by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: Matilda Browne, Untitled [Yellow House with Roses], after 1918. Private collection. Shows the house on today’s Lyme Street purchased in 1819 by Dr. Sylvester Wooster

“News! news! I have great and wonderful news to tell you but it is so long since I have written that I hardly know how to begin,” Phoebe Griffin Lord (1797-1875), then age 17, wrote from Lyme to her older sister Harriet Lord (1795-1882) in Boston. The letter, dated November 11, 1814, opened with details about a friend’s wedding, then shifted to the “new doctor just arrived in town.” She reported having “the honor of seeing him [the] past evening at Mr. Rockwell’s,” a reference to the home of Lyme’s minister nearby, and described the unmarried new doctor as a neighbor. “He came well recommended,” she added, and had support from the town’s most prominent family. “The Griswolds intend to patronize him,” Phoebe wrote.[1]

House on today’s Lyme Street where Rev. Lathrop Rockwell entertained the town’s new doctor in 1815, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Dr. Sylvester Wooster (1790-1825), age 24, grew up in Huntington (later Shelton), north of Milford where his family members were among the Connecticut colony’s early settlers. He was recommended to Lyme families by Dr. Thomas Miner (1777-1841), a Yale graduate who settled in town in 1808, “upon the solicitation of Governor Matthew Griswold and other gentlemen.” Two years later Dr. Miner married Phoebe Mather (1772-1811), daughter of the town’s wealthiest merchant, and practiced medicine in Lyme for four years. He then returned to his native Middletown, prompted in part by the death of his wife and infant child.[2] The eligible Dr. Wooster who succeeded him, and whom Phoebe Lord described as one of Lyme’s “beaux,” married in 1818 Louisa Hayden (1801-1841), niece of Essex shipbuilder Uriah Hayden (1770-1801). The next year Dr. Wooster purchased a house with barn and shop on the “highway” through Lyme, a property that impressionist artist Matilda Browne would purchase a century later.

House on today’s Lyme Street where Dr. Sylvester Wooster established a medical practice. Postcard, ca. 1905. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

Six months after arriving in Lyme, Dr. Wooster had advertised in the Connecticut Gazette on June 6, 1815, his availability to vaccinate with “Kine Pock,” a still controversial inoculation that prevented the deadly disease of smallpox.[3] He became a member of the New London County Medical Society the same year and in 1823, with his local practice well established, took as his apprentice Christopher E. Hill (1803–1874), son of Lyme shipyard owner Edward Hill (1774—1828).[4] The next year Dr. Wooster had sufficient means to purchase from Christopher Hill’s father three additional acres of land north of his home on the “town street.” A “prevailing fever” claimed the life of Dr. Wooster, age 35, in 1825.

In a detailed account of the typhus epidemic that year, Dr. Miner reported that “the mercury stayed between 90 and 94 degrees for several hours each day in July in the rooms of the sick.” What he called the New England Sinking Fever raged during “the hottest season ever known in this climate” and “proved very fatal to the medical profession.” Five other physicians besides Dr. Wooster died in nearby towns in the “almost unparalleled” outbreaks of typhus in 1823 and 1825.[5] An article in Lyme’s Sound Breeze newspaper would later state that the actual cause of death for Dr. Wooster and others in 1825 was the excessive bloodletting employed by the doctors of the day.

“Robert McCurdy (1800-1880) is dangerously sick with the typhus fever,” Harriet Lord wrote to her sister Julia in November 1823. The disease, Dr. Miner reported in a published pamphlet, had prevailed in about a dozen towns in the Middletown area, with some 360 cases under his care. He found that in severe cases “opium was the most important remedy” and was “regularly administered from the very first visit.” Moreover, “the whole of those patients, whose symptoms were promptly met with opium, invariably recovered.” He also reported that “alcohol was highly beneficial in some cases, and required to be employed freely in many,” and stated that for milder cases, camphor, ammonia, peppermint, and other essential oils were occasionally beneficial. The early use of hot baths “was of great service,” with the water as hot as could be borne, as was the application of plasters, often to the forehead, “to the blistering point.”

