Online Collections

Hartford Steam Boiler Collection

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm.

The paintings and sculptures in this exhibition are by artists who lived and worked in Connecticut from the late Colonial period to the early 20th century.

Connecticut has a distinguished artistic heritage, attributable in part to its location between the great cultural centers of Boston and especially New York. In many ways, its art has paralleled the course of American art, but artists have also responded specifically to Connecticut’s spirit of independence, its Yankee heritage, and the character of its landscape. Their visions have helped shape an identity of New England that lingers in the American mind.

Portraits came first in early America, but those in Connecticut were plainer than most, because sitters insisted. Landscapists bypassed Connecticut so long as romantic, grandiose views were the norm but came eagerly when rapid industrialization evoked sweet memories of America’s agricultural past. At the end of the 19th century, the sunny art of American Impressionism was pioneered in Connecticut. Artists came by the score to form art colonies, which flourished for nearly three decades. This exhibition takes Connecticut’s art history only that far, but artists in the state moved on to Modernism, Social Realism, and other newer modes.

The paintings on view are a gift to the Florence Griswold Museum from The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Over the course of two decades, this leading equipment breakdown insurer assembled 190 premier works of art by artists with Connecticut connections. In a magnificent act of corporate philanthropy, the company recently presented the collection to the Florence Griswold Museum – and thus to Connecticut and the nation. Less than half the collection can be exhibited now, but the entire collection of paintings, sculptures, and works on paper will inspire further exploration into the role of the American artist in Connecticut.

The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Insurance Company

The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company is a global provider of specialty insurance products, inspection services and engineering consulting.

Its roots as a Connecticut corporation date to the 1850s when a group of Hartford engineers expressed concern at the disastrous consequences of steam boiler explosions, a frequent occurrence of that day. In the wake of the 1865 explosion of the Mississippi River steamer Sultana, the worst boiler explosion in American history with a loss of 1,238 lives, they formed a company that would both inspect and insure steam boilers. Founded in 1866, Hartford Steam Boiler is one of the pioneering American businesses devoted to industrial safety.

As the company grew and matured, it became recognized for supporting industrial innovation through insurance and the application of new technologies. Today, Hartford Steam Boiler is one of the largest equipment breakdown insurers in the world. Among its more recent innovations has been the formation of collections of American paintings and furniture.

Wilson Wilde, the company’s President and CEO from 1971 to 1994, formulated a plan for preserving Connecticut’s heritage by collecting the works of Connecticut artists and artisans. Over a fifteen-year period, Hartford Steam Boiler acquired 70 pieces of furniture and 190 works of art, diversely representative of America, but unified by their association with Connecticut.

In 2001, Hartford Steam Boiler announced that it would donate its entire American art collection to the Florence Griswold Museum. Richard H. Booth, President and CEO since 2000, stated that “the collection embodies the values that made Connecticut a leader in building the nation – hard work, craftsmanship and excellence. This gift assures that the public will have full access to these works of art.” The Florence Griswold Museum is honored at having been trusted with the ownership and care of this collection. We hope you enjoy The American Artist in Connecticut: The Legacy of the Hartford Steam Boiler Collection.

Portraiture in Early Connecticut

By 1700, native and foreign-born artists alike were working in New England, but Connecticut saw none of them until the 1760s.

Families more middle than upper class had by then gained importance in virtually every town in the state and were ready to order portraits. Rejecting the elegant English style favored elsewhere by aristocratic families, they wanted to be seen as strong individuals who had achieved eminence not by birth but by character and work.

The first professional artist in Connecticut was William Johnston, who came in 1762 for a few years from his native Boston, where the gifted Englishman, Joseph Blackburn, was one of several influences. Johnston’s Connecticut patrons did not mind his obvious technical deficiencies, for he gave them the straightforward likenesses they wanted.

After the Revolution, the leading artist in the state was Ralph Earl, a Massachusetts native who visited several Connecticut towns in the late 1780s and early ‘90s and painted more than 100 portraits. To give his patrons the look of virtue, character, and industry they continued to demand, Earl tempered the refined style he had learned from Benjamin West in England while sitting out the American Revolution. His mix of primitive and sophisticated elements inspired local followers, who have become known as the Connecticut School. Among them are Mary Way, John Brewster, Jr., Harlan Page, and Ammi Phillips. Like Johnston and Earl, Brewster and Phillips had to travel from place to place in order to make a living, while Way and Page moved to New York City.

William Johnston (1732-1772)

Portrait of David Gardiner, Jr.

Johnston, the first professional artist to work in Connecticut, came to New London around 1762, and portrayed this 20-year-old man, his sister, and their parents, who were proprietors of Gardiner’s Island in Long Island Sound. Johnston had trained with his father, a Boston japanner, organ-builder, and portraitist, and he appears to have studied the Boston work of the Englishman Joseph Blackburn.

The pose, clothes, and oval format are sophisticated, but the face is a bit bloated and the eyes askew. Still, the look is straightforward and unpretentious, and that mattered most in Connecticut. Johnston was kept busy in New London, Hartford, and New Haven. By 1770, he had moved on to Barbados.

c.1762-63

Oil on canvas, 30 x 25”

Unsigned

Ralph Earl (1751-1801)

Mrs. Guy Richards of New London

Earl portrayed his New York City clients as genteel, worldly, and affluent. Connecticut people, however, wanted a look of modesty, piety, and republicanism. A New Englander himself, Earl understood, but his British training prompted him to add a bit of style.

In New London he painted six portraits of the Shaw family, including this one of Elizabeth Harris Richards (1727-1793). She holds Family Espositor: or, A Paraphrase and Version of the New Testament, a popular guide for family worship by the English Calvinist, Philip Doddridge. The window shows the wharf on the Thames River that her husband owned.

Miniatures of her son and his family are also in the exhibition.

1793

Oil on canvas, 43 x 32 3/4”

Signed and dated center left

John Brewster, Jr. (1766-1854)

Boy Holding a Book

Brewster was born deaf in Hampton, Connecticut, yet by his early 20s was literate, had invented a sign language, and was painting portraits. His early work followed Ralph Earl’s full-length format, but later he preferred the newly fashionable half or bust length, for which he charged $15. An itinerant painter, he moved his home base to southern Maine in 1796 but returned often to Connecticut.

