By Carolyn Wakeman

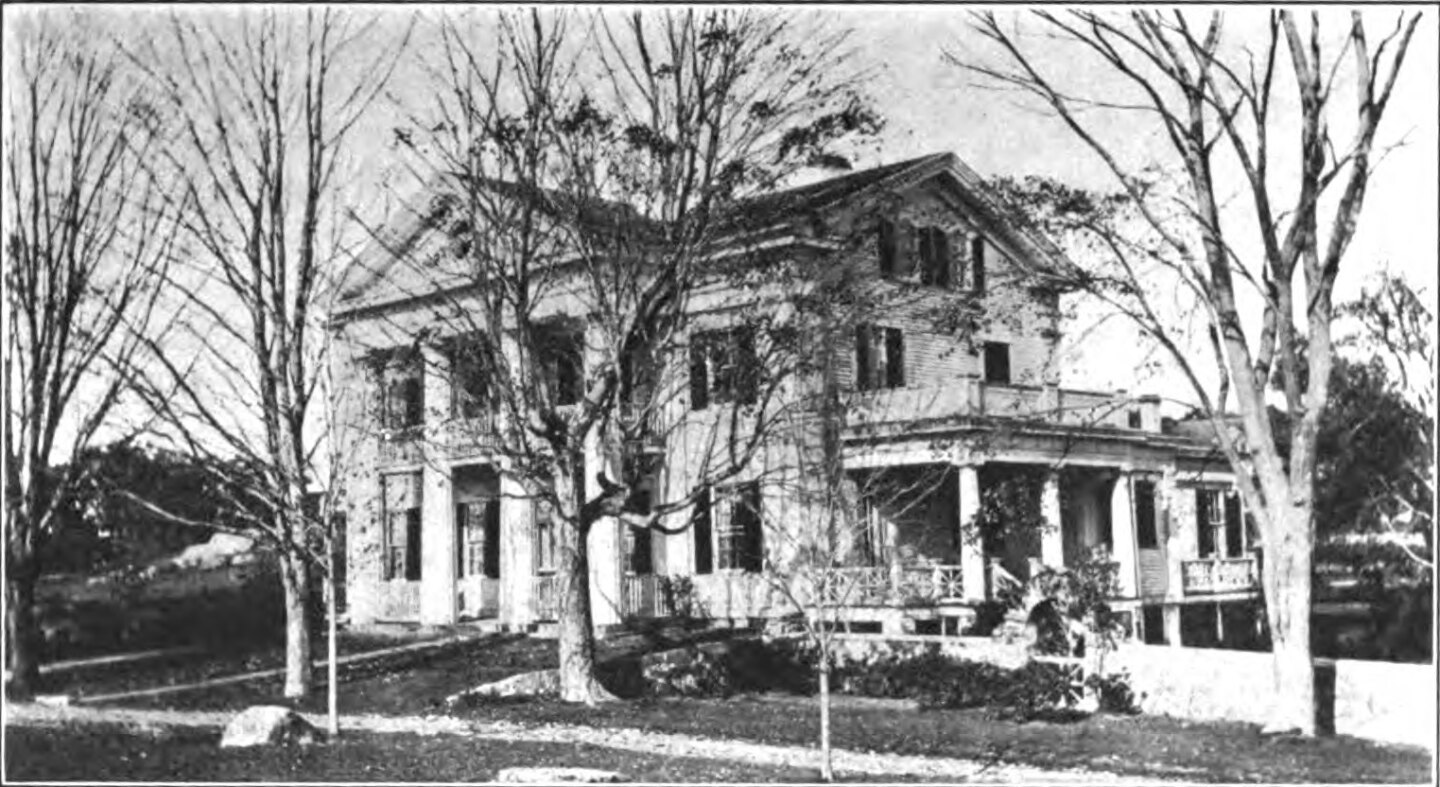

Featured Image: William Lord house, Tantummaheag. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

The story of visionary Albert Einstein’s summer in Old Lyme, with its Princeton connections, links two consecutive exhibitions at the Florence Griswold Museum, Dreams & Memories (October 2022–May 2023) and Object Lessons in American Art: Selections from the Princeton University Art Museum (June 2023–September 2023).

