The exhibition Impressionism 150: From Paris to Connecticut and Beyond marks the anniversary of Impressionism’s debut and its development from a radical style to an enduring means of expressing the modern sensibility. Artist Matilda Browne is represented in the show by paintings that attest to her ambition, a spirit preserved in her scrapbook–a recent addition to the Museum’s Lyme Historical Society Archives.

by Mary Guitar and Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: Matilda Browne, Blossoming Flowers on River’s Edge, ca. 1907. Oil on wood. FloGris Museum, Purchase, 2023.1

Details about the Lyme Art Colony’s most distinguished painters sometimes appear unexpectedly. Matilda Browne’s scrapbook, purchased by the Florence Griswold Museum in 2021, includes clippings, sketches, letters, photographs, and memorabilia that shed important light on Browne’s artistic career between 1883 and 1910. The bulging scrapbook, its binding frayed from frequent use, passed to her sister after her death. The remarkable collection of items that Browne saved was discovered by chance at a house sale in Cleveland, where the artist’s sister Mary Cummings Browne Hatch (1861–1939) lived.

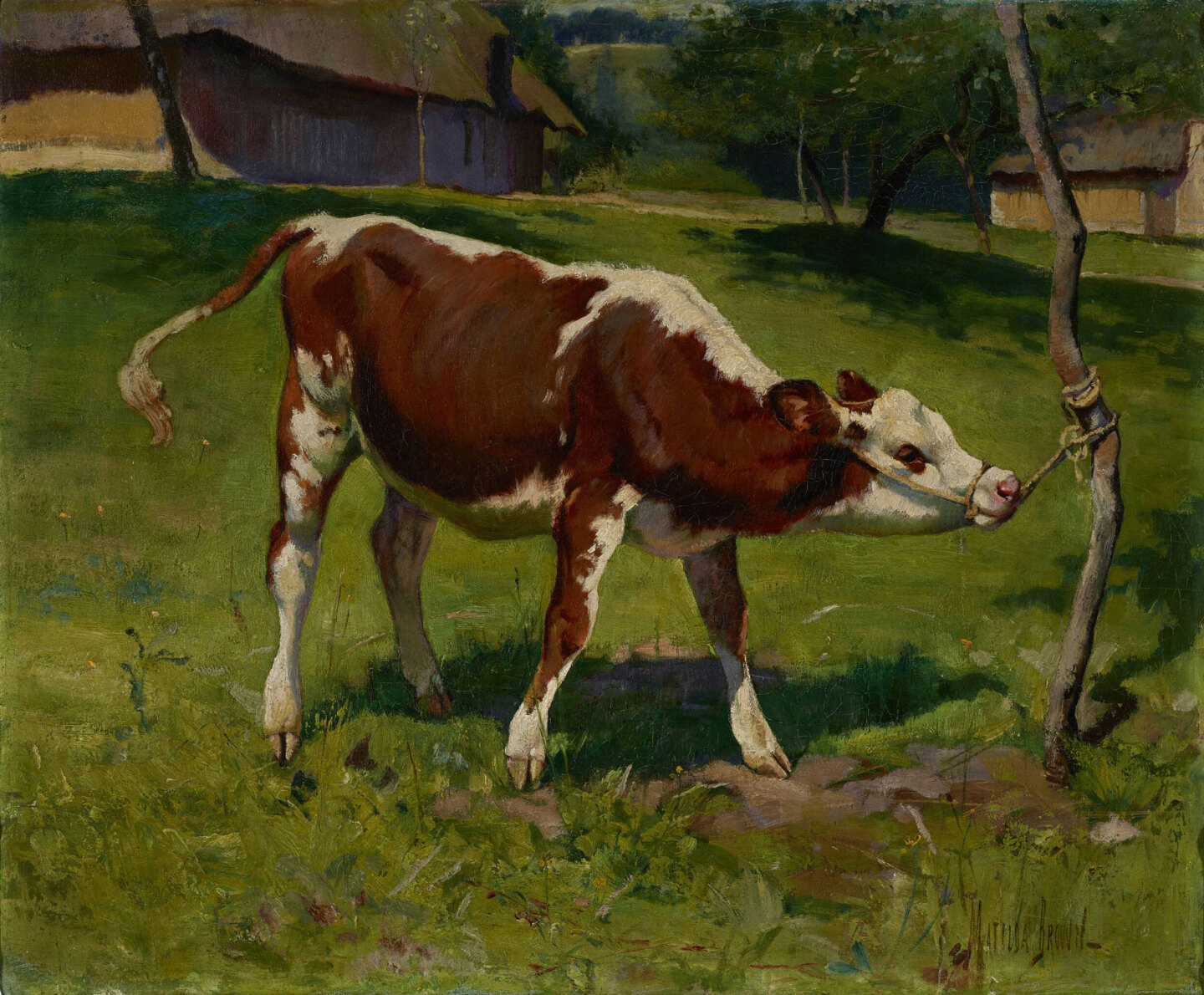

Matilda Browne (1869–1947) began her artistic training at an early age and exhibited at the National Academy of Design when she was fourteen. After travels in Europe, study with artists in Paris and Holland, and exhibition at the Paris Salon, she received increasingly favorable reviews. Her painting An Unwilling Model, which was completed in Holland, depicts a calf straining against its rope. It received an honorable mention at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Matilda Browne, An Unwilling Model, ca. 1892. Oil on canvas. FloGris Museum, Purchase, Dorothy Clark Archibald Acquisition Fund, 2023.12

Browne exhibited widely after settling with her family in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1897. There she met artist Clark Voorhees, an acquaintance who likely prompted her first visit to Old Lyme in 1905. Accepted by the male artists who founded the Lyme Art Colony, Browne was the only woman invited to paint a door panel in Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse. After her marriage in 1917, Browne purchased a house on Lyme Street where she spent summers for six years before returning to Greenwich.

Matilda Browne, Bucolic Landscape, 1905. Oil on wood. FloGris Museum, Gift of the Artist, 1941.9

Matilda Browne’s home in Old Lyme. Browne, Untitled [Yellow house with yellow roses], after 1918. Oil on wood. Private Collection

