Collections

Highlights

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

The collections of the Florence Griswold Museum span the history of American art from the 18th century to the present day with a focus on the art and culture of Connecticut.

Founded around the ca. 1817 Florence Griswold House that housed a summer artists’ colony at the turn of the 20th century, the Museum’s holdings include iconic examples of American Impressionism by artists drawn to the picturesque town of Old Lyme and its surrounding landscape. They include some of the most prominent American artists of that day, many of whom contributed a painted panel to the interior of Miss Florence Griswold’s boarding house as a mark of distinction among their peers. The house today is furnished with a selection of fine and decorative arts from the collections. In 2002, the Museum’s collections were transformed by a monumental gift of 190 paintings and sculptures from The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. This landmark donation included colonial paintings by Ralph Earl and Ammi Phillips, landscapes by Hudson River School masters Thomas Cole and Frederic E. Church, and beloved Impressionist views by Childe Hassam, Matilda Browne, Willard Metcalf, and John Henry Twachtman.

American Art in the 20th Century

The Florence Griswold Museum’s collections continue to grow with recent acquisitions highlighting modern and contemporary artists working in Connecticut. These include works by Joseph and Anni Albers, Sol LeWitt, Walker Evans, and others who transformed American art in the 20th century and continue to do so today.

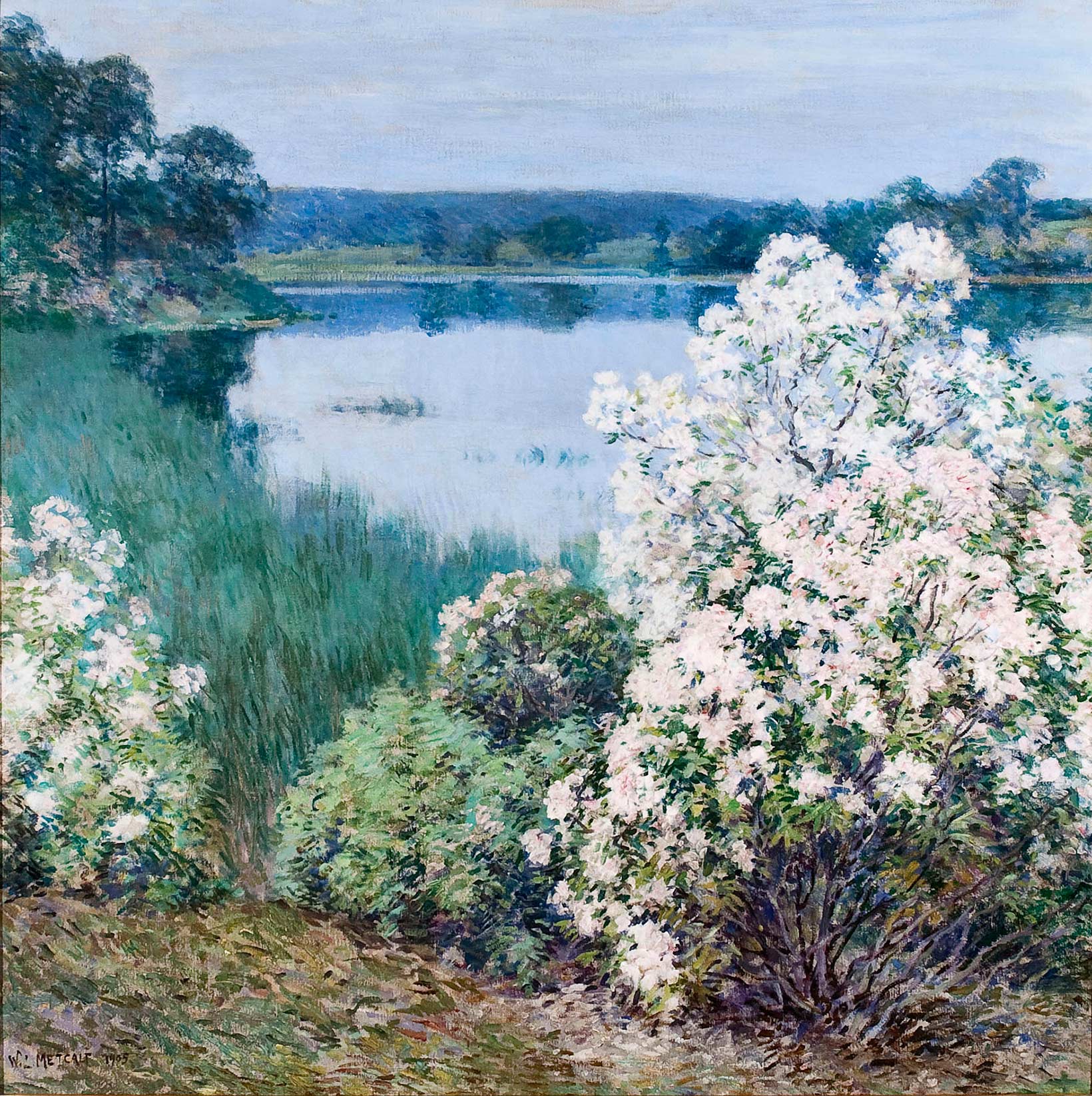

1858–1925

Willard L. Metcalf

Willard L. Metcalf, Kalmia, 1905. Oil on canvas, 34 x 34 in. Museum Purchase through The Nancy B. Krieble Acquisition Fund, with the support of Geddes and Kathy Parsons; The Dorothy Clark Archibald Acquisition Fund; Helen E. Krieble; V. J. Dowling; Max and Sally Belding; Richard and Barbara Booth; Mr. and Mrs. David W. Dangremond; Charles and Irene Hamm; William E. Phillips and Barbara Smith; Andy Baxter; Charles T. Clark; Jonathan L. Cohen; Jim and Hedy Korst; Mr. and Mrs. S. Van Vliet Lyman; Clement C. and Elizabeth Moore; Robert and Betsey Webster; Renée Wilson; Peter and Karen Cummins, and a small group of members. 2009.10

