By John E. Noyes

UPDATED: February 2023

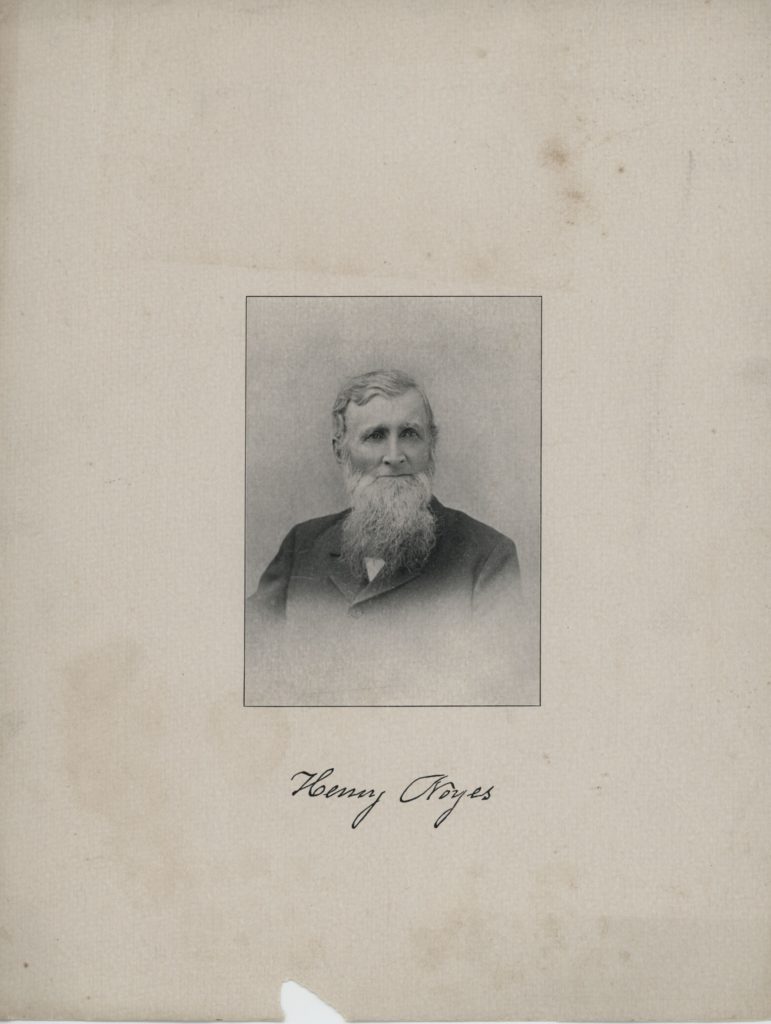

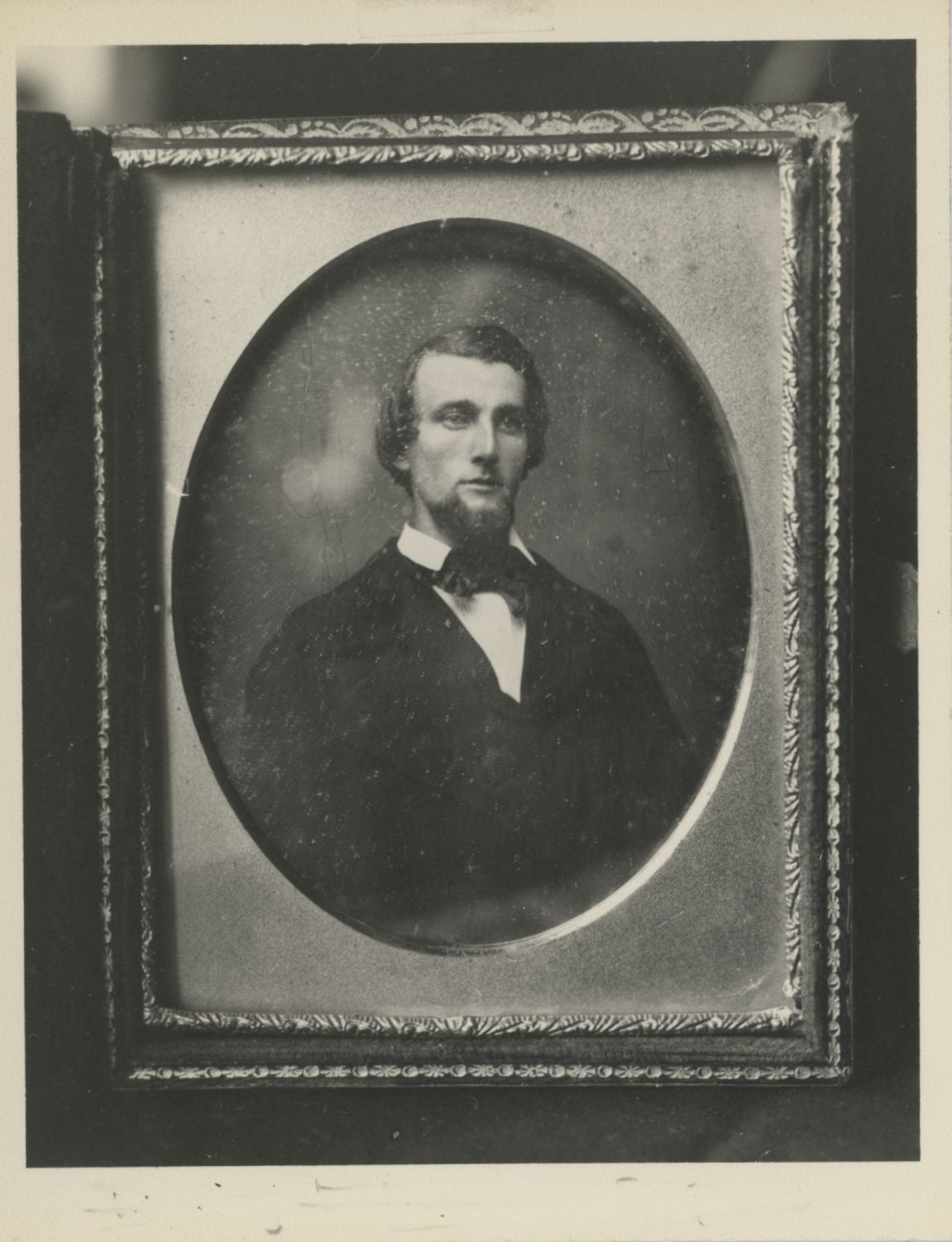

Featured Image: Henry Noyes, ca. 1849-1850, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Henry Noyes (1826-1917), the fourth of eight children and the oldest son of Enoch Noyes (1789-1877) and Clarissa Dutton (1799-1838), was one of several young Lyme men who caught “gold fever” and traveled to California in the mid 19th century. For this young farmer from rural Connecticut, dreams of making a fortune by mining gold did not pan out, but Noyes stayed in California for 11 years and earned a substantial income hunting and fishing. Few of Noyes’s letters home survive, but they provide tantalizing glimpses of his life in California, and his journal records the business details of many of his hunting ventures.

After President James K. Polk, in December 1848, confirmed the discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada, the gold rush began in earnest, but adventurers on the east coast had no easy way to get to California. Traveling overland by wagon – the first transcontinental railroad was not completed until 1869 – took about half a year, and the trip was fraught with peril: difficult routes across mountains and deserts, the risk of cholera, and the threat of Indian attacks. Some booked sea passage for the 14,000-mile voyage around Cape Horn, which typically took five or six months and also presented challenges. Noyes’s friend Arthur Champion of Lyme, who crewed a ship around the Horn, wrote his sister from San Francisco in September 1853 that he had been stuck off the Cape for “thirty seven days with constant westerly winds with rain, hail and snow” and had suffered reduced water rations.[1]

Noyes himself chose a third route, traveling with his friend Horace Champion by sea to Panama, hiking across the Isthmus, and then sailing on to San Francisco, arriving in mid 1850.[2] Although the Panama route was quicker than other options, it too was not easy. Panama travelers faced the hardships of ocean voyages and a 30-mile trek through the jungle. They encountered criminals, risked exposure to the dreaded Chagres fever, and faced uncertain travel connections up the Pacific coast.[3] Noyes’s journey was not uneventful. “Some rascal stole my coat crossing the Isthmus,” Noyes wrote his sister Ellen Chadwick. “[H]e did not get my money,” Noyes continued, “but I can get rid of that fast enough myself without any bodys helping me.”[4]

