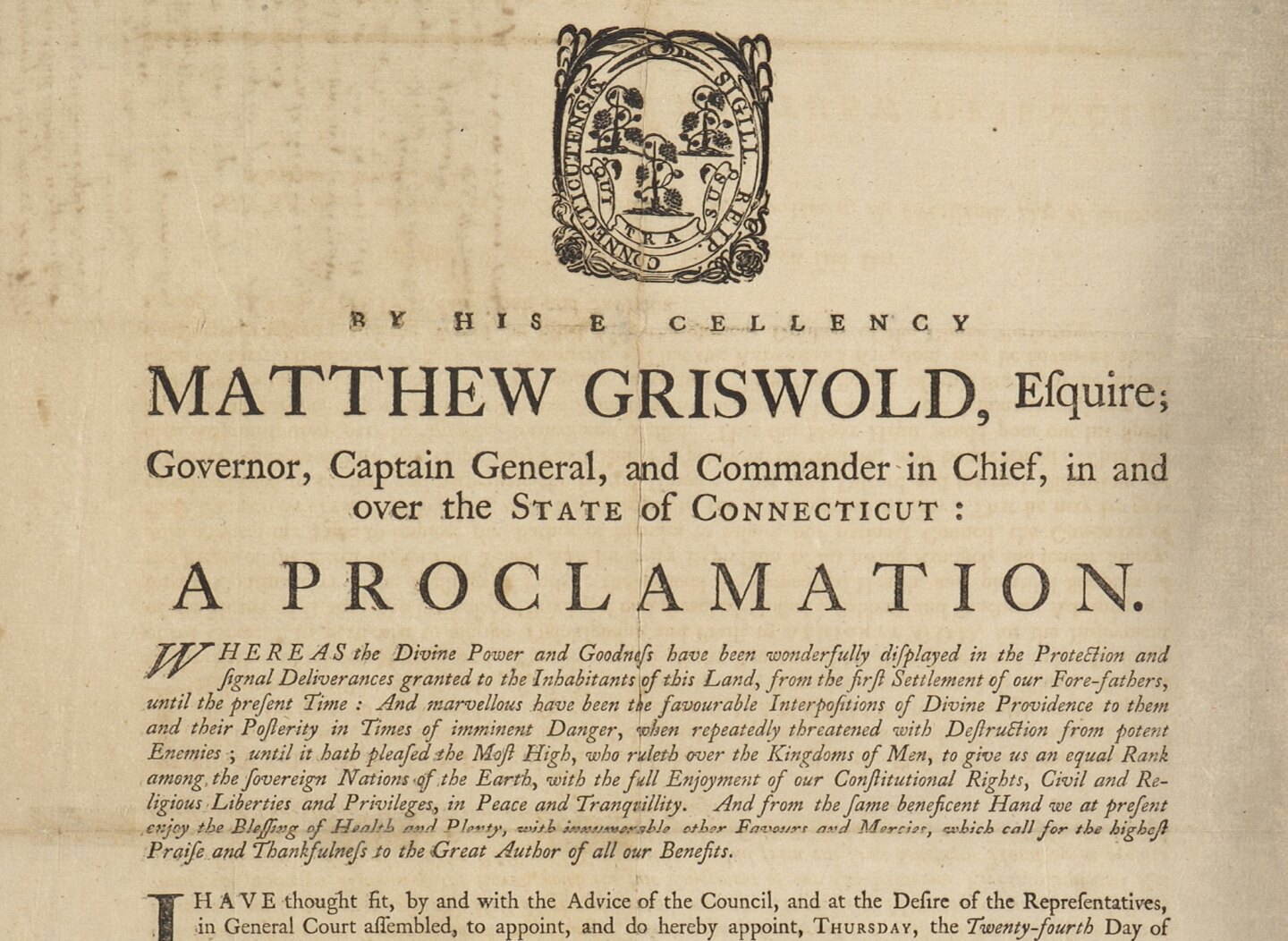

Featured image: Governor Matthew Griswold, Day of Thanksgiving Proclamation, October 1785. Connecticut Historical Society

by Mary Guitar

The Thanksgiving holiday didn’t become a national observance until 1863. However, on October 17, 1785, Governor Matthew Griswold issued his second proclamation naming a Day of Public Thanksgiving throughout the state of Connecticut. He designated Thursday, November 24, 1785, as the date when “People, of all Denominations, with Reverence … present their Thank-offerings to the Father of all our Mercies [including] the Continuation of the Blessings of Peace; the General Enjoyment of Health, and the plentiful Supplies of the Fruits of the Earth in the current Year.”