Encouraged by his friend and fellow Impressionist Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf first arrived in Old Lyme in May 1905 to spend the summer at Miss Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse. Kalmia depicts the mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) that blooms along the banks of the Lieutenant River each June. Metcalf was so pleased with Kalmia that he chose to exhibit it widely, starting in Old Lyme and continuing across America.

Critics instantly recognized the painting’s significance: “Willard Metcalf is at his best in Kalmia,” one wrote, “with its flowering bushes at the side of a stream, the delicacy of the pink and white blossoms being caught with tenderness and feeling, the result being a picture having much of the poetry of nature.” The acclaim Metcalf received for the picture encouraged other painters to take up the Kalmia motif, making it a signature subject for the Lyme Art Colony.

1869–1947

Matilda Browne

Peonies, ca. 1907

Oil on wood Original Carrig-Rohane frame 1907

Florence Griswold Museum Purchase 2013.11

This recent addition to the Museum’s collection embodies the essence of plein-air painting. Matilda Browne captures the glorious sunshine and lush color of a June day, when the peonies bloomed in profusion in Old Lyme. The painting is thought to depict the garden of Katharine Ludington, down the street from Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse. While some Impressionists may have preferred to work on a white ground, Browne nonetheless achieves brilliant sunlit effects against the brown wood of a panel.

Browne likely selected a wood panel as her support because it could stand up to the rigors of outdoor sketching, which included wind and uneven terrain. Wood panels could be propped inside a sketchbox or clamped to a folding easel, all parts of the plein-air painter’s kit. The painting retains its original frame, carved by Hermann Dudley Murphy, who signed the back. Murphy and his partners in Boston introduced handcrafted art frames to America as an antidote to commercially available frames.