PANAMA Sailing Card, © Mystic Seaport Museum, G.W. Blunt White Library,

Sailing Card Collection, Coll. 112 – Box 2, Folder 8

After reaching the Pacific coast, Henry Noyes survived a challenging passage to San Francisco on the steamer New World. The ship picked up passengers in Panama after her four-and-a-half-month trip from New York around Cape Horn, losing 15 crew members to yellow fever en route. During the voyage from Panama to San Francisco the New World was forced to stop – once for repairs after her steam chest burst during a severe 36-hour gale off the coast of Mexico, and twice to seek coal for fuel. On July 11, 1850, however, after three weeks on board, Henry Noyes, Horace Champion, and 215 other passengers arrived safely in San Francisco.[5]

Not only was the trip to California long and difficult, it was expensive. For those traveling by sea, the cheapest berth cost $150 or $200 one way, and outfitting oneself for the gold fields required additional expense. For provisions and passage from New Haven, the typical cost was $500.[6] At a time when the average farm laborer in New England earned about $155 per year (with board), a journey to California could not be undertaken lightly, if it could be afforded at all.[7] Some men from Lyme found their way to California by working as crew members on vessels.[8] Others organized or joined mining companies that attracted investors to fund voyages.[9]

Several Lyme men sought their fortunes in California. Fred Green, one of Horace Champion’s and Henry Noyes’s acquaintances, traveled with them to California. On his arrival in San Francisco, Noyes reported that Roger and Henry Griswold, who had reached San Francisco in November 1849, had headed to the mines.[10] Noyes would work in California with various Lyme residents. Enoch Noyes, Jr. joined his brother in several western endeavors, and Henry Noyes also worked with Horace Champion, Marcus Champion, Erastus Huntley, and John Lester. Other contemporaries from Lyme also caught gold fever, but their paths apparently did not cross Noyes’s in California.[11]

Henry Noyes disparaged San Francisco when he arrived in the summer of 1850 – “the wind blows and the sand flies so you cant see any thing at all,” and “flannel and over coats will not keep a fellow warm” – but he planned to leave for the mines in a few days. “[W]hat time I stay will be principally in the diggins,” he predicted.[12]

Noyes and Horace Champion did attempt gold mining, but, like many, they were disappointed. “Horace and I have come down again” to San Francisco from the mines, Noyes wrote his sister Martha in September 1850, “not finding room to lay a pick or shovel down without putting it on somebody’s head. The mining is completely used up,” and those who “could get home have gone while the rest are doing nothing.” Except for the “one in a thousand” who “makes his pile,” Noyes continued, miners’ efforts had “turned out a complete failure.” Men had lost their life savings and wasted months of work building dams to sluice gold. “If you know of anyone that thinks of coming here give him a dose of Arsenic to start on. … I thunderingly hate to come home with out something, but I don’t see but I shall have to.”[13]

Noyes faced other adversity as well. He suffered illnesses[14] and complained of living conditions:

I like this country first rate but the fleas are so thick that you can take no peace at all. I have killed as many as 50 fleas in my pants just taking them off besides … thousands them of [sic] jump off before I get a chance to slay them. So for that very reason I couldn’t always stay out here.[15]

Noyes also apparently was swindled, writing his sister Martha in July 1852 that after encountering “dealing damn scoundrels” he had recently managed to get “just about square with the world again.”[16] How Noyes reacted to the physical violence and temptations of San Francisco is not known, but Lyme native Arthur Champion was shocked:

This is one of the most miserable places in the whole world, I believe. Last Sunday four men were stabbed around the docks where we lay. If a man is shot in the streets nothing is thought of it. Gambling houses are open Sundays as any other day. Horse races and cock fights always come off Sunday.[17]

For his part, Noyes reported only minor indulgences. He wrote to his sister that “a gang of us” planned on “going to Santa Clara to a bear fight” in August 1852, and he occasionally bought liquor.[18]

Noyes’s hardships paled in comparison to the tragedies that befell some Lyme men who ventured to California. Dr. Shubael Fitch Bartlett of Lyme died of dysentery in Benica, California, shortly after arriving there in 1849.[19] Edward Comstock spent seven months traveling around Cape Horn to California in 1849 and married there in 1854, but then suffered the deaths of his wife and infant child a year later.[20] Martin Huntley, who was born in Lyme before moving with his family to New Lyme, Ohio, in 1812, died on board a ship sailing from Panama to San Francisco.[21]

