Hauling and Harrowing

About Edward C. Volkert

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook

The Biography of Edward Volkert

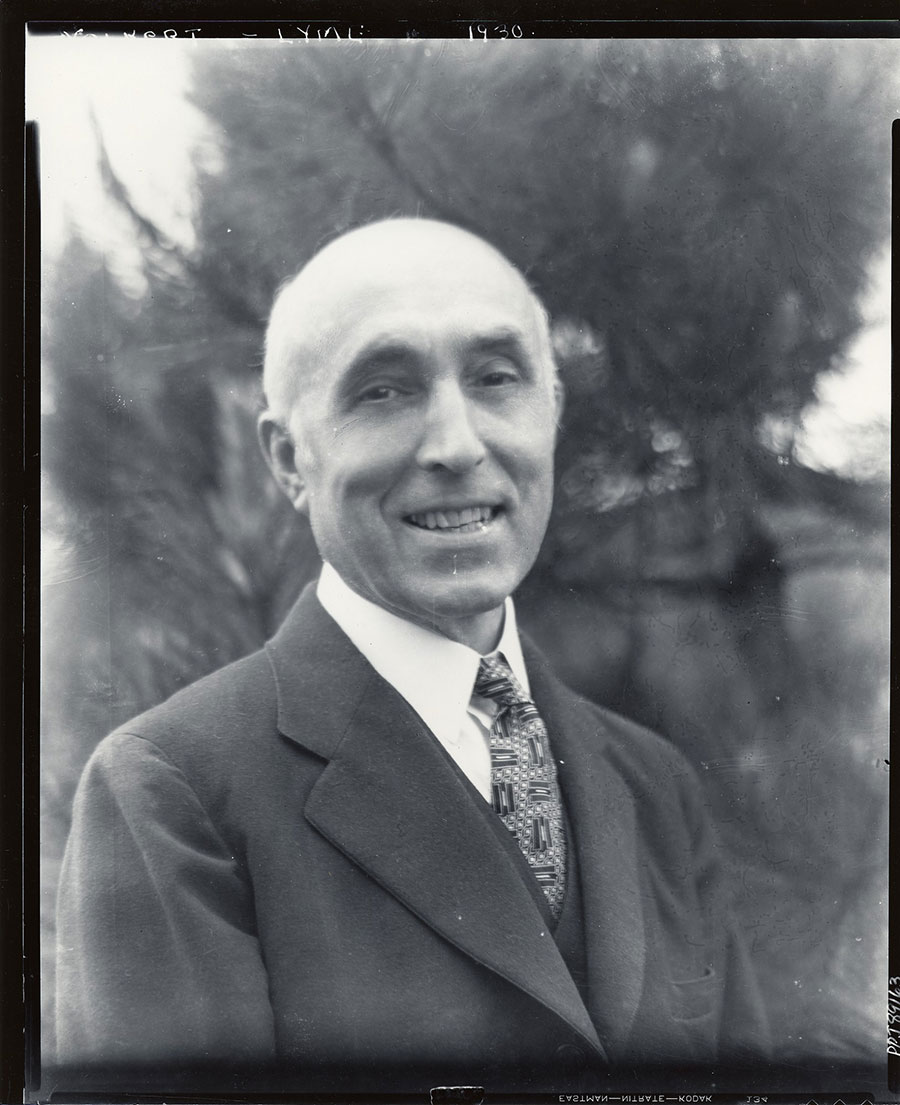

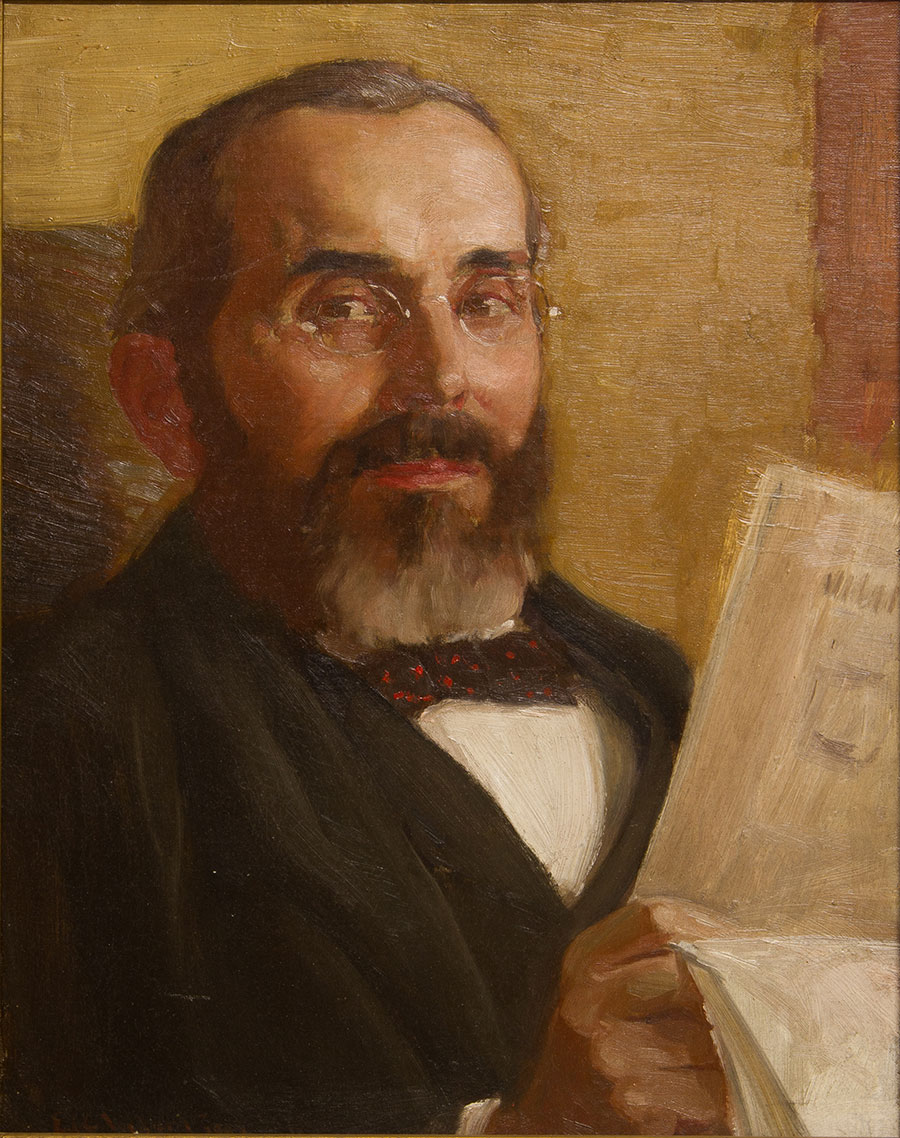

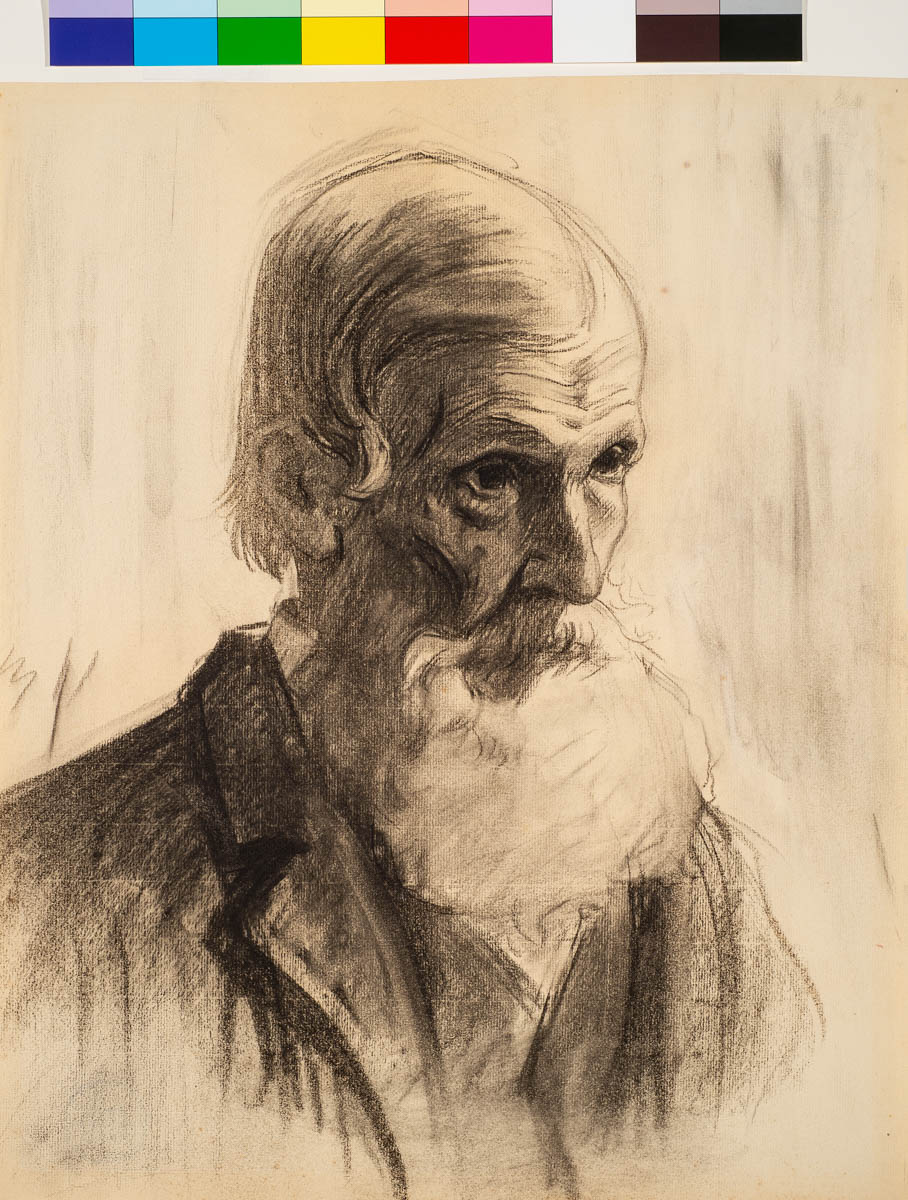

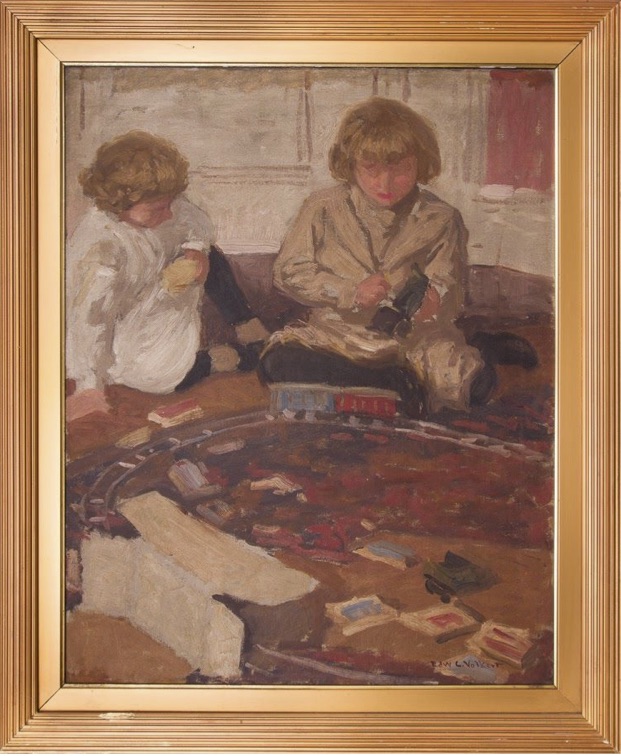

Edward Volkert was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of Phillip Volkert, an immigrant from Alsace who made silk hats, and Catherine Dair, who was from a family of Bavarian immigrants(1). One of his sisters, Clara Volkert, also became a professional artist. He attended Woodward High School, followed by the Ohio Mechanics Institute and is listed in city directories of the early 1890s as “Designer.”(2) He studied under Frank Duveneck at the Cincinnati School of Art, building a foundation in academic drawing before moving by 1898 to New York. There, he spent time at both the Art Students League, where he held the Duveneck Scholarship, and the National Academy of Design under teachers William Merritt Chase, H. Siddons Mowbray, and George DeForest Brush. Examples of academic studies from Volkert’s student years show his mastery of the human figure, which informed a small number of portraits that bookended his career, as well as demonstrating the commitment to anatomy and form evident in his many depictions of livestock.

