by Caroline Fraser Zinsser, Ph.D.

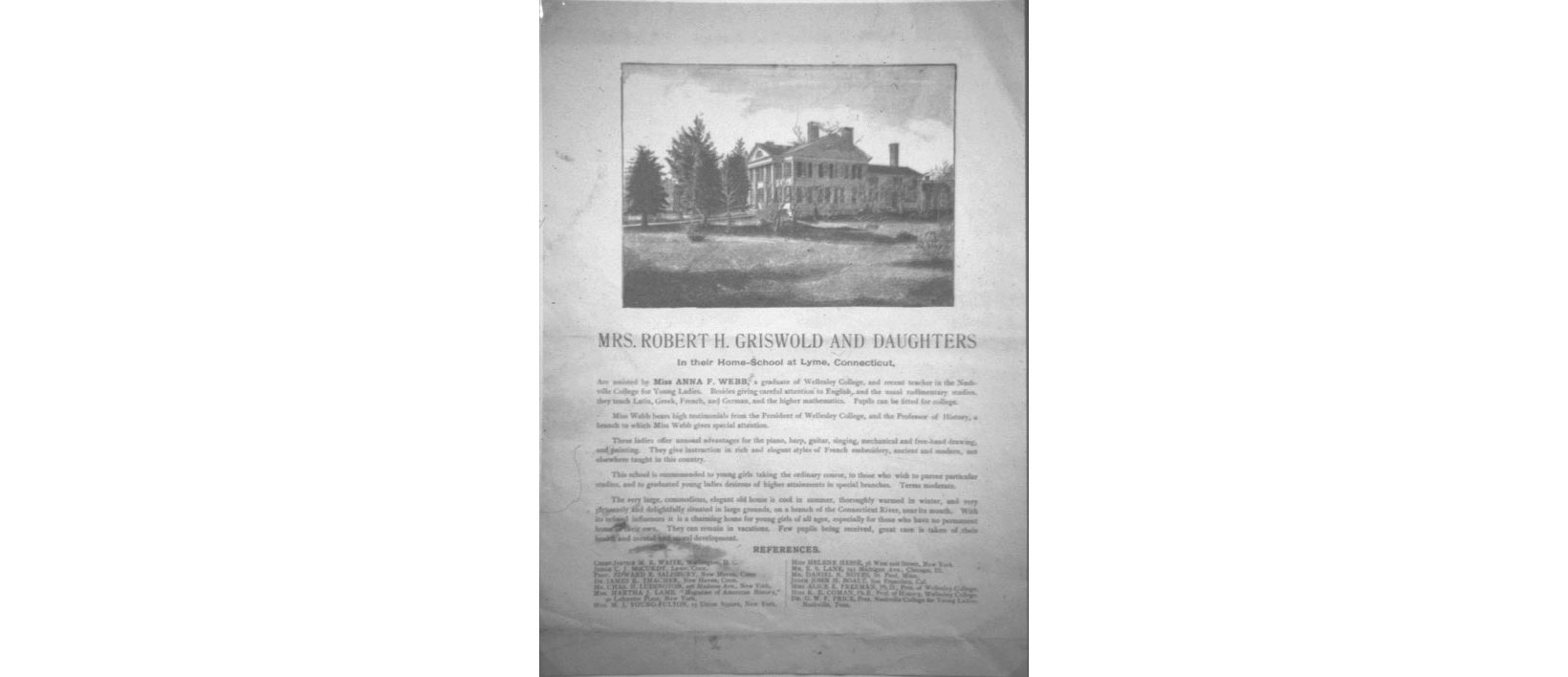

Featured Photo (above): Griswold Home School circular, 1878.LHSA

Although Florence Griswold’s unique role in the history of American art has been well documented, we have known surprisingly little about her life as head of the Griswold Home School, an educational institution which preceded the arrival of her artist boarders and occupied the four women of the Griswold family for fourteen years from 1878 to 1892. But by tracking newly uncovered historical sources, we now know much more about the workings of the school and about Florence Griswold in her position of school administrator.[1]

Florence Griswold, ca. 1880. LHSA

The Home School was launched amid the great changes in the education of American women that took place in the 19th century. Historically, young women were educated differently from men. Since they were excluded from the professions, there was no need for them to study advanced subjects as preparation for colleges that would not admit them. Instead, girls were taught what were referred to as “accomplishments” or “ornamentals”—needlework, music, dancing, and art—to prepare them for lives as wives and mothers. But during the 19th century increasing numbers of pioneering reformers argued for women’s rights to an education equal to that of men.