By the early 1800s he had simplified his art and developed characteristics entirely his own. The compactness of form in this portrait, the boy’s expressive eyes, and the radiance around his head make Brewster one of the finest painters in early New England.

c.1810

Oil on canvas, 26 x 22”

Unsigned

Harlan Page (1791-1834)

Portrait of a Man

Art was never Harlan Page’s passion. Rather, this Coventry, Connecticut, house-joiner and schoolteacher worked tirelessly to convert everyone he came into contact with, first in his home state and then at the American Tract Society in New York City.

Page is identified with only two portraits. This one seems a visual representation of the Second Great Awakening, the dynamic 19th-century religious revival that set his soul on fire. “A glow of heavenly ardor burned in our brother’s countenance,” wrote his biographer. Is this a self-portrait?

c. 1815

Oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 18 3/4”

Unsigned

Ammi Phillips (1788-1865)

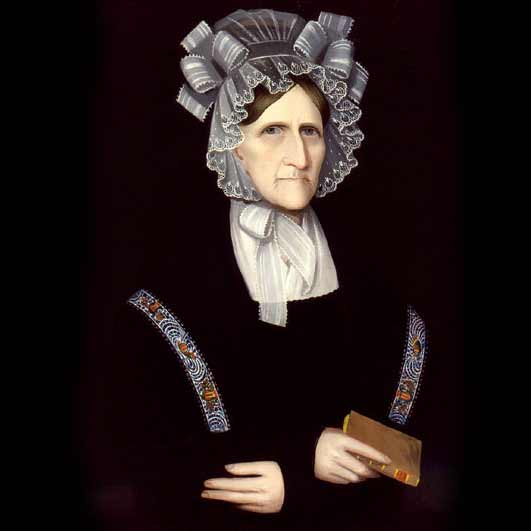

Portrait of Katherine Salisbury Newkirk Hickok

A native of Colebrook, Connecticut, Phillips is arguably the leading folk painter of 19th-century America. For years some 500 portraits were attributed to one of two Connecticut limners or painters. A signed work was discovered in 1958, and the genealogical research and stylistic analysis that followed led to the conclusion that Phillips was the Border Limner in the early years of his career and the Kent Limner in his later phase.

This portrait is from a period when Phillips was modeling faces with uncompromising clarity and highlighting dark clothes with a few striking decorations. He painted at least two other women wearing the bonnet that so smartly sets off this lady’s chiseled features.

c. 1825

Oil on canvas, 32 x 27”

Unsigned

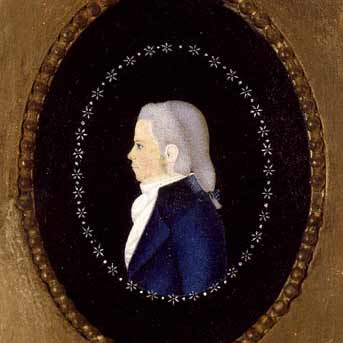

Mary Way (1769-1833)

Portrait of Peter Richards

Mary Way of New London is one of America’s earliest professional women artists. In the 1780s, she specialized in miniature watercolor portraits on paper or silk, which she usually “dressed” with cloth scraps or, as in these examples, with painted paper, applied as in a collage. These sitters — Peter (b. 1778) and Nathaniel (b. 1780) — were children of Guy Richards, Jr., of New London. They were still babies when Benedict Arnold’s forces devastated the city in 1781. The family business was burned, and their home was saved only because the boys’ sister lay ill inside.

See miniatures of their parents and Ralph Earl’s portrait of their grandmother elsewhere in the exhibition.

1780s

Watercolor on silk with paper collage,

2 3/4 x 2 1/2”

Unsigned

Mary Way (1769-1833)

Portrait of Nathaniel Richards

Mary Way of New London is one of America’s earliest professional women artists. In the 1780s, she specialized in miniature portraits on paper or silk, which she usually “dressed” with cloth scraps or painted paper. Peter (b. 1778) and Nathaniel (b. 1780) were children of Guy Richards, Jr., of New London. They were still babies when Benedict Arnold’s forces devastated the city in 1781. The family business was burned, and their home was saved only because the boys’ sister lay ill inside.

See Ralph Earl’s portrait of their grandmother elsewhere in the exhibition.

1780s

Watercolor on silk with paper collage,

2 3/4 x 2 1/2”

Unsigned

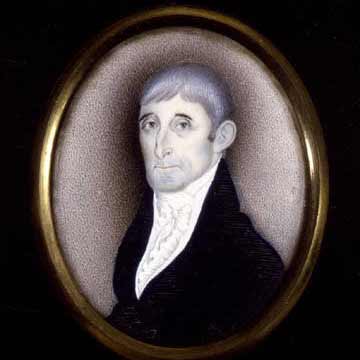

Mary Way (1769-1833)

Portrait of Mr. Guy Richards

Guy Richards was the treasurer of New London, and Hannah was his wife. These portraits, attributed to Mary Way, probably date from before 1811, when the artist moved to New York City. She worked in the male-dominated art world until 1820, when she was blinded by glaucoma. John Trumbull and Samuel Waldo, leading artists and fellow Connecticut natives, organized a benefit exhibition for their “sister of the brush.”

Watercolor on silk, 2 3/4 x 2 1/2”

Unsigned

Mary Way (1769-1833)

Portrait of Hannah Dolbeare Richards

Guy Richards was the treasurer of New London, and Hannah was his wife. These portraits, attributed to Mary Way, probably date from before 1811, when the artist moved to New York City. She worked in the male-dominated art world until 1820, when she was blinded by glaucoma. John Trumbull and Samuel Waldo, leading artists and fellow Connecticut natives, organized a benefit exhibition for their “sister of the brush.”

Watercolor on silk, 2 3/4 x 2 1/2”

Unsigned

Lucius Barnes (1819-1836)

Mrs. Martha Atkins Barnes

Creating a likeness of his 96-year-old grandmother was a monumental challenge for Barnes, a paralyzed Middletown teenager who could move only his hands and toes. He made at least seven profile portraits of her. She wears the same glasses and clothes in all but stands smoking a pipe and leaning on a cane in some and sits with a Bible in others. Crude though they are, they are vivid depictions of a strong, confident woman.