Tragedy also struck Noyes’s friends. His traveling and mining companion Horace Champion, who returned home to Lyme and then captained a ship back to California in 1853, died from dysentery he contracted in San Francisco.[22] Erastus Huntley was murdered in lower California in 1862.[23] Marcus Champion, who teamed with Noyes in various endeavors, was killed in a steamboat explosion on the Sacramento River in 1865.[24]

Despite his tribulations, Noyes persevered, pursuing a variety of business ventures during his 11 years west. In 1852 he took a job on a large ranch harvesting grain and operating reaping and thrashing machines for $100 a month plus board, a handsome wage. Since “the rest of the men get 50,” Noyes wrote to his sister Martha, “you can see that old Hen is not quite so much of a stragler [sic] as [a] great many people took him to be.”[25] By mid 1852, Noyes had bought a half share of a shanty and a half share of a six-ton schooner named Mist.[26] Noyes planned to hire out the Mist to transport grain, and he reported some earnings from “freight,” likely from use of the schooner.[27] He also probably used the vessel in his wide-ranging hunting expeditions.

Most of Noyes’s considerable financial success came from shooting ducks to supply the San Francisco market. He teamed with different partners in different years to hunt waterfowl in the undeveloped marshes and streams around San Francisco Bay. To travel from one end of his duck hunting range to the other – from Suison Bay northeast of San Francisco to south San Francisco Bay – Noyes had to sail about 100 miles.[28] His surviving business records, which he kept in a bound leather journal, detail his hunting locations and kills during five seasons (1855-1856 to 1859-1860); summary accounts indicate that he started hunting as early as 1850.[29]

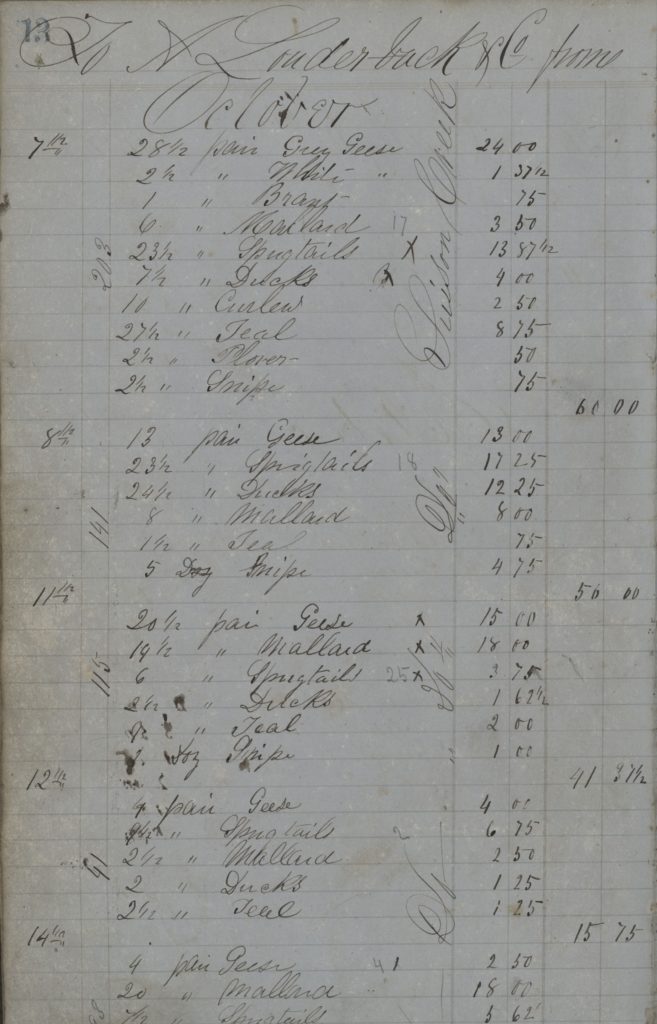

The San Francisco Bay wetlands were home to plentiful and varied waterfowl. On October 7, 1855, for example, Henry Noyes and two friends from Lyme, Marcus Champion and John Lester, shot 203 birds at Suison Creek, some 50 miles northeast of San Francisco. Their take included various species of ducks and geese, brant, curlew, teal, plover, and snipe.[30] Since each bird could be sold for about 30 cents, that day’s effort yielded $60.

