Collections

In Situ: The Painted Panels

- The Museum will be closed Thursday & Friday, November 27 & 28.

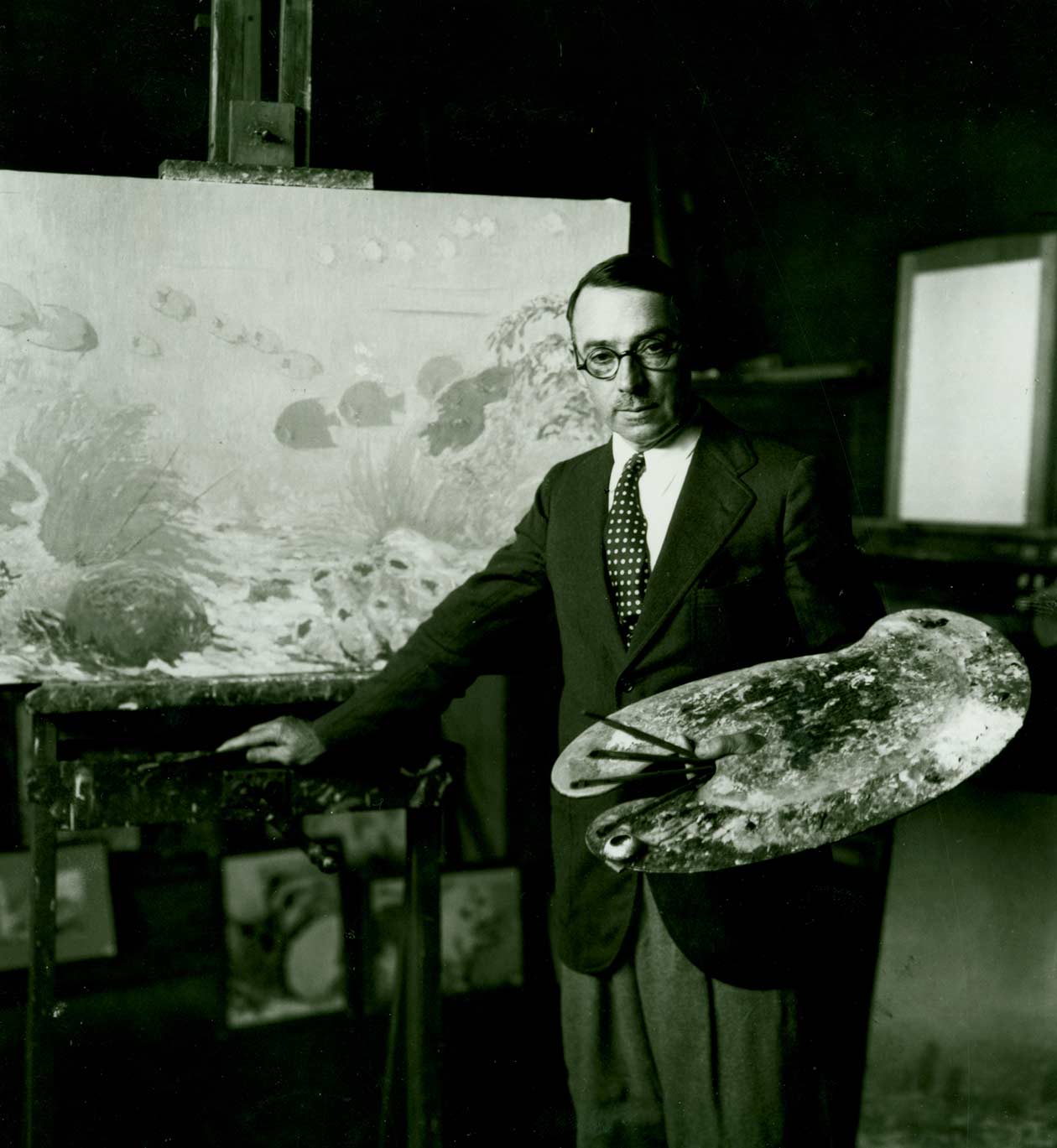

Harry Hoffman (1871 – 1964)

Woodland Stream – Autumn

In 1910, Harry Hoffman, who had been spending summers in Old Lyme since 1902, settled in the town year-round with a bride he had met at Miss Florence’s. Thus, unlike many of the art colonists, he was able to experience there a late fall day like the one he chose to portray on this panel. Limiting his subject matter mostly to bare trees, his perspective to a snapshot view, and his colors to a few earthy tones, he was nonetheless able to create a picture with a good deal of visual interest, rising mostly from the screen of varied tree trunks and bare branches. The eye discovers openings through which to see what lies beyond. At the same time the screen attracts attention to itself by the intricacy and diversity of its design, which seems always about to settle into the consistency of a set pattern but never does. The reverse side of this panel features a sketch of a landscape near rushing water, perhaps a first attempt to better relate to Heming’s panel nearby.