1834

Watercolor and ink on paper, 4 1/2 x 3 1/2”

Signed lower right

Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872)

Louisa W. B. Hughes

He had already painted miniatures while at Yale, but the future inventor of the telegraph polished his elegant style under Washington Allston in this country and in England. Morse yearned to produce monumental allegories and history paintings that would elevate public taste, but the America of his day did not regard painting and sculpture as necessities of life. Furthermore, the new Hudson River School landscapes made history painting seem old-fashioned. Morse worked at portraits in New Haven, Hartford, and New York City for a number of years but gave it up in mid-life, saying that art had given him a cruel jilt.

Oil on panel, 8 1/2 x 6 1/2”

Inscribed on verso

Discovering the Connecticut Landscape

Most artists who worked in Connecticut in the 19th century were well trained and came from other places. Their landscape paintings celebrate a peaceful and unpretentious countryside. More than a bit of nostalgia was involved, however, for Connecticut was already on the way to becoming more suburban than rural.

In the 1830s, when American artists moved from topographical views to grand vistas, they sought out wilderness areas and sublime wonders such as waterfalls, virgin forests, and natural bridges. No matter what the site, this romantic and often symbol-laden art came to be called the Hudson River School. Rarely does it depict Connecticut. When artists began traveling to the spectacular American West, Connecticut’s gentle landscape, where wilderness had long since given way to farms and villages, continued to be ignored. After the Civil War, however, when the concept of Home entered the American psyche as never before, Connecticut came into its own.

Connecticut’s domestication was now its charm. Its stone walls, fences, white church spires, old houses, roads, and streams are in the new landscape paintings. The state’s iconic tree, the Charter Oak, appears to abut common farmland in Frederic Church’s painting of it, for the artist chose to ignore a mansion at the downtown Hartford site. New Haven’s monumental West Rock, important in Colonial history, is a backdrop for agrarian scenes in paintings by other artists, such as Benjamin Coe, who was Church’s first teacher, and George Durrie. Moreover, artists painted views in Connecticut that were markedly different from the dramatic work they did elsewhere, as when Worthington Whittredge and George Loring Brown, leading chroniclers of the American West and of Europe, painted cabbages in Simsbury and oystering in Norwalk.

Frederic E. Church (1826-1900)

The Charter Oak at Hartford

The Charter Oak is a symbol of the spirit of independence that began the American Revolution. In 1687 Connecticut stood alone in New England in defying James II’s orders to relinquish a 1662 charter that had given the colonies a degree of self-government. Legend has it that candles went out suddenly at the showdown meeting and the charter vanished – into a hole in the ancient oak down the street – and so the king’s deputies were foiled. Frederic Church of Hartford, Thomas Cole’s only student, became the leading American landscape painter of the mid-19th century. He painted this Connecticut icon early in his career and chose not to show the famous cavity or the Wyllys family mansion at the site. His tree dominates a flourishing Connecticut landscape, like those that would soon be celebrated by other artists.

Oil on canvas, mounted on masonite,

24 x 34 1/4”

Signed lower left

George H. Durrie (1820-1863)

Summer Landscape

Fellow Hudson River School artists generally painted pure landscape, but New Haven’s Durrie was one of the first to show that the Connecticut countryside had inhabitants, who were nurtured by the land. In the 1700s, American artists depicted farms as visual inventories of a farmer’s possessions. A century later, Durrie shaped the same elements into a landscape setting that affects people physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

His idylls seemed faithful representations of 19th-century rural New England to many who saw Currier & Ives prints of his work. Some people must have known that he was painting a lovely myth, but only art critics seemed to mind.

1862

Oil on canvas, 22 x 30”

Signed and dated lower left

John Williamson (1862-1885)

Wallingford, Connecticut

Williamson lived in Brooklyn, New York, but most likely he visited Wallingford on his way to or from northern New England. This scene is more intimate and has a closer viewpoint than his other paintings.

The trees that dominate in so lively a manner are a reminder that Williamson was also a fine still-life painter, who depicted flowers growing outdoors in the Pre-Raphaelite manner advocated by the Englishman John Ruskin. The painting’s size, brushwork, and clarity of light indicate that it was almost certainly painted outdoors. The spirit of place is palpable, and is underscored by the inscription at lower right.

1867

Oil on canvas, 10 1/4 x 16 1/4”

Inscribed, signed and dated lower right

Marie Theresa Gorsuch Hart (1829-1921)

View on the River, Farmington

Marie Theresa Gorsuch, a Baltimore native, spent the summer of 1865 in Farmington painting with the prominent New York artists James Brevoort and James McDougal Hart. In August, the announcement of her engagement to Hart thrilled the village. The two married the next year.

This painting exemplifies the preference of the late Hudson River School for closer viewpoints and smaller, more humanized scenes. The hushed air of tranquility in such paintings may be linked to the nation’s collective sigh of relief when the Civil War finally ended. After her husband’s death in 1901, the artist lived out her very long life in Lakeville, Connecticut.

1866

Oil on canvas, 10 3/4 x 20 1/8”

Signed and dated lower left

George Loring Brown (1814-1889)

Norwalk Island

For years Brown lived in Italy where his lush scenes of ruins and mountain lakes were popular with both Americans and Europeans. In the early 1860s, he returned to his native Boston and visited Connecticut to paint views of the Norwalk Islands.

These paintings differ sharply from his Italian work. The subject matter is homier, the viewpoint closer, the colors brighter, and the light clearer. Brown’s custom in Italy of using color patches to emphasize effects of light and dark is seen here only in the foreground. Other areas such as the pole with a pennant, marking an oyster bed are closely observed. A note on the back says that this scene was painted outdoors.

1863

Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 14 1/2 x 21”

Signed and dated lower right

John F. Kensett (1818-1872)

Shore of Darien, Connecticut (Long Island Sound from Fish Island)

In 1867, Kensett, a Connecticut native and well-known Hudson River School painter, bought land on Contentment Island near Darien. The realism of his early work had already given way to a greater emphasis on the effects of light. Now Kensett developed an aesthetic that blended accurate observation with spare compositions, low-key colors, and nuances of atmosphere and light.

He painted this scene (and himself doing so) on Fish Island near Contentment. Dazed by the Civil War and the nation’s rampant industrialization, Americans were looking to nature for solace. Kensett’s art had a spiritual serenity that they appreciated.