Excerpt from Henry Noyes Journal, Noyes-Ely Collection, Box 5, File 16, LHSA

One of Henry Noyes’s duck decoys, engraved “San Francisco, 1855,” Private Collection

A poor day’s hunting would bring less than $10 while an exceptionally good day could yield well over $100 (approximately $3,750 today).[31] Noyes’s journal records $24,220.75 from sales of game from 1850 through 1861.[32] Business expenses included shot, powder, caps, wharfage, and food supplies (e.g., salmon, meat, flour, butter, beans, potatoes, coffee, and tea).[33]

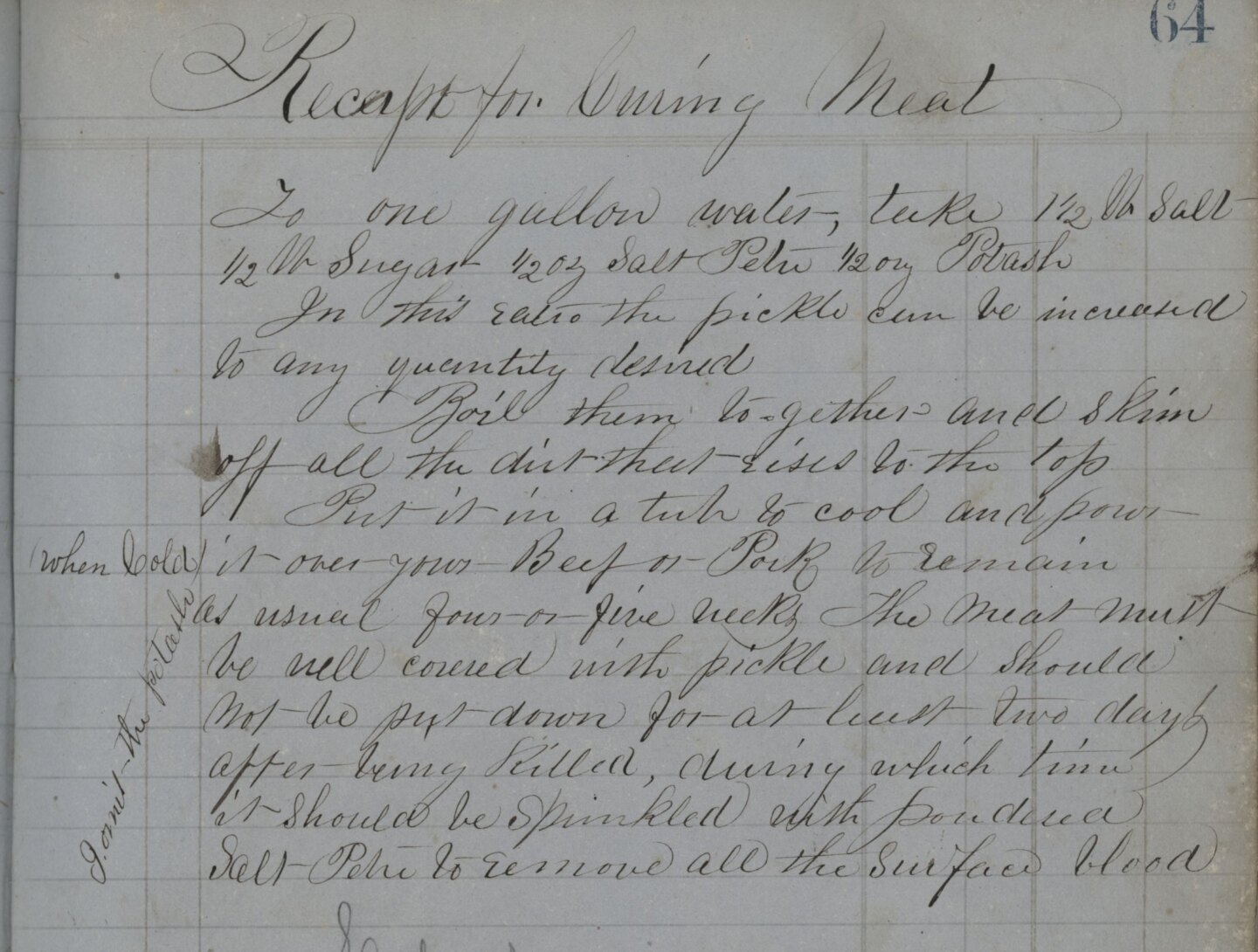

Noyes reportedly hunted big game as well as ducks while out west, venturing as far north as Washington.[34] No records of any such shooting expeditions have been found, although he did kill a few animals while hunting ducks, and his journal includes a recipe for curing meat.[35] Since duck hunting season ran from late summer to early spring, Noyes may have spent time hunting game during the spring and summer.