Old Lyme’s scenic location attracted not only artists in the early 20th century but other visionaries and dreamers. Among them was Albert Einstein (1879–1955), who spent the summer of 1935 in an elegant Greek Revival house overlooking the Connecticut River. Einstein had received the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics and after fleeing from Hitler’s Germany accepted a lifetime appointment at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies in 1933. Two years later he rented for the summer a secluded home, known as the White House, in the section of Old Lyme called Tantummaheag. The stately house with its expansive Connecticut River vistas offered the renowned scientist a place to think, to sail, and to dream.

The former Dr. William Lord house remodeled in 1902, showing raised wings and porches. Country Life in America (May 1913).

Dr. William Lord (1753–1862), born in Tantummaheag, practiced medicine in Stonington before building the elaborate white-columned house in 1829 on land originally acquired by his ancestor William Lord (1618–1678) in 1672. After Brooklyn banker James Noel Brown (1850–1917) purchased the house with 20 acres in 1899, his daughter Katharine L. Brown undertook extensive remodeling and redecorating. Her 1902 renovations added new side wings, porches, gardens, and a tennis court to the former Lord estate. An old sheep meadow became a golf course where Princeton University President Woodrow Wilson played during summers spent in Old Lyme with his wife, artist Ellen Axson Wilson.

Margot Einstein, Elsa Einstein, and Helen Dukas at the White House in Old Lyme. from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (N.J.)

A Princeton connection also brought Einstein to Old Lyme. Alice Brown (1874–1947), Katharine’s sister, had married in 1900 Williamson Updike Vreeland (1870–1942), a professor of romance languages at Princeton. Professor Vreeland recommended the house to Einstein as a place to escape from an admiring and sometimes intrusive public. Einstein’s wife Elsa and his secretary Helen Dukas moved with him to the riverside estate in June 1935. Using embossed stationery with the address “Tantummaheag, Old Lyme, Connecticut,” Elsa Einstein wrote in July to their close friend Otto Nathan (1893–1987), an economist teaching at Princeton who had also fled Nazi Germany in 1933: “Everything is so luxurious here that the first ten days—I swear to you—we ate in the pantry. The dining room was too magnificent for us.”

Redecorated dining room in the White House at Tantummaheag. Country Life in America (May 1913).

Elsa Einstein had already described in an earlier letter the solitude that Tantummaheag afforded. “Here at the White House,” she wrote to Dr. Nathan on June 8, “there is peace and quiet, an uncanny stillness. Only on quite out-of-the way paths in high mountain regions does one sometimes experience such deep silence as this.” Two nearby houses would soon be inhabited, she said, so the setting would “probably be less desolate and lonely, but not peaceful anymore, either.” Describing the unfamiliar luxury in which they found themselves, she noted that the house estate offered “a tennis court, a swimming pool, all sorts of summer pleasures that we do not desire and, nevertheless, now have at our disposal.” At Tantummaheag, she wrote, “We are living wonderfully, so elegantly that Albert is embarrassed and until now we have always been dining at the so-called servants’ table in the kitchen.”

Elsa’s letters from Old Lyme reveal other matters weighing on their minds. The Einsteins were urgently assisting Hans Meyer who had fled from Germany and reached Paris, where the American consul was denying permission for him to travel. His man’s passport, she wrote, would soon expire, and they had sent a detailed statement of support emphasizing that they regarded the Hans as their own son, but the consul remained adamant. “Isn’t it a shame and a scandal,” she remarked to Dr. Nathan, “that my husband is not in a position to bring over his nephew on an affidavit and every possible guarantee?” She could find no explanation for the refusal unless the consular official was pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic, or for some reason held “a malevolent attitude toward Albert Einstein.”

