by Carolyn Wakeman

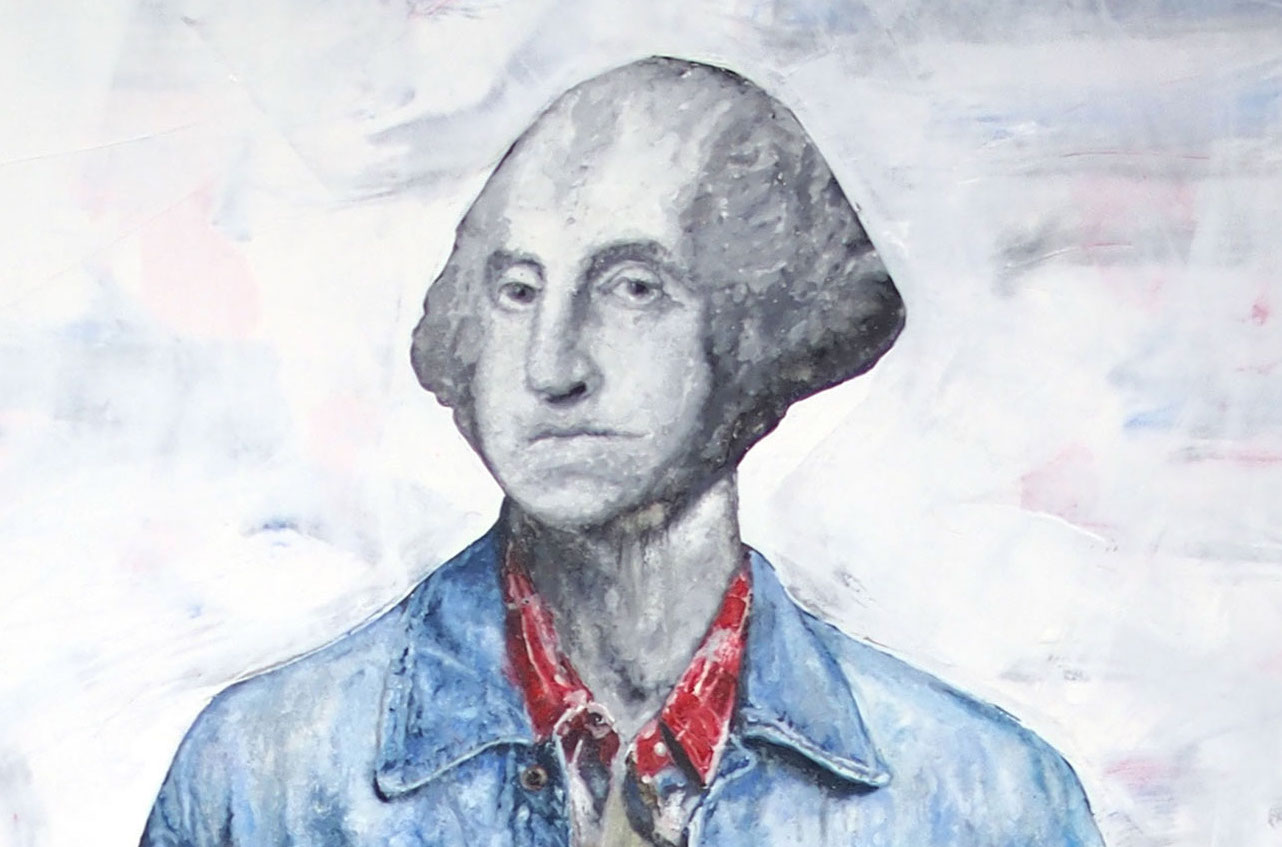

Featured image: Jac Lahav, George Washington: Over the Mountain (detail), 2018. Collection of Jeff and Betsey Cooley

