by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Photo (above): Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Samuel Mather House, ca. 1885. LHSA

Margaret Mather (1787–1866), called “Peggy” by her family and in Lyme’s birth records, moved to Albany when she reached the marriageable age of 21. Just half a year after she became the wife of William Nicoll Sill (1786–1844) and settled into a grand brick mansion house overlooking the Hudson River, her father died in Lyme, leaving each of his nine children a substantial bequest. Samuel Mather, Jun. Esq., (1745–1809) was then the town’s wealthiest merchant.

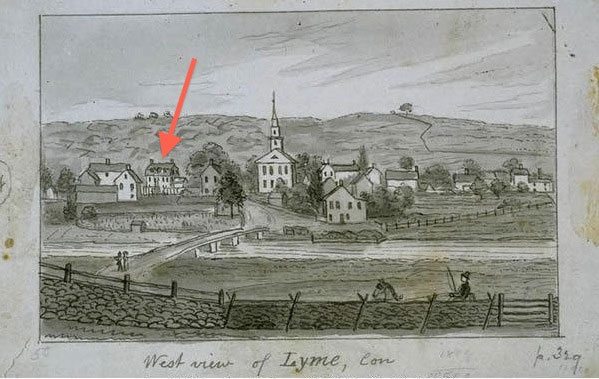

John Warner Barber, West View of Lyme showing Samuel Mather house, 1838. Courtesy Connecticut State Library

Mather Family in Lyme

Samuel Mather’s fortune accumulated between America’s two wars with Britain. The first of fifteen vessels he commissioned from the Hill shipyard on the Lieutenant River was a 79-ton schooner named “Peggy,” designed for the West Indies trade and launched in 1784.[1] When he died, his property included land holdings, promissory notes, and bank shares in addition to his house (now the First Congregational Church parsonage) and the extensive stock of merchandise in his four stores. The itemized inventory of his estate, valued at $79,612.61, fills 32 pages.[2]

