Collections

In Situ: The Painted Panel

- The Museum will be closed Thursday & Friday, November 27 & 28.

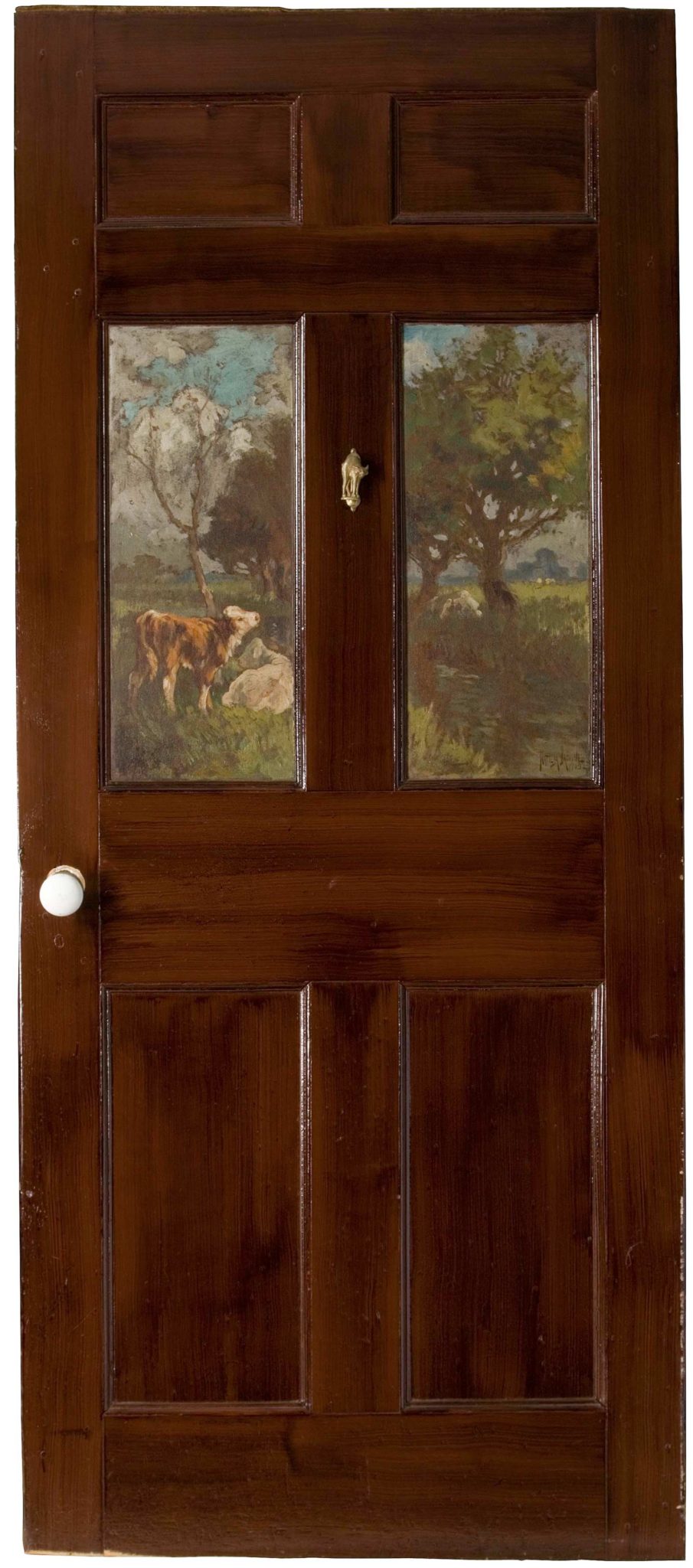

Matilda Browne (1869 – 1947)

Bucolic Landscape

Matilda Browne’s scene on Florence Griswold’s bedroom door resembles those that the art world of her day admired her for: a tranquil country landscape with cows. “Tilly’s cows” not only look alive but seem to have personality, as though one could go into a field and readily find the ones who modeled for the artist. Browne’s landscapes usually reveal her interest in light and shadow, seen here, for example, in the cloudy sky and in the way light strikes the cows on the left and the tree on the right. Like many artists of her time, Browne sometimes combined aspects of the two styles most popular then: Tonalism and Impressionism. Colors on this door are somewhat toned (she sometimes used bright ones), but her brushwork is somewhat loose and the composition is asymmetric.

Note the doorknocker in the shape of a cat. It was a later gift from the art colonists to try to console Miss Florence for their “reduction” of her large cat population, which had greatly exceeded reasonable limits. She had not had the heart to do anything about it herself.

Miss Browne had an extraordinary history. She exhibited at the National Academy of Design by age 12. She was a protégé of the famous landscapist Thomas Moran and the flower painters Eleanor and Kate Greatorex, and in the 1880s she had studied animal painting with Carleton Wiggins in New York, Julian Dupre in Paris, and Henry Bisbing in Holland. In the 1890s her paintings of cows and of flowers had been admired at the Paris Salon, won prizes at the World’s Columbian Exposition and the National Academy of Design, and been seen at expositions at Buffalo and St. Louis.

So it is no surprise that on her first visit to Old Lyme in 1905, the other artists at the Griswold boardinghouse asked Matilda Browne to paint on a door.

She was also the only woman to be included in The Fox Chase mural about the art colony that Henry Rankin Poore was painting over the dining room fireplace. These were extraordinary honors, since this all-male coterie generally looked down on female artists – exemplified by Metcalf’s Poor Little Bloticelli (1907). No other had even been invited to board at the house before.