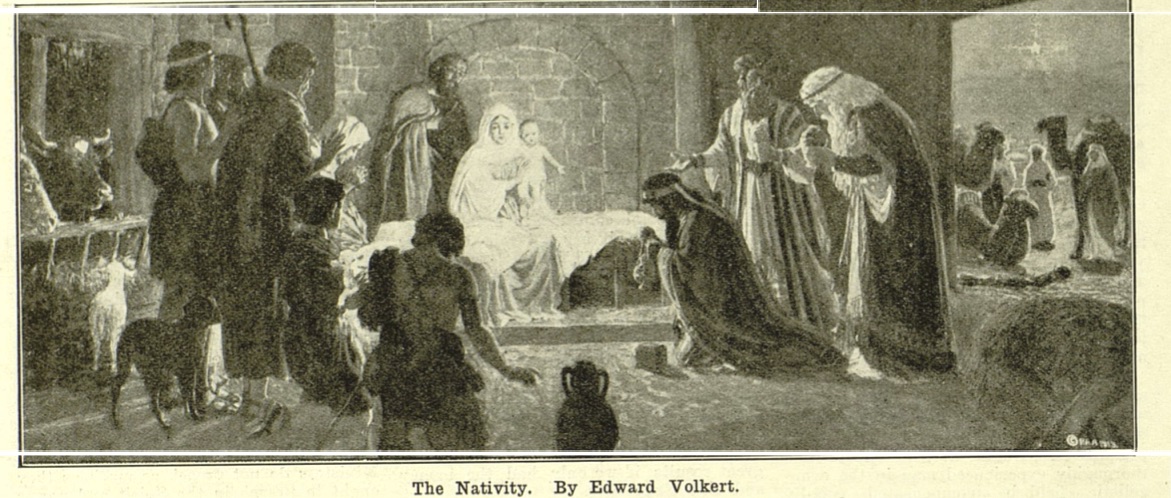

The artist exhibited watercolors as early as 1897, showing at the New York Water Color Club what the Art Interchange described as “a night market scene in the streets of the Jewish quarter of New York.”(3) He offered his work for view in 1898 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He exhibited at the National Academy of Design beginning in 1906 and continued into the 1930s. While the artist would steadily build a reputation as one of the country’s leading cattle painters over the course of the 1910s, the responsibility to support his family after marriage to Jessica (Jessie) Willis in 1897 and the births of children Robert and Ruth in 1898 and 1899 necessitated that he work as a commercial artist. He maintained this role for several years after divorcing in 1907. Jessie returned to Cincinnati with Ruth, while Edward had custody of Robert, raised with his mother’s and sisters’ assistance. Volkert served as the chief artist of United State Printing and Lithographing Company in Cincinnati, producing content for schools, churches, and even a widely distributed billboard.(4) Despite his regular presence in the city and legal efforts to regain custody, he was cut off from contact with his daughter for the next decade.(5)

Volkert’s dedication to the theme of cattle in his work has been explained as evidence of his disenchantment with his fellow man after his divorce. However, his oeuvre shows that his emphasis on livestock in his landscapes began before that break. Rising early to capture light effects in a landscape painting one day in 1903 near his residence in the Bronx, he approached Schneider’s dairy on Boston Road. There, he “saw a group of cattle browsing in the sunshine, which so appealed to him as a fine composition that he made a study of it…. since then he has painted little else.”(6) Questioned often about the theme, the artist explained the merits of his subject thus, and even specified his preference for oxen over cows:

“Oxen are twice as good as cows at posing. Oxen are wonderful. They are always willing to stand still. Cows are more inquisitive—that is their feminine temperament, I suppose…. Oxen, on the other hand, are impersonal and totally devoid of interest in mere humans. However, they instantly recognize the word of greeting to their driver and stop of their own accord to permit him to gossip with a passing neighbor. They are willing to stand still indefinitely.”(7)

While cattle made ready models for Volkert, he remained committed to the exploration of light and atmosphere on his canvases. The titles of his paintings refer as readily to times of day or seasonal conditions (for example, June Morning), as they do the grazing or resting of his bovine models. To suggest the atmospheric effects of light, Volkert applied high-key color in mosaic-like bits. Dark and light dabs of paint morph into animals forms as well as patterns of sun and shadow. The artist’s embrace of forceful color and illumination found appreciation among critics as fresh and vital, but also flouted assumptions for rural scenes in which the non-local color was unexpected by some viewers, including a writer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle: “The impossible purple cow of legend and story does indeed exist, if we can trust Mr. Volkert’s color vision, but I am inclined to believe that purple is an idiosyncrasy of the artist, as his distances and his shadows are steeped in the same lavender hue.”(8)