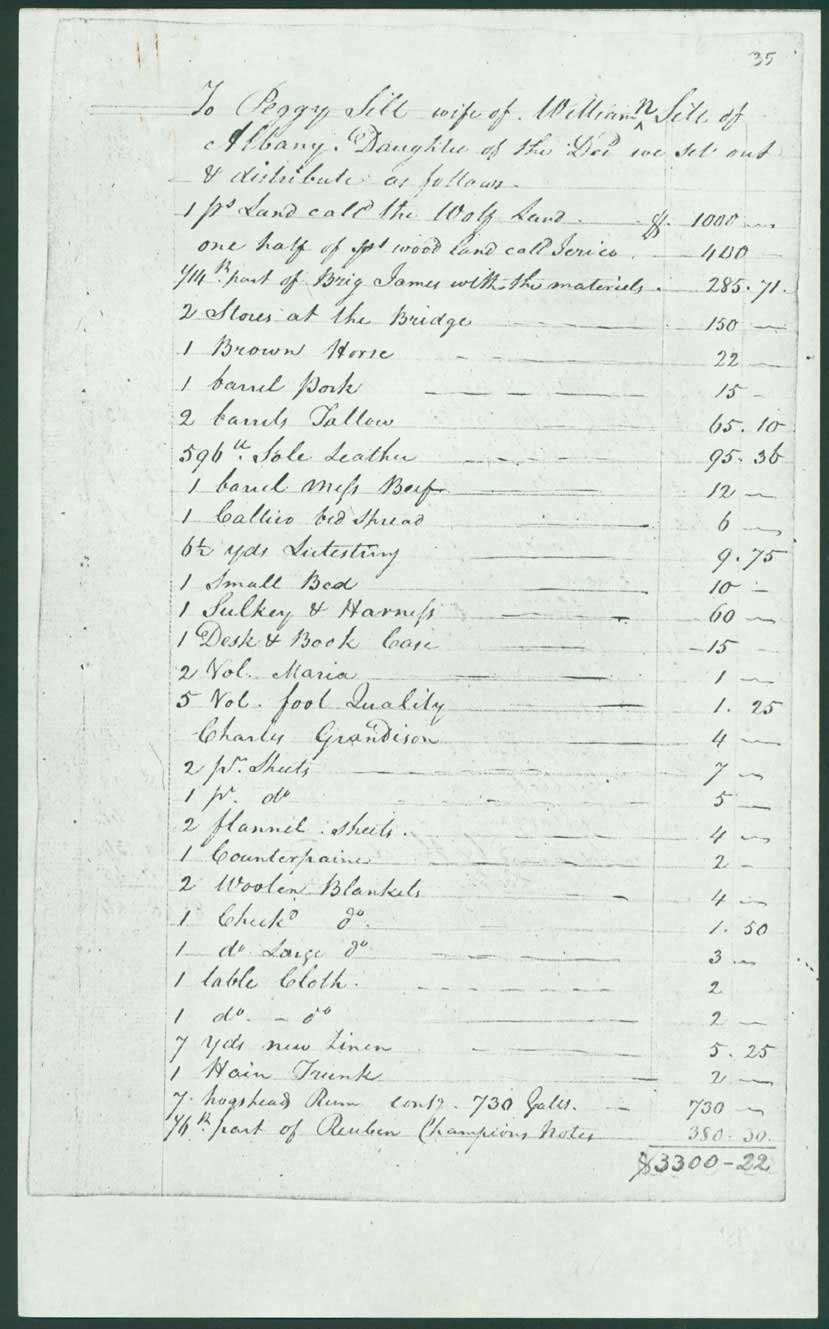

Distribution to Peggy Sill from Samuel Mather’s estate inventory, 1809. LHSA

In 1809 the family home passed to Mather’s third son James who continued to reside in Lyme after his two older brothers had moved to Albany. Like her siblings, Peggy received property valued at $8,845 from her father’s estate. The distribution “To Peggy Sill wife of William N Sill of Albany” included: “1 ps Land calld the Wolf Land ($1000),” “7 hogshead Rum contg 730 Galls ($730),” “Lebeus Pecks note ($430),” “one half of ps wood land calld Jerico ($400),” 1/14th part of Brig James with the materiels ($285.71),” and “2 Stores at the Bridge ($150).”[3]

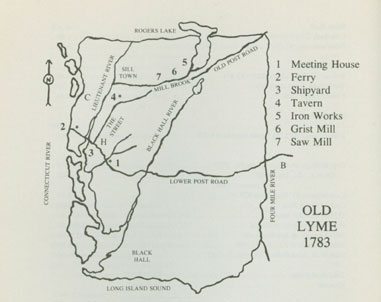

Map of Lyme, 1783. Susan Hollingsworth Ely, The Parsonage, p. 72.

