Fox Chase

School of Lyme

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

The artist Henry Rankin Poore begins his famous frieze at the far right by identifying the colony as the “School of Lyme” and flanking the words with a bottle of “MASTIC” on one side and a bottle of “RYE” on the other.

A misnomer at best, the term “school” does not refer to a teaching institution, since most of the affiliated artists were trained professionals by the time they came to Old Lyme, but rather to a group of like-minded artists coming together to a common place with a common purpose. In other words, an art colony. As one artist put it, the members of the Lyme Art Colony shared “a kindred feeling and common understanding as to matters and methods relating to art.”

The art colony at Old Lyme was part of a national trend

(as well as international) for artists, musicians, and writers to retreat from the modernity of the cities in search of solace and picturesque subject matter in the country. During the last decades of the 19th century and into the 20th century, painting colonies developed across America in such diverse places as Laguna Beach, California; New Hope, Pennsylvania; and Provincetown, Massachusetts. In each instance, the location of the colony provided the same necessary elements: desirable subject matter, access from the city via reliable transportation, inexpensive lodgings, a charismatic leader, and a sympathetic innkeeper.

Florence Griswold, c. 1915

In Old Lyme, this list was satisfied by the rural character of the local countryside,

the trains and ferries from New York, the Griswold boardinghouse, the jovial yet often dictatorial Henry Ward Ranger, and, perhaps most importantly, Florence Griswold. As one boarder put it, “Her optimism was unquenchable and her personality so persuasive that everyone who went there came under her spell.” Indeed, the Lyme Art Colony was to become one of the largest and longest lived of the American art colonies.

Henry Ward Ranger on side porch of Griswold House, c. 1900

The bottles of “MASTIC” and “RYE” are clever references to the two main activities of the artists while in Old Lyme, namely painting and relaxing. The nearly full bottle of mastic refers to a natural resin that would be mixed into the artists’ paints. The nearly empty bottle of rye refers to rye whiskey, an American-made liquor popular at the turn of the 20th century. Note that the bottle of mastic is corked, whereas the bottle of rye is shown open.

Bottle of Mastic - Artists at Work

The artists who traveled to Lyme were prepared to paint in the open air (or en plein air) or in one of the makeshift studios fashioned out of the neglected shacks and barns behind the Griswold House. In either case, they were confronted by the immediacy of nature. The artists would filter down from their various rooms at breakfast time, usually seven o’clock, to large pots of coffee, plates of eggs and bacon, and bowls of oatmeal, all fortifying ingredients for a day of studio work or outdoor painting. Then they would head off by foot, bike, carriage, or automobile in all directions in search of subject matter.

In June, when the mountain laurel was in bloom along the rivers,

the artists might head to the marshy banks.When autumn turned leaves crimson and gold, they might make their way into the rocky forest. Others would set up just outside the house, where “easels and umbrellas are likely to be found anywhere on the spacious grounds” to capture the sunlight on the river or the many flowers hidden among the tangled vines of Miss Florence’s gardens.