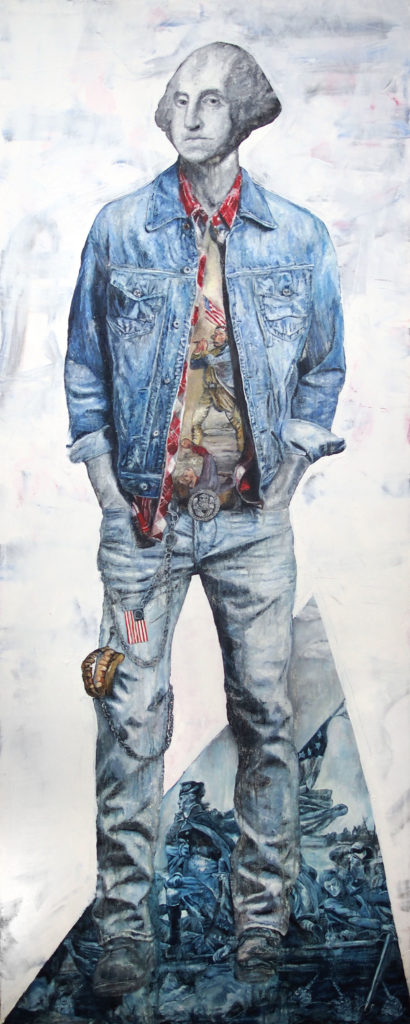

The Florence Griswold Museum’s riveting spring 2019 exhibition The Great Americans: Portraits by Jac Lahav offers vividly provocative interpretations of the myths and legends that swirl around America’s iconic heroes. Several of the famous Americans that Jac Lahav depicts in layered portraits painted on nearly-life size canvases played a role, both real and imagined, in Old Lyme’s past. According to local lore George Washington slept in the home of merchant John McCurdy on today’s Lyme Street, used the house on April 10, 1776, as his headquarters, and danced that evening in the upstairs ballroom at Peck Tavern a mile north along the main road through town. Historical documents make us question those stories.

Jac Lahav, George Washington: Over the Mountain, 2018. Collection of Jeff and Betsey Cooley

A letter that George Washington wrote in New York on April 15, 1776, specified the route of his recent travel from Boston. “I came thro Providence, Norwich and New London in order to see and expedite the embarkation of the Troops,” he advised John Hancock. An earlier letter written from Cambridge on April 3 had explained his decision to leave immediately after the British fleet sailed from Boston harbor, its destination unknown. Rumors swirled that British ships might attempt to blockade New London’s harbor before proceeding to New York, and General Washington needed to speed preparations. His troops were already on the march, and the Continental navy would oversee their transport from New London to New York via Long Island Sound. In New London where he spent the night of April 9, he conferred with Commodore Esek Hopkins aboard the warship Alfred and reviewed fortifications on both sides of the Thames River. After reaching New York he worried about weather delays and noted that “the badness of the Roads & difficulty of procuring Teams for bringing the Stores, baggage &c. have greatly prolonged their arrival.”

General Washington had sent his wife ahead via Hartford to New Haven while he traveled on the “lower road” with an adjutant general and two aides de camp, one of whom, William Palfrey, kept a record of their expenses but did not enter dates. The expense record along with General Washington’s correspondence offer a close-up view of the journey from Boston, but neither mentions Lyme. Palfrey listed a charge of four shillings for mending a carriage in New London and the subsequent purchase of a salmon either there or en route. He then listed expenses “at Leighs Saybrook” and two charges for the Connecticut River ferry. The next entry shows a payment of more than two pounds in Guilford. General Washington arrived in New Haven on the morning of April 11, but where he spent the night of April 10 is not known.

More than a century later Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury wrote in an extravagantly detailed family history published in 1892 that “it naturally fell” to her great-grandfather John McCurdy “to be the host of Washington when, on the 9thof April 1776, he passed a night in Lyme on his way from Cambridge, after taking command of the patriot-army.” Mrs. Salisbury, a neighbor later explained, regaled visitors to her ancestral home in Old Lyme with descriptions of the bedroom behind the living room as the “Washington room.” Her friend Martha J. Lamb, editor of the Magazine of American History, echoed that claim in an obituary tribute to Mrs. Salisbury’s father Charles J. McCurdy. “Many pieces of furniture,” Martha Lamb wrote in 1891, “are associated with the visit of George Washington on April 9, 1776, when he spent a night under their roof on his journey from Cambridge to New York.”

Curiously a lengthier article that Mrs. Lamb wrote about Lyme’s venerable families for the centennial issue of Harper’s Magazine in 1876 did not mention George Washington’s night in Lyme. It stated that the McCurdy house “has historical significance through certain Revolutionary events” but noted only that the north chamber had been occupied by General Lafayette “for several days during the Revolution, when he was entertained by John McCurdy, while resting his troops in the vicinity.” Evelyn Salisbury and her father had provided information for the Harper’s article and had also edited Martha Lamb’s early draft, which suggests that the claim to Washington’s visit originated sometime between 1876 and 1890.