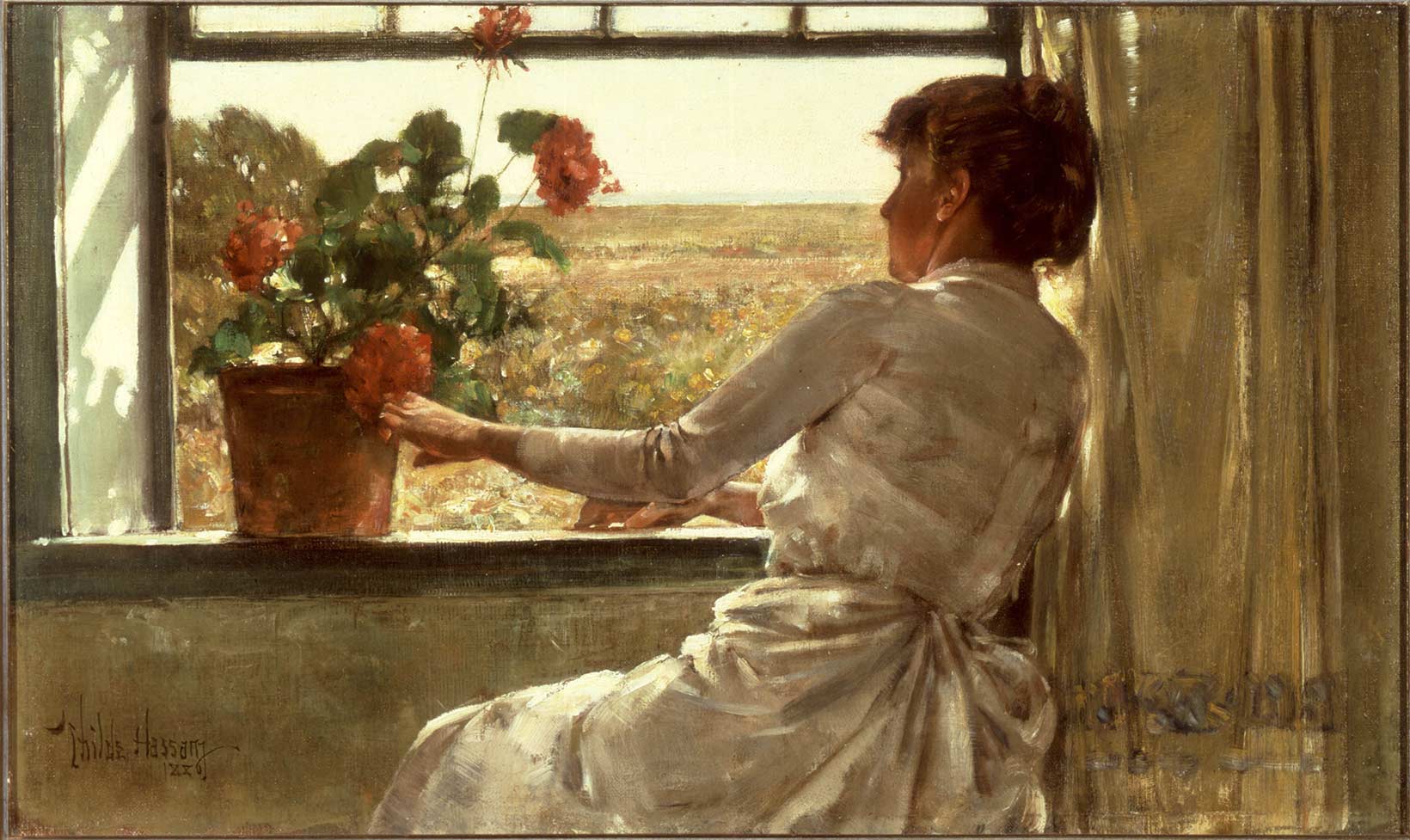

1859–1935

Frederick Childe Hassam

Summer Evening, 1886

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.71

Childe Hassam created Summer Evening the year he first visited Appledore Island in the Isles of Shoals, a resort off the coast of Maine presided over by gardener and poet Celia Laighton Thaxter. In this painting, possibly completed there, the woman angles her body away into the shadows while the potted plant leans toward the sun. Painting in Cos Cob, Old Lyme, and New York, Hassam would return many times to the theme of a woman near a window contemplating her relationship to the outside world.

The same year he completed Summer Evening, Hassam went to Paris to study. There, he absorbed the style of artists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, though he never had direct contact with any of the French Impressionists. When he returned to the United States he roamed up the east coast visiting different artists’ colonies and enclaves, spreading the Impressionist style.

1874-1965

Will Howe Foote

Summer, c. 1913

Oil on Canvas

Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert H. Krieble 1994.5

This painting depicts the artist’s wife Helen, their son Freeman, and a friend in the family’s garden in Old Lyme. The Footes moved into their new home in Old Lyme in 1909 and developed an Italianate-style garden with terraces and paths that overlooked the Lieutenant River.

Unlike the more muted tonalities of Foote’s earlier, largely figurative work, Summer shows how the artist’s palette became increasingly high key in nature. Boldly applied strokes of contrasting purples, yellows, and greens convey the intense midday light of summer in Old Lyme.

1879-1962

William Chadwick

On the Piazza, 1908

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Chadwick O’Connell 1975.7.1

Employing a lush Impressionist palette, Chadwick conveys the pastoral setting of the Griswold estate. Pink hollyhocks can be seen at the left, grapevines cover the porch, and a garden of roses, daylilies, and perennials can be seen in the distance. The varied hues of the garden suggest the multitude of flowers growing in Florence Griswold’s garden.

The positioning of the garden near the house was in keeping with early 20th century advice for augmenting the home. Depicting a young woman who exists on the threshold between the indoors and outdoors, Chadwick links the early architecture of the house with the equally “old-fashioned” garden beyond.

1858-1916

Henry Ward Ranger

Mason’s Island, 1905

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.113

With its mix of pastoral settlement and sheltering forests, Mason’s Island off the coast of Noank, Connecticut, represented Henry Ward Ranger’s ideal landscape. As one critic wrote in 1905, “Fontainebleau has nothing better to offer than what may be seen any day on Mason’s Island.” After 1903, when the influx of large numbers of art students made Old Lyme less desirable to Ranger, he moved to nearby Noank, but maintained ties with fellow artists at Old Lyme.

In Mason’s Island, his characteristic golden tones and glazes have been enlivened with touches of blue. Despite his reputation for strictly employing Old Master techniques, Ranger later adapted his palette as a response to the brighter tones of the Impressionists he encountered in Old Lyme.

1859–1935

Frederick Childe Hassam

The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1907

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.66

Already familiar with other New England art colonies, Childe Hassam found much to like in Old Lyme, including the town’s history and rugged terrain. He depicted the area’s rock ledges in both spring and fall during stays at Florence Griswold’s boarding house. Choosing a square canvas and setting a high horizon line, Hassam creates a mesmerizing, almost decorative pattern of autumn leaves, tree trunks, shadows, and boulders with flickering touches of his paintbrush. Compared to the softer, smoother surface of Hassam’s Summer Evening, The Ledges demonstrates the high-key color and active brushwork soon embraced by fellow artists in Old Lyme, shifting the colony’s orientation from Tonalism to Impressionism.

1867–1952

Louis Paul Dessar

The Wood Chopper, 1906

Oil on canvas

Gift of Fenton L.B. Brown 1983.30

In 1901 Louis Paul Dessar purchased a 600-acre estate on Becket Hill in the neighboring town of Lyme. The rural region was particularly suited to his interest in painting landscapes in the Barbizon tradition. To provide himself with models, he stocked his farm with sheep and oxen. Dessar found in the character and flintiness of the New England wood chopper a subject rich with possibility. Tonalist painters like Henry Ward Ranger and Dessar were greatly influenced by their admiration of the Old Masters.

They used glazes and varnish to imitate the golden tone of those paintings, which was often caused by old varnish layers that had darkened. Tonalists believed that their works would “ripen” and improve with time—in fact, glazes that were originally slightly brown have often become even darker over time. Paintings like The Wood Chopper led Impressionists to jokingly label Tonalists the “baked apple” or “brown gravy” school.