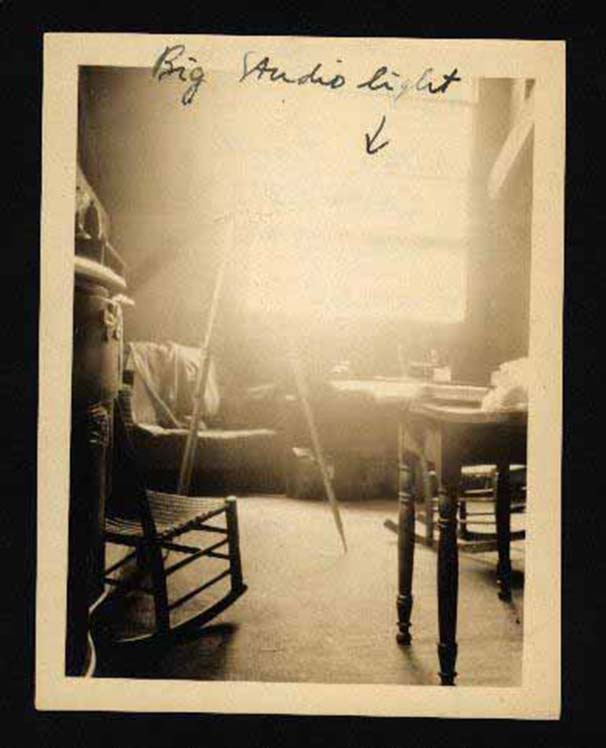

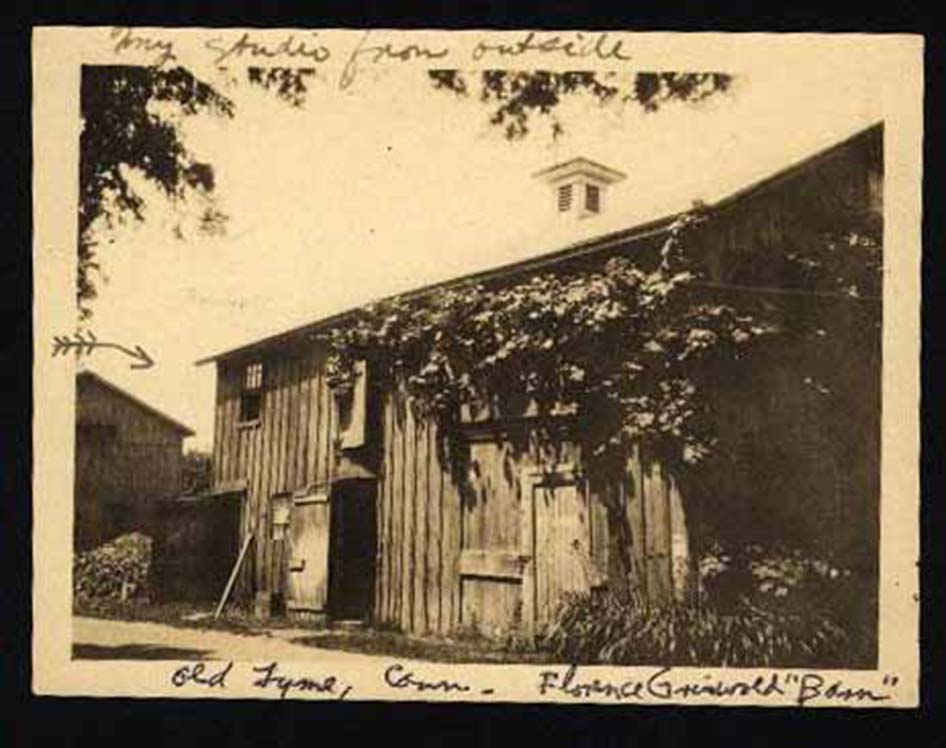

Barns behind the house were used as studio space

Photography and inscriptions by Jerry Bywater