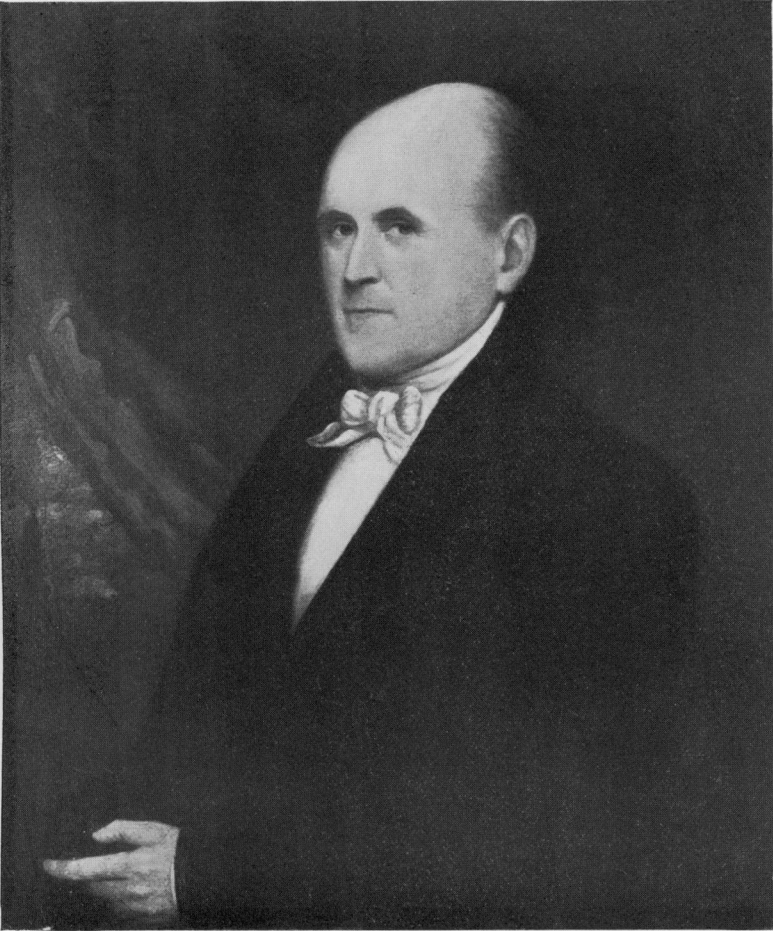

Thomas Hanford Wentworth, Dr. Thomas Miner, ca. 1836. Oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery.

When Dr. Miner differentiated “sinking fever” from common typhus, he highlighted not only “the early paroxysms of sinking” but also “the great effect which opium had in mitigating all the dangerous symptoms of every stage, but more especially, irritability, delirium and coma.” His published findings were quickly challenged. Dr. Benjamin Catlin (1801-1880), a respected physician in nearby Meriden, countered that “many physicians in Connecticut, and some in Middletown and vicinity, doubted whether any such fever as that described by Dr. Miner prevailed in that vicinity except what was caused by his peculiar treatment.” Dr. Catlin argued that the reliance on opium had “led to much bad practice, and that in some cases the peculiar symptoms resembling sinking typhus were really due to excessive doses of opium.”[6]

Louisa Wooster’s demeanor after her husband’s death led to speculation among her “down street” neighbors about her apparent effort to attract suitors. Harriet Lord observed in a family letter in 1826 that Louisa “looks quite belle-like” and the next year remarked that Mrs. Wooster, “who is really a sweet looking very pretty woman,” had become “a good deal of a belle among the married men & bachelors.” Attorney Henry Matson Waite (1787–1869), also a “down street” neighbor, assumed guardianship of Mrs. Wooster’s two children in 1827 as well as a mortgage on her property. The next year she married prominent New York physician Ebenezer Storer (1803-1882). Her home along the “turnpike road” then changed owners four times before Justin M. Smith (1812-), a farmer and machinist from East Haddam, purchased the four-acre plot with dwelling house, barn, shop, and other buildings in 1854.

Town of Old Lyme, ca. 1855, showing the location of Justin Smith’s house where Dr. Sylvester Wooster had a medical practice and also the house of Dr. Richard Noyes, LHSA.

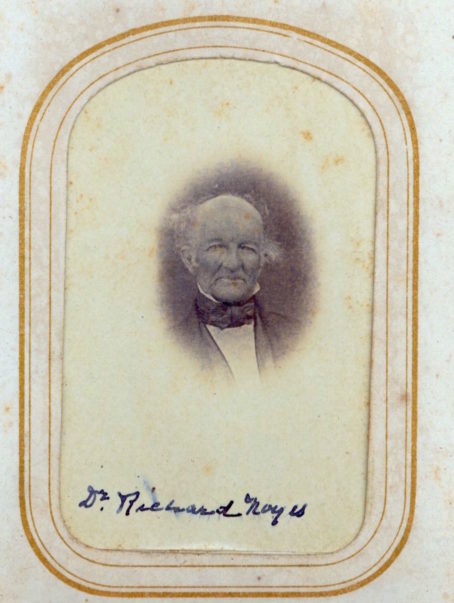

A steady outflow of residents seeking land and opportunity in prospering locations like Ohio brought repeated property turnovers in Lyme after 1820. The town’s population dropped from 4,069 that year to 2,663 in 1850. Among the residents who had “gone west” was Dr. Christopher Hill, who attended Yale Medical College after apprenticing with Dr. Wooster and by 1837 had established a medical practice in Cleveland. Dr. Richard Noyes (1787-1864), a descendant of Lyme’s first minister, followed Dr. Wooster in providing medical care for Lyme families. Dr. Noyes is said to have practiced medicine in his native town for forty years.

Dr. Richard Noyes, LHSA

[1] Phoebe Lord to Harriet Lord (November 11, 1814). Ludington Family Collection.

[2] Frank K. Hallock, “Thomas Miner, M.D. of Middletown: An Early Connecticut Physician of Exceptional Culture,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (1936), p. 345.

[3] H. Carrington Bolton, “Memoir of Dr. Elisha North,” Proceedings of the Connecticut Medical Society (Hartford, 1884), p. 159.

[4] H. Hamilton Hurd, History of New London County, Connecticut (Philadelphia, 1882), p. 61; Harriet Lord to Julia Ann Lord (November 3, 1823), Ludington Family Collection.

[5] “Miner on Typhus Syncopalis,” in New York Medical and Physical Journal (New York, 1825), 4:544-555.

[6] Charles B. Graves, M.D., “President’s Address: Epidemic Diseases in Early Connecticut Times,” in Proceedings of the Connecticut State Medical Society (New Haven, 1920), pp. 93, 95.