Like other traditional American painters responding to the 1913 Armory Show that introduced European modernism and in the aftermath of World War I, Volkert actively sought exhibition opportunities in the ‘teens and 1920s. Venues where he showed ranged from New York’s Milch Gallery, to the Cincinnati Art Museum, to artist-run organizations such as the National Academy of Design (NAD) or the Lyme Art Association (starting in 1925), to state fairs in Ohio, Georgia, and Minnesota. He collaborated with other painters on the creation of Allied Artists of America, founded in 1914 as a venue for artists to display their work without the constraint or discrimination of juries. He also exhibited with like-minded artists in groups called The Painter Friends and Six American Painters. These non-competitive alliances were designed to solicit the interest of gallerists in their traditional approach, and to package their works for distribution to other cities through organizations like the American Federation of Arts. Records Volkert kept about his paintings indicate how extensively he circulated them to exhibitions, finding purchasers across the Midwest as well as in New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. He gained associate status at the NAD in 1921, coinciding with his most active decade. The added prestige of that designation likely contributed to his success in the market during those years.(9)

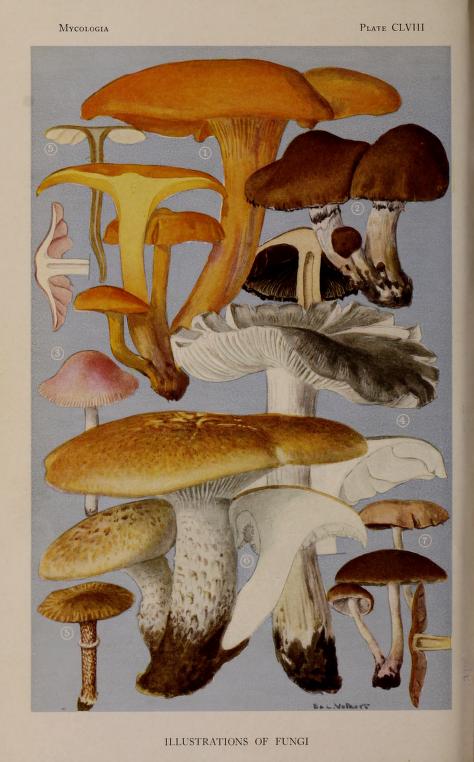

Volkert’s career took him from Cincinnati to the northeast, and he moved often between those locales until the end of his life. Work remains to be done to build a chronology of his art correlated to his travels, but he sought out cow pastures both in Ohio and in the northeast. As a young professional in New York, he lived and worked in Manhattan. After his divorce, he resided in the Williamsbridge section of the Bronx, where proximity to his housemate—the naturalist and leading mycologist William A. Murill—and to the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) allowed him to maintain a connection to the natural world. He helped discover and document mushrooms, contributing both illustrations to Mycologia, the journal founded by Murrill, and specimens to the NYBG.(10) Later, the artist found access to nature in the Catskills, and placed compositions of cattle against its rounded mountain tops. While he still boarded with Murrill in the Bronx in 1920,(11) by 1922, he had obtained a summer place in Lyme, Connecticut, on Sterling City Road. Next door lived another Midwestern transplant, artist Wilson Henry Irvine, who along with George M. Bruestle and Guy Wiggins of Lyme had been members with Volkert in The Painter Friends. Positioned overlooking a hilly vista, the property gave Volkert the opportunity to paint the area’s bovine herds just steps away from his door.

Volkert kept records of his own works, in the form of sketches of roughly 1,000 finished pieces that he called his “Cattle-Logs” (microfilmed by the Archives of American Art)(12). The sketches (in watercolor, oil, and crayon) are scale replicas, and the artist estimated that he had spent up to a year of his life on this document. The watercolors were found in his Lyme studio after his death and consist of loose-leaf pieces of watercolor paper, 8 x 10 inches.(13) Volkert made the catalogue for practical reasons, to track his oeuvre and to allow the option to duplicate compositions if desired by a new buyer. To the images, Volkert added notes on the original works’ sizes, occasionally identified where they were painted, listed where and when they were exhibited, indicated whether they were sold and to whom, at times including the address of the purchaser. Further study of the “Cattle-Logs” will certainly yield discoveries about where Volkert painted, help establish a chronology for his work, and refine our sense of the market for his vivid agricultural landscapes in the 1910s and 1920s.