Students at the Griswold Home School, ca. 1885. LHSA

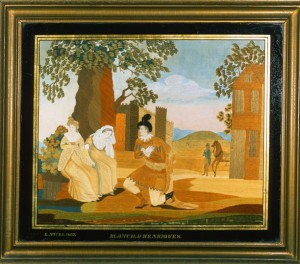

Schools teaching “accomplishments,” however, did not see themselves as offering an inferior education. Their aim was to provide training, solidly based on historical precedent, for becoming women of refinement—of artistic sensibilities, discriminating taste, social skills, and a moral integrity that would enable them to assume an honored place in the social structure of the time. This much-admired traditional education did not die easily.

Eunice Noyes, a schoolgirl from Lyme, created Blanch & Henriques at Mrs. Lydia Royse’s school in Hartford. Silk embroidery, 1807. Private Collection

In the end, academics won out over ornamentals. Women fought for and won the right to the kind of education that had for centuries been limited to men only. But at the time the Griswold Home School was launched, the shift to a male model of secondary schooling as preparation for universities had not been completed. Girls’ education was in a state of flux, and took the form of a patchwork of academies, seminaries, preparatory schools, institutes, boarding and day schools, and home schools, each offering different combinations of academics and accomplishments.[2]

Griswold family home, ca. 1885. LHSA

Ellen Noyes Chadwick. Courtesy Werneth Noyes collection

How did the Griswold Home School fit into this progression toward what we now consider modern education for women? Here is how the school appeared to Mrs. Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824-1900), one of the leading matrons of Old Lyme, when she enrolled her thirteen-year-old daughter at the school’s opening in 1878. In a letter to her son Mrs. Chadwick wrote:

“Bertha commenced school with Florence this morning and she likes going. It is very pleasant. Florence has taken the north front room and fitted it up for a schoolroom. She has but five scholars. I send you this her circular—perhaps you may influence someone to come—for Florence cares more, I think, to have a boarding school than a day school. I think it is a desirable place in regard to health and comfort and if Florence teaches the ordinary branches with French; Louise music and Adele painting and drawing, the course seems quite complete.” [3]

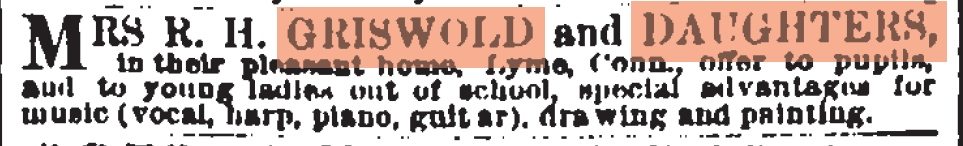

Griswold Home School advertisement, New York Herald-Tribune, October 16, 1881.

Although the school would be formally referred to as that of “Mrs. Robert H. Griswold and Daughters,”[4] Mrs. Chadwick sees it as Florence’s. We can only speculate on the many family discussions that had led the Griswolds to open their house to paying students. But it appears that Florence, though the youngest member of the family, is running the school.

Robert H. Griswold (1806-1882) would, of course, still be considered the head of the household, but family finances had floundered since his prosperous days as a packet ship captain. In failing health, he had begun to sell off his land, and by 1877 there were three mortgages on the remaining property. In these straitened circumstances, it was up to the four women, his wife Helen and their three daughters, to save the situation. In a valiant effort to forestall financial crisis, they optimistically counted on their combined talents as sufficient, and their house as commodious enough, to ensure the success of a home-based day and boarding school for girls. [5]

Thomas Coke Ruckle, Captain Robert Harper Griswold, 1840. Watercolor on paper. FGM, Gift of Dr. Matthew Griswold.

Helen Powers Griswold (1820-1899), Florence’s mother, would act as housekeeper but also had to care for her ailing husband, who died four years after the school opened. Like her daughters, she was talented. One of her nieces remembered that at family gatherings “we used to dance through long afternoons, Aunt Helen playing the piano.” [6] She had also dared to travel with her older children on ocean crossings with their captain father, [7] journeys that would have widened their horizons beyond the confines of their New England town.

