By Patty Devoe

Featured Image: Tea Caddy, c.1790, porcelain, Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of the Old Lyme-Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library, from the Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury Ceramics Collection, 1959.248 a&b.

The Florence Griswold Museum’s fall 2023 exhibition Oceangoing: Art and Archival Collections about Lyme’s Links to the Sea features a vibrantly decorated tea caddy from the ceramics collection assembled by Old Lyme philanthropist and antiquarian Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823-1917). In its original state the Salisbury collection included over six hundred pieces and offers a rare example of late 19th century “china hunting.”[1] These were not complete sets but rather the remaining evidence of hearth and home of early families in New England, especially those of Lyme and Old Lyme. The items Salisbury assembled showcased the social status of her family, but they also embodied the spirit of patriotism and civic pride that motivated “china hunters,” who were generally wealthy, elite, influential women who traced their ancestry back to colonial families. These collectors took it upon themselves to preserve America’s history through the story of china, with each piece purposely chosen. Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, who privately published in 1892 with her husband Edward E. Salisbury (1814-1901) a laudatory five-volume record of her extended family’s history, was a grande dame of the Connecticut china hunters.

Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury. Photograph. Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 8, #9. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury. Photograph. Noyes-Ely Family Collection, Box 8, #9. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

McCurdy family home, attributed to Charles Parsons, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume LII, December 1875-May 1876, pg 320. After her marriage to Yale faculty member Edward Salisbury in 1872, Evelyn McCurdy moved to his New Haven residence but returned often to her native Old Lyme and her family’s ancestral home.

Highlights from Salisbury’s collection include three “Nankin” Chinese plates manufactured between 1578-1619 in the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen. The delicate bamboo trademarks on the undersides of these plates are key to their identification. The designation “Nankin” ultimately identified an entire category of ceramics created at Jingdezhen, whose imperial furnaces produced Chinese porcelain for centuries. By 1800 many Western European countries were trading in fancy export chinaware to satisfy eager consumers back home. The Nankin plates in Salisbury’s collection establish a direct link to the early trade between China and the West. Over thirty million porcelain pieces were imported by the English East India Company in the 17th century alone. Other pieces in Salisbury’s collection recall America’s English and Dutch heritage, including a delftware charger with a portrait of King William of Orange that dates from 1690-1700, and a Dutch delft jug that dates to 1710, which Salisbury acquired from the Ely family in Lyme.

Plate, ca. 1730, earthenware, Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of the Old Lyme-Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library from the Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury Ceramics Collection, P1974.3

Old Lyme resident John Alden Lloyd Hyde (1902-1981), a noted antiques dealer and ceramics expert, evaluated the Salisbury collection in 1974. His inventory describes some of its most distinctive pieces with notations such as, “choice early Chinese plate elaborately decorated in beautiful enameled colors from the Diodati family (FGM 1959.245), and “very scarce” tortoise shell plate in the Whieldon-style mottled green and brown decoration dating from about 1770 (FGM 1959.145). Other experts weighed in on the value of the collection, estimating a total value of $25,000-$35,000 in 1976. They considered the desirability and valuation of individual items, but for Salisbury the worth of a piece was significantly enhanced by the prominence of its original owner.

Plate, ca. 1830, porcelain, Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of the Phoebe Griffin Noyes-Old Lyme Library, from the Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury Ceramics Collection, 1959.245

