June 3 – September 17, 2017

Flora/Fauna:The Naturalist Impulse in American Art

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

101 Works Surveying the History of Artists-Naturalists in America

Drawn extensively from the Museum’s collection, as well as many public and private lenders, Flora/Fauna surveys the history of environmentally-conscious artists in the United States from the dawn of the 19th century through the mid-20th century. The exhibition begins with early-American artists such as the Peale family, John James Audubon and their contemporaries, then examines the naturalist impulse in works by the Hudson River School, American Pre-Raphaelites, and American Impressionist artists before featuring select 20th-century artist-naturalists such as Roger Tory Peterson, creator of widely-used bird guides. Works in the exhibition reveal how artistic production corresponded with social developments in American history, from an early concern with establishing a national identity distinct from Europe; to reflecting Americans’ shifting philosophies on evolution and the human relationship to the environment; to the growth of the conservation movement in the United States.

The Artist-Naturalist in Early America

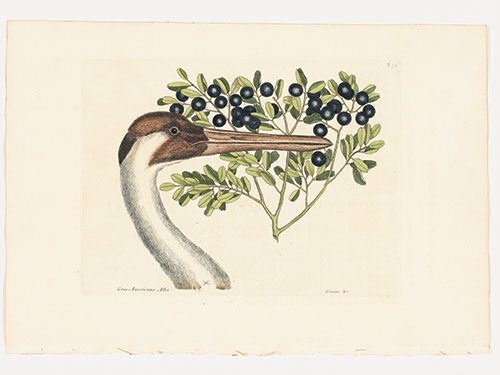

The birth of natural history in America coincided with the founding of the country. Such artists as Mark Catesby, William Bartram, the Peale family, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon participated in the American Enlightenment by pioneering many of the country’s firsts—the first natural history publications, institutions, and environmental experiments. Scientists quickly realized that they needed the assistance of artist-naturalists to give visual form to their discoveries and disseminate that knowledge through books, botanic gardens, lectures, and museum displays.

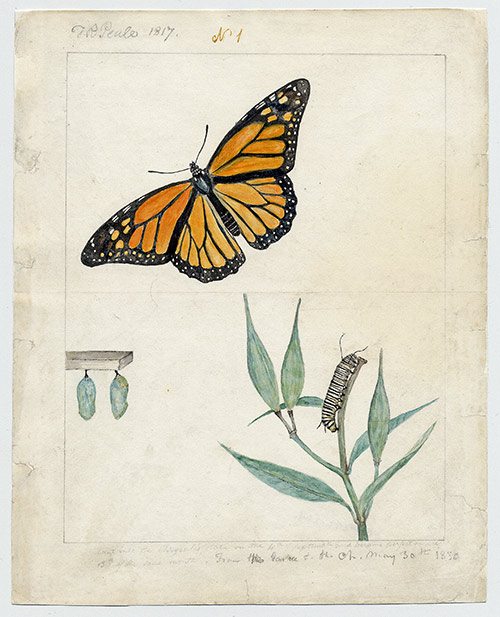

During this age of Enlightenment, many political leaders, including Thomas Jefferson, looked to natural history to help forge the identity of the new nation. Not surprisingly, the country’s first scientific center developed in and around its first capital. Philadelphia attracted the brightest intellectual, scientific, and artistic minds that formed a network of new professionals. Works in this section by the Bartram, the Barton, and the Peale families reveal that the forging of an American natural history was often a ‘family affair’ facilitated by personal relationships. Titian Ramsay Peale’s, Monarch Butterfly [No. 16], 1817 (American Philosophical Society Library) a work from an entomological sketchbook, demonstrates how artists participated in the discovery, documentation, and collection of natural specimens. The sketch shows the monarch at different stages of life. Beneath the illustration, he wrote his scientific observation: “Went into the Chrysalis state on the 4th of September—and became perfect on the 13th of the same month.”

Truth to Nature: American Pre-Raphaelites & Beyond

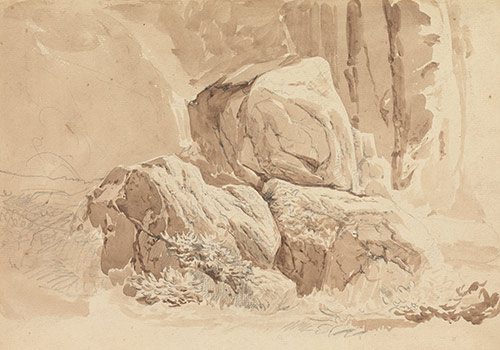

Many of the Hudson River School artists were aware of the writings of the English artist and critic John Ruskin, one of the most significant voices in the nineteenth-century art world. Ruskin’s works spanned a variety of topics from art, architecture, and natural history (including geology, botany, and ornithology) to religion, myth, and politics. His most influential and widely read text, Modern Painters(1843), emphasized the connections between art, nature, and society, and advocated for artists to uphold a “truth to nature” in their work. Ruskin’s pledge to a morally and socially committed art led him to reject the artifice of “decorative” art in favor of an art with an authentic source, such as nature itself. His followers in the United States, the American Pre-Raphaelites, produced landscape, still life, and studies that utilized a meticulousness of detail gleaned from their close study of nature en plein air.