Helen Powers Griswold. LHSA

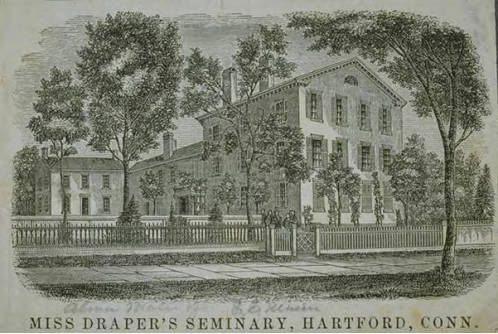

Miss Draper’s Seminary, Hartford, Connecticut. Courtesy Connecticut Historical Society

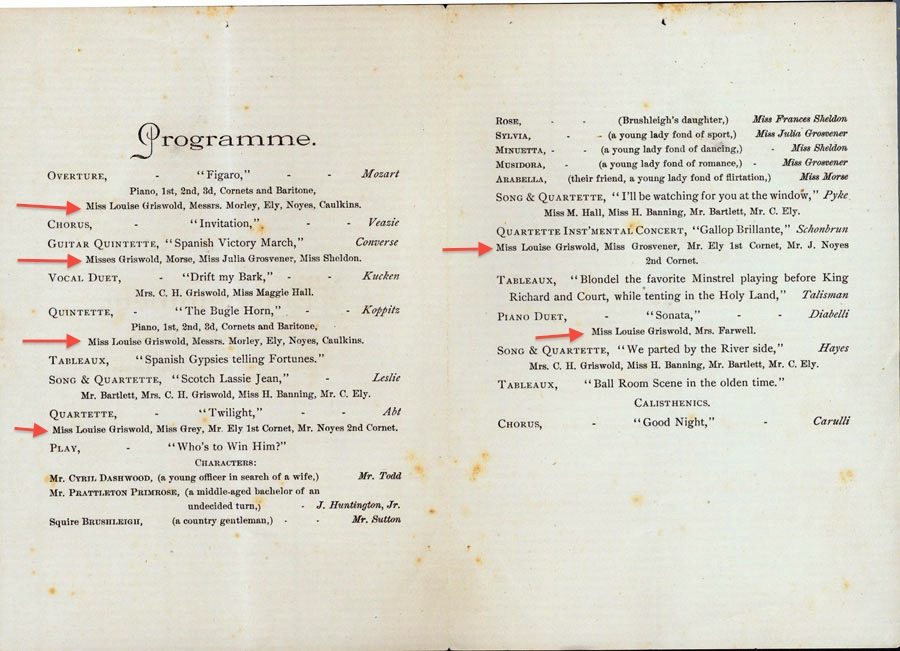

Louise (1842-1896), the oldest sister, was known for her “merry laugh,” “cheerfulness,” and many friends. At age 16 she had been sent to Miss Draper’s Seminary in Hartford, where she most probably studied music. [8] A noted local pianist, organist at the Congregational church for more than 20 years, and piano teacher of many pupils, she was affectionately known by all, even by children, as “Miss Lou”—a promising background for attracting students. [9]

