by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured image: Samuel Walters, The Ocean Queen, 1851. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William E.S. Griswold, Jr., in Honor of the Centennial, 1997.3.1

“There is now no doubt but that the clipper ship Ocean Queen, Capt. W. B. Smith, of the New York and London line, has been lost, and 123 persons have perished,” the Boston Pilot reported on July 19, 1856, in its column “Tidings from the Sea.” “She sailed from London on the 8th of February last, with a miscellaneous cargo, 90 passengers, and a crew of 33 persons.” The ship had last been seen on February 15 off the Isle of Wight. Until 1855 Captain Robert H. Griswold (1806–1882), Florence Griswold’s father, had commanded the handsome vessel commissioned by his family’s prosperous New York shipping company in 1850. A portrait of the Ocean Queen is in the collection of the Florence Griswold Museum.

The New York Daily Times had already reported on June 23, 1856, the loss of the Ocean Queen, along with the Driver. “The clipper ship Ocean Queen sailed on the 15th February, from London, and was heard of at Portsmouth on the 17th of the same month, since which time all trace of her has been lost. It is supposed that both vessels encountered the ice, which was then present in the Atlantic in such large bodies, and were foundered or broken in pieces by the violent storms so prevalent during all of last Winter.”

Thomas Coke Ruckle, Captain Robert Harper Griswold, 1840. Watercolor on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Dr. Matthew Griswold, 1973.4.2

The Ocean Queen was described as “about six years old, of 1,200 tons burden, owned by Griswold, Morgan & Co., partially insured.” The ship had sailed from London with a miscellaneous cargo and 90 passengers, including 20 Germans and one infant. Captain W. B. Smith and 32 other crew members were lost at sea, among them the third mate, Henry Comstock (1833–1856) from Old Lyme.