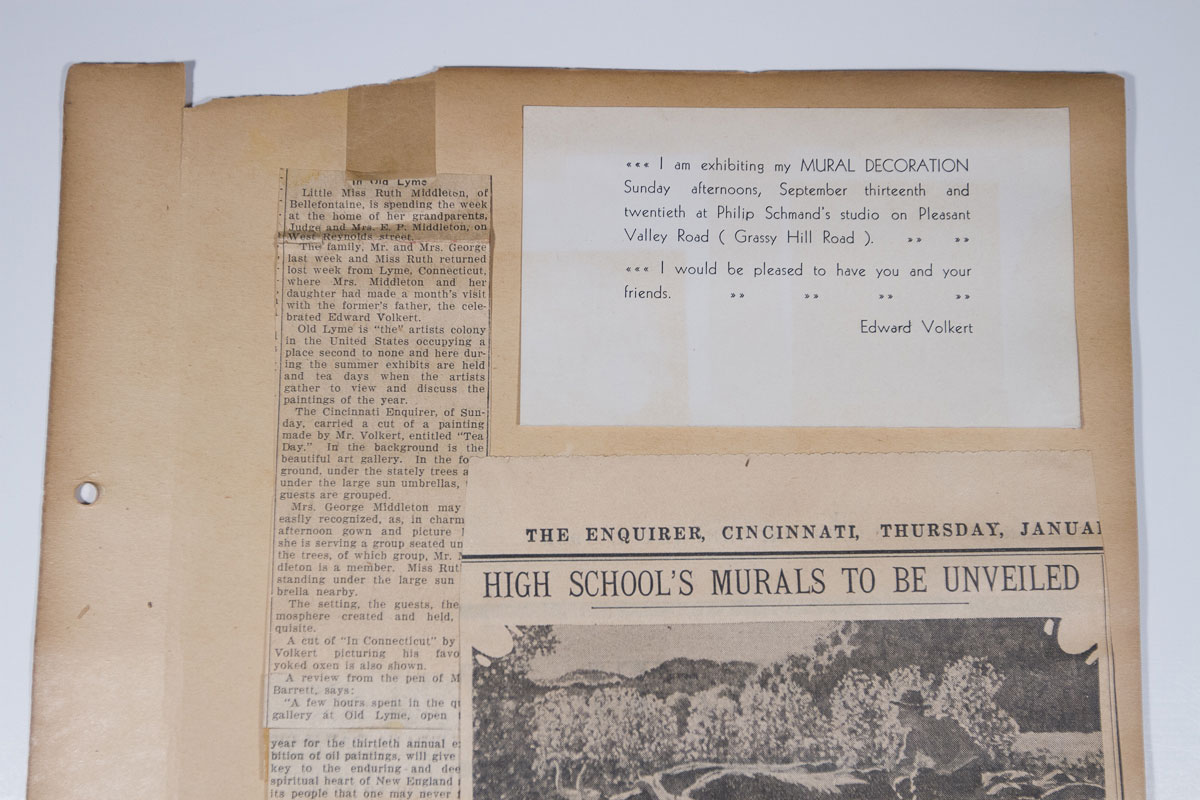

Volkert’s years in Lyme were productive, allowing him to practice his workman-like ethic of rising before dawn to capture the atmosphere and early light over the pastures. His granddaughter described the regularity of his routine as Zen-like in its alignment of the artist and his bovine subjects, after whom he could trek for hours with little thought to his own fatigue. When not painting, he socialized with the community of artists, as well as with friends from the world of theater and film, who congregated in and around Hamburg, a section of Lyme, sharing a mutual interest in gardening.(14) When the Lyme Art Association’s (LAA) gallery opened in 1921, Volkert served as the organization’s secretary. He was among the artists who contributed works on paper to a portfolio assembled in 1928 in honor of the Association’s patron, Chicago philanthropist William O. Goodman. His affection for the LAA prompted him in 1931 to complete Tea Day (Private Collection), a painting of portraits of fellow artists and visitors to the annual summer exhibition enjoying refreshments on its lawn. The LAA’s esteem for Volkert manifested the next year, in 1932, when he won the Mr. and Mrs. William O. Goodman Prize for a group of small oil sketches. When not helping to build the LAA gallery’s reputation, the artist made time to decorate his Lyme studio with a series of landscape paintings on panels that could be rearranged for each season.