1865-1951

Frank Vincent DuMond

Top of the Hill, c. 1906

Oil on academy board

Florence Griswold Museum 1980.1

This work was painted across the road from DuMond’s summer home on Grassy Hill in Lyme. DuMond expressed his affection for the area in a 1907 interview in The New York Sun: “Every year I grow more deeply attached to my summer place and less inclined to leave it.

All of us who are associated with the Lyme colony I think have the same feeling, and our summer term has every season a more and more elastic limit.”

1876–1949

Edmund Greacen

The Old Garden, c. 1912

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. Edmund Greacen, Jr. 1974.1

In the spirit of the Colonial Revival, Edmund Greacen celebrates the “old-fashioned” garden, a prime example of which was to be found on the grounds of Florence Griswold’s house. Such gardens were filled, as countless books and articles put it, with the kinds of quaint perennial and biennial flowers “that grandmother grew.” Reacting against commercialism and industrialization, old-fashioned gardens set aside the showy, structured displays of annuals popular in the mid-nineteenth century in favor of informal plantings of unpretentious beauty.

As one garden writer described, “It is the charm of the old garden, as well as its form and plants, which we are seeking to recall…and this charm lies in the ancient estimate of homely, simple things at their true high worth.” In his rendition of Miss Florence’s garden, Greacen paints in a vague impressionistic style. His soft brushwork and melting colors are key to establishing the dreamy, nostalgic mood necessary to appreciate the old garden.

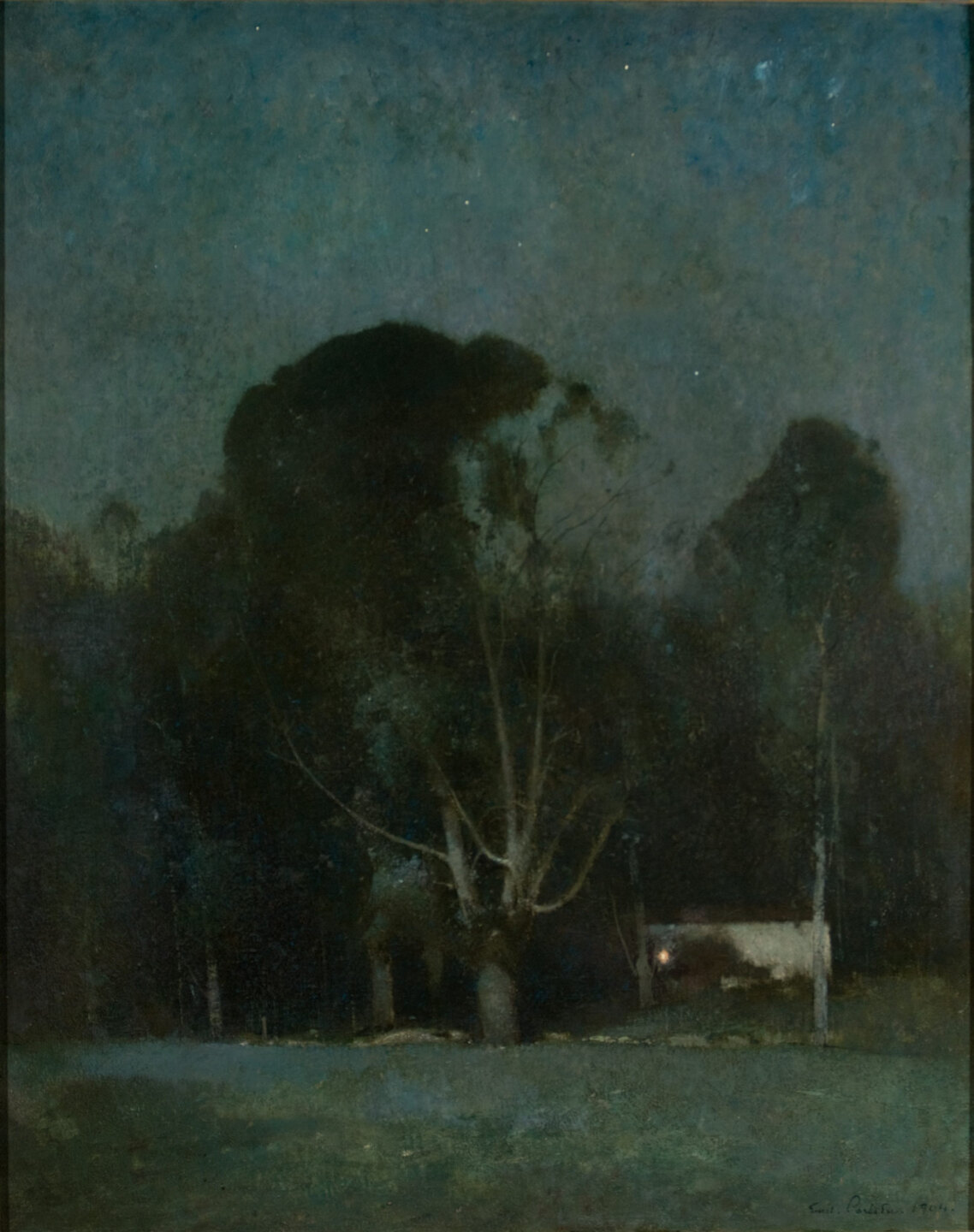

1853–1932

Emil Carlsen

Night, Old Windham, 1904

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.25

The Danish-born Emil Carlsen trained as an architect before emigrating to the United States in 1872. Over the next two decades, he studied and taught art in Chicago, Paris, San Francisco, and New York, and built a reputation as a still-life painter. In 1896, Carlsen began summering in Connecticut, where he took up the subject of landscape. At first, he stayed at artist J. Alden Weir’s home in Windham Center, even residing with his family in a cottage on Weir’s property.

