Fox Chase

Painting Tools

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

Scattered along the image of The Fox Chase are the tools of the artists who stayed with Miss Florence. Easels, canvases, painting umbrellas, folding stools, paint boxes, palettes, and brushes are the trappings of the artist intent on working en plein air, or in the open air.

Many of these tools have been around for centuries and have been used by artists in their studios whereas others, like the squeezable paint tube and collapsible easel, were relatively new, either invented or redesigned for this new outdoor purpose.

Artist Palette

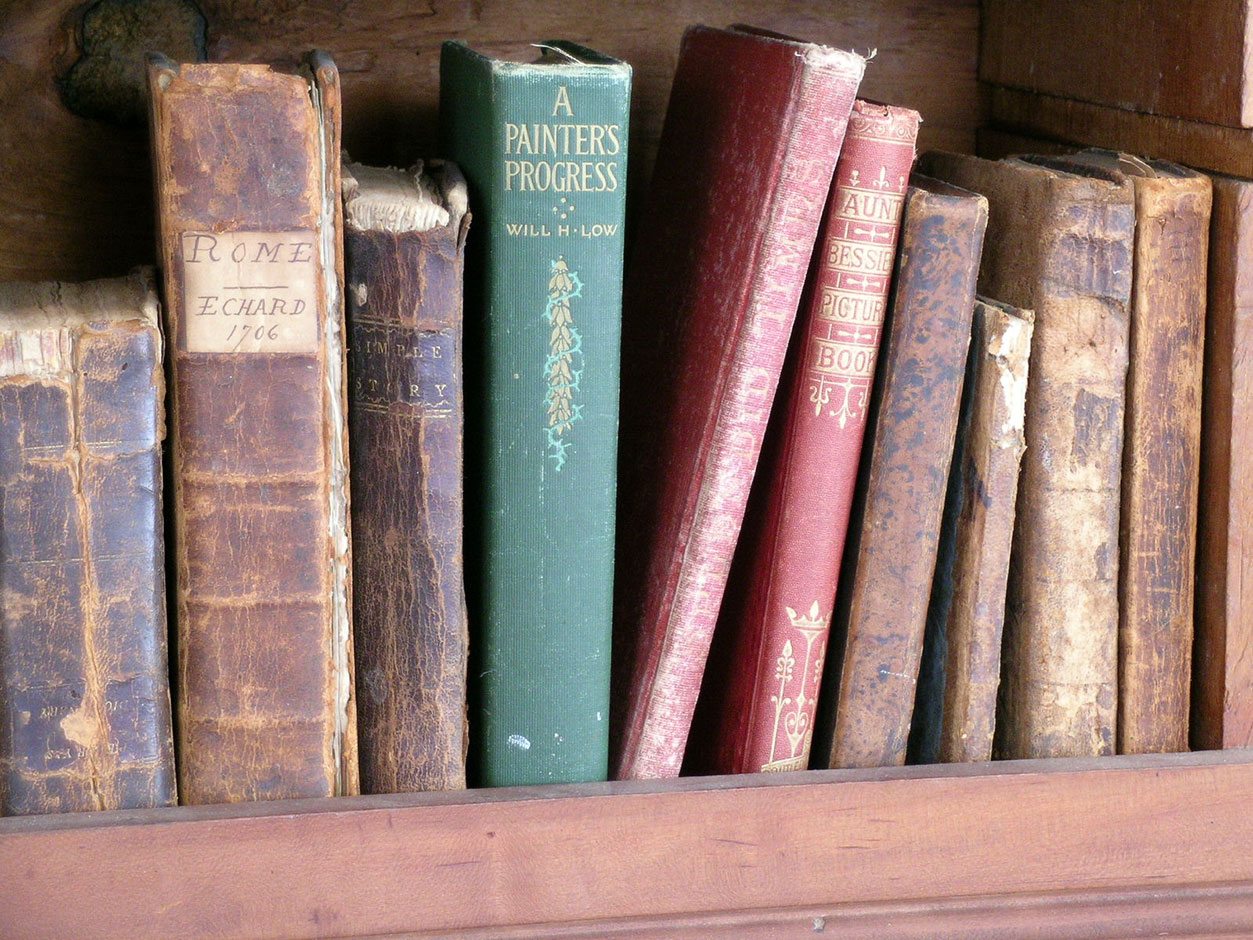

Although art is an individual expression, the tools and techniques of the artists tend to be somewhat consistent. The history of art is both a history of ideas and images as well as of the materials available to the artist (from cave walls to the latest digital media). The selection of artists’ tools below is based on the most common of materials used by the Lyme Art Colony artists as well as those that are depicted in The Fox Chase.