In the early 1920s, Volkert reunited with his daughter, who, like him, was a trained artist. The restoration of family relationships surfaced in his work in the form of several portraits, at least one of which he exhibited. The artist continued to work until the early 1930s, completing large mural projects for two schools in Cincinnati, but the unexpected death of his daughter Ruth from diabetes in 1932 devastated him. While in the city with family, he became ill with uremia, a sign of kidney failure from renal disease. A Christian Scientist, Volkert was admitted to one of the faith’s nursing homes in Columbus, Ohio. He died there on March 4, 1935, and is buried in Cincinnati.(15)

Footnotes

- Artist’s biography, Volkert Artist’s File, Florence Griswold Museum.

- Cincinnati City Directory, 1892. Accessed via Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- “Water-Color Club Exhibition,” The Art Interchange 39, no. 6 (December 1897).

- On Volkert’s employment, see “Billboards and Religious Pictures,” The Churchman, January 3, 1914, p.1 (link)

On an innovative billboard he designed in 1913, to spread a Christmas message rather than a more conventional advertisement, see “Billboard Owners Preach by Great Pictures,” The Continent, December 25, 1913, p. 1818 (link) - Volkert’s suit for custody of Ruth was ongoing in 1909, when the Cincinnati Enquirer reported on questions about the character and suitability of Jessica’s second husband, the Swedish tenor Tor Van Pyk. “News of the Courts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 17, 1909, p. 10. Jessica Volkert had originally sued Edward for divorce in 1907 in Spokane, Washington, where she was living with Van Pyk, citing cruelty and seeking custody of their daughter. Edward Volkert successfully fought the 1907 Washington custody judgment, which was reversed in 1909, but appealed by Jessica, who received a stay. An account of the divorce and its repercussions is in Ruth L. Middleton, “The Volkert Legacy,” typescript. Volkert Artist File, Florence Griswold Museum, p. 9, 11.

- M.L. Alexander, “Cincinnati,” American Art News, May 23, 1914, p. 7. Reference to Schneider dairy comes from Ruth Volkert Middleton scrapbook of newspaper clippings, quoted in John Fleischman, “The Man who Painted Cows,” Ohio, 7, no. 10 (January 1985), 75, and reprinted, with source given as Bronx Home News, in Mary Leonhard Ran, Edward Charles Volkert, A.N.A., 1871–1935 (Cincinnati: Mary Leonhard Ran Fine Paintings, 1983), p. 3.

- “Human Interest,” The Art Digest, August 1928. The article’s unidentified author explains that Volkert’s remarks came from an anecdote-filled press release received from the Lyme Art Association.

- The remark comes from a review of an exhibition of the work of the “Painter Friends,” including Volkert, at Milch Galleries in New York. Helen Appleton Read, “Many Art Exhibitions; Few Displays Important,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 25, 1917, p. 35.

- After his death, a reporter commented on this late timing for Volkert’s rise to prominence: “Only after he had won several coveted prizes in the East did he become generally known as America’s cattle painter.” “Volkert Exhibition,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 8, 1936.

- See, for example, “Lactaria Volkertii,” Mycologia 7 (1915), p. 165, and plates CLVIII, CLX, CLXIII. Murrill explains Volkert’s work here

- 1920 Federal Census, Bronx Assembly District 6, Bronx, New York; Roll: T625_1139; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 349. Accessed here

- Edward C. Volkert papers, 1890-1951. Reel 1606. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- “Volkert’s Unique ‘Cattle-Logs,’” The Literary Digest, August 3, 1935. p. 24.

- Ruth L. Middleton, “The Volkert Legacy,” typescript. Volkert Artist File, Florence Griswold Museum, p. 28.

- “Famed Artist Dies,” unidentified newspaper clipping, March 4, 1935. Volkert Scrapbook, Private Collection.

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook