The Great Americans: Portraits by Jac Lahav

February 9–May 12, 2019

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

Click here to download the exhibition brochure, which contains an interview with Lahav and a detailed view of the artist’s process as he moves from an idea to a finished portrait.

Click here to download the exhibition brochure, which contains an interview with Lahav and a detailed view of the artist’s process as he moves from an idea to a finished portrait.

The Great Americans has been made possible with the generous support of the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development, Connecticut Humanities, The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, and Bouvier Insurance. Additional support has been generously provided by a group of Exhibition Fund donors, as well as donors to the Museum’s Annual Fund.

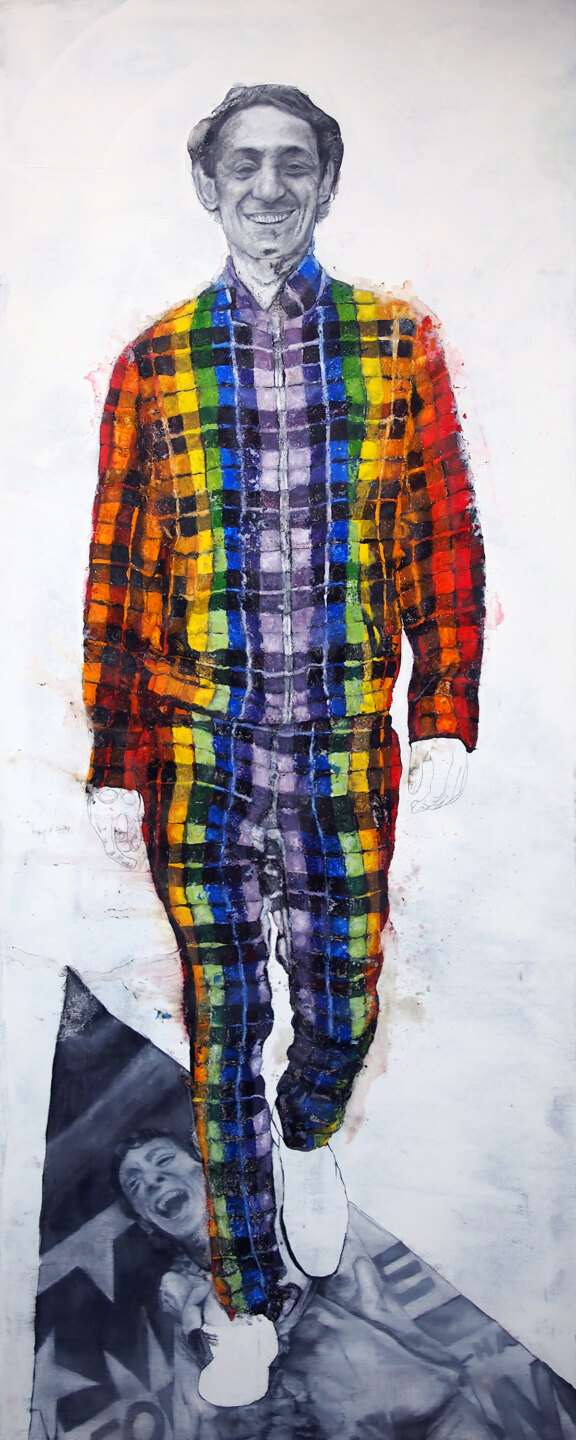

Who are our national heroes? Benjamin Franklin? Rosa Parks? Albert Einstein? Lahav’s nearly seven-foot-tall paintings of 30+ famous figures are a celebration of America layered with references to history, lore, and imagery that shape our understanding of these larger-than-life icons. Through his psychologically complex and cheeky treatment of iconic figures from politicians to celebrities, Lahav explores the nature of cultural identity.

Organized by the artist and the Museum’s Curator Amy Kurtz Lansing, The Great Americans explore the ideas of who we consider “great” and the cultural underpinnings of our perceptions (whether fact or fiction). Lahav created several new works for his series to reflect the evolving canon of American heroes.

Born in Israel in 1978 and educated at Wesleyan University and Brooklyn College’s MFA painting program, Lahav was inspired to begin The Great Americans portraits after watching a 2005 Discovery Channel series that asked viewers to select who they thought were America’s most notable figures, past and present. His portrait series, Lahav says, reflects “the push and pull between who are the people that we see as being great Americans and who actually achieved greatness.” Lahav’s work centers on oversized images of famous figures, whose updated costumes incorporate references from history, legend, art, and advertising that have shaped our collective perception of each person—or push against those perceptions. At the heart of the series is Lahav’s question to viewers about the validity of any canon, with their inherent value judgments and exclusions.