Entertainment, Lyme, Conn., June 10, 1889. LHSA

Nathan Pond to Martha [Pond], October 28, 1892. LHSA

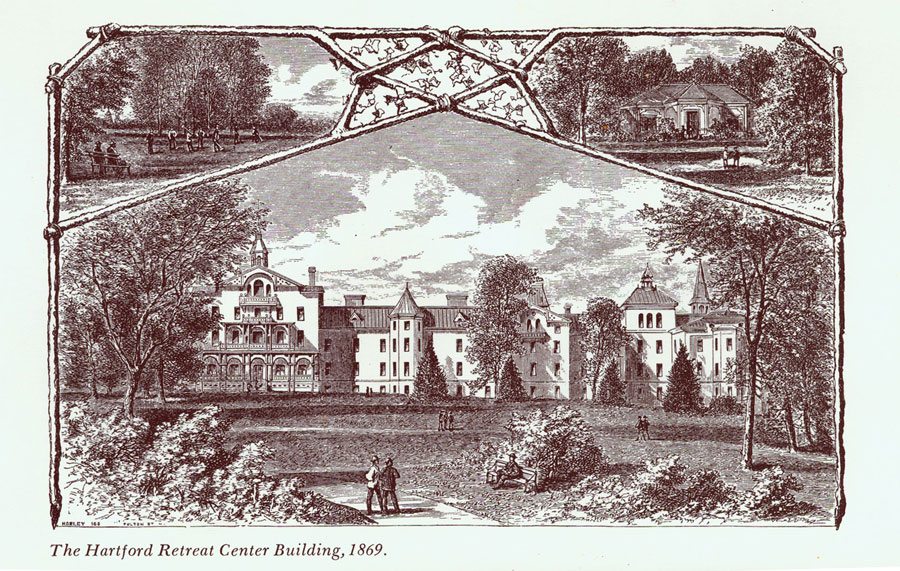

Adele (1845-1913), next in line, remains a shadowy figure. She was an artist—or perhaps what we might label “artistic.” In the town’s centennial exhibition in 1876, she was represented by “a collection of pebbles painted by the seashore, two landscapes, and a painted glass jewel case.”[10] At the school she specialized in painting china and what was termed “elegant foreign embroideries.”[11] In 1883, perhaps to further her skills as a teacher, she took art “lessons” in New Haven.[12] Though she was confined to the Hartford Retreat for the last thirteen years of her life, her death certificate noted her occupation as “school teacher.”[13]

Florence, like her sisters, was conservatively educated. She had attended Lyme’s District #1 public grammar school, then continued on at a private school in New London run by her older Griswold cousins Lucretia and Caroline Perkins.[14] Here she was taught music, languages, embroidery, painting, and became proficient in piano, harp, and guitar—the traditional “accomplishments” of a dutiful daughter.[15]

The Hartford Retreat, 1869. Frances J. Braceland, The Institute of Living (1972).

There is no evidence of Florence’s particular mastery beyond the “ordinary branches” of reading, writing, and arithmetic, into the advanced study of literature, science, history, or math, much less to her abilities in the many details of administration required for running a school. But in the 1880 census, the Griswold family was recorded as Robert H. Griswold, age 73, head of household; Helen, age 59, keeping house; Louise, age 38, Music Teacher; Adele, age 36, Artist; and Florence, age 29, School Teacher. The Griswold women had successfully transformed their home into a school.

Florence Griswold, ca. 1870. LHSA

[1] This account of the Griswold Home School was originally prepared for a presentation to the Florence Griswold Museum docents, August 27, 2012. Carolyn Wakeman provided invaluable assistance in research and advice during my study of Miss Florence’s school. A letter from Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Charles Noyes Chadwick, September 23, 1878, establishes the beginning of the school. The New-York Tribune, August 21, 1891, appears to have published its final advertisement. The memorial booklet for Louisa Augusta Griswold (1896) states that the school was opened in the Griswold house “in the Fall of 1878 and continued fourteen years.”

[2] For the history of the early education of American women, see, for example, Margaret A. Nash, Women’s Education in the United States, 1780-1840 (New York, 2005); Mary Kelley, Learning to Stand & Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Durham, N. C., 2008).

[3] Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Charles Noyes Chadwick, September 23, 1878, Lyme Historical Society Archives (LHSA). Anna Bertha Chadwick Trowbridge (1866-1940) would later edit, with Charles McLean Andrews, Old Houses of Connecticut (New Haven, 1923).

[4] New-York Tribune, April 17, 1880.

[5] Laurie Bradt, “Keeper of the Artist Colony: The Life of Florence Griswold (1850-1937), unpublished manuscript (2002), p. 7. LHSA.

[6] Charles Brush Perkins, Ancestors of Charles Brush Perkins and Maurice Perkins (Baltimore, 1976), p. 244.

[7] Helen Powers Griswold to Caroline, January 23, 1841; Robert Griswold to E[benezer] Lane, his brother-in-law, May 10, 1847; Julia Powers to Helen Powers, April-July, 1851; photocopies, Lane Collection, LHSA. Also see Bradt, p. 3.

[8] Josephine Noyes to Caroline Noyes Kirby, September 9, 1858. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[9] Bradt, p. 8.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Griswold Home School advertisement, New-York Tribune, April 2, 1889.

[12] Helen Griswold to Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, dated “Thursday” and likely written in 1883. Transcript courtesy Carolyn Wakeman; Old Lyme Historical Society collection.

[13] In 1900 when Florence started receiving artists as boarders in her family home, she petitioned the local probate court for permission to commit her older sister to the Connecticut Retreat for the Insane in Hartford. The cause of Adele’s death at age 68 was “cerebral hemorrhage.” See Bradt, p. 17. Certificate of death, photocopy, LHSA.

[14] School lists, LHSA. Also see Bradt, p. 16.

[15] See Perkins, p. 111; Bradt, pp. 18-19.