1872

Oil on canvas, 12 x 20”

Signed lower right

David Johnson (1827-1908)

View near Greenwich, Connecticut

A picturesque fishing scene is marred by a train in the distance. Did the artist realize that the railroad would shortly end fishing as an occupation here and all but destroy this tranquil place? The artists who followed him to the area in the 1890s were confronted by more telling evidence than that hinted at in his painting.

Johnson, a late Hudson River School artist, painted at least six Greenwich and Cos Cob scenes between 1878 and 1889. He was in the area as early as 1869, when he made a view of a Greenwich estate owned at the time by the infamous “Boss” Tweed.

1878

Oil on board, 13 7/8 x 19 3/4”

Signed and dated lower right

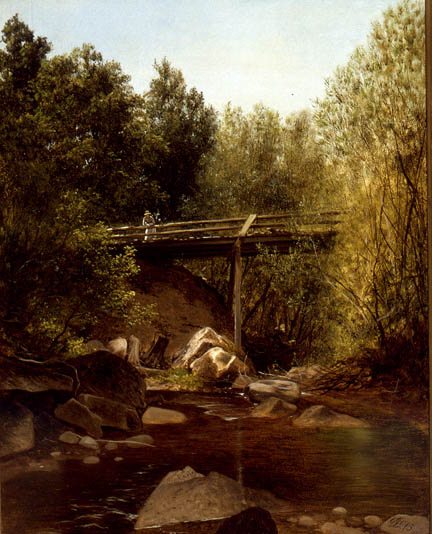

David Johnson (1827-1908)

West Cornwall, Connecticut

Johnson, a New Yorker, was a prolific painter who worked not only at home but in Virginia, New Jersey, and all six New England states. In Connecticut he painted in Greenwich and Litchfield County.

His rustic West Cornwall Bridge looks barely functional. That its single vertical support merges uneasily with its liquid reflection adds to the feeling of fragility. The boulders, scattered by glaciers centuries before, and the more recently fractured tree trunks, speak volumes about the power of nature. Reverence for nature was an idea well fixed in the national consciousness.

1875

Oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 13”)

Signed and dated lower right

John Ludlow Morton (1792-1871)

View of the School House at Greens Farms

This Adams Academy schoolhouse, which still stands, was just three or four years old when Morton, a well-established portrait, history, and landscape painter, depicted this scene. A lifelong New Yorker, Morton appears seldom to have ventured beyond the Hudson Highlands. He may have visited Greens Farms, near Southport, Connecticut, to see why it had become a popular resort. The school held summer sessions that were well attended by the vacationers’ children. Morton juxtaposed sedate scholars (was any school recess ever so calm?) and fellows going to or coming from a shoot in a sporty open carriage, their high spirits reflected in the buoyancy of their horses and dogs. Lush farmland is in the background here. This Connecticut place is mainly for schooling and sport.

c. 1840

Oil on canvas, 18 x 24”

Signed and inscribed on the reverse

Fidelia Bridges (1835-1923)

Thistle in a Field

Bridges made precise renderings of flora and fauna in their outdoor settings, so she needed to paint in the open air for hours at a time. Custon required her to dress and behave there as though she were at home in her parlor. Women artists were not allowed to be “bohemian.”

This oil, a departure from her usual medium of watercolor, was probably done in Stratford, Connecticut, where Bridges often summered in the 1870s. Her work was exhibited widely, and she was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design. She spent her last years in Canaan, Connecticut.

1875

Oil on canvas, 14 x 10”)

Signed and dated lower right

Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910)

A Farmer’s Garden in Simsbury

Whittredge, a Hudson River School and Western artist, painted this Simsbury scene in about 1860, while visiting a patron. The canvas is bed ticking, so he may not have come intending to paint. The work is a sharp departure for him both in subject matter and design. Perspective lines stop short of the horizon. The cabbage row rushes the eye to the convergence point, then up a tree to the sky, while the line of trees exerts a counter thrust to the right.

Three decades later, Connecticut Impressionists would regularly create designs that play fast and loose with traditions about focal points, symmetry, and spatial depth. In Simsbury, Whittredge may have been in a holiday mood that inclined him to experiment.

c.1875

Oil on canvas, 15 x 9 5/8”

Signed lower left

Henry Pember Smith (1854-1907)

Old Homestead on the Turnpike

Smith, a Waterford native, often depicted Venetian palazzos but returned to Connecticut to paint idyllic country scenes. Several are strikingly similar, including a Dutch Colonial house, a dooryard with stone wall or fence, sheltering trees, and ducks or geese ambling down a dirt road. Clearly, this image struck a chord with the public or Smith could not have sold so many variants of it.

Americans were exulting in the belief that the nation would become a world power but worried that the principles of the Founding Fathers might erode as a result. Old homesteads had survived, went the thinking, and so, too, would America’s independent spirit if people held fast to the old values.

c. 1889

Oil on canvas, 12 x 16”

Signed lower left

Nelson Augustus Moore (1824-1902)

Apple Orchard

This Kensington, Connecticut, native referred to himself professionally as N. A. Moore. He wanted to work mostly in his native state, but he needed to move about in order to make a living. He had given up a flourishing daguerrotype business in Hartford in order to paint full-time. For more than 20 years he summered at Lake George, New York, where tourists ordered large versions, to be delivered later, of the small oil sketches he painted and showed them there. If he had enough orders to keep busy all winter, he went home to Kensington. If not, he set up winter studios elsewhere, often in Hartford but sometimes in New York and other large cities. Hartford claimed him as a local artist whenever he was there. He painted many pastoral views of the Connecticut landscape.

1878

Oil on canvas, 18 x 28”

Signed and dated lower left

Still Life & Genre

In the mid-19th century, still-life and genre paintings, with their everyday subject matter, were popular in America.

Several Connecticut artists specialized in them. Without the need to move about, as early portrait and landscape painters had done, they established “show” studios in order to display their paintings and develop a local clientele. Often that meant that they were not well-known outside the cities where they worked. Several artists of distinction, however, have been rediscovered in recent years.