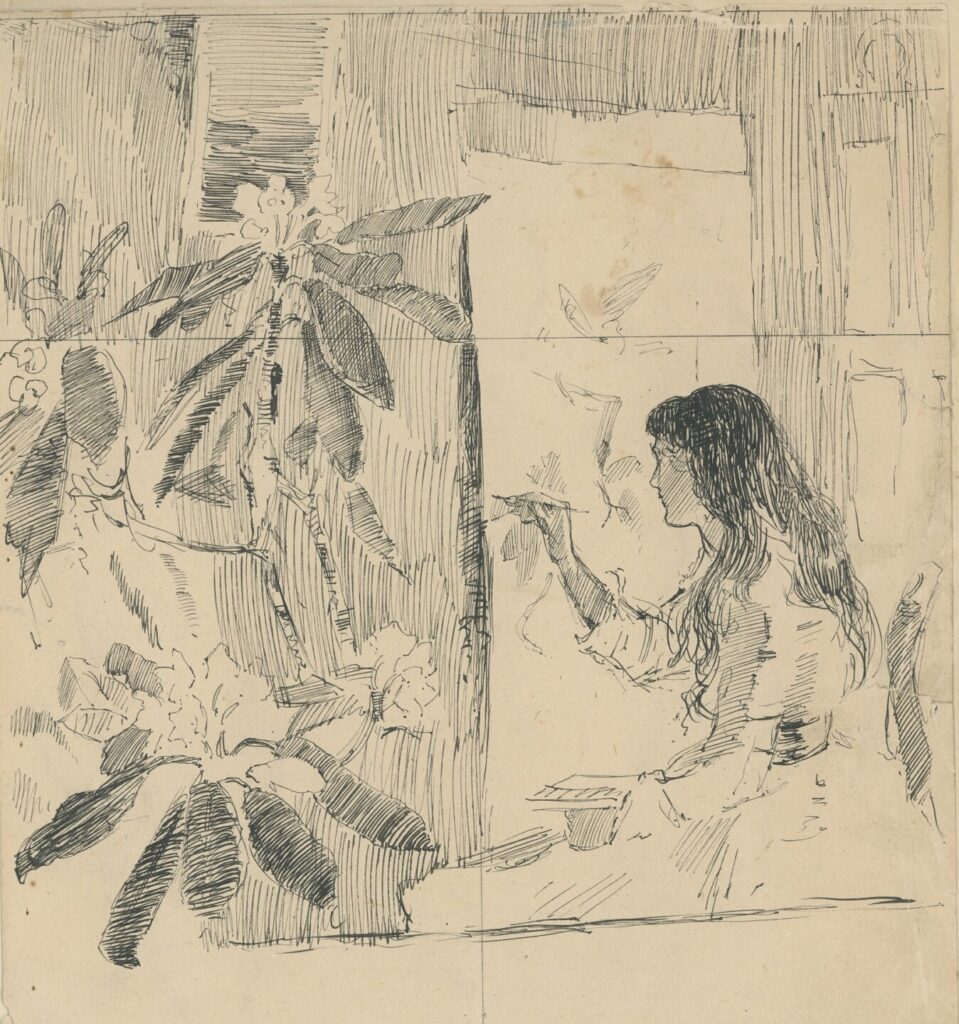

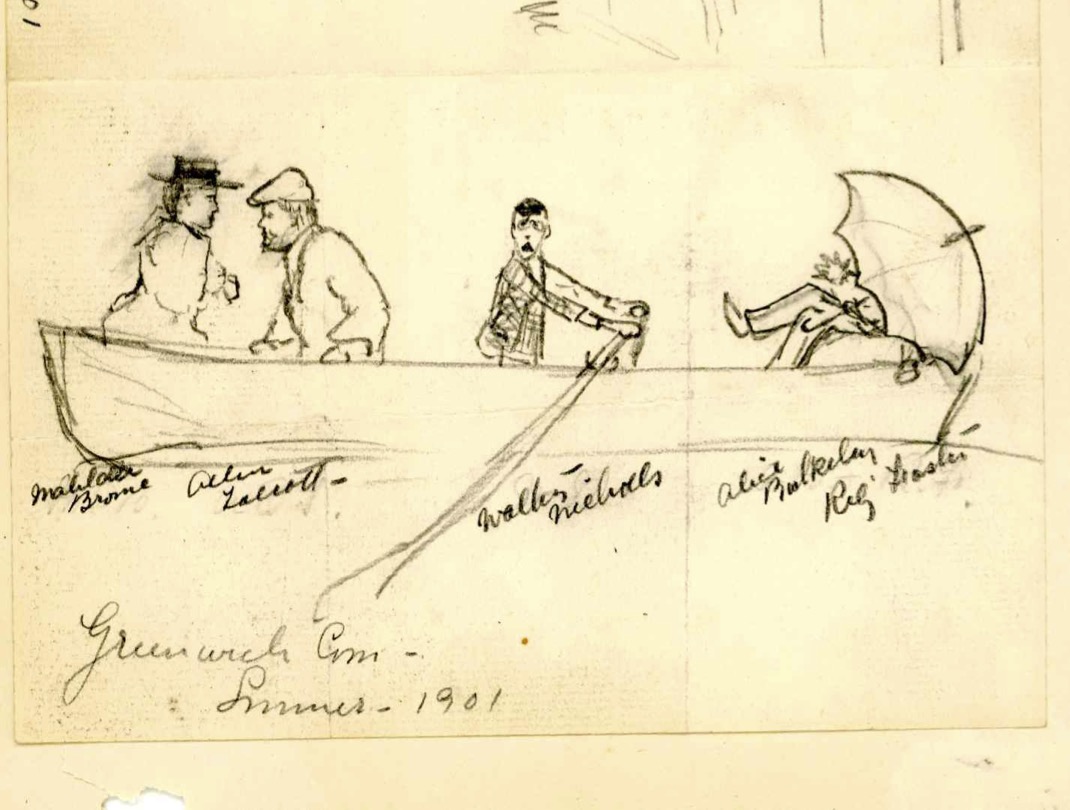

Preserved in Browne’s scrapbook are publicity photographs, snapshots of herself at work, original pencil sketches, exhibition invitations and catalogues, and certificates of membership in arts organizations that trace the details of her career. Glued to the scrapbook’s first page is an 1888 drawing by her teacher, New York artist and illustrator Eleanor Greatorex, showing Browne at age 19 intently focused on her painting. Also saved in the scrapbook is a whimsical caricature sketch drawn in Greenwich in 1901 by artist Allen Butler Talcott, depicting Browne in a tipsy boat together with other artists whom she later joined in Old Lyme.

Eleanor Greatorex, Sketch, 1888. Ink on paper. From Matilda Browne Scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

Allen Butler Talcott, Sketch of artist friends, 1901. Matilda Browne Scrapbook. Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