Einstein did not entirely escape from view in Old Lyme, and the publication of his latest theory of relativity drew a national reporter to Tantummaheag. An article published in the Detroit Evening News on July 5, 1935, recounts an interview with the famous scientist on the Brown family’s dock, where Einstein had just returned with Elsa after a two-hour sail. On the previous evening they had watched neighbors shooting fireworks to celebrate Independence Day, and the émigré scientist remarked that the holiday had special meaning for him in his newly adopted country. Wearing a white sailor’s cap that partly covered his long gray hair and no shirt, Einstein described his latest understanding of the relativity theory. He also mentioned that he had run aground while sailing on July 4th and had hailed a passing motorboat to tow his small sloop to shore.

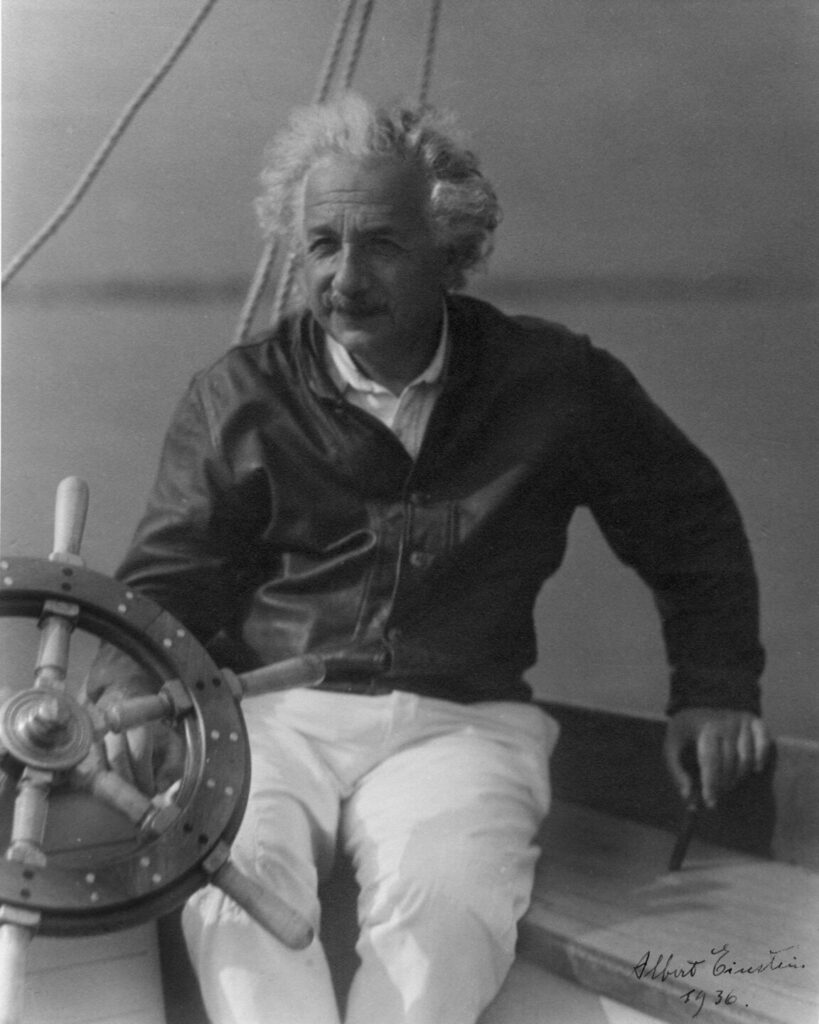

Einstein poses for a photograph while sailing, 1936. Image courtesy of the AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Edgar Edelsack

To pursue his passion for sailing, Einstein had rented an 18-foot Cape Cod Knockabout from the Essex Boat Works, but his distractedness and his unfamiliarity with local sailing conditions brought repeated mishaps. Old Lyme residents would later tell stories about his eccentric appearance when, with his chauffeur, he picked up groceries at the local A & P and mail at the post office, but they remembered particularly his need to be rescued when his boat lodged on a sandbar at low tide. Einstein never learned to drive, nor could he swim, but he relished his excursions on the Connecticut River, when he would think and dream while drifting with the breeze.