Paints

The Old Lyme artists used oil paints for the most part.

Oil paints are slow drying paints which are made by combining small particles of pigment (the color) with oil (the binder). Paints are made by grinding down their pigment source mineral into a powder before mixing it with the oil. Both linseed and poppy oils were popular. Linseed oil was prone to yellow over time, but poppy oil offered a smooth and even paint that was slow drying. This would be useful for artists wanting to rework sections of their painting days or even weeks later. For a thinner consistency, painters could add more oil or even a varnish to the paint.

This labor-intensive process of preparing the paint was most likely performed in the studio close to where the artist painted. However, with the increased interest in painting en plein air, or in the open air, the painters required a convenient way to transport their paints. Early on, artists had used pig bladders to hold their paint, sealing the ends with thread and puncturing the skin with an ivory tack when they wanted to squeeze out paint. The tack would then be used to plug the hole. The bladders were not air tight, however, and would quickly dry up.

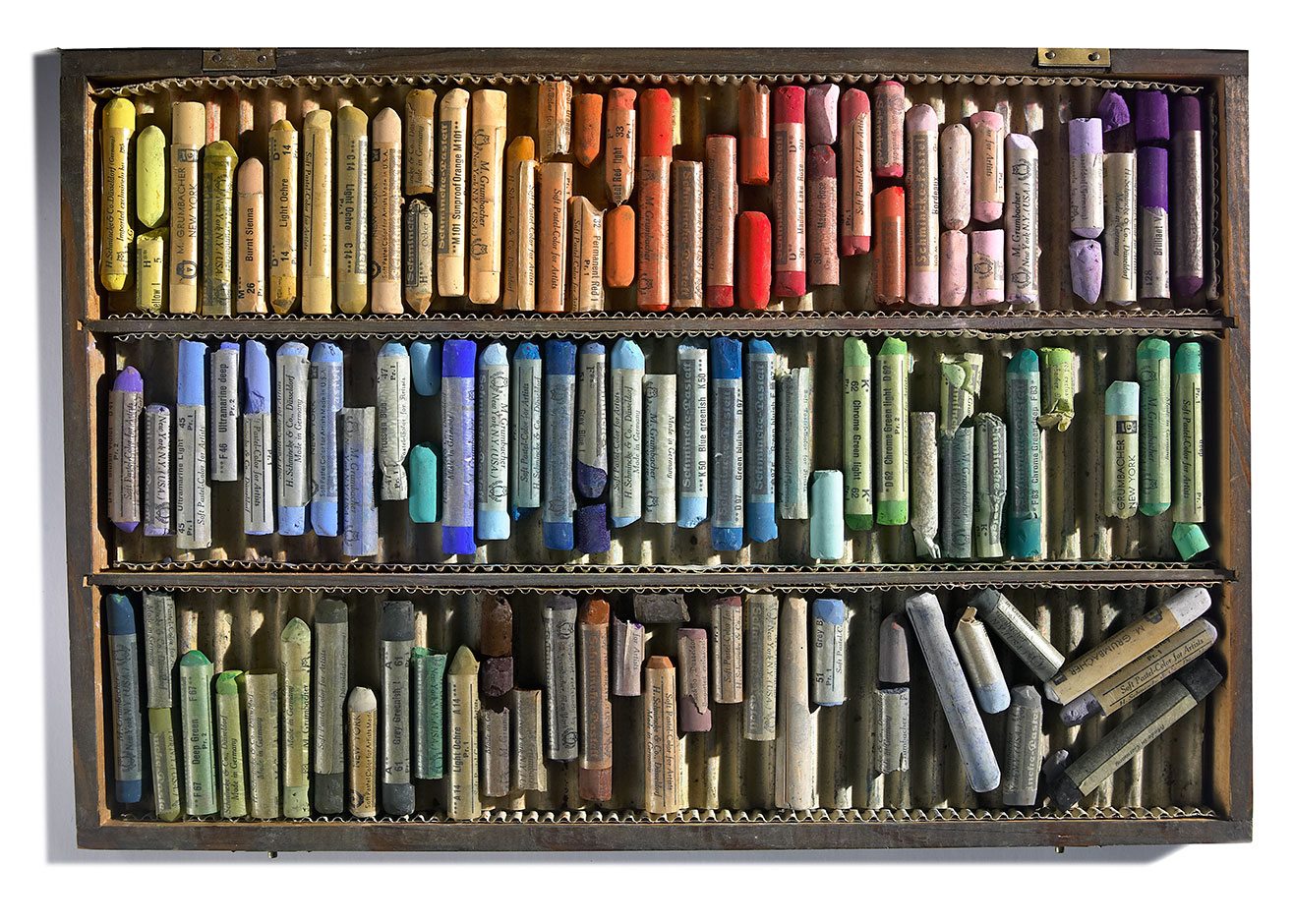

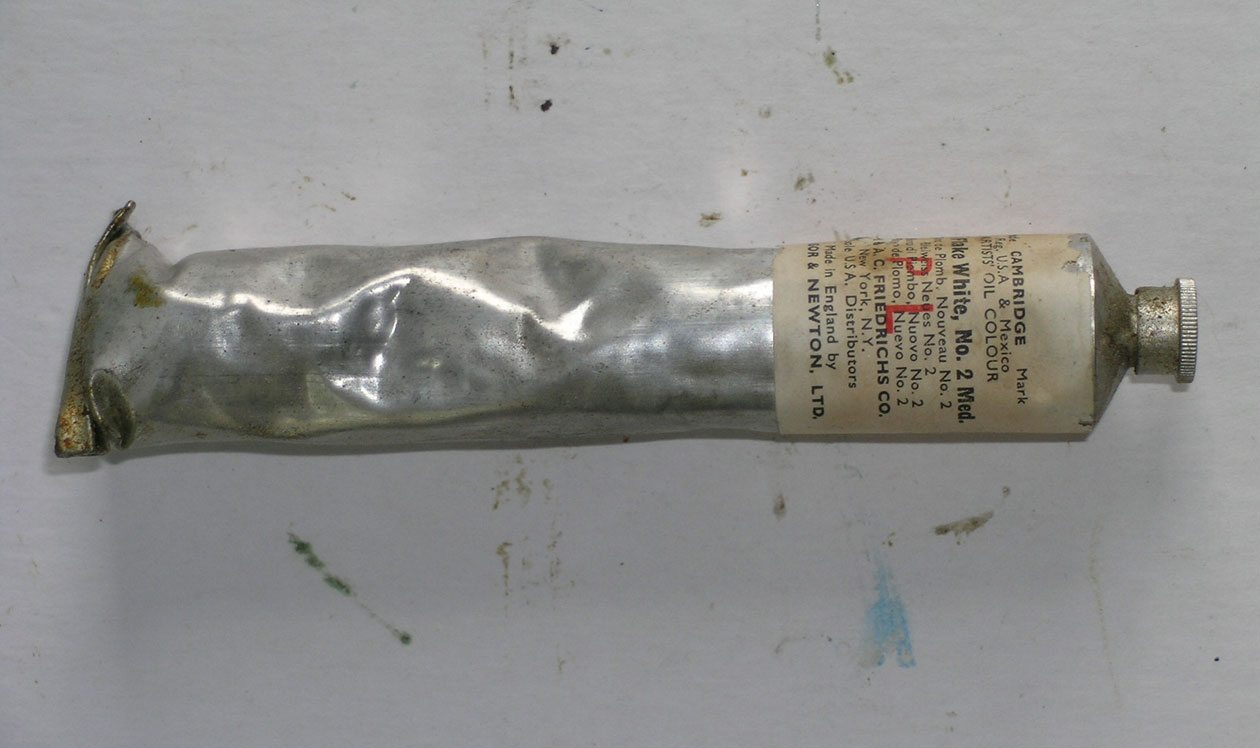

Selection of historic paint tubes from the Chadwick Studio

In the 1840s, two forms of tin tubes emerged as a solution. One worked like a syringe and the other collapsed like a tube of toothpaste. The collapsible tube became an instant hit. Artists could buy empty tubes and fill them with their paint. They would crimp the bottom closed and use the screw cap end for dispensing the paint with a gentle squeeze. The tubes were airtight, light, and unbreakable—perfect for working outdoors.