Recipe for curing meat from Henry Noyes Journal, Noyes-Ely Collection, Box 5, File 16, LHSA

Noyes also made money fishing. On August 4, 1860, William F. Walton & Co. of San Francisco entered a salmon fishing contract with Henry Noyes, Enoch Noyes, and Judson Baldwin, a former duck hunting partner from Oregon. During “the coming fishing season” Baldwin and the Noyes brothers agreed to “devot[e] their full time and attention” to fishing for salmon, curing it, and packing and shipping it to San Francisco. For its part, the company was to supply equipment and fishing grounds on the Rouge River in Oregon and was to advance money for salting and shipping. The company would then sell the salmon on consignment and keep a percentage of net profits.[36] After this salmon fishing venture, Henry Noyes returned briefly to hunting before leaving California in 1861.[37]

The resourcefulness, resilience, and versatility that brought Henry Noyes success farming, hunting, and fishing during his 11 years out west also characterized his later years. On returning east he married his second cousin Mary Jane Ely (1838-1922) in Baltimore on November 19, 1861, and purchased a “fine farm” at Mt. Ararat in Cecil County, Maryland.[38] After the Civil War, he returned to his home town of Old Lyme, where he made his living fishing for shad, building boats, farming, and serving in various capacities in town government.

Henry Noyes as an elderly man, LHSA

Although Henry Noyes did not rely on duck hunting as his livelihood in Old Lyme, he kept his hand in the sport. He taught his son Jack – John Ely Noyes (1862-1948), Mary Jane’s and Henry’s only child (and the author’s grandfather and namesake) – to hunt. A record titled “Lyme Ducks Killed in 1880 by J.E.N.” contains 45 entries; underneath that list Henry Noyes noted, “9 of these ducks were killed by H. Noyes.”[39]

Henry Noyes holding goose, LHSA

When Henry Noyes died in 1917 at age 91, he was, according to a note in the Norwich Bulletin, “the last of Old Lyme’s ’49-ers.”[40]

The author thanks Carolyn Wakeman, and Patrick Ford and Maribeth Quinlan of the Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center, for their assistance with research.

[1] Letter from Arthur Champion to Sister [probably Angeline], San Francisco, Sept. 25, 1853, Plimpton-Ely Papers, Box 2, Champion file, LHSA [hereafter 1853 Champion Letter]. “Henry Noyes is now in the cabin,” Champion wrote, “and sends his respects.”

[2] Genealogical and Biographical Record of New London County (Chicago, 1905), p. 720; “Had a Varied Career,” New London Day, June 19, 1917, p. 8

[3] For descriptions of hardships facing travelers en route to California, see H.W. Brands, The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream (New York, 2002).

[4] Letter from Henry Noyes to Sister [Ellen N. Chadwick], San Francisco, Sept. 11, 1850, Noyes-Ely Papers, Box 1, LHSA [hereafter July 1850 San Francisco Letter].

[5] Ibid.; “Arrival of the New World,” Daily Alta California, July 12, 1850, in Maritime Heritage Project, “Ship Pasengers – Ship Captains – New World,” https://www.maritimeheritage.org/passengers/nw071150.htm.

[6] Elizabeth Normen, “The Gold Rush: John E. Brockett Goes for the Gold!,” Connecticut Explored, Winter 2015-2016, p. 48. See also Brands, pp. 72, 123.

[7] “History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928,” Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics No. 604 (1934), p. 163, available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112104053548&view=1up&seq=181. Noyes apparently could rely on his family in Connecticut as a financial safety net. “[D]on’t mention about sending me money,” he wrote in one letter to his sister Martha. “If I stand in need of it I will send for it.” Letter from Henry Noyes to Sister [Martha], San Mateo, July 25, 1852, Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 24, LHSA [hereafter 1852 San Mateo Letter].

