length of a season or a few years at best. The exception was the handyman James Kent who worked for Miss Florence for over 20 years. Like James, the female staff was largely of Irish descent taking advantage of the influx of workers immigrating to the United States from Ireland seeking work and religious freedom. The women lived in the small rooms on the upper floor of the back ell of the house. James was known to sleep in one of the barns, at least when there was limited space in the house. Although they were low paid workers, according to one of the artists, “they loved Miss Florence, and they stayed.”

There was a great deal of work to be done each day,

especially when the house was filled to capacity with over a dozen boarders. Working in a kitchen behind the main house, the cook would have been busy preparing the noontime and evening meals for the boarders, as well as those who came to the house just to eat. The fare was always ample, with a week’s menu consisting of a roast, turkey and ham, as well as shad, trout and salmon caught in nearby waters.

James, who “kept a beautiful garden going for the house,”

would harvest fresh vegetables and fruit from the gardens and ancient orchard. He was known to cut the grass after dark with an oil lantern tied to the handlebars of the mower to catch up on his endless list of chores. Working in unison with the cook, the housekeeper prepared the dining room for meals and tidied up the common areas of the house. Room service for the boarders was limited to a fresh pitcher of water daily and full kerosene lamps to light the way after dark.

Harry Hoffman (1874-1966) James, Oil on canvas Gift of the Artist

Most of what we know about the domestic staff comes from census records and fanciful memories of the artists.

The 1900 census list two servants in the house, the Irish-born Margaret Johnson, an illiterate widow of unknown age and Charlotte Eling, a 25 year-old single woman born in New York who was able to read and write.

Ten years later, the census lists Margaret Beckwith, a single woman aged 22 who was born in Connecticut, and James Kent is cited as a single, 41 year-old man “managing the farm.” The 1920 census lists two servants, Mary A. Holland, age 35, and Catherine J. William, age 27, along with Mr. Kent. Other records list a woman named Marie, on probation from the nearby women’s prison, Katherine Willis, a French Canadian who cooked for Miss Florence from 1921 to 1933, and a woman named Hannah McCabe.

The artists fondly remembered certain helpers who they nicknamed “Barefoot May” the cook, “Whistling Mary” the waitress, and “Old Kate, a “character and a privileged domestic” who one artist remembered “came thudding into the room to pass around the morning’s mail. She walked as though her feet had been amputated and she was treading on the stumps of her legs. So heavily did she pound around that she made the dishes and silverware jingle.” Less of a caricature is the figure of James, a large, “ruddy, dark haired, rugged looking” man who “wore overalls, boots, simple clothes” and rarely spoke although “he could quote reams of poetry,” who was dedicated to Miss Florence and continued his role of caretaker of the house even after she died in 1938.

Female Artists & Artists' Wives

The Lyme Art Colony counted few women among their ranks. In many ways, Old Lyme was a country version of the private art clubs the artists belonged to in Boston and New York. Likewise, the artists had an agreement with Miss Florence that they would review the applications of people who wanted to stay at the boardinghouse. They denied access to art students and dilettantes, but the families of artists were welcome as were a few female artists.

Party in the studio of Robert and Bessie Potter Vonnoh

Matilda Browne was one of the few female artists who were welcomed into the enclave of Miss Florence’s “boys.” She was the only woman to paint one of the doors in the boardinghouse – a charming scene of calves grazing beneath a tree. And she was the only woman depicted in The Fox Chase, albeit in a state of hysteria with arms raised in horror after discovering Childe Hassam naked from the waist up busily painting. In the artist colony she was later joined by the sisters Lydia and Breta Longacre, and the wife on one of the painters Bessie Potter Vonnoh, a respected sculptor.

Non-Boarding Guests

Through word-of-mouth, newspaper articles, magazine features, and citations in tourist guide books, the story of the Griswold boardinghouse where bohemian artists painted directly on the doors and walls began to spread. Such publicity brought tourists and townspeople to the boardinghouse where Miss Florence provided tours of the painted panels while sharing stories about the artists. She would eventually take advantage of the attraction and transform the center hall into a makeshift art and antique gallery and sell both new paintings created by her boarders, as well as New England collectibles to those passing through.

Art student along the Lieutenant River, c. 1904

Although these students were not permitted to rent a room in the boardinghouse,

on rare occasions they did take meals in the dining room. One newspaper account offers a hopeful student’s view on their denied access: “On passing the ‘Holy House’ we students bow in mock humility, each of us secretly hoping that some day we would be of enough importance . . . to be a resident there.”

Painted Panels

During the summer of 1900, the first for the art colony,

founding artist Henry Ward Ranger painted a picture on the outside of the door to the room he rented. This idea most likely came to him from his travels in Europe where this practice was common in the country inns frequented by artists. The notion quickly spread to the other doors on the first floor. In 1905, the painter Willard Metcalf suggested the artists line the walls of the dining room with individual wood panels to continue the tradition. An invitation to paint a panel was the utmost signifier that an artist was a welcomed guest at the boardinghouse and member of the colony.

The most elaborate panel is Henry Rankin Poore’s The Fox Chase, a long frieze-like painting across the fireplace that depicts the members of the colony in a mock fox hunt through the village. This prized collection of nearly 40 painted doors and panels quickly became an attraction that lured tourists to the boardinghouse. “Every stranger within the gates of Lyme wants to see it – and to see it is to admire it,” wrote one observer in 1914. Informal tours of the panels would be led by Florence Griswold herself, who would often conclude with a genteel sales pitch in the hall, which was outfitted as a make-shift gallery space to sell art colony paintings and local antiques.

To learn more about the painted doors and panels in the house, visit In-Situ: The Painted Panels.