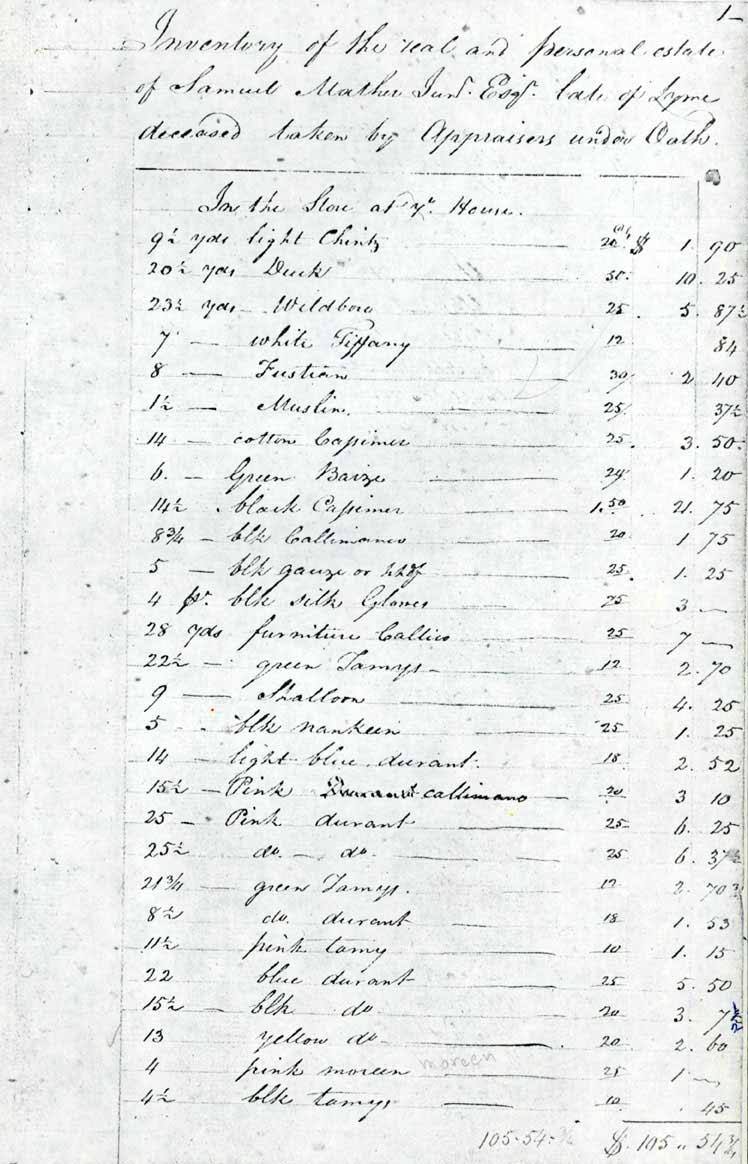

The itemized list of Mather’s estate illustrates the comfortable surroundings Peggy left behind when she moved away from her family, but it also displays the range of consumer goods available in Lyme before the War of 1812. Along with lumber, hardware, cookware, farm implements, and sturdy cloth used for bedding and daily apparel, the store located at the Mathers’ house stocked luxury items like exotic teas from China and an array of fine imported dress-making fabrics. Silks, satins, cambrics, and embroidered tamboured muslins appear on the inventory, along with laces and ribbons for trimming, and black gauze for veils.

The store also stocked ladies’ accessories like pocket books, handkerchiefs, gloves in silk and leather, and stockings in worsted and cotton. Shawls came in a selection of fabrics and colors for different occasions; seventeen of the 31 shawls in stock were purple. “Surely Mrs. Mather and her daughters were among, if not the most, fashionably and expensively dressed ladies in Lyme,”[4] commented local historian Susan Hollingsworth Ely.

Estate Inventory of Samuel Mather listing stock of fine fabrics, 1809. LHSA

Mather Family in Albany

Peggy’s eldest brother Thomas Mather (1768–1849) was among the Hudson Valley’s earliest New England migrants. In 1792 he joined other investors to launch a glass works near an expanse of sandy soil northwest of Albany. The company prospered as the demand for window glass grew,and three years later Thomas Mather became the principal owner. His younger brother Samuel Mather (1771–1863), after graduating from Yale and clerking for a year in his father’s store, also became a partner in the Albany glass works, which in 1795 was renamed Thomas Mather & Co.[5] Albany’s population then totaled 6,000 inhabitants, of whom 2,000 were slaves.

Mold-blown flasks made at the Albany Glass Works, ca. 1810. Albany Institute of History & Art collection