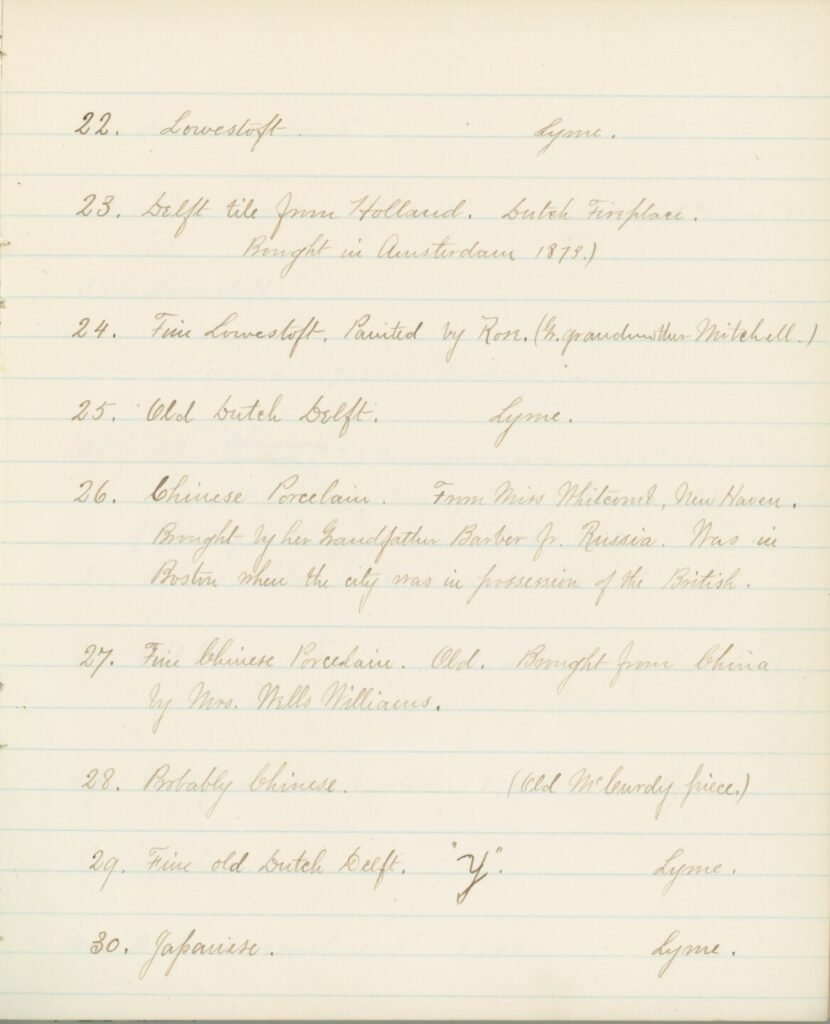

A black leather-bound notebook that provides an earlier, partial inventory of Salisbury’s collection, with details that she included, lists more than a hundred items that originated with relatives or early families in Lyme and Old Lyme. It identifies pieces that belonged to ”My Mother,” to “Aunt Johnson,” and to “Aunt Stewart.” One notation describes the “Fine old Nankin plate” that was “Sent by Mrs. Elizabeth Diodati Scarlett to her grandnieces, daughters of Reverend Stephen Johnson of Lyme between 1744 and her death in 1768.”[2] Another “old Chinese plate” was sent from the Diodati Villa near Geneva, Switzerland, by Salisbury’s Diodati relatives.

Page from Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury’s handwritten ledger.

The earlier inventory also lists multiple pieces connected to Connecticut families who engaged in or profited from mercantile trade with China, such as an “iron red Chinese rice bowl,” dated between 1800-1825, that was “brought to Lyme by sailors who went to China in ships.” An octagonal plate of Chinese export ware decorated with a banana tree, flowers, insects, and the sacred bull of India was “brought by privateers to an early New London family during the Revolutionary War.” Chinese porcelain bowls made during the reign of Yungching (about 1722) were attributed to Samuel Wells Williams (1812-1884), a Chinese missionary who went with Commodore Perry to open trade relations with Japan in 1853. Williams later taught Chinese language at Yale University, where he was a colleague of Salisbury’s husband Edward E. Salisbury. Another “very old” Chinese plate came from the home of Connecticut’s Revolutionary War governor Jonathan Trumbull. Plate Number 50 in this inventory is described as a porcelain piece “out of which Washington drank.

Creamer said to have been used by George Washington. , porcelain, ca. 1775-1790. Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of the Old Lyme-Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library from the Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury Ceramics Collection, 1978.48.

