Collections

In Situ: The Painted Panel

- The Museum will be closed Thursday & Friday, November 27 & 28.

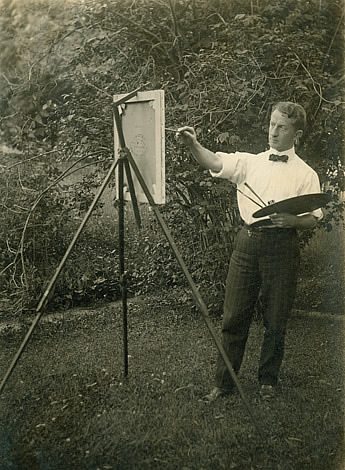

Arthur Heming (1870 – 1940)

Shooting the Rapids

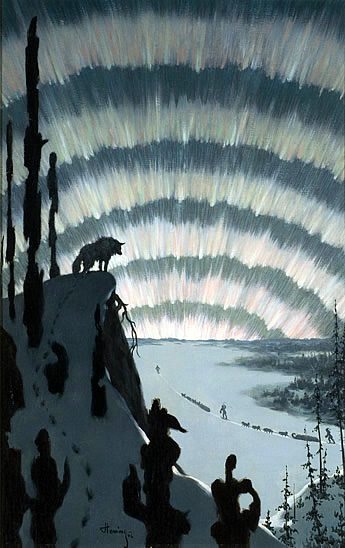

For the dining room panel that would his mark his stay in the Griswold House, Arthur Heming chose the wilderness subject matter he was best known for. This Ontario native knew firsthand what it was like to brave dangerous rapids in a fragile canoe. He had begun making trips into northern Canada when he was 16 and eventually racked up thousands of miles by canoe, raft, snowshoe, and dog team.

If the rapids in this scene look too wild for even the most skilled canoeists to run, you are probably right.

Heming was not interested in photographic representation of actual facts. He dramatized his imagery with boldly emphasized patterns and sweeping, strongly marked rhythms. In this scene the rocky foreground is large and menacing, the path of the rapids narrow, and the turbulent whitewater not without debris, so that one false move or twist of fate and canoe and canoeists are utterly destroyed. “No, you could not run rapids like that,” a fellow Canadian has written of Heming’s art, “but you could imagine that if you did it would look like that.”

You could also imagine, without ever having set foot in an Indian canoe or run rapids, that you would strain your body forward in the manner of these two figures as they try to survive in these dangerous waters.

That colors are limited to shades of black and white only adds to the drama of the scene. Heming had for years limited his palette in this very unusual way because he had been told he was colorblind. He only began to use colors when, at age 60, he realized it was not entirely true.

The first Miss Florence and the Artists of Old Lyme was published by the Lyme Historical Society in the 1971, and the second, a more fictionalized version with changed people and place names, The Lions in the Lady’s Den remains unpublished. While most Old Lyme artists wintered in New York City, Heming’s studio was in Toronto. Though largely forgotten now, even in Canada, Heming was once widely honored and exhibited, especially in England.

Heming’s experiences must have fascinated the other artists at the Griswold House, where he summered from 1902 to 1909. None had a life anything like his. Heming was essentially an illustrator, which could have diminished him in their eyes, but he had the approval of their Old Lyme associate, Frank DuMond, who had taught Heming and respected him. Furthermore, Heming had an international reputation as an illustrator of exceptional merit. He wrote as well as illustrated several books about the remote places he experienced on his travels and was called “Chronicler of the North.” Heming was a genial man, well-liked by Miss Florence and her artists, and he appreciated his experience at the Griswold House so much that he wrote two books about it.