Photograph courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas

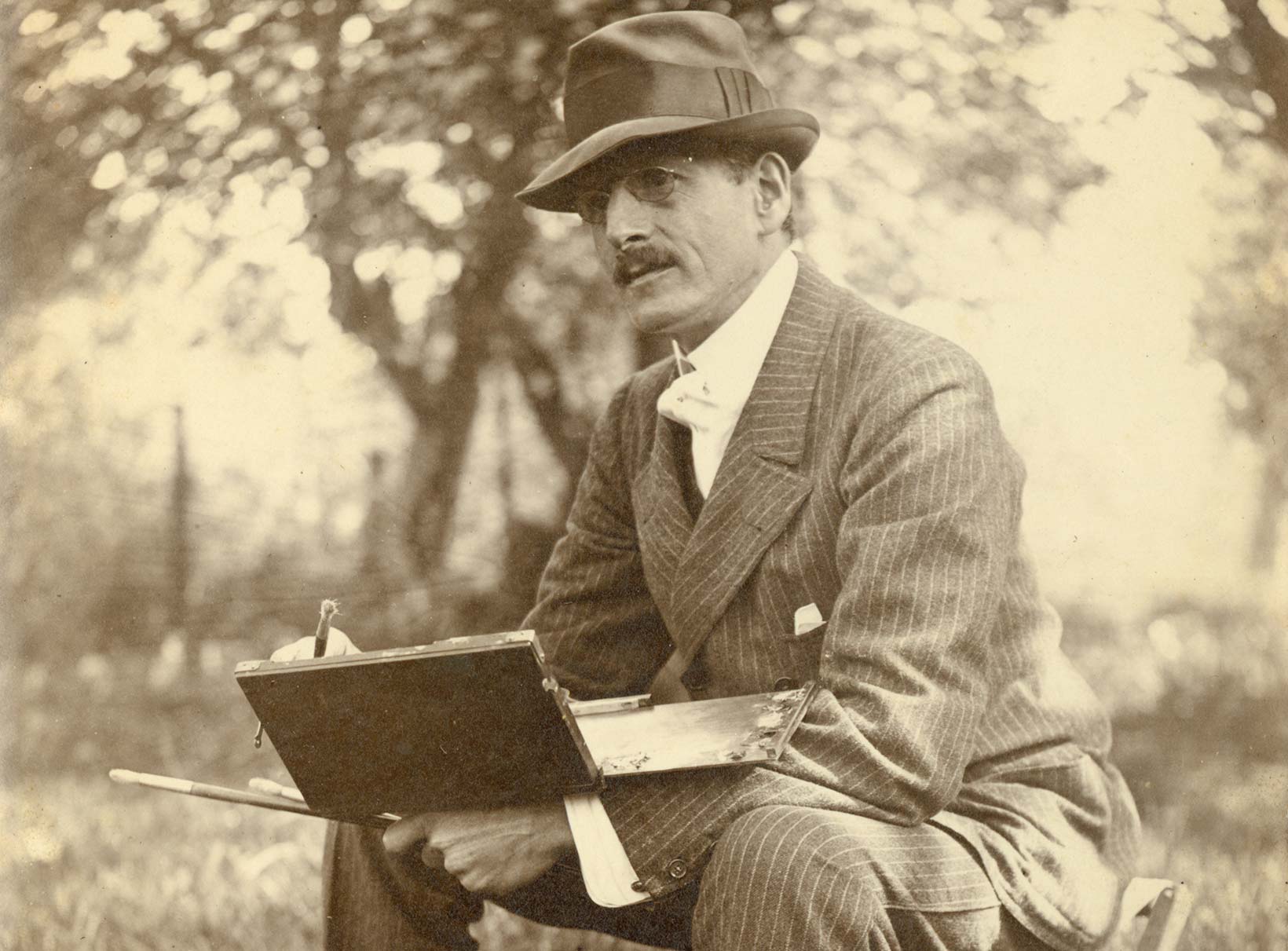

Wherever they worked, they would require all the supplies they needed for a day of painting,