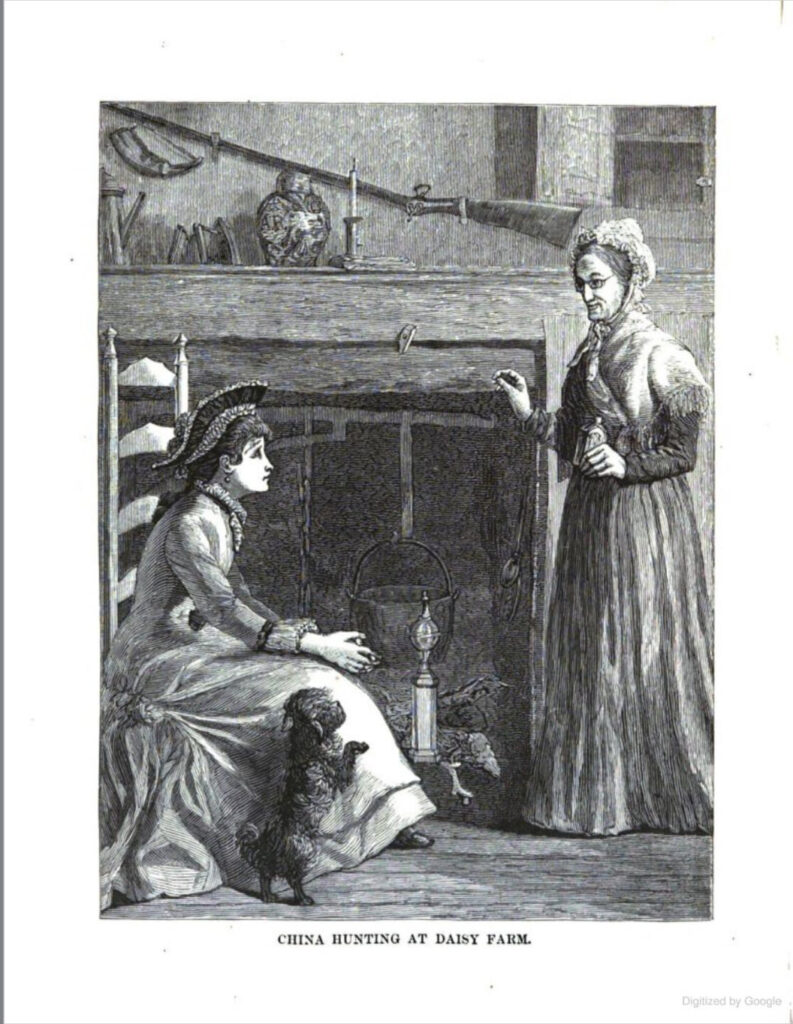

Like other china hunters, Salisbury considered collecting ceramic pieces as a way of conserving America’s rich legacy. Other women literally travelled the countryside “hunting” for desirable pieces to add to their collections. Guiding their efforts were two widely popular books, The China Hunters Club by Annie Trumbull Slosson (1878) and China Collecting in America by Alice Morse Earle (1898). Both authors, Slosson from Hartford and Earle from Worcester, became local celebrities, and their books illustrated choice pieces to collect, gave detailed histories of different types of ceramics, and glorified the efforts of china hunters. For them, saving these antique relics equated to saving America’s history. As Slosson wrote, “the old china and crockery of our own country was a sort of index to the history of families and their way of living; and the history of families makes up the history of a country like ours.”[3] Earle emphasized the idea that “searching for old farmhouses that might contain some salvages of teacups or teapots” was a way of preserving America’s past.[4] Even collecting worn out and damaged ceramics saved them from being lost or used ingloriously, and Earle expressed indignation to see “mugs and pitchers battered, nicked and handleless despitefully being used to hold … toothbrushes or a Washington pitcher… being used to carry hot water to the henhouse.” China collecting was a patriotic act, and gathering collectibles ensured they were being rescued from “the hands of ignorant country residents and preserved.”[5]

“China Hunting at Daisy Farm.” Illustration from Annie Trumbull Slosson, China Hunter’s Club (1878)

These two books served as foundational guides of the Colonial Revival movement, and in 1901, almost thirty years after its publication, booksellers were still seeking copies of Slosson’s The China Hunter’s Club to satisfy consumers.[6]