Gathering ideas and images everywhere from American folklore to Wikipedia, Lahav explores the painted portrait as a fabricated image, purposely including the sources we draw on for our cultural associations, whether factually accurate or not – ultimately asking what we can know about famous figures from their portraits and how much of it is true. Lahav’s artistic approach echoes the way that notions about historical figures can change over time—with new information effacing old legends and lore. The internet, especially Google’s top image search results, factors heavily into Lahav’s process and highlights the way that biography has been both shaped and distorted in the internet age.

The first section of the exhibition focuses on major historical figures such as George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy (with references to Barack Obama), and Jackie Kennedy. Lahav’s depictions of Lincoln, JFK, and Jackie in mourning track the way that subsequent presidents have assimilated Lincoln’s archetype—for example, through Jackie’s patterning of JFK’s funeral after Lincoln’s, or through the way that both Kennedy and Lincoln were invoked in relation to Obama, whose likeness surrounds an enthroned JFK. Lahav also takes on the myth of the frontier with portraits of Daniel Boone and Andrew Jackson. His portrayal of Jackson on horseback as the Marlboro Man intersects with current reexaminations of Jackson’s legacy with respect to the U.S.’s Western expansion. At the same time, Lahav contemplates portraiture’s lineage, incorporating visual references from modern artists such as Francis Bacon, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Gerhard Richter into paintings of JFK, Jackie Kennedy, and Lady Bird Johnson.

Another section addresses questions about how Lahav builds his portraits by sampling and layering images from the internet, then painting and overpainting to morph a figure like former Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice into author Edgar Allan Poe. The artist makes these changes in part to acknowledge that identity is fluid, with no one portrait ever summing up the entirety of the person depicted. Lahav’s fascination with medium and process, and his method of revising while he paints, invests history into each portrait as he works and re-works the surface, covering old images with new ideas. Just like the complex sitters themselves and our ever-growing knowledge about them, his portraits are like onions, built from many layers. Featured are portraits of Eleanor Roosevelt, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O’Connor, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Harvey Milk, Woodrow Wilson, and John Adams. The artist’s integral role in fabricating portraits is acknowledged in the likeness of Ginsberg, O’Connor, and Samuel Adams, which incorporate color-daubed artist palettes into the subjects’ clothes and accessories.

In The Great Americans Lahav also takes on the challenges of representing historical figures, especially ones who have been ignored in mainstream culture. He chose to paint a portrait of Charging Bear (aka Little Big Man) after finding that internet searches for the Lakota’s rival Crazy Horse yielded instead pictures of Charging Bear. Crazy Horse was never photographed, and in the digital age, images of one man have been substituted for the other by search engines with few noticing the difference. Rather than a conventional portrait image of Cesar Chavez, Lahav uses an alternate figure to represent the labor activist—drawing attention to the lack of awareness that often describes white Americans’ engagement with non-whites.

Lahav created several new Great Americans portraits for this venue, from Afong Moy (the first Chinese woman in America), to Martin Luther King, Jr., Harvey Milk, Charging Bear, and three sitters who spent time in Old Lyme—Woodrow Wilson, Albert Einstein, and Florence Griswold. The final gallery of The Great Americans includes his portrait of Florence Griswold (matriarch of the Lyme Art Colony). Lahav selected works by Lyme Art Colony painters and sculptors from the permanent collection, mining the museum to explore the idea of “six degrees of separation.” Extending out from Miss Florence, the pieces he has chosen reveal the network of Lyme Colony artists and establish links between them and people featured in his Great Americans portraits. One such connection is to Woodrow Wilson, whose artist wife Ellen Axson Wilson painted in Old Lyme. Mixing historic and contemporary art as well as paint-laden palettes, Lahav charts not only the ties between friends, rivals, pupils, and teachers but also the parallels of language and history that link a statesman-like marble bust of Miss Florence’s merchant relative George Griswold III to Lahav’s own portrait of George Washington and his Gilbert Stuart-inspired likeness of his pug, Instagram star Momo (@momopug2000). Sometimes irreverent or surprising, this expedition into what Lahav calls “the molasses of his mind” suggests the intricate ways knowledge accumulates and expands over time, narrowing the degrees of separation while informing our ever-changing views of historical and cultural figures in our technology-driven era.