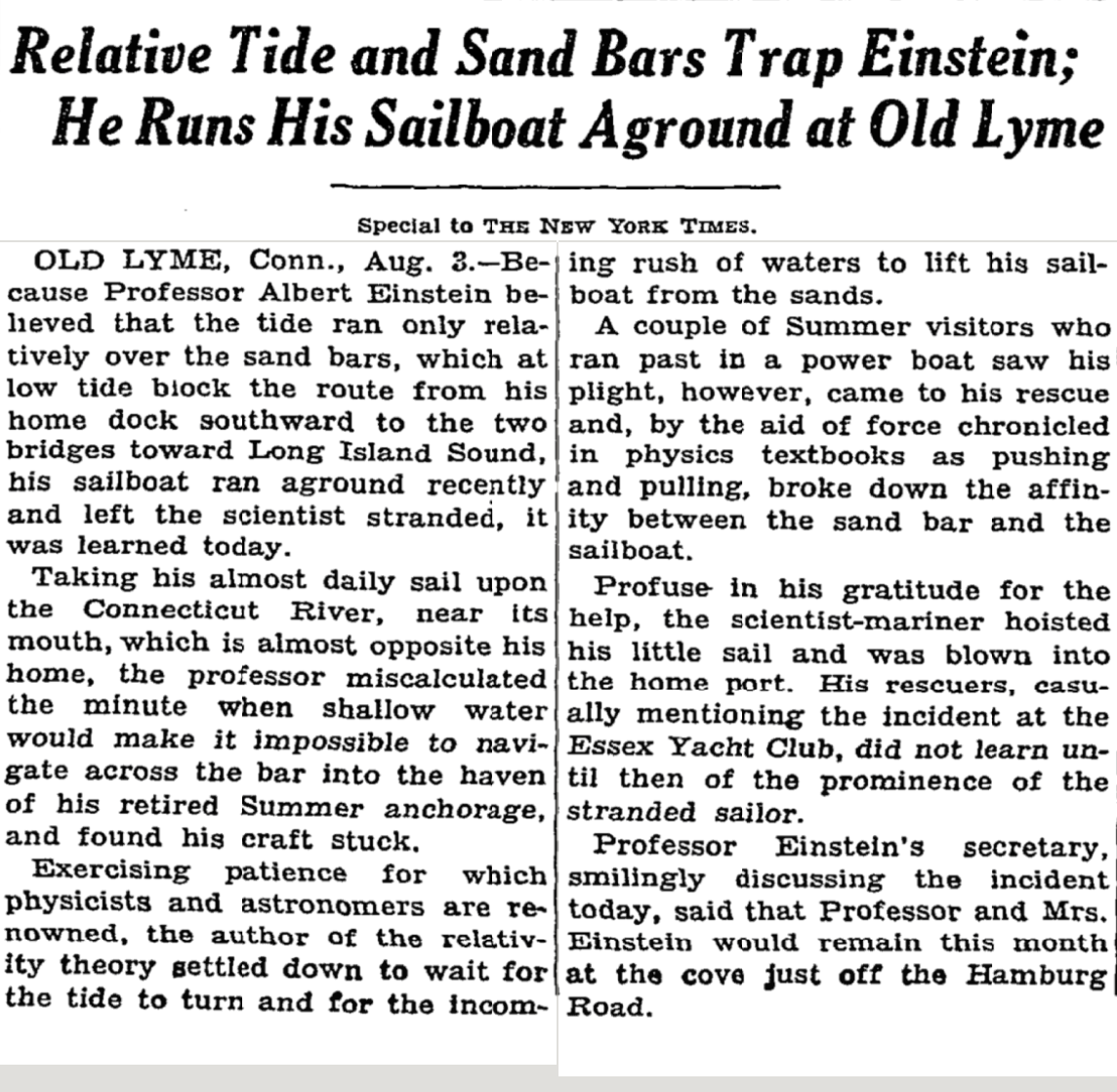

Einstein’s boating adventures drew continuing attention to his summer destination, and one sailing mishap in August prompted a report in The New York Times. “Because Albert Einstein believed that the tide ran only relatively over the sand bars, which at low tide block the route from his home dock southward to the two bridges toward Long Island Sound,” the article notes, “his sailboat ran aground recently and left the scientist stranded, it was learned today.”

