Hauling and Harrowing

Health and the Food Supply

- Museum Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 10am to 5pm

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook

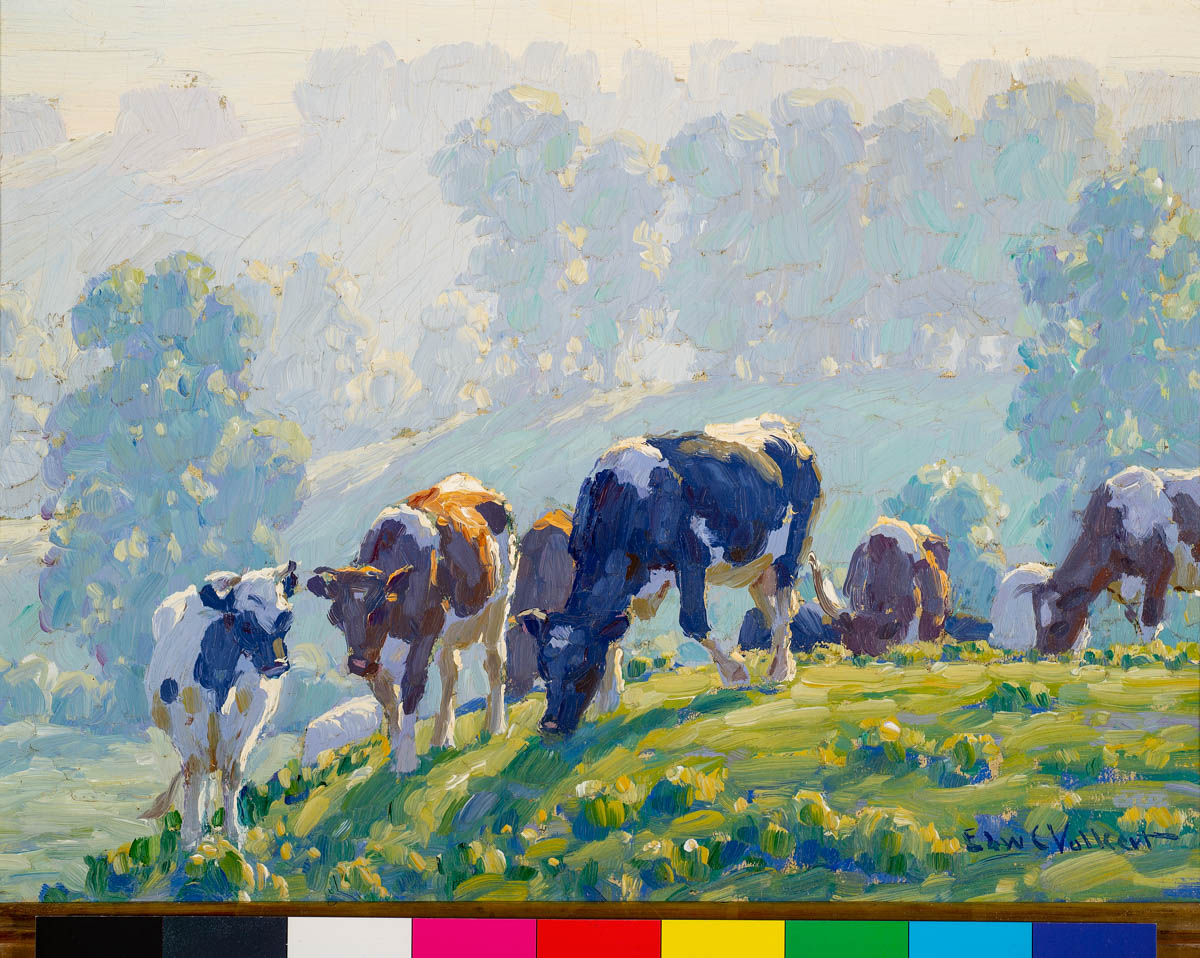

An important context for Edward C. Volkert’s paintings of cows and farms is the transformation of American attitudes and actions toward health and the food supply in the 1910s and 1920s. His depictions of dairy and beef herds present viewers with a glimpse of where their food came from, ones whose idyllic tone suggests the progress made during those years in the handling and quality of foodstuffs.