Newspapers had published details on china collecting, and there were women’s clubs dedicated to the task. A year before Slosson’s book appeared, the Hartford Daily Times published in 1877 an account of the local china collecting craze: “Here in Hartford . . . the China Craze . . . has spread very rapidly during the past year . . . . It would be hard to say how many collections there are now in this city of quaint and rare porcelain, crockery and similar oddities which have a fancy value . . . . Collectors of these articles scour the country round in search of new discoveries and there is scarcely a substantial old farm-house left, in this part of Connecticut, that has not been raided and cleaned out of its hereditary and traditional heirlooms.”[7]

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat devoted almost a full page to china collecting on August 12, 1892.

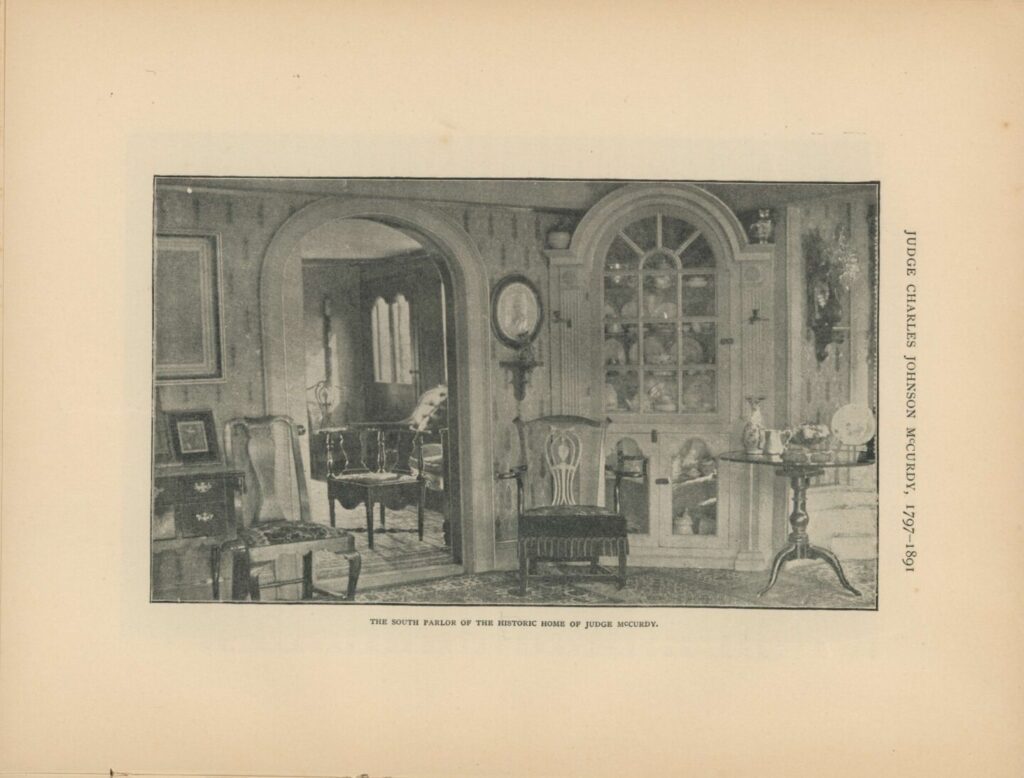

The Hartford Courant had praised Salisbury’s collection in 1876 in an extended review of Old Lyme’s exhibition to celebrate the nation’s centennial. “The artistic and decorated pottery was the most notable feature of the occasion,” the columnist noted. “The collection of rare and beautiful porcelain from the McCurdy family filled a large case and several tables . . . each specimen had some historical, antique, or artistic merit. Some large India platters were from the dinner service of John McCurdy prior to the Revolution and were in use when that gentleman entertained Lafayette and his officers.”[8] Salisbury’s friend Martha J. Lamb (1826-1893), a prominent historian and editor of the Magazine of American History, also noted the collection in The Homes of America (1879)[9] Among other furnishings in the historic McCurdy house in Old Lyme, Lamb described “a curious buffet, built with the house which is appropriately devoted to a choice collection of specimens of China from ancestral families — the Wolcotts, Griswolds, Digbys, Willoughbys, Ogdens, Pitkins, Mitchells, Diodatis and others.” Lamb observed that the collection was “rich with historical interest.”[10]