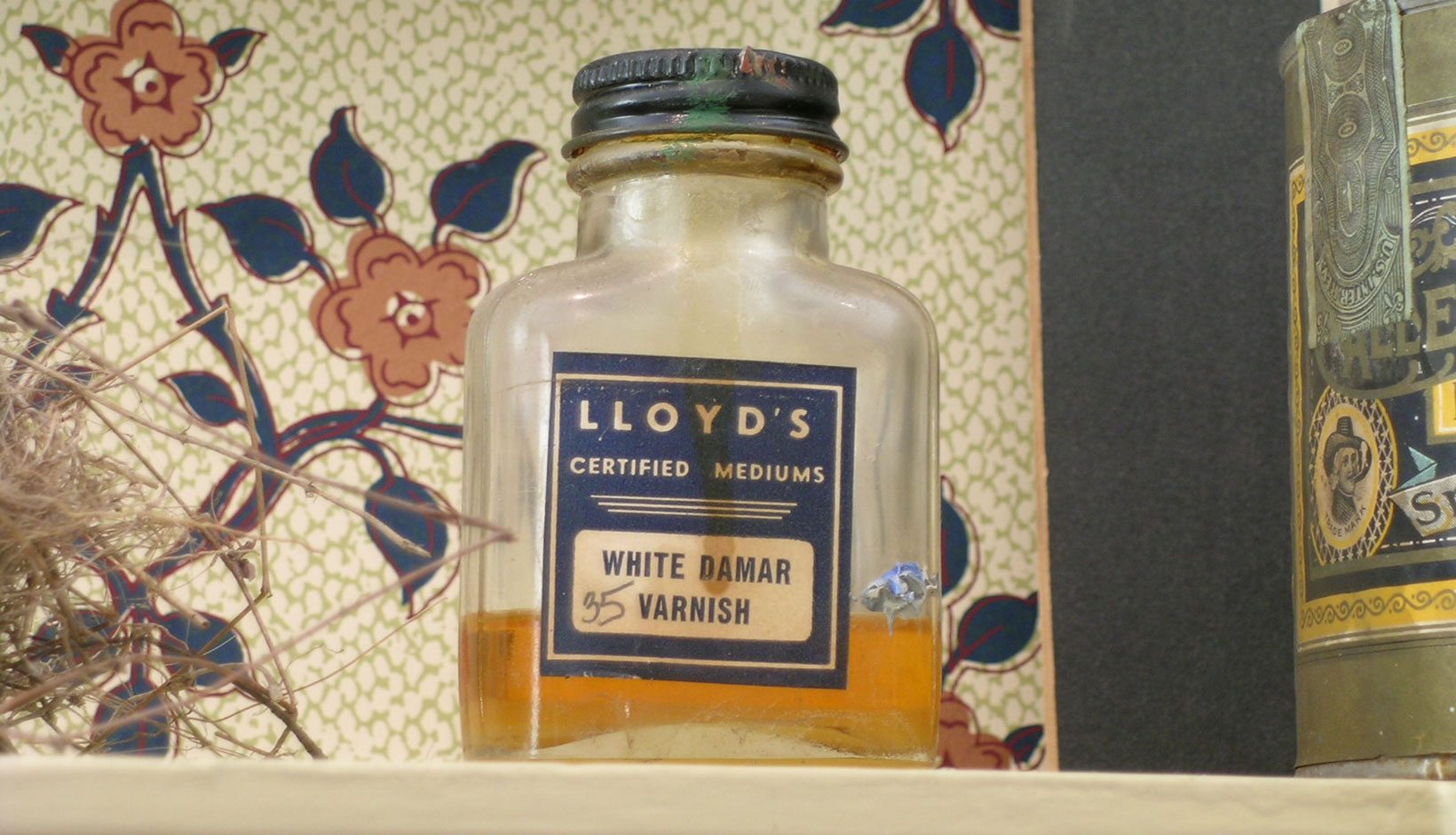

Historic bottle of varnish on the mantel of the Art Colony Bedroom in the Griswold House

By the 1870s, commercial paints were being sold in stores by color merchants. The high cost of certain minerals caused manufacturers to find synthetic sources for certain pigments and through experimentation many new colors became available. Likewise, some artists desired a thicker paint that would allow them to create dramatic brushstrokes on the canvas. Manufacturers would mix inert materials into the paint to achieve a more buttery consistency. Indeed, the Impressionists were at the forefront of painting technology and had the most modern materials, paint colors, and paint textures available than ever before in history.