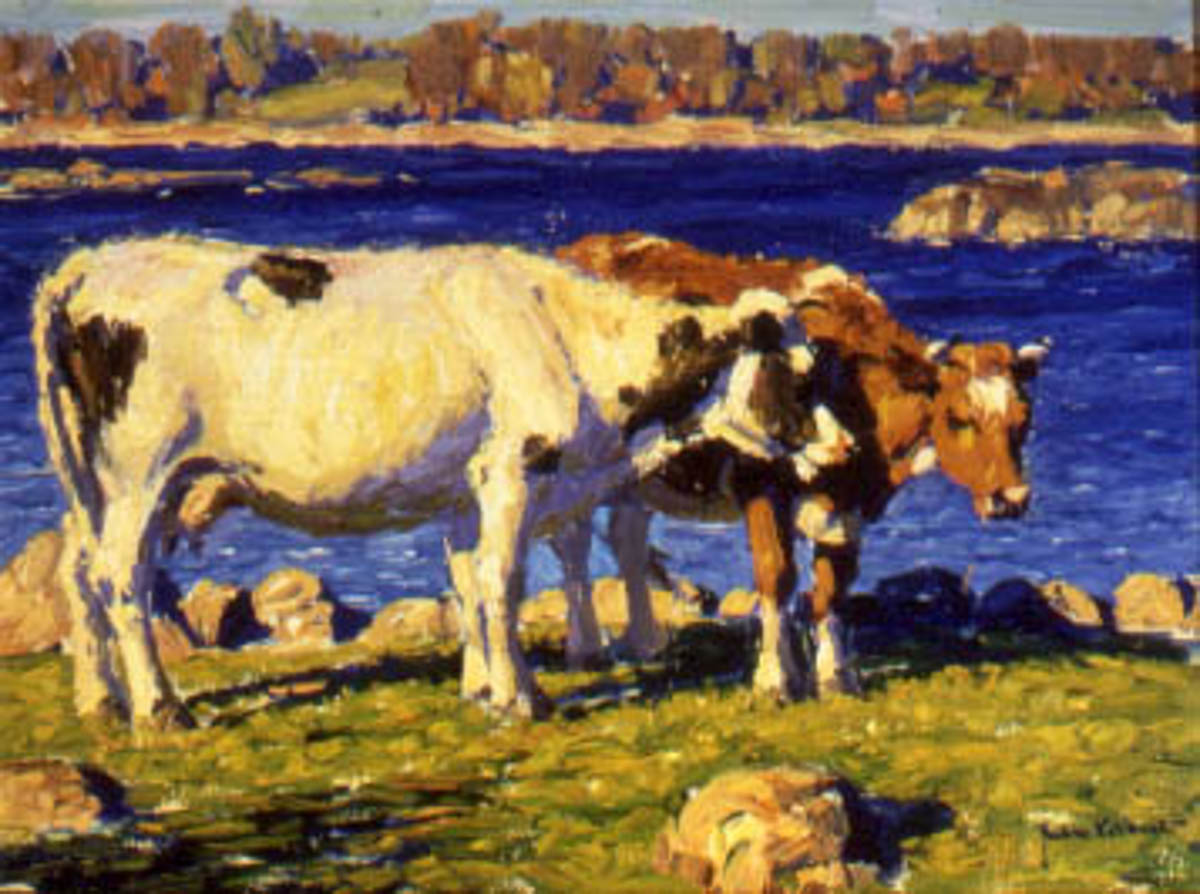

Standing on brilliantly-lit green hillsides or resting in the shade, the hides of Volkert’s bovines gleam, unsullied by their own waste or conditions in the pasture. Critics nearly always commented on the fresh, bright appearance of the animals, equating the prime cattle with the excellence of the painting itself. A generation earlier, artists such as William Henry Howe and Carleton Wiggins emphasized a more homely view of livestock. In their effort to capture both the animals’ appearance and spirit, those painters depicted ruminating cattle with saliva dripping from their muzzles, penned in enclosures, or standing in puddles of gray water. Volkert pulled back from that level of behavioral or environmental detail, and instead injected color and strong contrasts of illumination to merge the cows into mosaic-like patterns of dark and light. His Impressionist treatment of the cattle eliminates the perception of dirt, instead associating the animals with cleanliness and light.