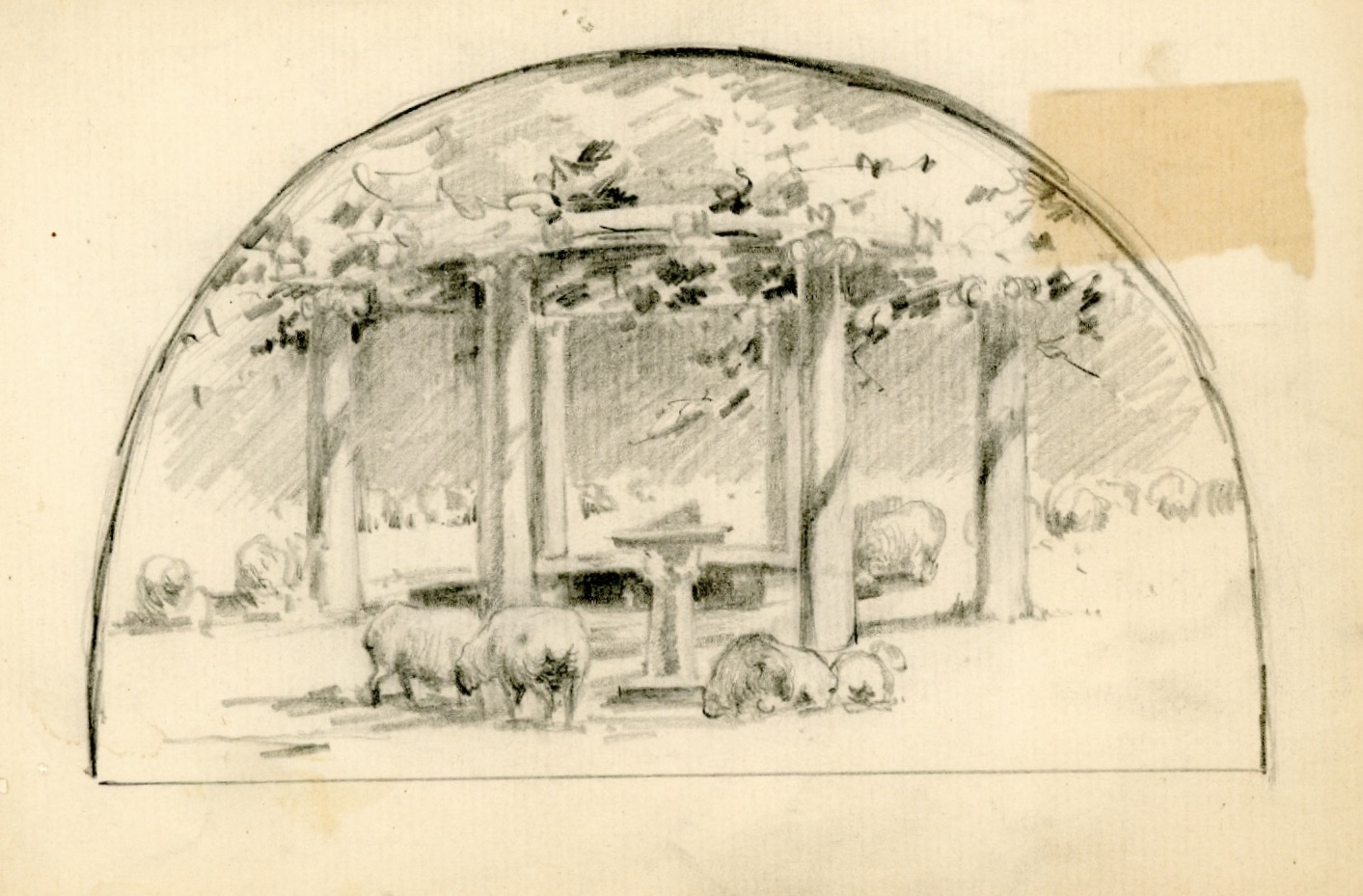

Matilda Browne, Sketch of Sheep around a garden pavilion, n.d. Matilda Browne Scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

Dozens of newspaper clippings pasted into the scrapbook trace the work Browne exhibited in multiple venues. The reviews document her expanding reputation as she moved beyond flower paintings and portraits to the exacting and traditionally male task of painting livestock. An undated clipping from the New York Times, “Studios of Women Artists,” notes, for example, that unlike most women, Browne was “particularly fond of cows.”

Artist and art critic Arthur Hoeber transcribed for Browne an April 1911 review that appeared in The Globe: “Matilda Browne has some cattle under The Summer Moon, which is strong in the painting and very masculine—if that be complimentary, and it is so meant—and shows this woman to have a good knowledge of anatomy and drawing of the animals.” Hoeber quipped in his accompanying note: “And to think of our little ‘Guyber,’ growed hup a big man and paintin’ good stuff. O tempora, o mores!”

Summary of Matilda Browne works on view at Ogontz School for Young Ladies, Ogontz, Pennsylvania. Ogontz Mosaic XII, no. 8 (May 1895), p. 11, clipping in Matilda Browne Scrap Book, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

Other notes from friends and acquaintances, offering praise for her talent and encouragement of her livestock painting, are among the scrapbook’s most revealing items. One of the most touching notes comes from Bruce Crane, a tonalist painter and later a member of the Lyme Art Association, written before the National Academy of Design Show in 1896: “If I have helped you in the years gone by believe, trust, I will help you in the years to come. Have faith in yourself. God never gave anyone more talent than you possess. I have seen it bud and bloom, I shall see it yet flow with greater beauty. May health be with you, power is already thine.”

After purchasing one of Browne’s sketches, Lyme artist Charles Vezin wrote her an appreciative note in September 1911. “Your work appeals to me by its sincerity, poetic feeling and strength, that much abused art adjective, strength without the spurious masculinity that so many women artists effect,” Vezin remarked. “The stumbling block of most artists of your sex is twofold, the refusal to become craftsmen and the desire to ‘paint like a man’. You have achieved the craftmanship and you do not need to try to paint like a man.”