Landscape artists have always loved to depict trees that are beautifully shaped and in full foliage – ideal trees, one might say.

Real trees, however, are almost never perfect specimens, because any number of factors or accidents affects their growth. Hoffman makes us enjoy the resulting flaws – a branch bending at a crazy angle or otherwise going off in a direction seemingly of its own choosing. He allows us to savor the subtle variations of his trees’ basic browns and see how they blend with the tones of grasses, water, and sky on a subdued but not somber November day. Hoffman uses a similar approach in his painting that shows Miss Florence’s handyman James showing Miss Florence’s handyman sawing wood during a winter storm beneath a dramatic network of branches.

Hoffman’s panel is installed in the dining room above that of his good friend Arthur Heming, whose dramatic black-and-white Shooting the Rapids is immediately below. Heming took some credit for Hoffman’s success, because once, when Hoffman was so short of money he almost accepted an offer to pitch for a professional baseball team, Heming talked him out of it.

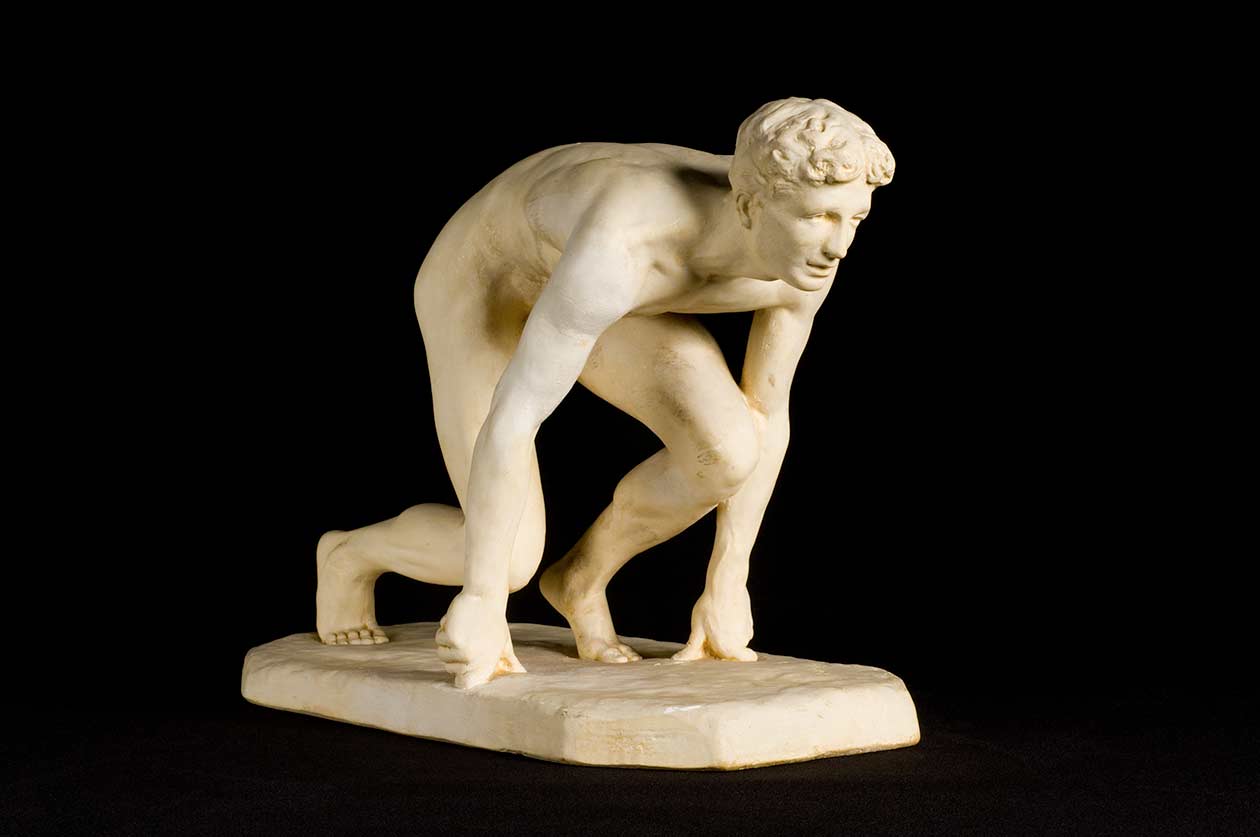

(Hoffman was quite athletic and posed for the sculpture titled The Sprinter (1902) by Canadian artist R. Tait McKensie (1867-1938), a cast of which sat on the bookshelf in the Griswold parlor during the years of the art colony.) Hoffman was also grateful to the artist Willard Metcalf for his valuable advice. Metcalf told him to forget the traditional art theories he had been taught and “go out and paint what you see.” This panel is a clear demonstration of Hoffman’s heeding those wise words.