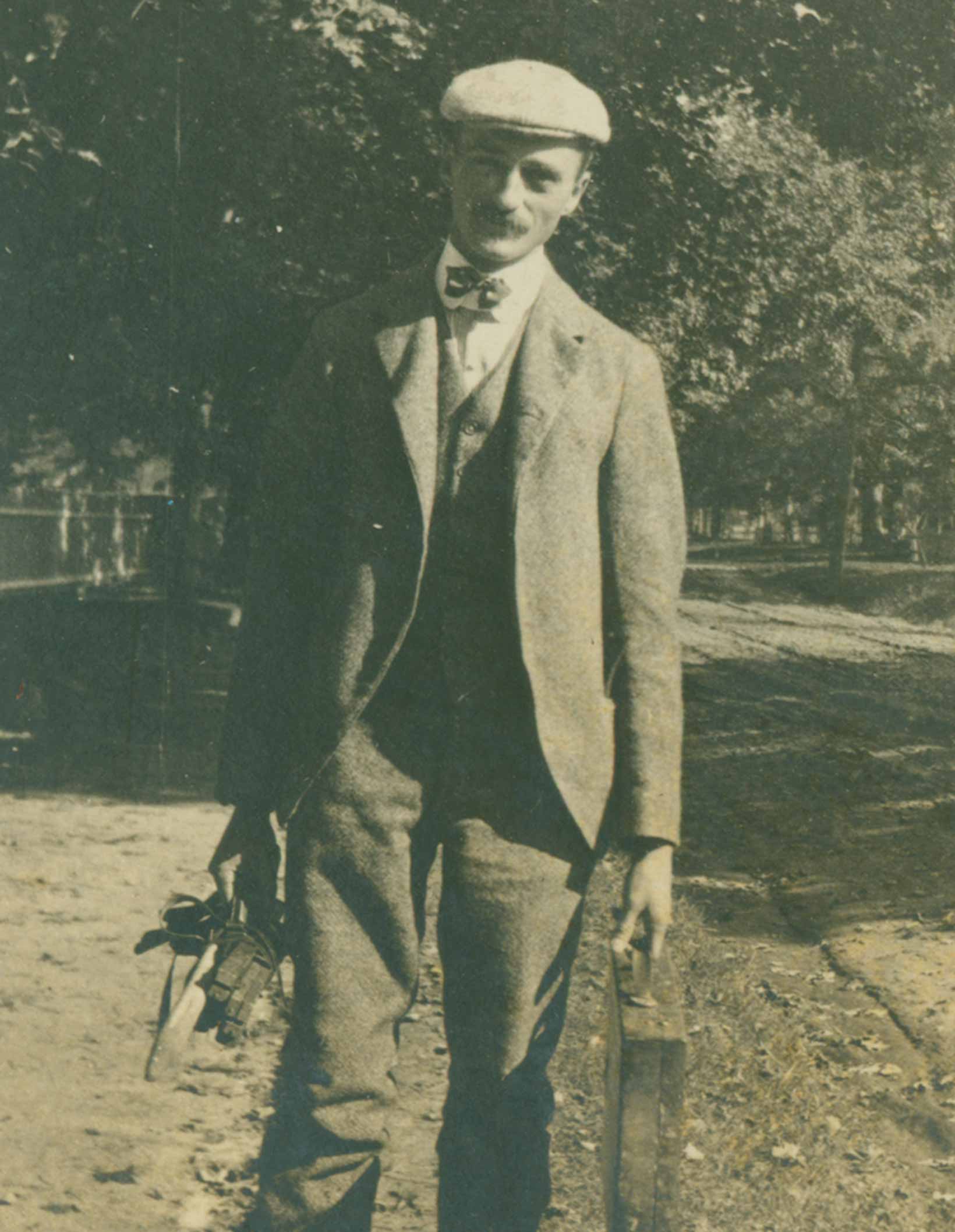

Clark Voorhees out for a day of plein-air painting, 1905

Painting En Plein Air

It’s not mere coincidence that the Lyme Art Colony flourished at the same time plein-air painting, or painting outdoors, became popular. By the end of the 19th century, an artist’s direct and immediate impression of a natural scene was often favored over their re-creating a landscape in their studio from sketches and memory.

To be closer to the desired subject matter the artists left their studios in the city and headed out to the country. Once there, they tended to congregate in the inns and boardinghouses available in the small villages and rural outposts. Old Lyme quickly became a preferred destination for many of these artists, and the Griswold boardinghouse and the surrounding grounds were perfectly suited to their needs.

Make-shift studios were fashioned out of barns and other outbuildings. Despite their tumbled-down appearance, these reclaimed buildings provided the necessary space where the artists could store their materials, stretch canvas, prepare panels, pack paintings for shipping, and even work on days not suited for painting outdoors.

These plein-airists, as they were sometimes called, ventured into the wilds unfettered by roof and walls.

They set up painting stations outfitted with their portable easels (ingenious contraptions that unfolded to full size and could be leveled on uneven terrain), paint boxes filled with squeezable tubes of paint, tins of solvents and oil, collapsible stools, and retractable parasols.

Summer painting class in Old Lyme, c. 1904

Some would bring canvas stretched over a wooden frame, others a wood panel to paint on.

Often the paint boxes were outfitted with grooves to hold the panels in place without smudging the wet paint while the artist was in transit. Visit the “Artists’ Tools & Technique” icon to learn more. The ease of such ventures was equally attractive to art students who, according to one report in 1904, “with umbrella and easel . . . seem to grow on meadow or hill, in the wooded paths or rocky slopes.”