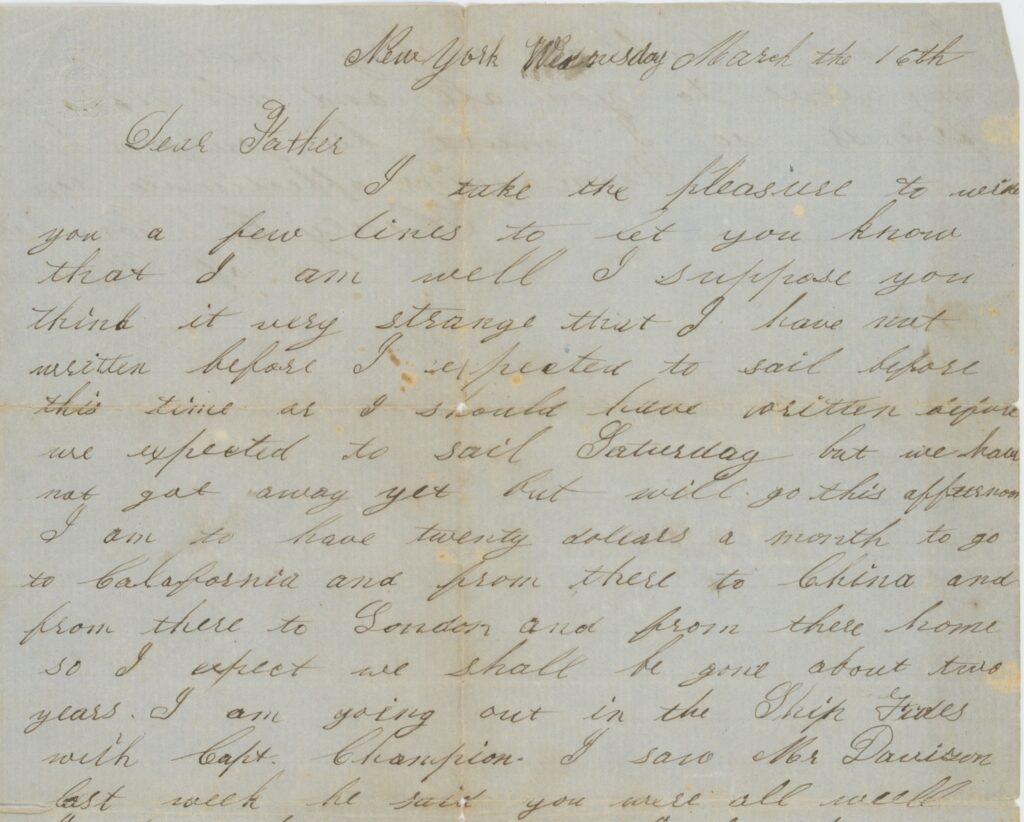

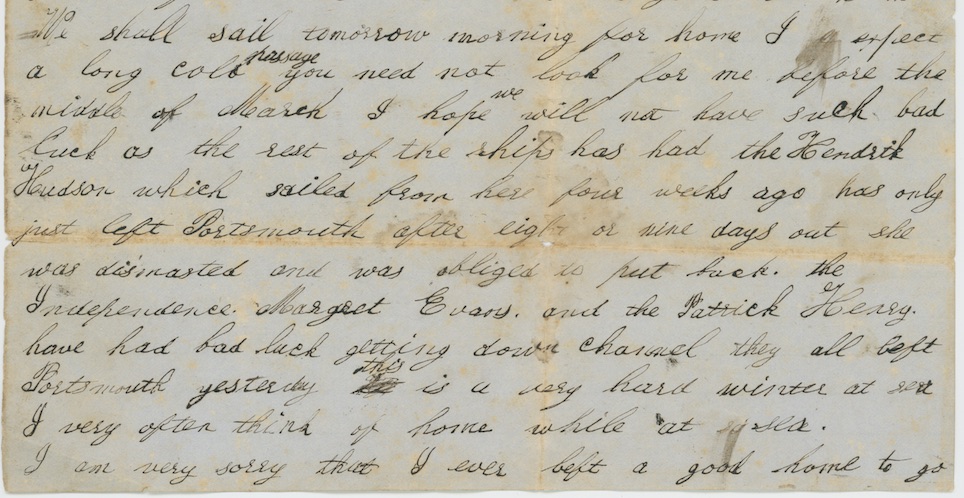

The day before the Ocean Queen sailed, Henry wrote to his father expressing worry about the impending voyage. The letter to Charles Frederick Comstock (1811–1893), my great-great grandfather, related the hardships of the prior crossing. Henry wrote, while sitting on his sea chest, that the passage from New York had been cold and rough, and he had been sick for a week with his face “broke out all over.” Some had feared it was “the small pox,” but no one else had “catch’d it,” and Henry had recovered. “We shall sail tomorrow for home,” he wrote, advising his father not to look for him before the middle of March. “I hope we will not have such bad luck as the rest of the ships has had.”

On the eve of the Ocean Queen’s ill-fated voyage, Henry’s letter documents the volume of commercial shipping traffic in the Atlantic despite the winter crossing’s risks. The Hendrick Hudson, “which sailed from here four weeks ago has only just left Portsmouth after eight or nine days out she was dismasted and was obliged to put back.” The letter also noted that the Independence, Margret Evans, and Patrick Henry all “had bad luck getting down channel they all left Portsmouth yesterday this is a very hard winter at sea.”

Philip John Ouless, The American Packet Ship Patrick Henry off the Cliffs of Dover. Private Collection, Courtesy Bourgeault-Horan Antiquarians

The Griswold family’s New York shipping business offered opportunity to enterprising young men from Old Lyme. Henry Comstock had completed eight years of education offered in the town’s district schools and at age 17, according to the 1850 census, worked as a tailor. He wrote confidently to his father two years later from New York about having signed up for a round-the-world voyage. “I am to have twenty dollars a month to go to California and from there to China and from there to London and from there home, so I expect we shall be gone about two years,” he reported on March 16, 1852. “I am going out in the Ship Fides with Capt. Champion.” Henry anticipated his father’s concerns and sent words of reassurance: “I have been well since I left home it makes me feel bad to think that I am going to be gone so long from home.” In closing he added, “I suppose you will feel bad of my going but you must keep up good cheer for two years will soon pass away.”

No other letters from Henry’s 1852 voyage survive, but maritime records trace the journey of the Fides, a schooner licensed to N. L. & G. Griswold, the New York shipping firm owned by Nathaniel and George Griswold, who grew up on their family’s farm in today’s East Lyme. After the Fides reached San Francisco on September 16, 180 days from New York, it transferred merchandise to the firm of D. L. Lord & Co. On November 24, 29 days from the port of San Francisco, the Fides arrived at Tahiti, carrying oranges and other cargo for someone named E. P. Adams. The ship was seen on January 19, 1853, off the Nantucket Shoals as it neared the end of its crossing from London to New York.

Letter from Henry Comstock to his father, March 16, 1852 (excerpt), Comstock Papers, LHSA

Three years later while waiting for the Ocean Queen to sail from London, Henry’s thoughts about life at sea had changed. At age 23 he no longer offered words of good cheer but warned his father never to allow his younger brother Merritt Comstock (1835–1917) to choose similar work. “I am very sorry that ever I left a good home to go to sea and I hope Merit will never think of going to sea if he does he is very foolish.” Henry said that he had “seen more hardships this winter than I ever did before. I had rather go three voyages in summer than to go one in winter.” He added that he would send Merritt some Valentines, as his father had requested, “but you will not get them in time for Valentine day.” His last words conveyed regret that he had no “time to write any more so I must bid you good bye.”

Letter from Henry Comstock to his father, 1856 (excerpt) , Comstock Papers, LHSA

None of Henry’s brothers went to sea. Merritt Comstock remained in Old Lyme and worked with his father, a master carpenter who built two of the stately houses on today’s main street and another on Academy Lane. Eugene Comstock (1843–1906) found work across the Connecticut River in Essex in a comb store that sold ivory products made from elephant tusks imported from Africa by S. M. Comstock & Co., a cousin’s firm. In 1863 tragedy again struck the family when Henry’s younger brother Charles F. Comstock Jr. (1841–1863), called Fred, died at age 22 in the Civil War, whether from disease or friendly fire is not known. His father, long a deacon in the Baptist church, erected a large monument in Duck River Cemetery that recalls: “Charles F. Comstock, Son of Dea. Charles F. and Eliza Comstock, was killed near Alexandria March 1863 in the service of his country.” The epitaph, today almost illegible, expresses the grief of a father at the loss of a second son:

Not so the good can never die

They just are hid with Christ on high

The victory won, the battle o’er

He dwells with Christ forever more.