Learn

Connecticut and American Impressionism

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

by Hildegard Cummings, independent art historian and curator

Connecticut and American Impressionism

Artists whom we call American Impressionists came to Connecticut in significant numbers at the turn of the 20th century. They found in this state a landscape that was intimate, rural, and soothing at a time when America had become urban, industrial, and restive.

The themes they explored were those first seen in the aftermath of the Civil War, when an intense longing for order and stability led artists to favor quiet, peaceful views over awesome wilderness vistas. Connecticut, with its longtime domesticated landscape and pre-Revolutionary history became then, for the first time, a significant place for making art other than portraiture.

The last of the Hudson River School painters abandoned mountains and gorges for Connecticut’s gentle hills and valleys and were soon joined by painters enamored of the evocative rural realism of French Barbizon art. Then the American Impressionists arrived and transformed a newer, more sensational French form into a thoroughly American art.

Images that spoke of comfort and hope to American artists and their public were still easy to find in Connecticut in 1900. Meadows, marshes, rocks, trees, rivers, and a sheltered shoreline; as well as historic New England buildings, homely dirt roads, well-worked farmlands, and old-fashioned gardens. Budding American Impressionists, keenly aware from their city life of the onrush of modernity, may have appreciated an intimate countryside even more than their predecessors, knowing, as they did, that much of it had already disappeared. Ironically, the intrusive technology of rail service, electricity, and plumbing made it easy for them to come and absorb the timeless qualities that remained.

Connecticut’s rural charms, however, might not have been enough to attract the hundreds of artists who painted landscapes here from the 1890s into the 1920s had it not been for an art collector named Erwin Davis in 1882. He so badly wanted a picture owned by artist J. Alden Weir that he offered him a farm in the Branchville section of Ridgefield. Weir accepted, and when his friend John Twachtman joined him there in the summer of 1888, the two pioneered a new way of seeing the landscape. Their outdoor experiments were aimed at translating the spontaneity and delicacy of watercolors and pastels into the oil medium and at incorporating the colors and flattened perspectives of Japanese woodblock print designs. Etching experiments also prompted them to rethink the expressive possibilities of line.

When the two exhibited together in New York the following winter, critics saw that they had cut loose from traditions of the previous two decades and predicted that people would find it hard to accept “the shorthand summary of these ultra impressionists.” In 1893 the two exhibited jointly again, this time in direct competition with art in an adjoining gallery by Claude Monet and Albert Besnard.