Brushes

Paint brushes have three main parts: the handle, the ferrule and the bristles.

The handles are most often made of wood and come in a variety of colors. The handles of oil brushes tend to be longer to accommodate the painter who is standing at the easel. The length allows the artist to stand back from the surface while working. Likewise, the long handles make it easier for the artist to hold a bundle of brushes along with his palette in his or her non-painting hand.

The quality and nature of the brush is determined by the bristles. Most often made from animal tails or skin, individual bristles can be pointy, blunt, or split into two or more ends (these are called flagged). Pointy hairs come from sable tail hair, weasel tail hair, fitch tail hair, mongoose hair, and badger hair. Blunt hairs come from sabeline (imitation sable), ox hair, or synthetic nylon fibers. Most flagged hair comes from hogs in China. Once gathered, the bristles are bundled, tied, and glued into the ferrule, which is the metal joint that holds the bristles in place and connects them to the handle. Brushes are made pointy, flat, or angled by the shape of the ferrule opening and the trim of the bristles. Each brush shape will make a distinctive brushstroke in the paint.

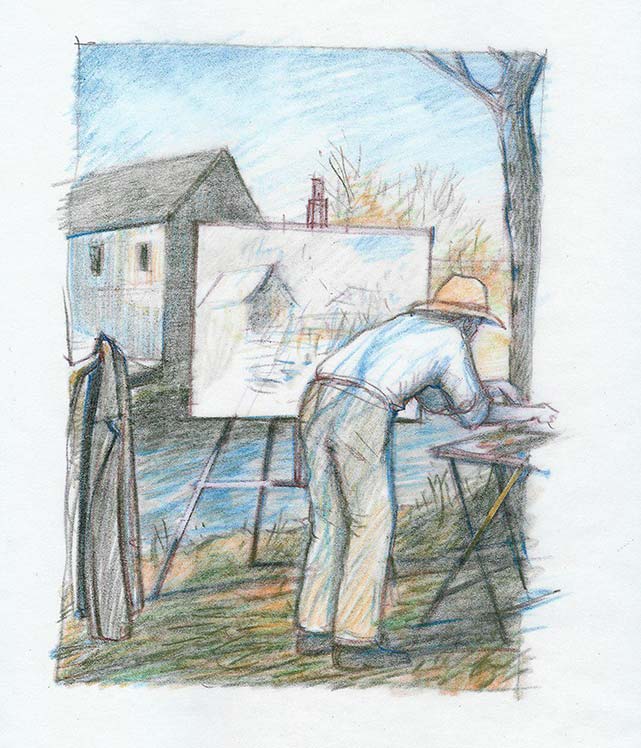

Palette

A palette is a thin, flat piece of wood that artists use to hold and mix their paints while working.

Often ovoid in shape, the palettes have a thumb hole that allows a painter to hold it securely with one hand while painting with the other.

The indention in the side of the palette allows for brushes held in the hand below to be fanned out and not touch each other. This allows an artist to have several brushes (loaded with different colors) to be in use at the same time. Rectangular palettes that can slide into grooves and held in place within a paint box are also popular. Because oil paint dries so slowly, an artist might choose to leave the thick globs of paint on a palette for weeks or even months. Palettes can be cleaned by scraping the paint off with a palette knife. After years of use, the palettes take on a colorful patina.

Detail of Miss Florence’s Artist Tree in the Krieble Gallery, 2004 Palette features a still life of artist materials (including a palette) by Michael J. Peery Photograph by Jody Dole.

On occasion, painters have painted pictures directly on their used palette. The Museum used this idea to create Miss Florence’s Artist Tree, a 12-foot tree decorated with painted palettes by nearly 75 contemporary artists, which is on display during the holiday season each year. The artists are given a new unused palette, which they donate back to the Museum after they’ve completed their painting.