This painting, completed in 1904, probably depicts that spot. The following year, Carlsen bought his own home in the northwest Connecticut town of Falls Village. The limited tonal range and carefully constructed surface of Night, Old Windham recall the work of John H. Twachtman, the influential Impressionist and teacher whose paintings Carlsen admired. Carlsen’s intimate response to nature creates a hushed, dreamlike mood that is the hallmark of his landscapes.

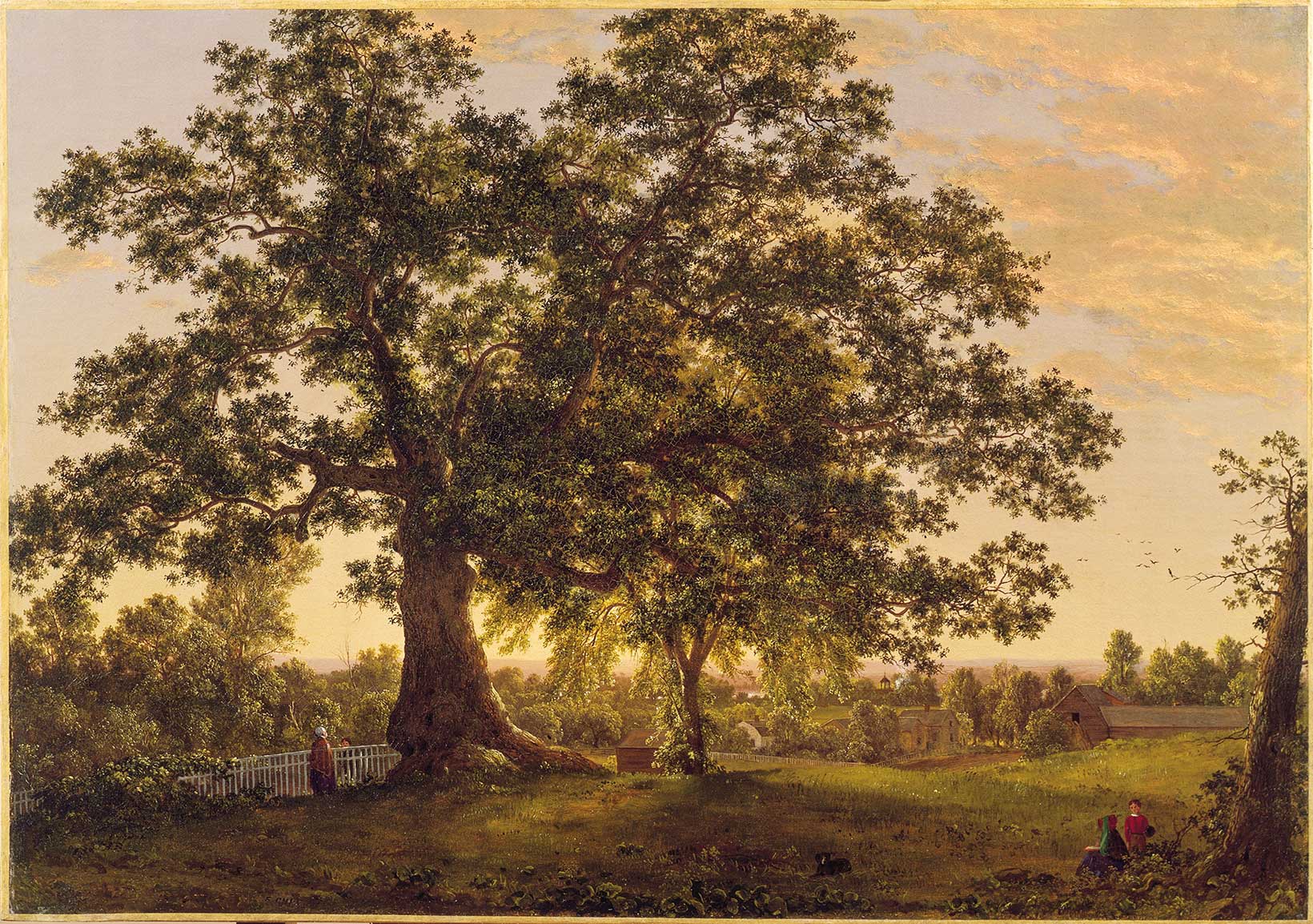

1826–1900

Frederic E. Church

The Charter Oak at Hartford, c. 1846

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.29

While still a student of Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole, Frederic Church returned to his native Hartford to create this homage to Connecticut’s Charter Oak. In 1687, Connecticut had stood alone in New England in defying James II’s orders to relinquish the 1662 charter that had given the colony a degree of self-government. According to legend, candles in the room where colonists confronted the King’s armed forces sputtered out, and in the darkness the charter was hidden in an ancient oak down the street.