Prior to his involvement in the arts, Ruskin had contemplated becoming a geologist. In the nineteenth century, geology was considered a gentlemanly endeavor that many artists, including the Hudson River School and the American Pre-Raphaelites, pursued. As works in this section show, careful studies exposing evidence of the artist’s process were as highly valued as finished works. In additional to geology, botany became an enormously popular genteel hobby, and developed into a status symbol. These pursuits enabled the success of nature illustrators like Fidelia Bridges, who brought these topics to mass-marketed periodicals and, thus, into thousands of American homes. A rare portfolio of Bridges’ work in the collection of the Florence Griswold Museum has been newly conserved and will be on view for the public for the first time. Ruskin and his American followers employed a scrupulous observation of nature from life in order to convey the ‘truths’ of their subjects’ identities, as seen in Bridges’s Thistle in a Field, 1875 (Florence Griswold Museum).

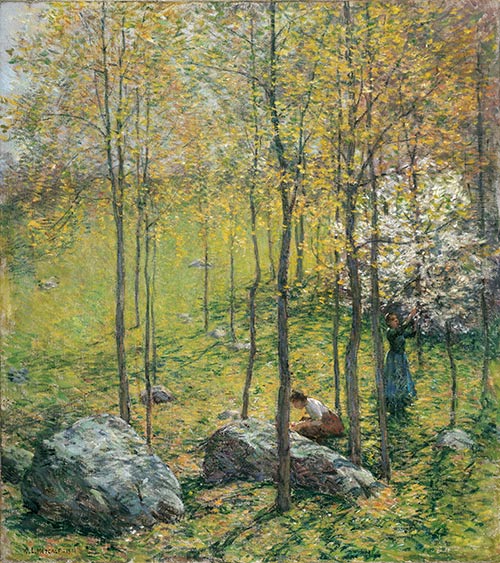

Impressionism & The Naturalist Impulse in Connecticut

While the “naturalist impulse” most often yielded a work of art that appeared naturalistic, or true to nature in a scientific sense, this exhibition allows for an expanded definition to include works that may be deemed “impressions” of nature. Like artists of previous generations in Europe, the American Impressionists found art colonies in the suburbs and countryside to be restorative retreats, where they could immerse themselves in nature and enjoy the camaraderie of like-minded colleagues. Around 1900, the natural landscape of Old Lyme perfectly fulfilled that need for artists. Not coincidentally, many artists who frequented art colonies, like Willard Metcalf, Childe Hassam, and Harry Hoffman, were also practicing naturalists, to varying degrees.

The consummate artist-naturalist of the Lyme Art Colony was Willard Metcalf. On view in Flora/Fauna is the cabinet housing his collection of specimens. One drawer contains thirty-eight glass-mounted moths, many with furry bodies and wings still displaying their original deep gold, bright yellow, or rosy pink pigments. A second drawer reveals thirty-two pink cigarette boxes containing the tiny eggs of such birds as the English Sparrow and the creamy blue eggs of a Redstart. Metcalf translated his love of the natural world to his artwork. He painted Kalmia (Florence Griswold Museum) in 1905, the first summer he stayed at Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse with the keen observations of one very much attuned to their environment. In Kalmia, Metcalf captures the smooth, blue Lieutenant River reflecting the calm sky, while fluffy white and pink blossoms and green grasses appear to breathe in the spring air.

The exhibition concludes with the artist-naturalist tradition that persisted into the twentieth century and still thrives today in the Connecticut River Valley. Roger Tory Peterson, who inspired the environmental movement with his activities as a naturalist, educator, and artist, purchased seventy acres of property in Old Lyme in 1954. Peterson published the first modern field guide, A Field Guide to the Birds; giving field marks of all species found in eastern North America in 1934 and developed the Peterson Identification System so that amateurs and professionals could identify species visually for close observation without hunting them. Satin Bowerbird, (Private Collection), created for reproduction in his 1964 book The World of Birds, is a simplified scene illustrating two birds interacting in their environment. These guides helped to popularize the pastime of bird watching and cultivate a national interest in wildlife.

Continued Awareness

When members of the Lyme Art Colony made nature the focus of their practice, they were drawing on an American tradition that began one hundred years earlier with some of the country’s first artist-naturalists and explorers. Today, issues of climate change, land conservation, and preservation of endangered species and habitats have acquired new urgency in the twenty-first century, making the chronicling of America’s natural history through art more relevant than ever. The Florence Griswold Museum remains dedicated to the pursuits of the artist-naturalist by fostering the understanding of American art with an emphasis on the art, history, and landscape of Connecticut.

Thanks to Our Partners

Flora/Fauna: The Naturalist Impulse in American Art has been made possible with the generous support of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, the National Endowment for the Arts, Bank of America, the Rudolph and John Dirks Fund of the Community Foundation of Eastern Connecticut, the Nika P. Thayer Exhibition and Publication Fund, and the Connecticut Office of the Arts. Additional support has been generously provided by a group of individual donors that are helping to advance the Museum’s mission through special exhibitions. Media sponsors: Connecticut Cottages and Gardens and WSHU.