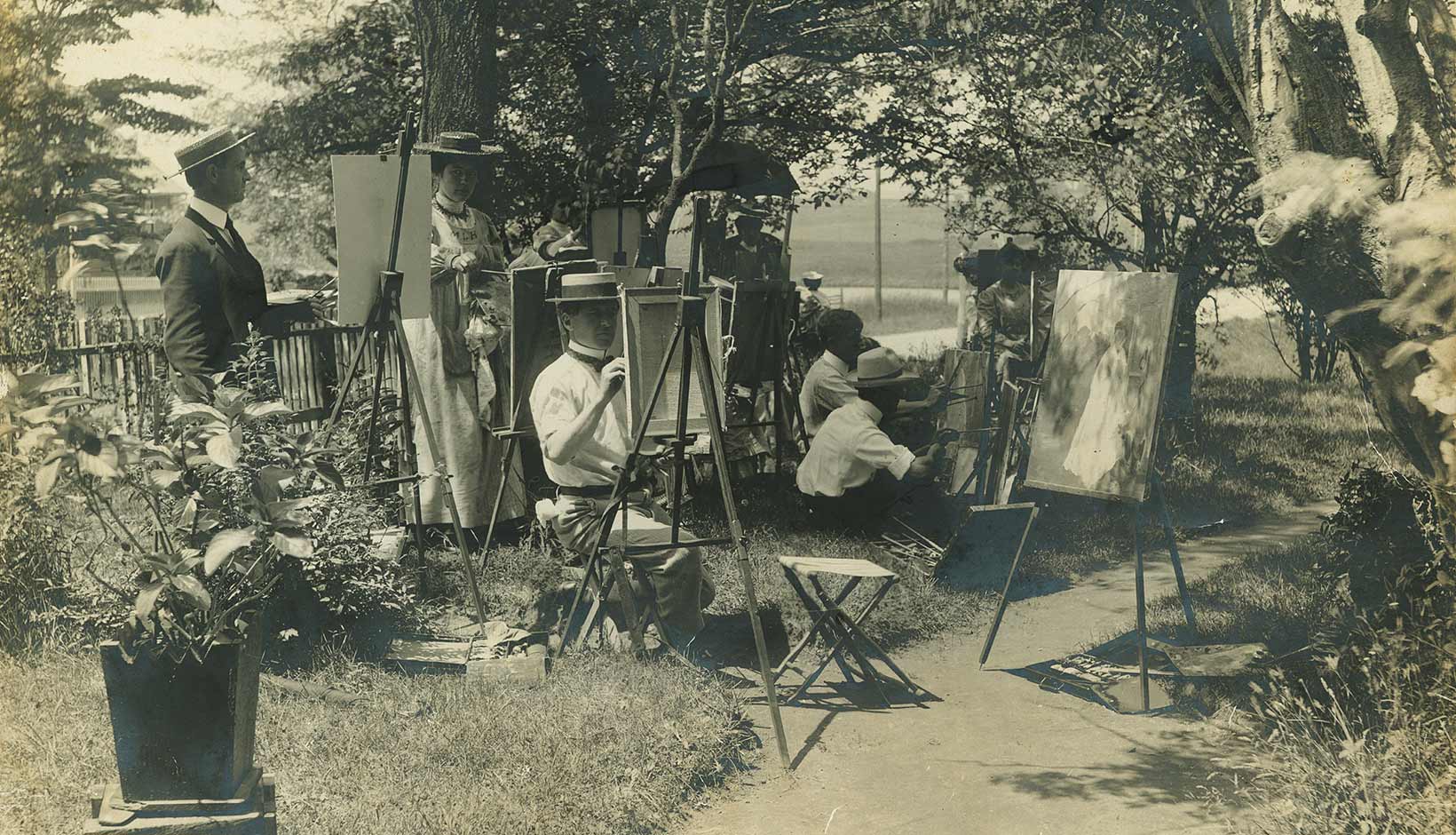

Twachtman had settled on a farm of his own in Greenwich by 1889, within visiting distance of Weir, and in about 1891 began teaching summer classes in the Cos Cob section of town. Whether he intended it or not, he had found in the small maritime village one of the prime requirements for the development of an art colony like those he and his friends had experienced abroad: a pleasant, inexpensive place in the country for a group of like-minded artists to live, with landlords who fostered an atmosphere conducive to fruitful discussion and work. Thus a boardinghouse run by Edward and Josephine Holley became the center of an art colony led by Twachtman, in association with J. Alden Weir, Theodore Robinson, and Childe Hassam. These artists, hailed today as masters of American Impressionism, participated in shaping an art inspired by French Impressionism that was not only intensely personal but deeply rooted in American landscape traditions and in the national reverence for nature. Fellow artists and art students learned from these mentors, embraced their experimental spirit, and disseminated their views to others.

The art colony at Old Lyme began in 1900.