Hartford’s Gurdon Trumbull ignored the custom of painting a fisherman’s catch and portrayed instead fish who are fighting to live. John Haberle of New Haven incorporated humor and irony into his fool-the-eye still lifes. The art of Charles Ethan Porter, a fruit and flower painter, was admired by Mark Twain and Frederic Church, a major achievement in itself, but Porter was also an African-American. Despite the odds against it, he studied and exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York and had a long career in Connecticut.

Edwin White and John Morton were painting genre scenes in this state as early as the 1840s. They were here only briefly, but George Durrie spent his life in New Haven painting landscapes that verge on genre. Lithographs of Durrie’s paintings, which were issued by Currier and Ives, helped create a lasting image of rural New England. In the village of Morris, Connecticut in 1885, William Lippincott saw American women as prettier and gentler than their Colonial predecessors, with leisure for art and literature. His painting foreshadows the theme of the contemplative woman, which was prominent in American art at the end of the century.

Edwin White (1817-1877)

The Fisher Boy

White was an early genre and history painter. He was born in South Hadley, Massachusetts, and apparently had no formal art training until he came to Hartford at age 18 and studied with Philip Hewins, a portrait painter. Within a few months he had a commission to paint a Madonna in Norwalk. He opened a studio in Bridgeport in 1840, the year The Fisher Boy was painted, and began exhibiting at the National Academy of Design. Convinced that he needed to learn more, he moved to New York soon after. Later he went abroad to absorb the work of the European masters.

1840

Oil on canvas, 30 x 22 1/2”

Signed and dated lower right

Gurdon Trumbull (1841-1903)

Black Bass

In Hartford, Trumbull painted fish so full of life that he was called the finest fish painter in America. Images of a fisherman’s catch were common in the 19th century, when fishing became a sport. Few besides Trumbull, however, could convincingly paint fish swimming in water. Critics were agog at his “uncommon union” of live action and minute detail.

Trumbull’s work is rare not only for its artistry but also because he painted very little. The artist was wealthy, and he did not need to work. As spirited as the fish he portrayed, he abruptly ended his art career to pursue other interests, among them collecting china.

1872

Oil on canvas, 17 1/2 x 25 1/8”

Signed and dated lower right

John Haberle (1856-1933)

The Clay Pipe

The New Haven, Connecticut, artist John Haberle specialized in still-life paintings of mundane objects rendered with incredible realism—a style known as trompe l’oeil, or “fool the eye.” Here, an old-fashioned clay “churchwarden’s” pipe with a long stem hangs from a worn wooden panel next to a pouch of tobacco. Despite such seemingly straightforward realism, Haberle’s still lifes often subtly allude to contemporary issues or philosophical considerations about illusion and reality. The brand of tobacco depicted here has been identified as “Duke’s Mixture,” a variety so inexpensive that it was said to be made of factory floor sweepings. Around this time, the phrase “duke’s mixture” entered American English as an expression meaning an odd combination or chaotic, confused situation. Haberle may be playing on the baffling nature of trompe l’oeil painting itself, a “duke’s mixture” that tempts viewers to question what they see.

c. 1890

Oil on canvas, 18 x 8 3/4”

Signed lower right

Charles Ethan Porter (1847-1923)

Peonies in a Vase

Porter was one of very few African-American artists of his day. In 1881 he auctioned his paintings in Hartford to finance study in Paris, an experience that American artists deemed essential. He enrolled at the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs and stayed in France for three years.

On his return to Hartford, he demonstrated new technical virtuosity in paintings such as Peonies in a Vase. It soon became clear, however, that

Hartford preferred Porter’s earlier more primitive and meticulous art. A nationwide economic turndown and mounting racism added to his burdens. Finally, he went home to Rockville, Connecticut, where he continued to paint, teach, and exhibit.

c. 1885

Oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 23 1/2”

Signed lower right

Charles Ethan Porter (1847-1923)

Strawberries

Done after Porter studied in France, this painting recalls one that this African-American artist painted a decade earlier. He had studied and exhibited at the National Academy of Design and painted in New York City before settling in Hartford in 1878. His meticulously detailed fruit paintings had dazzled Hartford then.

Porter’s art was impressionistic just after his return from Paris in 1884. Hartford, however, preferred the earlier still lifes. This painting must have been done to please. It is lightly edited–fewer berries and leaves–but otherwise a near twin to the 1870s painting.

1888

Oil on canvas, 12 x 16”

Signed and dated lower right

William H. Lippincott (1849-1920)

Summer Afternoon, Morris, Connecticut

A New Yorker, who had become a skilled genre painter during a stay in France, Lippincott spent a summer in Morris, near Litchfield. Artists had been visiting the Connecticut countryside for some time, alone, with family, or a friend or two. Art colonies were yet to be established here.

These women are enjoying the recreational pursuits recommended for them in late 19th-century America. Watercolor painting was at the height of its appeal, both for professionals and hobbyists. Books continued to be seen as uplifting. As technological advances and an immigrant labor pool made it easier to run a household, leisure became a reality for the middle classes.

1885

Watercolor on paper, 14 x 20”

Signed and dated lower right

Edward S. Bartholomew (1822-1858)

Sappho

Bartholomew, a Colchester, Connecticut, native, intended to be a painter until about 1845, when he realized that he was colorblind. He had been caring for the art collection at the new Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, the nation’s first public art museum.

Sculpture became his new passion, and he moved to Italy in 1850 to pursue it. The base of this Neo-classical marble of a famous 7th-century Greek woman poet is marked “Rome.” Bartholomew later moved to Naples, where he died at the young age of 36.

1850s

Marble, 25” x 16” x 14”

Signed back of base

Connecticut & American Impressionism

In the 1890s, Connecticut led the way in creating American Impressionism, chiefly because of John Henry Twachtman and J. Alden Weir, who worked together in Greenwich and Branchville. Their friends Childe Hassam, Theodore Robinson, and Willard Metcalf arrived soon after and did some of their best painting in Connecticut.

These five are undisputed masters of American Impressionism. Hundreds of other artists came to work and learn, primarily at Cos Cob, Old Lyme, and Mystic. Cos Cob was the first Impressionist art colony in America. Old Lyme became the largest and best-known.

Their French predecessors had celebrated modern life, but the artists who loaded paint boxes and easels onto trains in New York City were fleeing urbanism in times of disturbing change. They found refreshment in Connecticut’s civilized landscape and reassurance that the Yankee values of the country’s founders would endure. These American artists had trained in the best European schools and were inspired by painters as diverse as Hals, Velasquez, Millet, Manet, Monet, and Whistler.