Lewis Cohen painting en plein air

Painting in the Studio

Most of the artists who came to Old Lyme also had studios in New York or elsewhere. Both Henry Ward Ranger and Childe Hassam, leaders in the Lyme Art Colony, had studios in an artist co-op located on West 67th Street in New York next to Central Park. The studios had high ceilings and north-facing windows with spaces for sleeping and living. Unlike the contemporary notion of an artist’s studio, these spaces were often richly decorated, filled with carpets and domestic furniture, artistic knickknacks, and giant paintings in ornate gold frames. The situation was much different once the artists traveled outside the city to paint.

There were several painting studios,

“entirely casual affairs,” on the grounds of the Griswold boardinghouse that were crafted out of vacant barns and other outbuildings to accommodate her artistic boarders. Artists staying with Miss Florence could request studio space to use during their visit. The studio rent was as low as $5 a month. During a recent archaeological dig, the site of the studio that was often used by Childe Hassam was discovered to the northwest of the gardens.

Henry Rankin Poore in Studio with paint brush in hand and on table

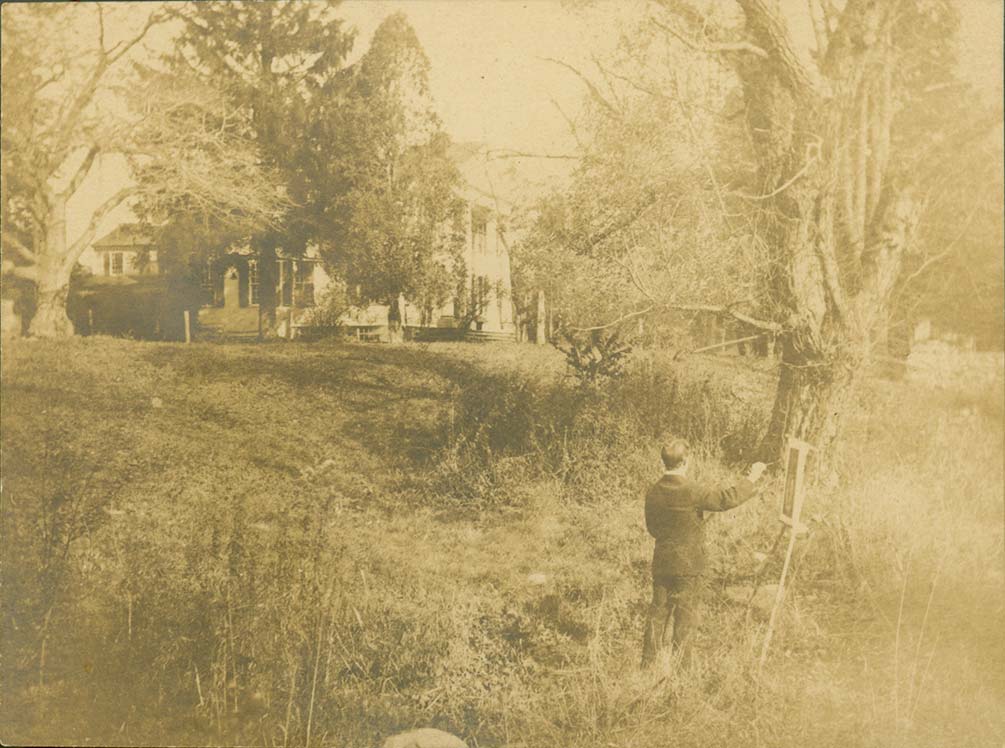

Nestled in the remains of an ancient apple orchard,

Hassam’s studio afforded views of both the river and Miss Florence’s gardens. Long-term boarder William Robinson also had his own studio on the property. Today, the Hartman Education Center stands on the site of an earlier barn structure that was also used as studio space, complete with a large north-facing window.