The tree came to represent America’s commitment to freedom in the face of tyranny. Church silhouetted the Charter Oak against the sky and chose not to include a nearby house in order to reinforce the notion of the tree as a timeless symbol of liberty. This painting is one of several that Church completed during the 1840s, each linking the theme of freedom to places and events from Connecticut’s past—a nationalistic tone he would continue to celebrate in his later Hudson River School landscapes.

1801–1848

Thomas Cole

Study for A Wild Scene, 1831

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.34

Through the support of his Connecticut patron Daniel Wadsworth, English-born Thomas Cole painted landscapes that captured America’s natural beauty. This canvas, executed in Italy, is an early study for the allegorical Course of Empire series of five paintings depicting the rise and fall of a great civilization. Although the stormy landscape appears untamed, the presence of small figures to the right of center suggests that the process of settlement is beginning.

Cole lamented that America’s quest for progress came at the cost of its wilderness and inspired other artists of the Hudson River School to celebrate this unique national heritage. Seventy-five years later, the plein-air painters of the Lyme Art Colony would record the results of this gradual domestication—the pastoral landscape of coastal Connecticut.

1751–1801

Ralph Earl

Mrs. Guy Richards of New London, 1793

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.52

Ralph Earl completed over one hundred portraits of Connecticut sitters, including six members of the family of Thomas Shaw of New London. He depicted Elizabeth Harris Richards (1727–1793), Shaw’s sister-in-law and the wife of a prominent dry goods merchant, the year that she died. Although training in England had taught the American-born Earl to stress elegance and refinement in his portraits, his American patron called instead for an emphasis on the elderly woman’s forceful character.

Richards holds a copy of Philip Doddridge’s Family Expositor: or, A Paraphrase and Version of the New Testament, a popular guide for family worship. Eyeglasses in hand, she appears ready to instruct the viewer, at whom she gazes intently. Behind her, a window provides a glimpse of her husband’s wharf in on Winthrop’s Cove, an inlet of the Thames River.

1791–1834

Harlan Page

Portrait of a Man, ca. 1815

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.102

One of the most extraordinary early American portraits, this likeness of a flame-haired man depicts someone full of religious fervor—probably the artist himself. Harlan Page was “born again” in 1814 during the religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening, and afterwards devoted himself to evangelism.

He claimed to have converted more than one hundred people “through my own direct and personal instrumentality.” Page’s biographer mentions that he drew when he was too ill to do much else, and that in 1825 he was drawing and engraving in Norwich, Connecticut. Only one other portrait and a tavern sign by his hand have survived.

1852–1896

Theodore Robinson

Autumn Sunlight, 1888

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.114

While working in the orbit of Claude Monet in Giverny, France, where he completed this painting, the American artist Theodore Robinson struggled to translate his impressions of nature to canvas without resorting to stylistic formulas. The vague treatment of the woman’s face and vegetation with a flurry of brushwork imparts a sense of immediacy and blurred motion that may derive from Robinson’s reliance on photographs as compositional aids.

His subtle handling of space and the woman’s face are easier to appreciate since the recent removal of a varnish layer that was applied to the painting after it left the artist’s hands. Robinson’s sensitivity to visual effects echoes that of fellow Impressionist John Henry Twachtman. Robinson spent time with Twachtman in Greenwich during periodic visits to America in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