The New York Times reported Einstein’s sailing mishap in Old Lyme. The New York Times, August 4, 1935, page 1.

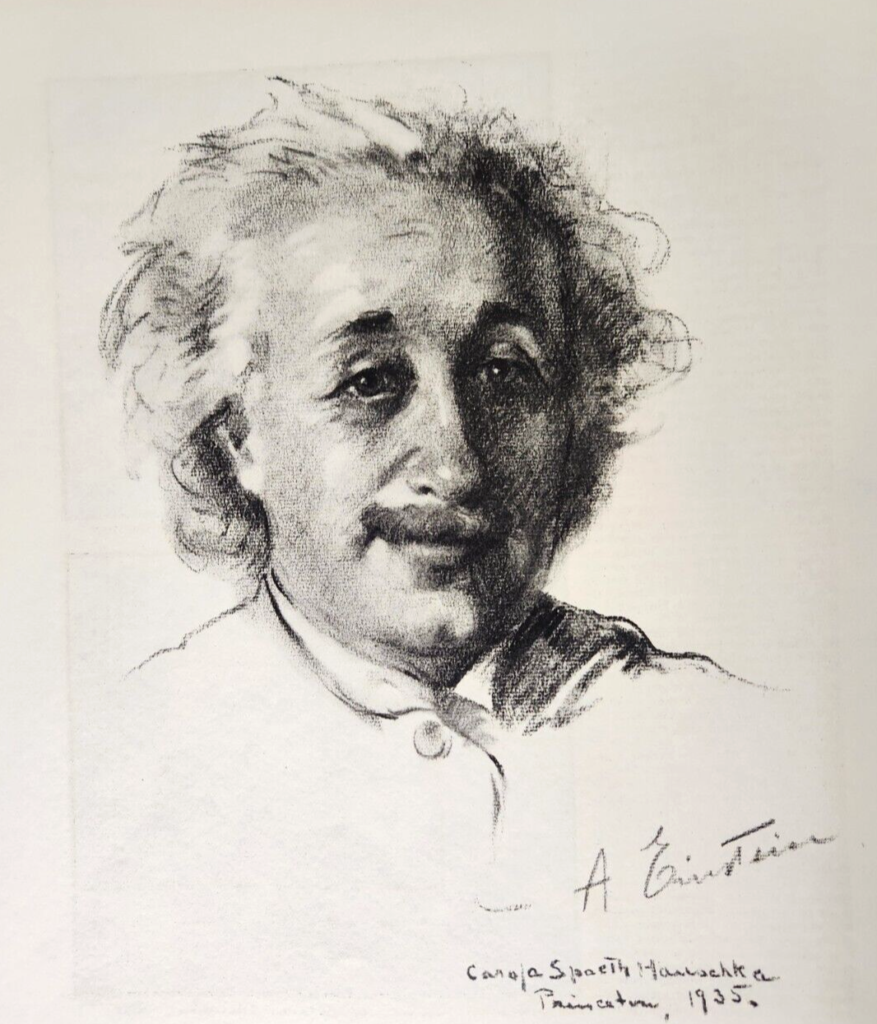

Portrait artist Carola Hauschka Spaeth (1883–1848) also visited the Einsteins in Old Lyme, traveling from Princeton in September to spend a weekend at Tantummaheag. Spaeth shared Einstein’s love of music, which she had studied in Vienna before attending art school in Philadelphia. Whether she produced any of her several charcoal sketches of the Nobel Prize-winning scientist during that summer visit is not known, but a portrait drawn in his Princeton office shows the date 1935.

Carola Hauschka Spaeth, Charcoal drawing of Albert Einstein, Princeton, 1935.