John McCurdy House, Noyes-Ely Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

A skeptical neighbor queried the Washington-slept-here story. In a family memoir published in 1928, Katharine Ludington, who lived across the street from the McCurdy home and described “Cousin Evelyn’s” extravagances with warmth and humor, explained the evolution of her neighbor’s George Washington assertion. “When cross-questioned, she had to admit that she arrived at this by a process of deduction,” Katharine Ludington wrote. “Washington was known to have passed through Lyme on a certain date on his way to New Haven,” and Cousin Evelyn therefore “argued that of course he would have to spend one night on the way, that he would naturally choose Lyme as the stopping point—what town could compare for charm?” Although Ludington family members “were in the habit of referring facetiously to the ‘Washington bed,’” Mrs. Salisbury said “years later” that she had discovered “some old journals” which showed that “George Washington did pass through Lyme, he did spend the night here and stayed at Squire McCurdy’s.” Katharine Ludington does not clarify that discovery. Whether the old journal was an 1890 issue of the Pennsylvania Magazine of History, which published an account of Washington’s itinerary and stated, providing no source, that he spent the night of April 10, 1776, at the home of John McCurdy, is not known. But after 1891 George Washington’s overnight visit to Lyme became fixed in public memory.

Annotations to Palfrey’s expense list also query whether George Washington slept in Lyme on April 10. If on April 11 he crossed the Connecticut River by ferry, paid costs at “Leigh’s” in Saybrook, paid additional costs in Guilford, and still reached New Haven the same morning, he would have had to travel with unusual speed. He certainly would have had no time to establish a “headquarters” in Lyme, nor is it likely he spent the previous evening dancing after his busy preparations in New London, even if there was a tavern with an established ballroom on the old Post Road. “Just when it became a tavern has not been ascertained,” Old Lyme historian Susan Hollingsworth Ely stated after conducting a detailed title search for Peck Tavern. “It is said that during the Revolutionary War food and clothing were handed out to the soldiers as they passed by,” she noted but offered no evidence for that assumption.

Peck Tavern, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

Susan Ely’s search of the land records established that Capt. John Peck built a new house on the site of an earlier dwelling sometime after purchasing the property in 1769, but she found nothing in his estate inventory in 1785 “to indicate it was an Inn.” An early sign for Peck Tavern still exists and shows the Peck family’s coat of arms but cannot be dated. Future research may reveal whether Capt. John Peck, or his son John Peck, Jr., or perhaps his brother Nathaniel Peck, whose estate inventory, according to a notice in the Connecticut Gazette in July 1781, stated that his mansion house in Lyme was “well situated for trading or tavernkeeping,” first operated the Peck house as an inn. For now no evidence supports the claim that General Washington danced at Peck Tavern on April 10, 1776. It is far more likely he traveled with little delay after leaving New London, proceeded to the ferry, crossed the Connecticut River, and spent the night of April 10 in Guilford, which allowed him to travel the remaining twelve miles and reach New Haven on the morning of April 11.

George Washington is said to have slept in many places, and the effort by Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury to embellish local history and link her residence with America’s founding father is not uncommon. Veneration for the first President proliferated after his death in 1799, and the Colonial Revival in the late 19th century gave rise to a new round of legends that we seldom dissect because of our own contemporary desire to find connections with “Great Americans.”

Note on Sources:

Special thanks to Amy Kurtz Lansing for assistance. For George Washington’s “Expenses of Journey to New York, 4-13 April 1776” and accompanying references to his correspondence, see Philander D. Chase, ed., George Washington, Revolutionary War Series 4:40-42 (Charlottesville, 1991). For the claim that the McCurdy house served as General Washington’s headquarters, see brochure “Walking Tour of Lyme Street,” Old Lyme Historical Society, 2018. For the claim that Washington danced at Peck Tavern, see Kimberly Drelich, “Old Lyme’s Historic ‘Peck Tavern’ up for Sale,” The New London Day (May 12, 2018), https://www.theday.com/article/20180512/NWS01/180519779 (accessed March 28, 2019). For William Baker’s statement that Washington slept in Lyme see Pennsylvania Magazine of History, Vol. 14, No. 2 (July 1890). For Martha J. Lamb’s articles see “Lyme: A Chapter of American Genealogy” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (February 1876), p. 319, and Magazine of American History, Vol. 26, No. 5 (November 1892), p. 323. For Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury’s claim see Family Histories and Genealogies, Vol. 1 (1892), p. 55. For Katharine Ludington’s comments about Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, see Lyme—and Our Family (New York, 1928), pp. 100-101. For Susan Ely’s research on Peck Tavern see Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6, Lyme Historical Society Archives.