The south parlor of the historic home of Judge Charles Johnson McCurdy, from In Memory of Judge Charles Johnson McCurdy, 1891, McCurdy Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

After Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury’s death in 1917, her china collection was initially moved from her residences in Old Lyme and New Haven to Old Lyme’s Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library. Her will had specified Yale University, the New Haven Colony Historical Society, or the Wadsworth Atheneum as repositories, but ultimately it was the local library that agreed to house the collection, in accordance with her wishes to display it “and offer the best facilities for installation and preservation of the same.”[11] Included with the collection were the display cabinets she had ordered from Ernest Greene (1864-1936), a New York architect who designed Old Lyme’s library in 1898 and later a replica of the town’s stately Congregational Church, destroyed by fire in 1907. In time, however, the library’s staff expressed “care and concern” that Salisbury’s china collection “may become an expense and a burden which will hinder the Library’s primary function of providing the best possible library materials and services to the Old Lyme community.”[12]

By May 1959 the collection and its custom-built display cases were loaned to the recently established Lyme Historical Society and moved to its location at the Florence Griswold Museum. Formal and legal ownership was assigned to the Museum in the 1970’s. With experts like John Alden Lloyd Hyde, who critiqued and evaluated the overall collection, noting the “wretched condition” of some items, the Museum decided to deaccession pieces considered excessively damaged or unrelated to the typical use and practice of New England households. Some pieces were given back to the Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library, and in 1995 approximately one hundred pieces were sold at auction by Winter Associates of Plainville, Connecticut. The auction yielded $2400. Despite the effort to remove heavily damaged pieces from the collection, bowls held together by staples and other evidence of nicks and cracks remain. After all, the mission of china hunters was to save and preserve the tangible evidence of early American history.

Unfortunately the inventory numbers that Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury assigned in her notebook have not survived, and many of the individual pieces owned by her family members can no longer be identified. Which of the three Nankin plates in the collection was gifted by the Swiss Diodati family to the grandnieces? Where is the red rice bowl brought back from China by an Old Lyme mariner? But despite these uncertainties, Salisbury’s collection remains impressive for its sheer size, the depth of its references to prominent families in Old Lyme and elsewhere in Connecticut, and its unique representation of the “china hunters craze” in the 19th century.

Special thanks to Jane Ludington

[1] The other prominent collections are the Prime Collection at Princeton, the Ann Allen Alves Collection at the Rhode Island School of Design and the Trumbull-Lyons pieces at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

[2] FGM Object File, Bound Black Leather Book, entry number 35.

[3]Slosson, Annie Trumbull; The China Hunter’s Club; Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1878, page 254.

[4] Earle, Alice Morse; China Collecting in America; Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1892, page 3,

[5] J. Semaine Lockwood, “Shopping for the Nation: Women’s China Collecting in Late 19th Century New England”, The New England Quarterly, vol. 81, No. 1, March 2008, pp. 63-80.

[6] Boston Evening Transcript, 2 February 1901, page 18.

[7] The Hartford Daily Times, October 17, 1877.

[8] Hartford Courant, September 13, 1876, page 4.

[9] Martha J. Lamb, ed.; The Homes of America; Appleton & Company; New York, 1879, page 53.

[10] Martha J. Lamb, ed.; The Homes of America; Appleton & Company; New York, 1879, page 53.

[11] Article Fourth, Evelyn MacCurdy Salisbury Will, Probate Estate Files, 1881-1915; Connecticut State Library (Hartford, Connecticut); Probate Place: Hartford, Connecticut, available at ancestry.com

[12] Letter from D.E. Rhein (Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library) to Mrs. Stewart (Lyme Historical Society), August 28, 1976, Object File FGM