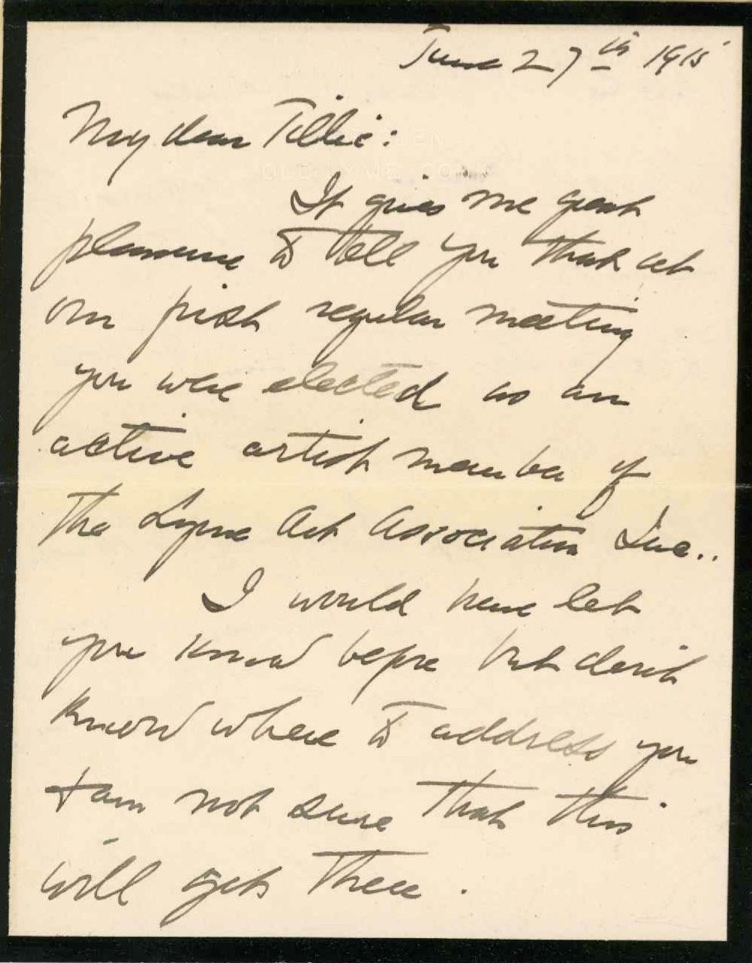

A letter from Clark Voorhees notified Browne in 1915 that she had been elected to the Lyme Art Association now that the jury included artists sympathetic to her inclusion. Her election made her the “first active art member of your sex in the association,” Voorhees wrote, “though why sex should butt into the art question has always been a puzzle to me; they are each large questions in themselves as you know but we have had certain ones in our group that have always been firm in their opposition, much to the annoyance of some others of us —”.

Clark Voorhees to Matilda Browne, June 27, 1915. Matilda Browne Scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

Browne’s scrapbook offers not only a collage of documents and ephemera reflecting the life of a key Lyme Colony artist, but something more enduring: the record of a determined and independent woman who developed her strong technique and discerning artistic eye despite the bias and skepticism that pervaded the male art world in her era. The fact that she collected and preserved these markers along the artistic trail she blazed speaks to Matilda Browne’s desire to mark her passage and the pride she took in her accomplishments.

Matilda Browne Sketching Outdoors, Dover Plains, N.Y., 1910. Matilda Browne Scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the FloGris Museum

Selected references:

—Letter from Arthur Hoeber, May 23, 1911, includes excerpt from The Globe, April 12, 1911.

—Letter from Charles Vezin, September 3, 1911, with letterhead: “Wildmere House, Minnewaska, Ulster Co. N.Y.” and note: “Permanent address 349 Broadway, N.Y.”

— Letter from Clark S. Vorhees, June 27, 1915, with embossed letterhead: “Kerguen/Old Lyme, Conn.”

—The New York Times (Calf’s Head exhibited at NAD in 1892 so probable year for article is 1892), “Studios of Women’s Artists: Gotham’s Gentle Painters Chat About Their Work in Landscape and Portraiture.”

—Note from Bruce Crane, 1896, “Midnight Sunday.”