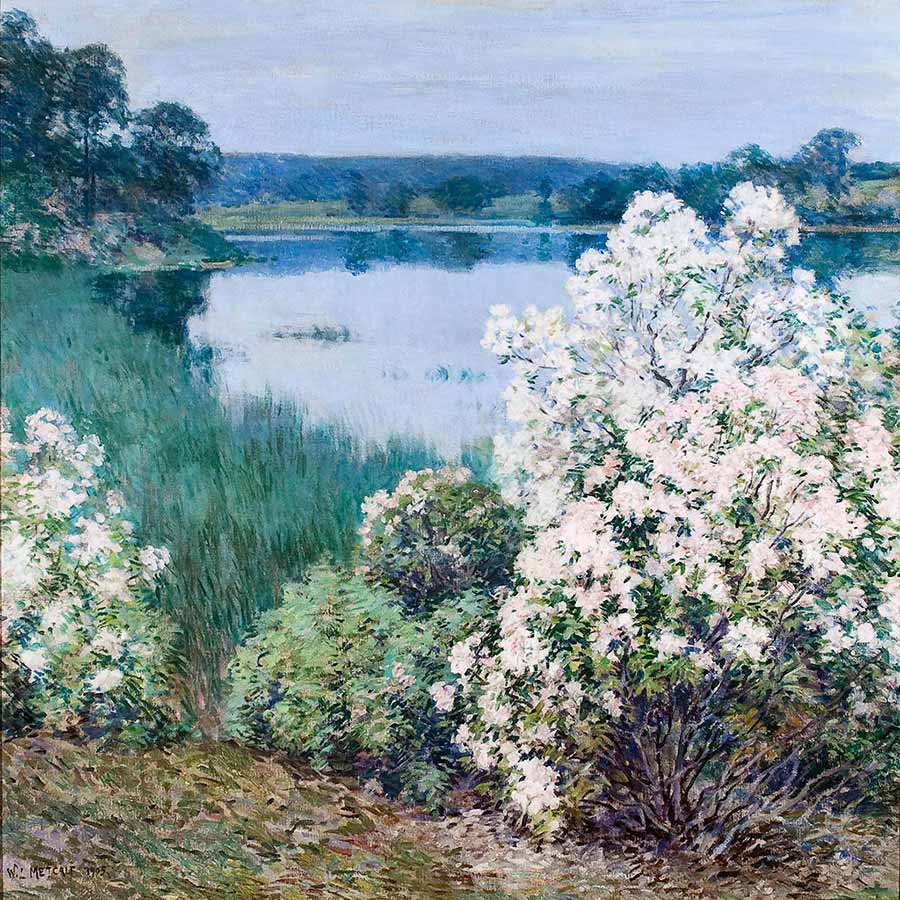

Centered in the boardinghouse of Florence Griswold, founder Henry Ward Ranger wanted it to be an American Barbizon, but the focus changed to Impressionism after the arrival of Childe Hassam in 1903. He stayed only until 1907, but Willard Metcalf, Allen Talcott, Walter Griffin, Frank DuMond, Will Howe Foote, and others, whose reputations were made in large part by their Old Lyme paintings, would continue to lure artists to the town. In 1902, fourteen Old Lyme pictures were in New York’s National Academy of Design annual. Moreover, the colony instituted that year an annual summer exhibition, a first for an American art colony.

It took place in the town library, where bookshelves were draped so that paintings could be hung. Tea was served on the lawn, and trains and boats brought droves of people from out of town. Newspapers and periodicals all over the country soon ran reviews, and Old Lyme became the largest, best-known Impressionist art colony in the nation. In 1921 the Lyme Art Gallery opened next door to the Griswold house. It was the first to be financed by a summer art colony.

Not all Connecticut Impressionists were art colonists. J. Alden Weir was briefly associated with Cos Cob when he taught classes there with Twachtman, but he preferred to paint at his Branchville farm (and another in Windham, inherited from his mother-in-law), where, in the course of 40 summers, he hosted artist friends. An artist who aggressively promoted Impressionism was the dashing Dawson Dawson-Watson, an oddly-named Englishman who came from Giverny, France, in the early 1890s to teach at the Hartford Art Society. He exhibited Impressionist images that he painted in nearby Farmington, taught Impressionist precepts to his students, and gave public lectures about this art, which had evolved in France some 20 years earlier but was still misunderstood in America. Hartford was bewildered, but art students were enthralled. Allen Butler Talcott, a future luminary at Old Lyme, was a friend and painting companion. Dawson-Watson soon moved on but was the talk of the town for years afterward.

In Mystic in the 1890s Charles Harold Davis, whose Barbizon paintings were widely admired during his long stay in France, was responding to the different light and color of his new locale. Students came to learn from him, and he persuaded colleagues to move to town. Artists and easels became common sights along the Mystic River, the streets, and in the hills. At the same time, artists were painting impressionistic scenes in Farmington and in villages in the Litchfield hills, and others were scattered throughout the state. Connecticut’s small size and good rail system made it easy for artists to know what their peers were doing. Most had, besides, winter studios in New York City, were fellow members of art societies and clubs, and exhibited in the same exhibitions.

It seems clear nonetheless that American Impressionism would not have blossomed so fully in Connecticut had it not been for the art colonies at Cos Cob and Old Lyme. Located out of the city, but within easy reach of it, in places rich with homely subject matter, and centered in boardinghouses managed by people sensitive to artists’ needs, these art colonies provided stimulation that only living communally and working in close proximity can offer. Students may have hovered and townspeople gawked, but such nuisances mattered little to artists when an inspirational star like Twachtman or Hassam was in residence.

The American Impressionists were sophisticated and well-traveled and did not completely reject urban life or modern marvels. At the turn of the 20th century, however, American cities and industries were expanding at dizzying rates, and a host of immigration, labor, and other problems were causing widespread unrest. Poised on the brink of world greatness, America was both headily optimistic and terribly nervous, afraid of losing the values and characteristics that had made it special.

The American Impressionists felt this as keenly as anyone, perhaps even more so. New England’s landscape and cultural character appear to have offered them (and their public) a hope that the best of America would survive. The French Impressionists celebrated in their new modern urban and suburban lives, but the Americans looked instead to a New England countryside like that in Connecticut for evidence of a stable, timeless order beneath the dazzle of the ephemeral.