Easel

Easels are used to hold the work of art in place.

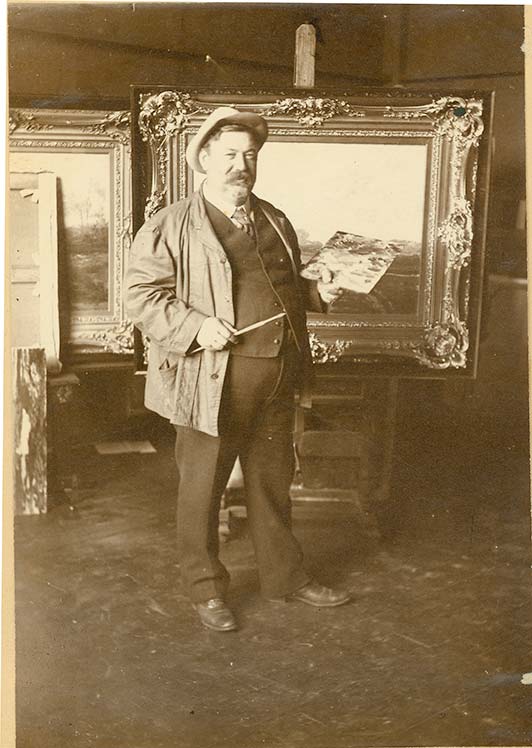

Artists often have large-scale easels in their studio that are capable of holding large canvases or panels. Easels are infinitely adjustable, with sliding parts that can be changed for each painting. However, the large studio easels are not convenient for painting outdoors because of their bulky size.

Landscape easels were invented to accommodate the growing numbers of artists wanting to work en plein air. Not only are these easels smaller when fully assembled, but they fold up to make them easy to transport. Beginning in France, manufacturers began offering outdoor painting kits that combined a paint box with a portable easel. These contained most of the supplies needed for a day of painting, and the legs could be adjusted so that the canvas could be level even on uneven terrain. One popular version is named the Jullian easel, designed by Roger Jullian, a French prisoner of war during World War II, who devoted himself to designing and later manufacturing the perfect sketch box easel.

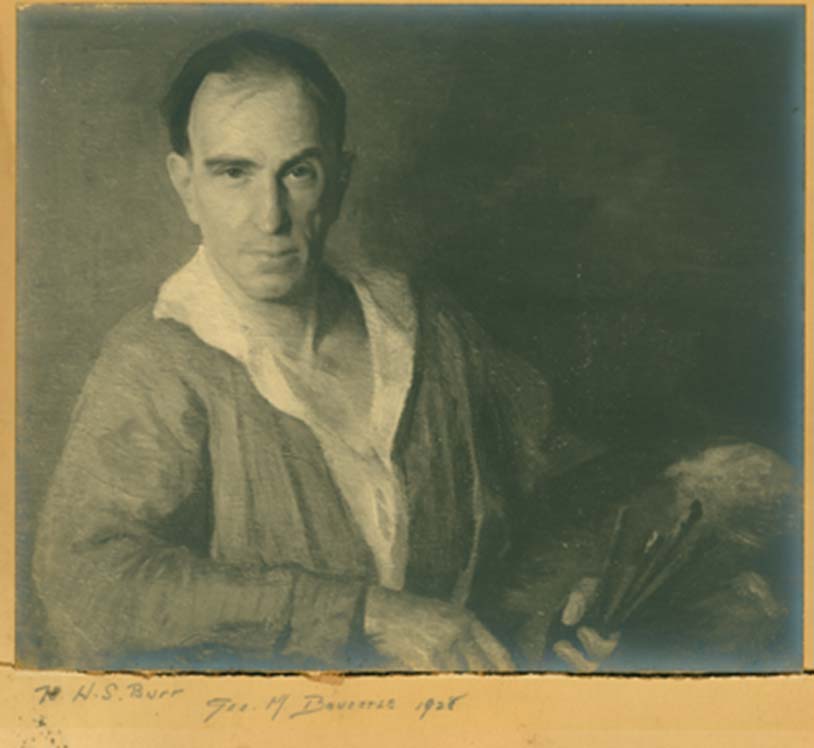

Wilson Irvine painting en plein air with portable easel

Canvas/Wood Panel

Although the Lyme Art Colony is famous for the painted panels the artists created for the boardinghouse dining room, they also worked on canvas.