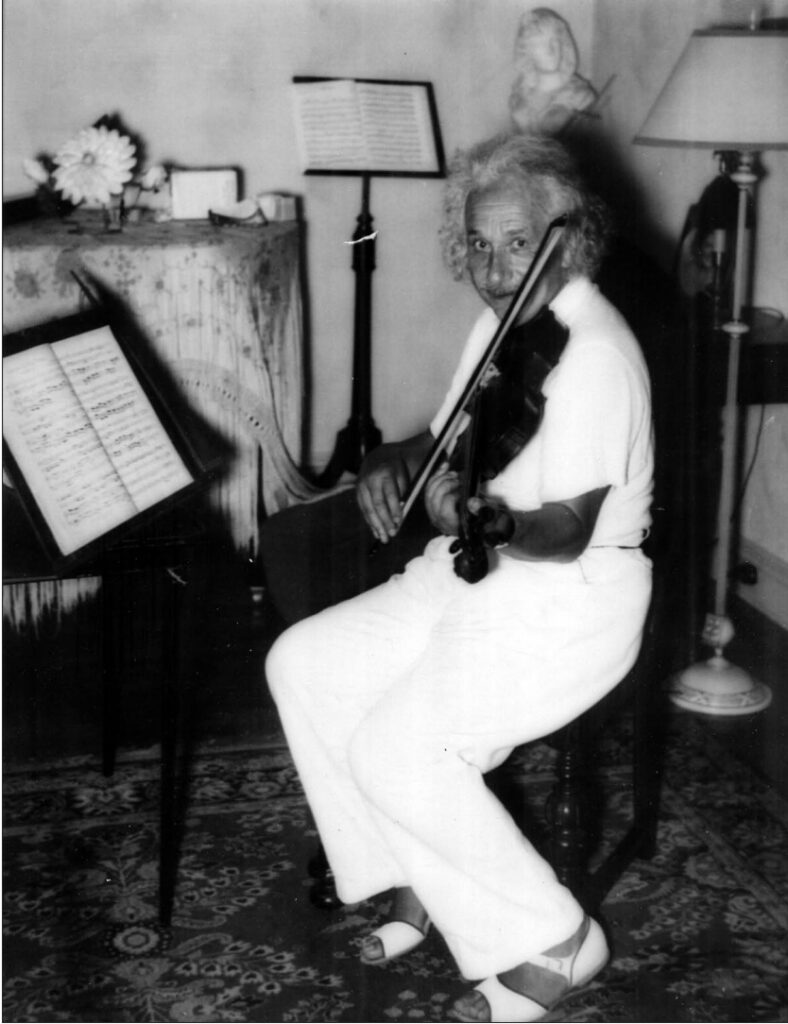

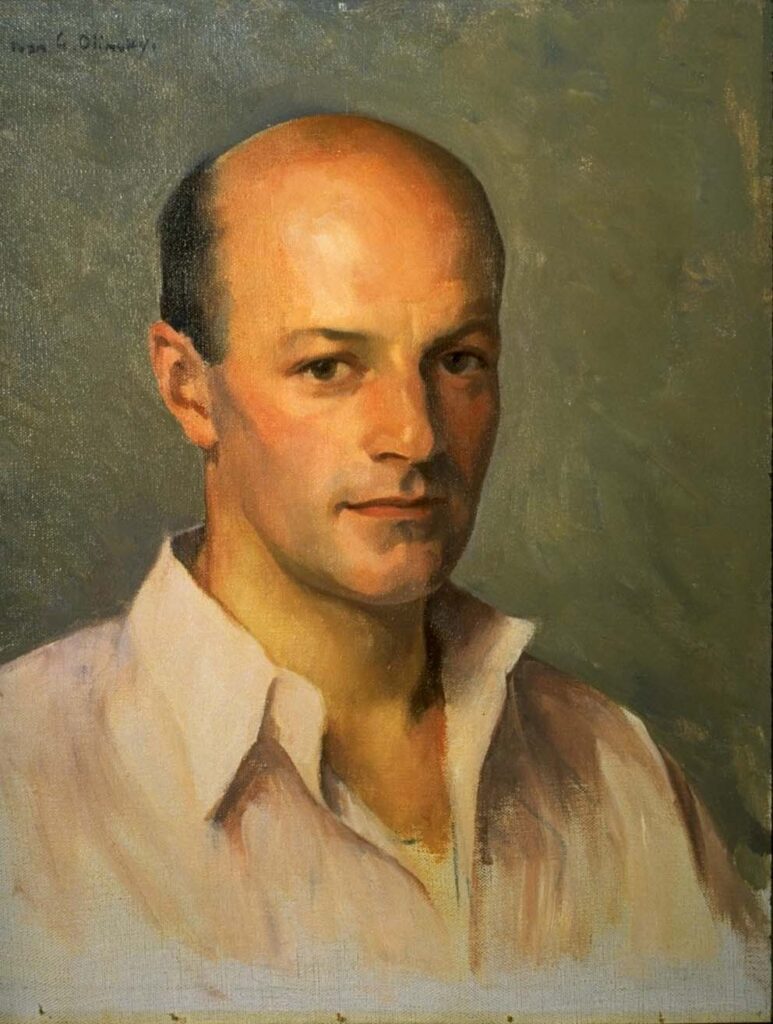

While vacationing at Tantummaheag, Einstein also found frequent opportunities to play the violin. Through the Vreelands he met Mary Dittler, a concert pianist, and her husband Herbert Dittler, conductor of the Columbia University Orchestra and a violin soloist. They invited Einstein to play regularly with them in their summer home on Sill Lane. Old Lyme had become a summer arts destination by 1935, and New York newspapers published glowing columns about the popular exhibitions of impressionist paintings held in the Lyme Art Association’s handsome gallery.

Einstein playing violin. (Photo courtesy of the Southold Historical Society and the Family of Reginald Donahue.)

Whether Einstein viewed the summer oil-painting exhibition is not known, but his friendship with the Dittlers and the Vreelands, who generously supported the Lyme Art Association, connected him with others who contributed actively to the arts in Old Lyme. Among them was Connecticut’s suffrage movement leader Katharine Ludington. The Dittlers had performed in August 1919 in a concert “for the benefit of he Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association,” which Ludington led, according to a report in The Musical Courier. Held in the Conference Room next to Ludington’s garden, the concert “realized a large sum for the cause.”

Ivan Olinsky (1878-1962), Portrait of Herbert Dittler, ca. 1931. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum; Bequest of the Estate of Mrs. Mary E. Copp, 1994.1