Matthew Griswold (1714–1799), who was born and lived his whole life in Lyme, served as Governor from 1784 to 1786, beginning his term of office less than a year after the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War. The Constitution of the United States was not written until 1787, not ratified until 1788, and did not begin functioning as the keystone of governance until 1789. When Governor Griswold made his proclamation in 1785, the Articles of Confederation were proving to be inadequate for uniting and governing the new nation in peace time. Connecticut clashed with Pennsylvania over territorial claims in the Wyoming Valley that produced bloody conflict, for example, and the weak federal government could not prevent states from taking actions that risked clashes with other countries. Such concerns certainly must have been on Griswold’s mind when he asked Connecticut’s citizens to “implore the Father of Mercies to inspire our national Council, the Congress of these United States, with Wisdom and Fidelity equal to the Trust reposed in them … [and] to confirm and perpetuate the federal Union that civil Discord and internal Dissension … may be prevented.”

The citizens of Lyme, along with the rest of Connecticut and the other former colonies, were still recovering from the hardships of more than seven years of war: the deaths of fathers, sons, brothers, and friends; the hunger caused by shipping a large portion of locally produced food to those fighting the war; lack of funds for road and bridge maintenance and schools; and lack of investment in mills and manufacturing. The northern section of Lyme was still recovering from a widespread smallpox epidemic in 1776 that left many businesses shut down and houses empty.

Yet, by the mid-1780s, the tide seemed to be turning toward recovery. The “Great Bridge” over the Lieutenant River, built in 1732 but in disrepair, had been widened and rebuilt. Below the bridge Samuel Hill (1745–1818) was building coastal sailing vessels, one of them a schooner named Peggy, the first of 15 vessels commissioned locally for Samuel Mather, Jr. (1745–1809) in the following 25 years. Mather was also building a house on Lyme Street, which would, much later, become the Congregational Church parsonage. Both house and schooner were finished in 1784.

Parsons Tavern. Lyme merchant Daniel Rogers Noyes (1795–1877) purchased Parsons Tavern in the 1830s after construction of the town’s stately new meetinghouse. Noyes built a gabled front addition to the tavern’s rear ballroom, which Marshfield Parsons had added when he converted the parsonage of his father Rev. Jonathan Parsons (1705–1776) to a coaching inn. Photo, ca. 1890. Lyme Historical Society Archive, Florence Griswold Museum

Standing on the town green at the south end of Lyme Street in 1785, where townsfolk had staged a version of the Boston Tea Party in 1774 and mustered troops for the Revolutionary War, an observer from the present day would see some familiar houses as well as some notable gaps. Lyme’s stately white Congregational Church would be built three decades later in a field north of Parsons Tavern, and Rev. Stephen Johnson (1724–1786), nearing the end of his life, would have preached a lengthy Thanksgiving sermon in the Third Meetinghouse located on today’s Johnnycake Hill. Revolutionary activists exchanged political news at Col. Marshfield Parsons’s (1733–1813) tavern, where passengers traveling by stage between New York and Boston stopped for rest and refreshment.

The house of wealthy merchant John McCurdy (1724–1785) stood across from the town green, and just north of it stood Samuel Mather, Jr.’s large new house. Enslaved African Americans continued to serve as domestic and agricultural laborers in the Parsons, McCurdy, and Mather households. The elegant house that New York shipping merchant Richard Sill Griswold (1809–1849) would construct, later called Boxwood, would not be built until 1842.

Peck Tavern postcard, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

At the north end of today’s Lyme Street, above the triangle where Boston Post Road and Sill Lane meet—known in 1784 as Noyestown Green—John McCurdy, until his death the next year, ran a store on the premises of Peck’s Tavern, built on the site of an earlier dwelling in 1769, where travelers gathered and revolutionary soldiers had collected provisions. Above the tavern along Mill Brook, the grist mill and cloth fulling mill had recently closed, but a clothier’s store continued in business. Farther north, off today’s Sill Lane, the Hall family’s ironworks and a nearby blacksmith’s shop produced cooking pans, hardware, and maritime fittings to supply Lyme’s increasingly active shipyards. As coastal trade resumed and farm production increased after the war, the townsfolk of Lyme were likely feeling the energy of a new era and a new country when they commemorated in 1785 Governor Griswold’s “day of public Thanksgiving.”

———

REFERENCES

Kathryn Burton, Old Lyme, Lyme, and Hadlyme (Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2003).

Susan Hollingsworth Ely and Margaret Wellington Parsons, The Parsonage (Old Lyme, 1983).

Susan Hollingsworth Ely and Elisabeth B. Plimpton, The Lieutenant River (Lyme Historical Society Publication, Old Lyme 1991).

James Ely Harding, Lyme as it Was and Is (American Revolution Bicentennial Committee, Lyme, 1975).

Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Wesleyan University Press, 2019).