Canvas begins as a woven fabric most commonly made out of cotton, linen, or burlap (linen canvas has proven to last longer than the others making it a common choice).

Detail of nailed canvas

The canvas is cut from the bolt of fabric and stretched taut over a wooden frame and stapled or nailed in place. The surface needs to be sized (or sealed), so that the fibers of the cloth won’t absorb the moisture in the paint, and then primed with a base coat to provide a ground to paint upon. Grounds are often white but can be tinted any color. Henry Ward Ranger would start with a white ground but add a transparent yellow glaze in order to begin with a color that is “most suggestive of sunlight.”

Varnish, Oils, & Solvents

After an oil painting is thoroughly dry the surface can be covered with a layer of varnish.

Varnish gives the painting a protective layer as well as restores the wet richness to the colors (most paints tend to dull or turn matt as they dry). Traditional varnishes are made from natural tree resins such as dammar or mastic (there is a bottle labeled “MASTIC” inThe Fox Chase). The resins are mixed with a solvent such as turpentine and applied to the painting.

When the solvents evaporate, a thin layer of glossy resin remains on top. Natural resins have a slight yellow appearance, which certain schools of art appreciate as it adds to the tone and makes the paintings look somewhat aged. Today, crystal clear varnishes are available. These are made from acrylic resins, which act like a plastic.

Henry Ward Ranger (1858-1916) Autumn Woodlands, 1902

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mr. Ezekial Liverant

The Impressionists on the other hand did not want that final layer of gloss that might yellow with time. Instead, it was believed that they wanted their canvases to look modern, fresh, and new—the antithesis to the Old Masters. Willard Metcalf printed warnings on the reverse of some of his canvases. He begins somewhat agitated on a painting from 1917-18 with “DO NOT VARNISH W L M” but several years and several canvases later rachets up to “NOTICE !! UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES should VARNISH or other mediums be applied to this canvas—as they will change certain ‘values’—and thereby ruin it. / W.L.M.”

Willard Metcalf (1858-1925) Dogwood Blossoms, 1906

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

More recently, however, art conservators Lance Mayer and Gay Myers have been able to study

the actual layers of pigment and varnish in both French and American paintings to discover that most artists either varnished or didn’t varnish on a case by case basis. How they wanted their final product to look determined how they treated the finished painting. Although many American Impressionist paintings hang in museums unvarnished, there are many with glossy, dazzling surfaces. Indeed, all of the panels in the Griswold dining room were varnished at regular intervals by the artists themselves, including those along the top which were painted first by artists affiliated with the Tonalists, as well as those along the bottom painted by Impressionists. Childe Hassam, who was the leading proponent of Impressionism in America wrote to his dealer about his famous flag paintings: “I will not let them go anywhere until I have varnished them all this fall or early winter.” During the mid 1980s, the art conservators Lance Mayer and Gay Myers reviewed each of the panels in the dining room to determine their condition. Their analysis provides insight into both the working methods of the artists and the changes the panels have undergone over time.

According to the examination report for the Woodhall Adams panel: “The support is a 1.3 cm (1/2”) thick piece of softwood, which has been coated with a thin paint and resin layer on the reverse. On the front, the panel has been coated with a dark mahogany stain, followed by layers of an oil-type paint, freely applied with much low impasto. There is a thin natural resin varnish coating. Some areas, especially in the foreground, which look at first like abrasion, actually appear to be the result of dark glazes which are applied very thinly and allow textures beneath to party show through. The varnish has discolored to a dark yellow color, and has attracted dark grime particles. Removing the discolored varnish and grime will make the painting dramatically brighter.” The panels were each treated in the manner suggested by the art conservators.

Portable Studio

Several of the Old Lyme artists actually bridged the gap between painting in the studio and painting en plein air.

They used portable painting studios, small compartments affixed to a rickshaw-like vehicle that they could pull into the fields to keep warm on winter sketching trips – not unlike Claude Monet who painted on the River Seine in his studio boat.