By the 1920s, sanitation had become an American cultural and consumer value, reflected in the popularity of kitchens and food stores outfitted with white enamel appliances, metal surfaces, and linoleum floors for easy cleaning. Awareness of the need for improvements to sanitation in the food supply were prompted in part by exposés of unclean conditions in slaughterhouses such as Upton Sinclair’s 1906 The Jungle. Volkert may have encountered some of these horrors in his own visits to slaughterhouses, where he is said to have studied bovine anatomy for translation to his art.(1) The reforms resulting from Sinclair’s exposé included the passage in 1906 of the Pure Food and Drug Act, which outlawed the production and sale of deleterious or misbranded food or medicine, and the Federal Meat Inspection Act, which prohibited the sale of adulterated or misbranded meat and meat products as food, and required that meat be slaughtered and processed under sanitary conditions.(2) Americans’ perceptions of the food supply’s safety, particularly with respect to meat, increased following the introduction of inspections enforcing these laws.

Public health improved over the course of the 19-teens and 1920s with the shift toward a cleaner food supply. Animal health was recognized as another key component of food safety. In 1917, the first test for bovine tuberculosis—a disease whose transmission to humans caused tremendous suffering—was developed, and infected animals destroyed at a large-scale.(3) As a result of these measures, cattle became less of a risk to humans, perhaps inclining Americans toward greater appreciation of them as subjects in Volkert’s paintings. The optimistic mood of his rural scenes reflects the more benign relationship between people and animals made possible by improvements to the food supply and public health. At the same time, the discovery in these years of vitamins and of the links between diet and physical wellbeing prompted Americans to begin considering food as a source of health, not just sustenance.(4)

While the majority of Americans no longer lived on farms, concerns about potential shortages of food during World War 1 prompted many people to start victory gardens, raise chickens, and take other steps to bolster the availability of provisions. Producing food became a civic good, extending public interest in the sources and quality of nourishment. Volkert’s depictions of farms and farm animals found new appreciation in these years, when they were exhibited around the country. His pictures take viewers back to the source—the verdant pastures where cattle graze at the healthful starting point of their role in generating milk or meat for consumers.

On the other end of the supply chain, most Americans in the 1920s encountered their food in stores, where the enthusiasm for public health shaped buyers’ expectations and experiences. The first grocery chain stores emerged in that decade, offering fresh meat and milk, as well as new inventions such as frozen food, in neat, eye-catching, self-service displays, inside spaces outfitted with white tile and enamel to announce their cleanliness. Advances in the 1920s such as electric refrigerators and freezers helped keep food at safer temperatures, reducing pathogens that could cause illness. With respect to dairy products, in 1924 the Public Health Services laid the foundation for the Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance, which ensures that all milk is sanitized. Bolstered by food safety laws, consumers brought newfound confidence to their grocery purchases that reflected their faith in the wholesome origins of their provisions, all despite the fact that on a daily basis fewer and fewer Americans were in contact with the sources of that food. Volkert’s paintings of cattle herds reminded viewers of those origins.(5)

Footnotes

- Volkert modeled the animals in clay, then cast them in bronze, as sculptures.

- URL https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/informational/aboutfsis/history

- URL https://www.jstor.org/stable/3874818?seq=1

- URL https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/themes/the-nobel-prize-and-the-discovery-of-vitamins-2/

- An anecdote recorded by a Volkert family member indicates that the artist consider one pair of oxen who modeled for him nearly his pets. When he whistled, they came, until one day his whistle went unanswered. “No oxen appeared. To his horror, he discovered they had been sold to the butcher by the farmer who used them, because they had become old and unable to work. What was, to the agrarian mentality, entirely fitting and appropriate as a solution to the reality of age, was so upsetting to Edward that for some time he could not bring himself to paint oxen.” “The Volkert Legacy,” Volkert Family memoir typescript, Artist File, Florence Griswold Museum, p. 33.

Farm Labor | Health & the Food Supply | Rural & Urban Relationships | Technological Change

Home | Biography | Volkert’s Work | Historic Footage | Timeline | Scrapbook