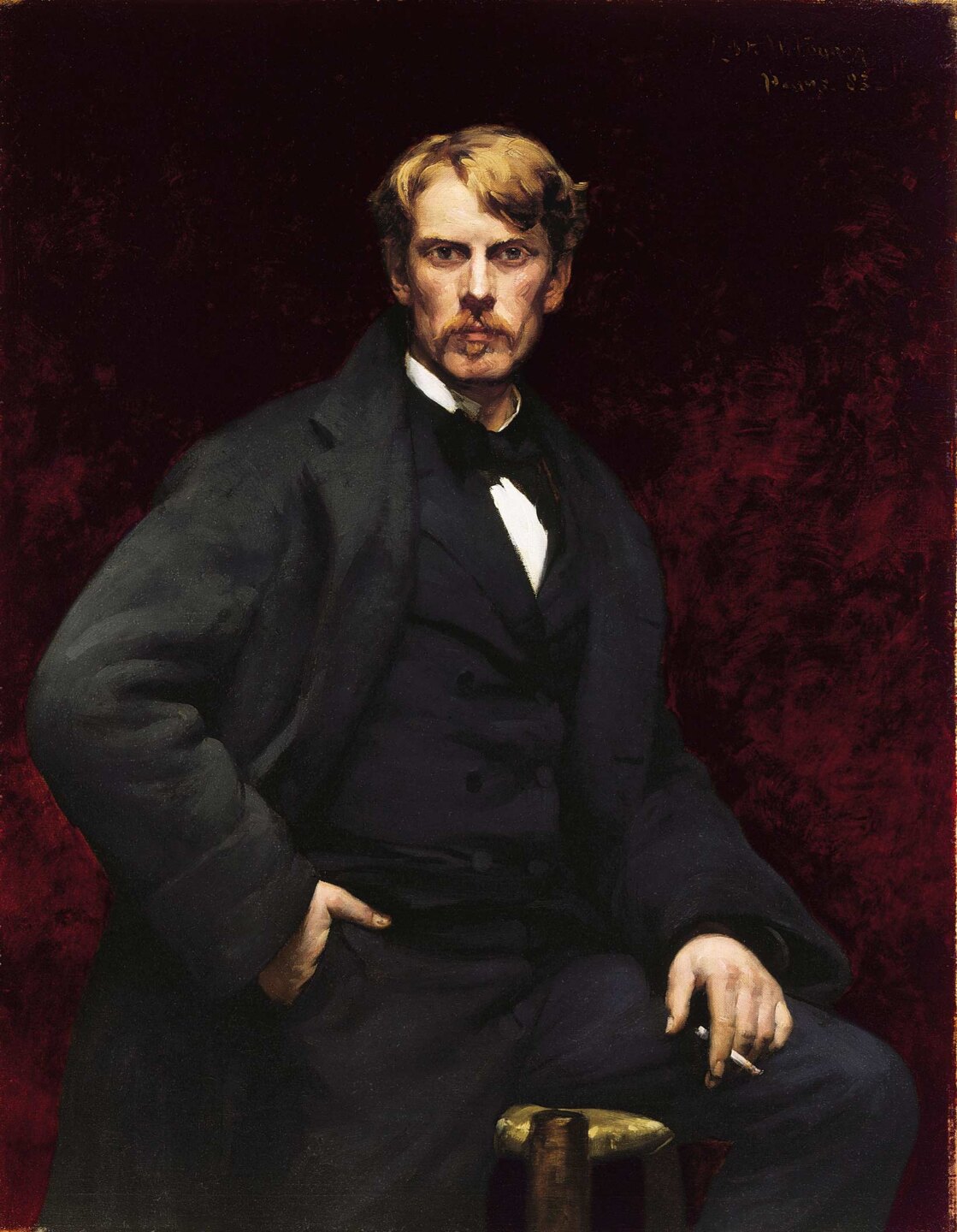

1858–1933

Robert Vonnoh

Portrait of John Severinus Conway, 1883

Oil on canvas

Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.149

Later a member of the Lyme Art Colony, Robert Vonnoh won acclaim at the Paris Salon for this depiction of the debonair, cigarette-wielding John Severinus Conway (1852–1925), an American sculptor who studied alongside him at the Académie Julian. Painted the year that Vonnoh returned to America to teach and Conway moved to Rome, the portrait marks the culmination of the men’s experiences in French art academies; Vonnoh demonstrates the fluid brushwork and forceful portrayal of character he mastered by completing the full-length figure study required of pupils each week.

Yet his depiction of Conway hints at the challenges of life in the intensely competitive Académie Julian. Conway perches on a rush-seated stool like those awarded to students based on their weekly class ranking. Arrayed concentrically, higher stools, like Conway’s, stood further from desirable spots near the nude model. Vonnoh’s use of harsh lighting, like that from the atelier’s skylights, chisels the sculptor’s features, making him appear gaunt. Conway never achieved Vonnoh’s success and letters to American friends from this time attest to the melancholy lurking in this portrait.

1853–1902

John Henry Twachtman

Gloucester, ca. 1898–1902

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company 2002.1.144

John Henry Twachtman favored the diffused light that pervades this sun-washed landscape and applied his pigments thinly to suggest the summertime brilliance. He had first gathered a community of artists around him in Greenwich, where he settled in the late 1880s.

There, he offered lessons in plein air painting in the summers and taught in the winter in New York at the Art Students League. Between 1900 and 1902, Twachtman held summer classes in Gloucester, where he completed this painting.

1871-1964

Harry Leslie Hoffman

A Mood of Spring, ca. 1913

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. John Hoffman and Family 2003.8

A Mood of Spring dates from one of the most successful periods in Harry Hoffman’s career. The work earned him a Gold Medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915. Hoffman trained with Frank Vincent DuMond, who ran the Lyme Summer School of Art, as well as teaching at the Art Students League in New York. After his student days in Lyme, Hoffman departed for Europe but eventually returned to become a full-fledged member of the Lyme Art Colony.

The home pictured is that of the Harding Family who lived on Sill Lane in Old Lyme quite near the Hoffmans’ home “Chuluota,” a Native America word for “beautiful view.” Like his friend Henry C. White, Hoffman explicitly seeks to convey the mood of the landscape here. “I don’t want to be a stylist,” Hoffman wrote, “I want to paint things as they seem to me. I want to record my own impressions and not be bound by style.”