They were excited by the decorative asymmetric designs of Japanese prints. Selecting and modifying freely, they sought to capture not so much a moment as character and essence. Working in the open air, they flooded their canvases with light, laid on bright colors, and abandoned techniques that had for centuries given the illusion of solidity and depth. Their portrayals of the Connecticut landscape were designed not as reproductions but as expressions of their innermost feelings. Boston artists would develop an Impressionism that centered on people. In Connecticut the focus was place.

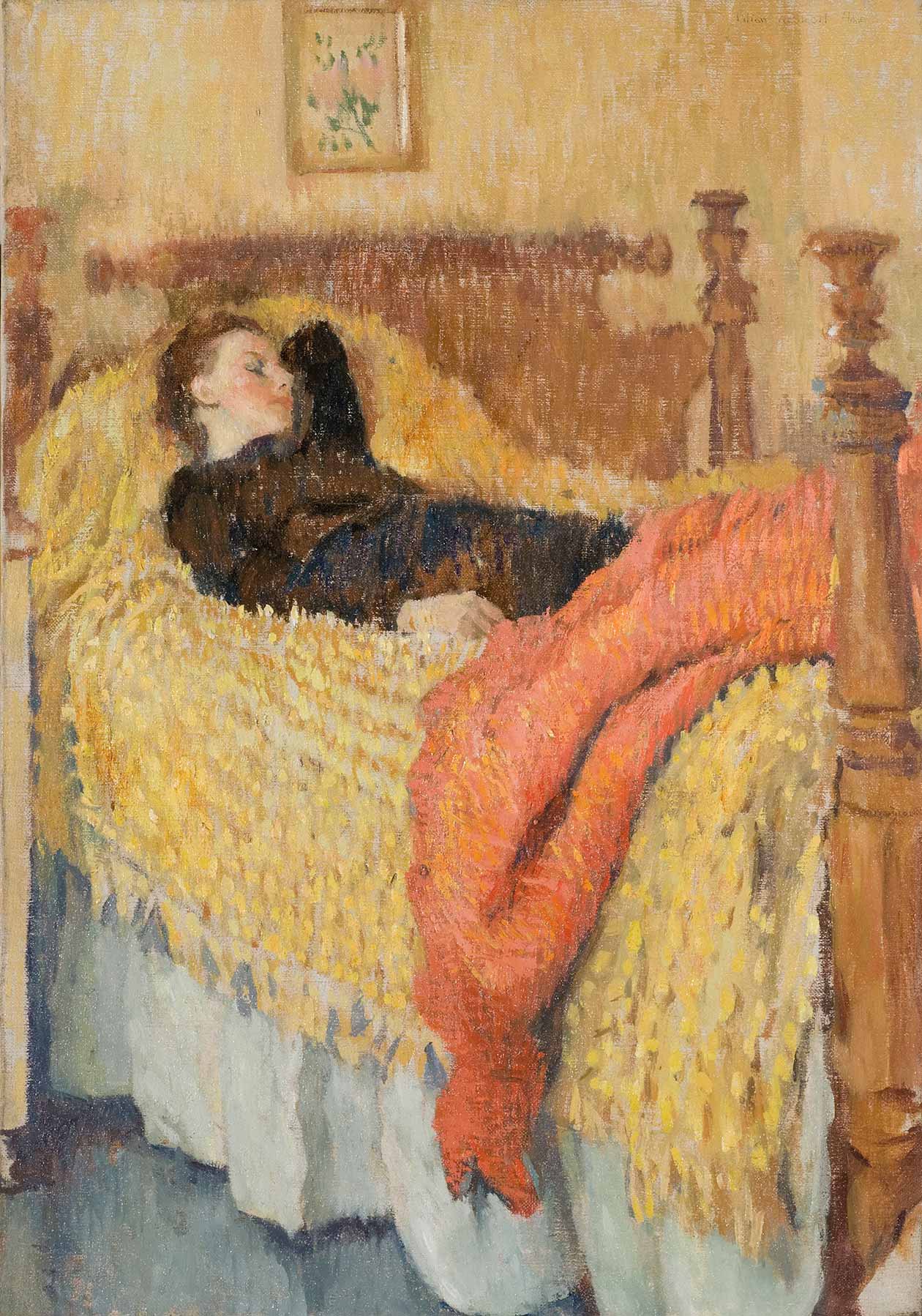

LILIAN WESCOTT HALE (1880-1963)

Woman Resting

Lilian Westcott studied at the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston on a scholarship from the Hartford Art Society. She married her teacher, Phillip Hale, and became a mother yet managed to have a serious and successful career as an artist. It was an uncommon story in her day.

A century earlier, a picture like this would have been unthinkable. Not only had attitudes toward women undergone a sea change, but so had art. Whether in interior views or landscapes, American Impressionists wanted their pictures to be intimate and inviting. Close viewpoints, off-center compositions, cropped edges, compressed space, bright colors, and sketch-like brushwork were among the ways in which they achieved their goals.

c. 1920s

oil on canvas, 20 X 14″

Signed upper right

THEODORE ROBINSON (1852-1896)

Autumn Sunlight (In the Woods)

Robinson, a Vermont native, painted this scene in France, perhaps at Giverny, where he was a friend of Claude Monet. The woman recalls the peasants of Barbizon art but confronts us as they do not. Women who appear to blend with a natural setting are seen often in American Impressionism. In Cos Cob, Robinson would instead paint some strikingly modern shoreline scenes.

He and his friends J. Alden Weir and John Twachtman introduced their students to Monet’s theories. Once it was taught in the art schools, Impressionism spread rapidly across America in a variant that remained mindful of native traditions and motifs.

c. 1888

oil on canvas, 18 1/8″ x 21 3/4″

signed and dated lower right

John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902)

Connecticut Shore, Winter

Twachtman, leader of the art colony at Cos Cob, did not develop his mature style, for which he is best known, until after he painted this scene. This is probably the harbor at Bridgeport, where he first worked in 1888. In Munich he had developed a bravura manner with lights and darks. A paler-colored period of refined Whistlerian abstraction followed.