[8] Lyme residents who crewed ships to California included Edward Comstock, Daniel Andal, and Noyes’s friends Horace Champion and Arthur Champion. Edward Comstock served as the second mate on the Alfred, a 65-foot, 90-ton schooner, on a 210-day passage around Cape Horn to San Francisco. Autobiographical Journal of Elijah Comstock (1850-1857) (typed copy), pp. 20-21, Manuscripts, Folder 35, LHSA; Permanent Enrollment Certificate No. 74, Port of New London, Sept. 9, 1847, Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center, New London Customs Records, Certificates of Enrollment, 1840-1852 (microfiche); Crew List for Schooner Alfred, Mar. 7, 1849, Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center, Crew Lists, New London Customs Records, Outgoing Vessels, 1848-1863 (microfiche); Maritime Heritage Project—1846-1899, “Merchant Ships in Port,” San Francisco, Sea Ports—Sea Captains, https://www.maritimeheritage.org/inport/1849.htm (listing for Nov. 3, 1849). Sixteen-year-old Daniel A. Andal was a crew member on board the ship Corea bound from New London for San Francisco. Crew List for Ship Corea, Mar. 11, 1850, Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center, Crew Lists, New London Customs Records, Outgoing Vessels, 1848-1863 (microfiche). Horace Champion, who traveled to California with Henry Noyes in 1850 and attempted mining with him, was primarily a sailor, first going to sea at age 14 with his uncle, Capt. Daniel Chadwick. He made several trips to China and captained a ship to San Francisco. Francis Bacon Trowbridge, The Champion Genealogy: History of the Descendants of Saybrook and Lyme, Connecticut (New Haven, 1891), 1:136. Arthur Champion (1834-1867), who wrote his sister from San Francisco about the challenges of sailing around Cape Horn, 1853 Champion Letter, remained a seaman and did not stay in California.

[9] Dr. Shubael Fitch Bartlett of Lyme, who went to California in 1849, served as the physician and treasurer of such a company. The New England Historical & Genealogical Register (1850), 4:195-196. Some mining companies sold shares to passive investors to raise money. Phyllis Kihn, “Connecticut and the California Gold Rush: The Connecticut Mining and Trading Company,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin (1963), 28:1-2. In addition, some ships transported goods to be sold in California.

[10] July 1850 San Francisco Letter. Lyme residents Roger Griswold (age 24), Henry Griswold (21), and William Maynard (24) had sailed to California on board the Willimantic. U.S. Customs Office, Crew List for Schooner Willimantic, Mar. 13, 1849, in Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center, Crew Lists, New London Customs Records, Outgoing Vessels, 1848-1863 (microfiche). The Willimantic left New London on March 17, 1849, arriving in San Francisco on November 2 of that year. She was a small two-masted, one-deck schooner carrying only 20 passengers and crew members; passage around Cape Horn during an Antarctic winter was undoubtedly arduous. For more on the Willimantic, see “Find Your Family: Around Cape Horn and Back Again!,” http://notyourgrandmothersfamilyhistoryblog.com/around-cape-horn-and-back-again-part-i/; “Write the Story: Around Cape Horn and Back Again!,” http://notyourgrandmothersfamilyhistoryblog.com/around-cape-horn-and-back-again-part-ii/.

[11] See notes 8-9, 19-21 and accompanying text.

[12] July 1850 San Francisco Letter.

[13] Letter from Henry Noyes to Sister [Martha], San Francisco, Sept. 11, 1850, Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 21, LHSA [hereafter Sept. 1850 San Francisco Letter].

[14] Ibid. (unspecified illness, requiring doctor visit); July 1850 San Francisco Letter (“severe cold”); 1852 San Mateo Letter (toothache).

[15] 1852 San Mateo Letter.

[16] Ibid. See also Letter from A. Loudenback, San Francisco, Mar. 10, 1862, to Henry Noyes, Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 17, LHSA, which recounts attempts to collect debts on Noyes’s behalf after he had left California.

[17] 1853 Champion Letter.

[18] 1852 San Mateo Letter; Henry Noyes Journal, July 14, 1855, Noyes-Ely Collection, Box 5, File 16, LHSA, p. 8 [hereafter Henry Noyes Journal].

[19] The New England Historical & Genealogical Register (1850), 4:195-196.