Albert Einstein spent only one summer at Tantummaheag, but a telegram a decade later from Katharine Ludington renewed his connection with Old Lyme. Ludington, who trained at New York’s Art Students League and worked professionally as a portrait artist until World War I, had inherited her parents’ gracious home and gardens beside Old Lyme’s Congregational Church. Her ardent suffrage advocacy and leadership of Connecticut’s League of Women Voters led her later in life to champion the cause of international peace. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Einstein established the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists to warn about the dangers associated with nuclear weapons. On May 24, 1946, Ludington sent him a telegram stating her intention to contribute to the work of his committee. In a letter from Old Lyme three days later, she enclosed a donation.

Katharine Ludington in her garden, Old Lyme, 1927. Ludington Family Collection, LHSA at FG Museum

Special thanks to Paul A. Davis and the Historical Society of Princeton, to John Hargraves for translation, and to Amy Kurtz Lansing and John E. Noyes for research contributions and editorial comments. For the Einsteins’ letters and activities and Carola Hauschka Spaeth’s portraits, see the Einstein Digital Collection and the online newspaper database The Papers of Princeton.

Other references:

Katharine L. Brown, “The Remodeling of Tantummaheag,” Country Life in America (May 1913),41-44.

Catalogue of the Thirty-Fourth Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture (Lyme Art Association, 1935).

Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe (NewYork 2007), pp. 435-436.

Musical Courier and Review of Recorded Music (August 21, 1919).

Princeton Herald (September 6, 1935).

“Relative Tide and Sand Bars Trap Einstein,” The NewYork Times (Sunday, August 4, 1935).

John Vigor, “Caution: Genius Aboard,” Cruising World (October 1992).