This painting retains the asymmetrical design favored by Whistler and the Impressionists but is painted directly with a spontaneous, self-assured verve that boldly summarizes the bulk and rigging of the ships. Connecticut Impressionists were keenly aware of seasonal changes, and several painted winter scenes. Many of Twachtman’s finest landscapes are snow pieces.

c. 1889

Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 x 30”

Signed posthumously lower left

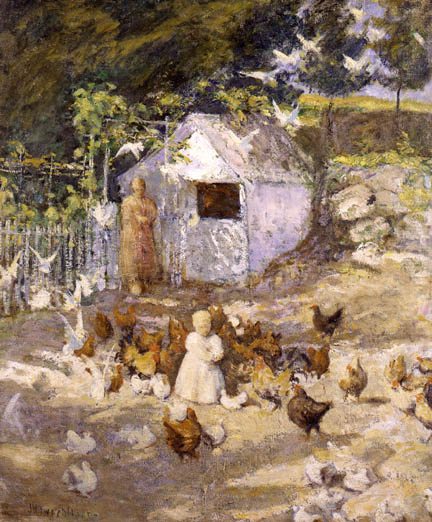

John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902)

Barnyard

Home and family were precious to late 19th-century Americans, and artists often portrayed them. Twachtman’s little daughter is watched by her mother, whose brown dress links her to the earth, while lattice frames her like an icon in a niche. Doves recall the Holy Spirit, and splashes of bright light can be seen as the light of grace. The artist does not insist upon a religious reading but subtly suggests it.

Chickens and doves were considered as necessary to the commuter’s household as to the farmer’s. Caring for them was often the province of children, because poultry-keeping was seen as a character-building activity.

c.1890-1900

oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 25 1/8”

signed lower left

Emil Carlsen (1853-1932)

Night, Old Windham

A superb still-life painter, Danish-born Carlsen became a landscapist as well when he began summering in Connecticut in 1896. At first he stayed at artist J. Alden Weir’s place in Windham Center, in the east. From 1905, he had his own home in Falls Village, in the northwest.

The cottage depicted here is probably the one that Weir lent the Carlsen family for several summers. Connecticut Impressionists often painted moonlight views. Childe Hassam gave continuing rain as one reason. Night scenes were, of course, done indoors.

1904

Oil on canvas, 50 1/2 x 40”

Signed and dated lower right

J. Alden Weir (1852-1919)

Windham from Mullins Hill

Weir’s pioneering Impressionist landscapes are seldom superficially attractive. In this one, trees and poles “float” like those in some prints by Hiroshige. The big tree, pathways, scythe, and cloud seem odd and distracting. Astute critics saw that Weir’s quirky compositions, unkempt brushwork, and low tones were done with a sure touch, singleness of aim, and absolute truthfulness. He painted some of the masterworks of American Impressionism.

Windham, where his wife’s family lived, was the first Connecticut village Weir saw. When he inherited the place, he had two Connecticut farms. The one in Branchville is now a National Historic Site.

c. 1895

Oil on canvas, 24 x 20”

Signed lower right

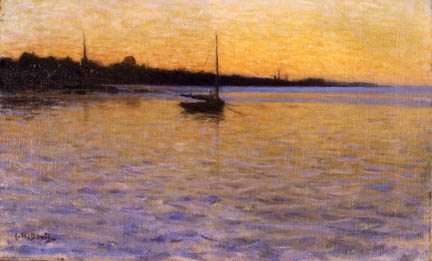

Charles H. Davis (1856-1933)

Summer Uplands

Two views were dear to Davis: hillsides with only a bit of sky and big skies with only a little land. Few artists of his day painted clouds with so great a presence and so strong a sense of movement.

Davis’s work was much admired. He never had a New York studio, yet his paintings were sought after by galleries and museums and were in major exhibitions. Altogether, Davis painted some 900 landscapes in Mystic. Supposedly, he had come because Mystic was a good place to sail a boat. It was also a good place for him to paint.

Oil on canvas, 36 x 29”

Signed lower left

The Cos Cob Art Colony

In about 1890, John Twachtman, who had settled in Greenwich, began offering summer classes in landscape painting at a boarding house that welcomed artists.

It belonged to his friends the Holleys and overlooked the harbor in the Cos Cob section of town. J. Alden Weir visited from Branchville and sometimes shared the instruction. Theodore Robinson came from Giverny and twice stayed for weeks. Childe Hassam was in and out for nearly three decades. For several years, Genjiro Yeto was there to explain Japanese art and culture. By 1895 Twachtman’s Greenwich farm had become “a regular rendezvous for Impressionists,” and the Holley House (now the Bush-Holley House and a museum) was home to the first Impressionist art colony in America.

Artists loved the Cos Cob experience. Besides shore and sea views, there were woodlands, pretty roads, and backcountry farms. In the tiny village, the painters mixed with fishermen, shipbuilders, and farmers. Pre-Revolutionary houses, including a section of the Holley House itself, were clustered at the water’s edge.

Twachtman stopped teaching in 1899 but lived at the Holley House from the fall of 1901 until shortly before his death the next year. The colony might also have died then but for Elmer Macrae, a Twachtman student married to a Holley daughter, who kept things going for two more decades. The Greenwich Society of Artists formed in 1911. Altogether some 90 artists were active at Cos Cob, as well as dozens of students, but Cos Cob also attracted writers, like Lincoln Steffens, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Willa Cather, and performing artists. It made for a stimulating mix in a Connecticut town just sixty-some minutes from Broadway

John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902)

Horseneck Falls, Greenwich, Connecticut

Twachtman knew at first look that a farm on Round Hill Road in Greenwich was for him. By 1889, this Cincinnati native had given up his New York studio and was living in Connecticut year-round and commuting to teach at the Art Students League in New York. He remodeled the house, planted gardens, and, happily for American art, painted his property again and again.