[20] Autobiographical Journal of Elijah Comstock, pp. 20-21, 26-27.

[21] Virgil W. Huntley, John Huntley, Immigrant of Boston & Roxbury, Massachusetts and Lyme, Connecticut, 1647-1977, and Some of His Descendants (Moodus, CT, 1978), 1:233-234 [hereafter Huntley Genealogy].

[22] Letter from Arthur Champion to Brother and Sister, At Sea, Dec. 4, 1853, Plimpton-Ely Papers, Box 2, Champion file, LHSA; Francis Bacon Trowbridge, The Champion Genealogy: History of the Descendants of Saybrook and Lyme, Connecticut (New Haven, 1891), 1:136.

[23] Huntley Genealogy, 1:249-250; Ivy Huntley Horn, John Huntley of Lyme, Connecticut and His Descendants (Herndon, VA, 1953), p. 158. Several men named Erastus Huntley were born in or near Lyme in the early 19th century, but Erastus Brockway Huntley (1829-1862), referred to as a whaler and sailor from Hamburg, is the only one noted as having been in California. This likely was the Erastus Huntley who became one of Noyes’s hunting partners.

[24] Champion Genealogy, 1:154.

[25] 1852 San Mateo Letter.

[26] Ibid. Noyes partnered with Marcus Champion from Lyme to buy the Mist, but Champion sold his share a year later. Letter from Henry Noyes to Sister [Martha], San Francisco, July 25, [1853], Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 23, LHSA. Noyes reported in this letter that he also had sold his house; if Champion owned the other half share of that “shanty,” the two may have been disaggregating their financial affairs at the time. Noyes may have bought another house later, since his journal records the collection of $30 for three months’ rent from Joseph Frost, another hunting companion, in 1858-1859. Henry Noyes Journal, p. 77.

[27] “After I get through thrashing, Mark [Marcus Champion] and I will get the grain to carry to town by water I expect.” 1852 San Mateo Letter; Henry Noyes Journal, p. 325.

[28] Today this range, which includes Suison Bay to the northeast, San Pablo Bay to the north, the central region of San Francisco Bay, and the South Bay, encompasses approximately 1,600 square miles. However, according to the U.S. government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, the water area “has shrunk by one-third since the California gold rush. Before 1850, the region sustained 540 square miles of freshwater wetlands and 310 square miles of salt marshes; today, only 48 square miles of undiked marshes remain of the original 850 square miles.” “San Francisco Bay Environment,” NOAA San Francisco Bay Watershed and Database Mapping Project, available at http://response.restoration.noaa.gov/cpr/watershed/sanfrancisco/sfb_html/sfbenv.html.

[29] Henry Noyes Journal, pp. 11-28, 35-47, 49, 51-63, 85-98. The summaries list total proceeds and hunting partners for each year from 1850-1851 through 1854-1855 and again in 1860-1861. See ibid. p. 325.

[30] Ibid. p. 90.

[31] Compare, e.g., ibid. pp. 36 ($9.00 on Sept. 24, 1856) and 95 ($7.50 on Dec. 6, 1859) with p. 16 ($162.75 on Nov. 13, 1855).

[32] Ibid. p. 325

[33] See, e.g., ibid. pp. 30, 95-96.

[34] Genealogical and Biographical Record, p. 720; “Had a Varied Career.”

[35] Henry Noyes Journal, pp. 64, 85, 91.

[36] Salmon Fishing Agreement, Aug. 4, 1860, Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 16, LHSA. See also Letter from William F. Walton & Co. to Henry Noyes, Enoch Noyes, Jr., and Judson Baldwin, San Francisco, Sept. 22, 1860, Noyes Papers Box, Noyes Correspondence files, Item 18, LHSA (concerning performance of the fishing contract and also asking the Noyes brothers and Baldwin to send wood suitable for making barrels).

[37] See Henry Noyes Journal, p. 325.

[38] Genealogical and Biographical Record, p. 720; “Had a Varied Career.” Noyes bought the 228-acre farm on December 8, 1863, for $8,000.00, paying one-third then and the rest, secured by a bond, on April 8, 1864. Bond from Henry Noyes and William Noyes Ely, Dec. 8, 1863, private collection.

[39] Henry Noyes Journal, p. 224.

[40] Norwich Bulletin, June 28, 1917, p. 6.