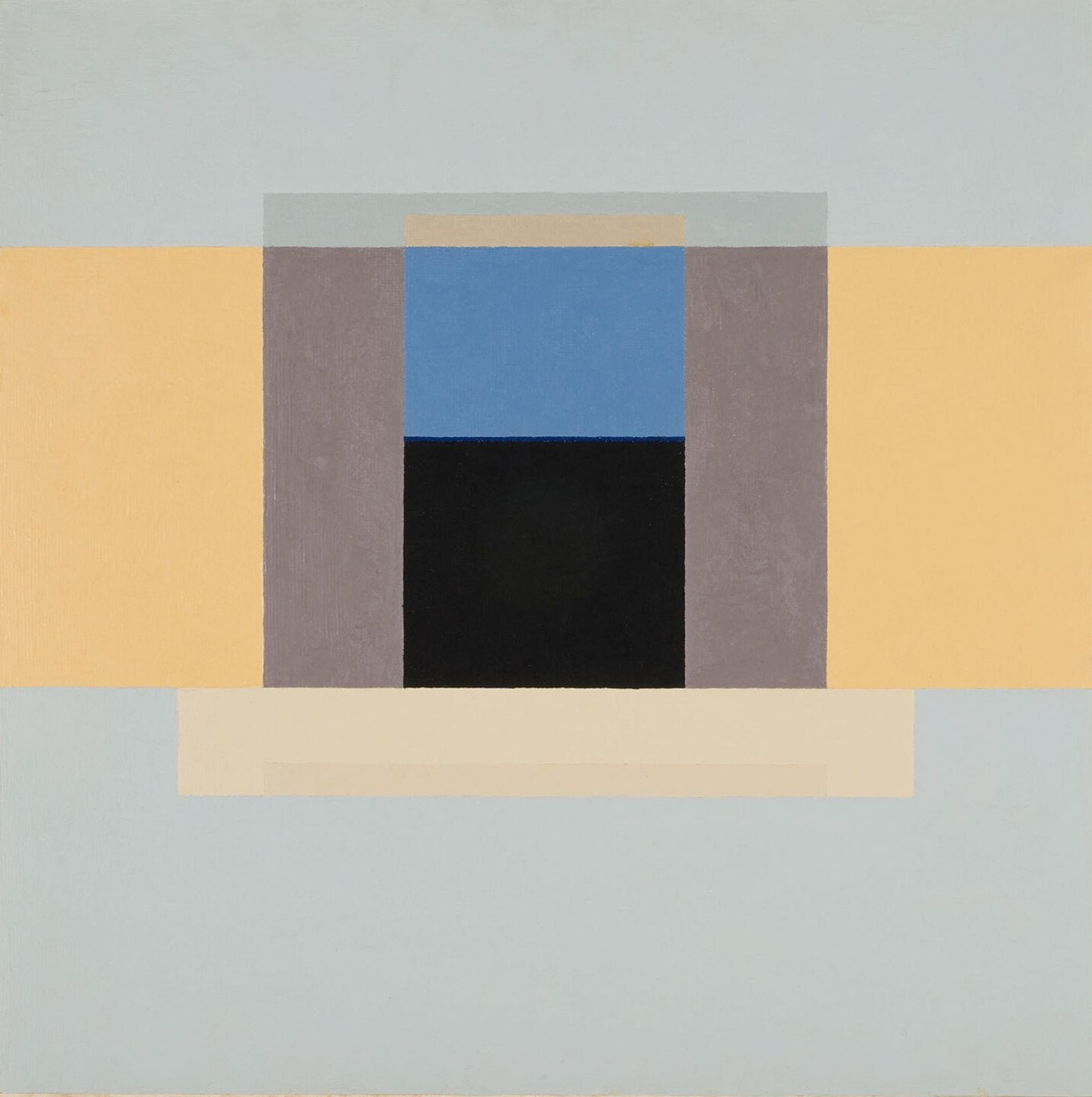

1921–1992

Sewell Sillman

Water Gate, 1960

Oil on masonite

Gift of the Sewell Sillman Foundation 2009.11.1

Sewell Sillman’s painting Water Gate is part of a series that abstractly represent doors, portals, and gates. The combination of colors, however, is the true subject here. As a student of Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, and his teaching assistant at Yale University, Sillman developed interests in color theory and design similar to those of the German Modernist.

Albers created simple geometric compositions, like his well-known “Homage to the Square” or “Variant,” designed to allow for maximum experimentation in color. The overall composition remained the same from work to work, but the color arrangements varied, demonstrating the interaction of different hues. Sillman also utilized a relatively simple geometric structure in his portal paintings, allowing his use of color to take precedence.

1872–1955

Bessie Potter Vonnoh

Jessie Wilson, 1912–13

Bronze

Florence Griswold Museum 1977.4.2

Best known for her sculptures of mothers and children, Bessie Potter Vonnoh befriended the family of future president Woodrow Wilson in Old Lyme in 1905, when Woodrow’s wife Ellen Axson first visited to pursue her studies as an artist. Jessie posed for Vonnoh as early as 1909, resulting in a work (unlocated) that Ellen Axson Wilson described as having “a sort of large nobility about it in spite of its small size.” “Of course it is too small to be a real portrait,” Ellen explained to a friend, “but it suggests her, and the lines of her head, neck and shoulders are perfect”—an evaluation that could easily apply to the work seen here.

This statuette dates from 1912, when Jessie posed for Vonnoh during visits to New York for meetings related to her settlement house work. Ellen found the piece “adorable.” Proud of the result, Vonnoh included Jessie Wilson in several exhibitions, including one Ellen arranged at the White House. According to tradition, Vonnoh gave the cast on view here to Florence Griswold, who attended Jessie’s wedding at the White House in November 1913. Following the completion of the bronze Jessie Wilson, Bessie Potter Vonnoh began a marble bust of Jessie in the summer of 1913, the same period in which her husband Robert Vonnoh executed a portrait of Mrs. Wilson and her daughters.