Childe Hassam near his studio

The studios were creative workspaces where the artists could prepare

and store their materials and work comfortably at any hour of the day or night. Despite the fact that the Impressionists, both in France and America, championed the notion of painting en plein air, or in the open air, most eventually returned to the controlled environment of the studio to complete a work of art, as well as to frame it or crate it. The first artists to stay in the boardinghouse worked outdoors but primarily with the intention of gathering visual information in a sketchbook or a painterly oil sketch.

“The object of study and sketching out of doors is to fill the memory with facts,” remarked one Tonalist Lyme painter. Likewise, Henry Ward Ranger, who is photographed on Mason’s Island painting beneath the trees, paradoxically remarked that “he painted in the studio because he could get closer to nature that way than by painting out of doors.”

Chadwick Studio

The studio of American Impressionist William Chadwick (1879-1962), a member of the Lyme Art Colony, has been preserved on the grounds of the Florence Griswold Museum.

Although not original to the property (the studio was moved to its present location in 1992 from elsewhere in Old Lyme), it demonstrates how an artist might organize his creative space. The studio has three main areas: workshop, studio, and loft. Originally an icehouse, the workshop area is filled with tools, canvases, frames and shipping crates. The studio portion was made homey with an area rug, wood stove, and desk with lamp. Chadwick was known to hang a sign on the studio door that read “resting” while napping on the soft daybed.

It is also a practical space for painting, with the large northern window,

a wide workbench for mixing pigments and organizing painting tools, and a model stand set with studio props. Chadwick was a talented figure painter as well as a landscapist, who worked in a high-key Impressionist style. Chadwick’s easel stands in the middle of the room displaying one of several facsimiles of his paintings.

Bottle of Rye - Artists at Play

At times the boardinghouse resembled a summer camp, where leisure activities filled the hours not consumed with painting, eating or sleep. Depending on the time of day or the weather, the artists would relax on the grounds or enjoy an excursion away from the property. Often, leisure activities would take place indoors, specifically in the front parlor after dinner.

Outdoor Leisure

Trips to the beach aboard a wagon, or up the river by canoe were common activities.

Using one of the artist’s motorboats the painters and their guests might venture up the Connecticut River and into Hamburg Cove for a moonlit summer evening picnic where they would eat sandwiches and grill chops on a campfire on the shore.

Artists on wagon heading to beach

However, the moon over the river was not always so innocent.

Willard Metcalf’s wife Marguerite had grown tired of her husband’s nighttime hobby of collecting moths by candlelight. Instead, she spent several nights floating in a canoe about the marsh with one of her husband’s students, the young and talented Robert Nisbet. She and Mr. Nisbet fell in love and ran away together in July of 1907 causing “a great scandal in the house.”

Parlor Games

About the merriment that happened at the boardinghouse,

artist Arthur Heming remarked that “entertainment was rarely ever planned. It just happened.” Often after supper, the guests gathered in the parlor for games and impromptu musicales. Music was an important part of the colony. Miss Florence played the piano, artists Harry Hoffman the flute or banjo, and Lewis Cohen the mandolin. Henry Ward Ranger was an accomplished organist. He had his organ shipped to Old Lyme from New York one season to add to these evening concerts. Unfortunately, Miss Florence’s English harp, a gift from her seafaring father, had been damaged and was not playable during the years of the art colony.

William Chadwick (1879-1962) Melodies, c. 1905

Oil on panel

Other parlor games were also popular.

Card games such as poker and bridge filled these leisure hours, as did spelling bees, charades, and amateur theatrics. The artists also devised their own parlor game called the wiggle game, a creative endeavor that championed their artistic skill and clever wit.

The Wiggle Game

The wiggle game was played by the Lyme Art Colony artists after a long day of painting.

The rules were simple. One player began by drawing several curvy lines, or wiggles, on a sheet of paper, using colored pencil. The second player would use the lines to create a funny cartoon-like drawing.

Lewis Cohen (1857-1915) Wiggle Drawing (monks reading scroll)

Graphite on paper

This game was both entertaining and educational as it challenged the artists to use their talents and their wits.

The images the artists conjured out of the random squiggles range from caricatures of the artists themselves to fictional characters such as a cowboy, debutante, farmer, and even Santa Claus.

William Chadwick (1879-1962) Wiggle Drawing (sailor with rope)

Graphite on paper