Horseneck Falls, a series of small cascades in the brook near his house, appear in several paintings. Although this landscape may seem natural, the two young trees are so carefully spaced that they were almost certainly planted. This scene artfully balances unspoiled and cultivated nature.

c. 1890-1900

Oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 25 1/4”

Unsigned

Dorothy Ochtman (1892-1971)

Still Life with Kettle

The daughter of prominent Cos Cob landscapist Leonard Ochtman and portraitist Mina Fonda Ochtman, Dorothy Ochtman made still-life her speciality. She studied with Dwight Tryon at Smith College and afterward at the National Academy of Design. Her awards include one in 1924 for a painting with the same teakettle as the one here and a similar background of closely related tones and impressionistic broken brushstrokes. Three blue-green designs on the background resemble James Whistler’s butterfly signature, so perhaps Ochtman intended a subtle homage to the expatriate American whose “arrangements” influenced the American Impressionists. The delicate Asian porcelains and the sturdy kettle are an eclectic pair, conveying her love for a beauty both exotic and humble.

c. 1925

Oil on canvas, 28 1/4 x 24”

Signed lower left

J. Alden Weir (1852-1919)

Silver Chalice, Japanese Bronze and Red Taper

This is private picture. Weir owned the Renaissance chalice but its connection with the bronze and taper is unclear, and not enough is seen of the painting behind them to recognize it. The picture mat at the left, however, bears James Whistler’s signature and his famous butterfly mark, and since Weir’s painting style here emulates the famous expatriate’s to some extent, he may have intended this painting to be a tribute to Whistler.

The very intimacy, however, both in the choice of objects and in the odd composition and tight viewpoint, prefigures the intensely personal way in which Weir and other Impressionists would respond to the Connecticut landscape.

c.1884-1889

Oil on canvas, 17 1/8 x 11 5/8”

Signed upper right

Carl Schmitt (1889-1990)

Pumpkin with Iron Pot

Schmitt, an Ohio native, was one of the “Knockers” who met weekly in the Silvermine, Connecticut, studio of sculptor Solon Borglum to critique one another’s work. Their annual exhibitions, which began in 1908, drew crowds to their small community, which straddles Norwalk, New Canaan, and Wilton. The group evolved into the Silvermine Guild of Artists in 1922.

When Schmitt exhibited etchings in the 1910 exhibition, a reviewer wished he had also shown his still-life paintings. He lived in Europe in the 1930s and returned to Silvermine in 1939, where he remained until his death at 100 years. He designed many of his picture frames, including this one.

c. 1914

Oil on canvas, 20 x 20”

Signed lower left

J. Alden Weir (1852-1919)

Portrait of Robert Weir

Weir painted this study of his artist father, Robert Walter Weir (1803-1889), just after returning from study in France. The large version was shown at the National Academy of Design in 1878, but the study was also on view that year at the new Society of American Artists, which actually wanted works without traditional “finish.” Here the sitter looks directly at us, not into distance as in the large version. A decade later Weir brought a similar immediacy to the Impressionist landscapes he painted in Connecticut.

1878

Oil on wood, 10 1/4 x 7 7/8”

Unsigned

Childe Hassam (1859-1935)

News Depot, Cos Cob

Hassam, who was in Cos Cob periodically for 20 years, memorialized a store visited daily by the artists who boarded at the Holley House. Because they feared their favorite village would grow crowded, the artists shunned publicity. Residents were grateful for that and for the increased income that the artists brought them. In time, artists and local people mingled comfortably, if not always enthusiastically, in Connecticut towns that had an art colony.

1912

Oil on cigar box lid, 5 1/4 x 8 3/4”

Signed and dated on reverse

Mystic, Silvermine & Beyond

Art colonies grew because artists heard about them from friends or were impressed by paintings they saw. By the late 1890s Charles Davis had attracted a number of artists to Mystic, Connecticut: “The pallet [sic] and easel have become familiar sights along the river, and the village streets, and among the hills.”

Artists who settled there include several who had studied together at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Henry Ward Ranger moved from Old Lyme to Noank in 1904. This small fishing and shipbuilding village near Mystic had been attracting artist visitors, and several would decide to live there. The Mystic Art Association, which includes Noank artists, was founded in 1913.

In Silvermine, which spans parts of Norwalk, Wilton, and New Canaan, the sculptor Solon Borglum founded yet another art colony. The artists who came to live near him in the mid-1890s met weekly in his studio to critique or “knock” one another’s work. “The Knockers” began holding exhibitions in 1908. They became the progenitors of today’s Silvermine Guild of Artists, which was founded in 1922 and even then included painters, illustrators, architects, craftspeople, musicians, and writers. Painting styles in the early days of the Guild ranged from Impressionism to Social Realism to Modernism.

Artists also gathered in Westport, Norwalk, Darien, Wilton, Essex, Kent, and other towns. Trains had helped establish the art colonies at Cos Cob, Old Lyme, and Mystic. When automobiles became common, Connecticut’s art colonies developed into much larger art associations, which grew up in cities and towns throughout the state and did not need a core of artist residents in order to thrive.

Edward H. Barnard (1855-1909)

Mystic Valley

A noted Boston artist, Barnard began summering in Mystic, Connecticut, in 1892, almost certainly because his artist friend Charles H. Davis had just settled there. Before leaving France in 1889 for a teaching job in the Boston area, Barnard saw an exhibition of paintings by Claude Monet that transformed him from a figural painter into a landscapist. Monet’s pictures, he said, showed him how to paint outdoor light. Barnard declared the atmosphere of the Connecticut shoreline to be the best he knew for painting.

Oil on canvas, 17 1/8 x 21 1/4”

Signed lower left

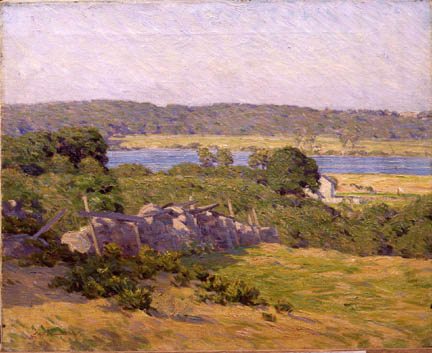

Charles H. Davis (1856-1933)

Twilight Over the Water

Painted the year he moved to Mystic, this scene shows that Davis, a Massachusetts native who had lived in France for a decade, where he painted the restrained, atmospheric country scenes that characterize French Barbizon art, was already responding to the strikingly different light and look of shoreline Connecticut.

His French works also silhouetted low-lying landscapes against the sky, but they were smoothly painted in sober tones and the sky had a soft glow. They gave no hint of the brilliant color and aggressive paint application that enliven this early Mystic painting.