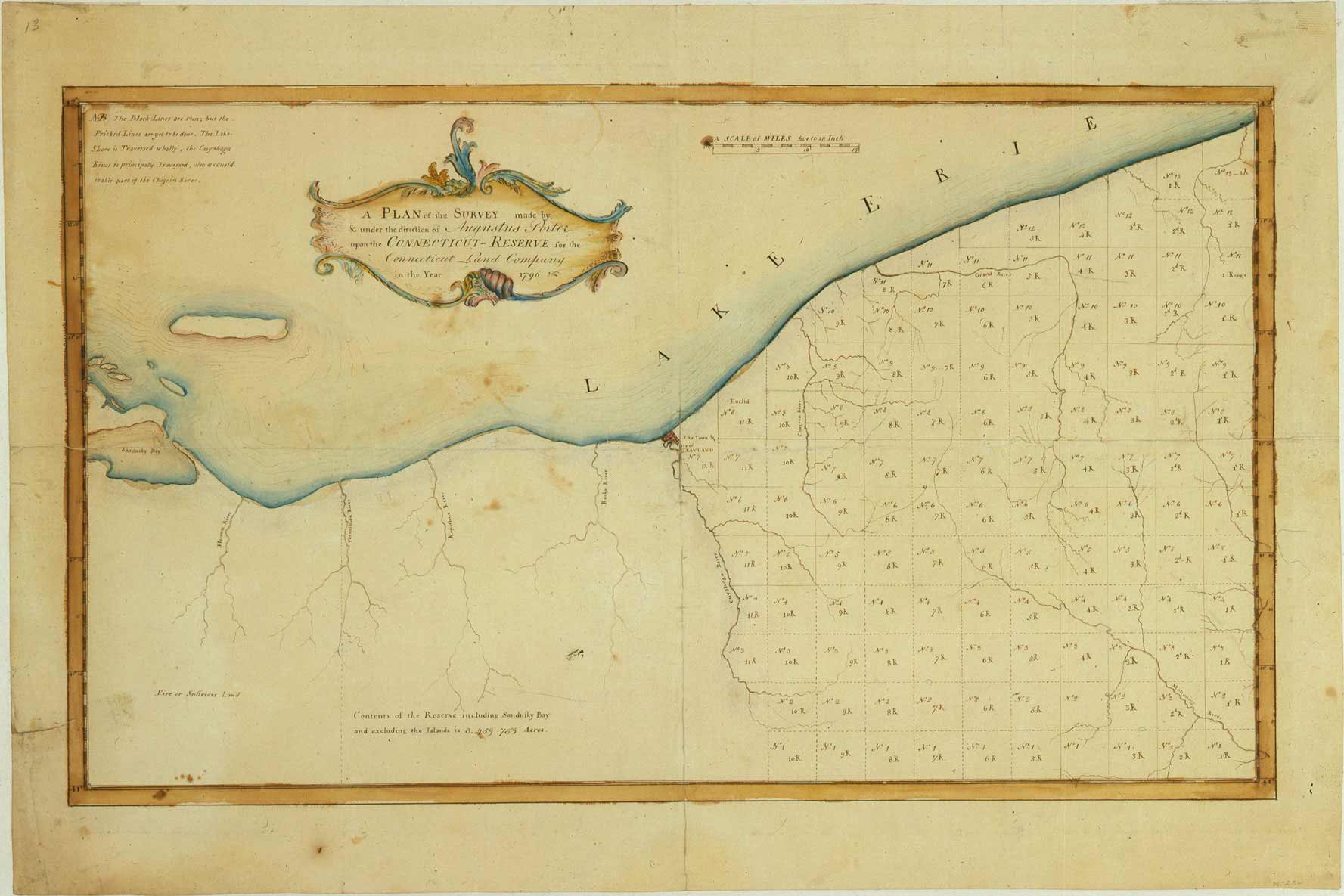

That same year their father in Lyme joined a group of wealthy investors to form the Connecticut Land Company, which owned a vast stretch of wilderness south of Lake Erie called the Connecticut (or Western) Reserve. After Samuel Mather contributed $18,461 to the syndicate’s land purchase, his sons in Albany, with their father’s financial backing, also invested. Thomas, by then a mill owner, provided funding and supplies for a second survey team sent to measure and divide the wilderness tract in 1797. Samuel, who became a shareholder and was not yet married, traveled for months on horseback to inspect the Mathers’ land in the Western Reserve and assess its value.[6]

Map of the Connecticut Reserve, detail, 1796

Not long after their father’s death the Mather brothers, by then wealthy themselves, moved back to Connecticut and settled in Middletown, still a prosperous river port. For a few years they engaged in the declining West Indies trade, while Peggy, alone of the Mather children, remained in Albany.

Samuel Mather house, Middletown, now the Middlesex County Historical Society, Middletown

Thomas Mather house, Middletown

Sill Family in Albany

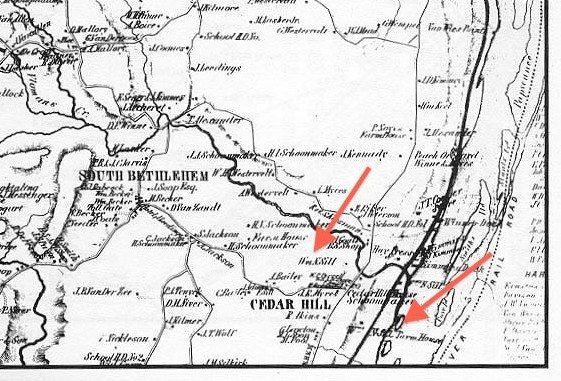

Unlike her childhood friend and sister-in-law Abigail Noyes Sill, Margaret prospered after her marriage. William Sill not only managed the 1,300-acre estate called Cedar Hill that he later inherited from his grandfather Col. Francis Nicoll (1737–1817) but also served as a Bethlehem town supervisor, an Albany county judge, and a member of the New York state legislature.[7] The Sills had eight children who all married well.

Bethlehem House, 1860. Duncan H. Sill Papers, New York Historical Society

John Wilkie, Portrait of Margaret Mather Sill, age 2 years 7 months, 1840. Courtesy Bethlehem Historical Society

With commercial traffic increasing on the Hudson River, Margaret’s husband built a dock, warehouse, and store to establish their eldest son Rensselaer Nicoll Sill (1811–1864) in business.[8] A portrait of her granddaughter Maggie Sill (1837–1881), painted by John Wilkie in 1839, preserves an image of her namesake. She was then 59 when her husband died in 1844 and she inherited by will the large Hudson River estate.

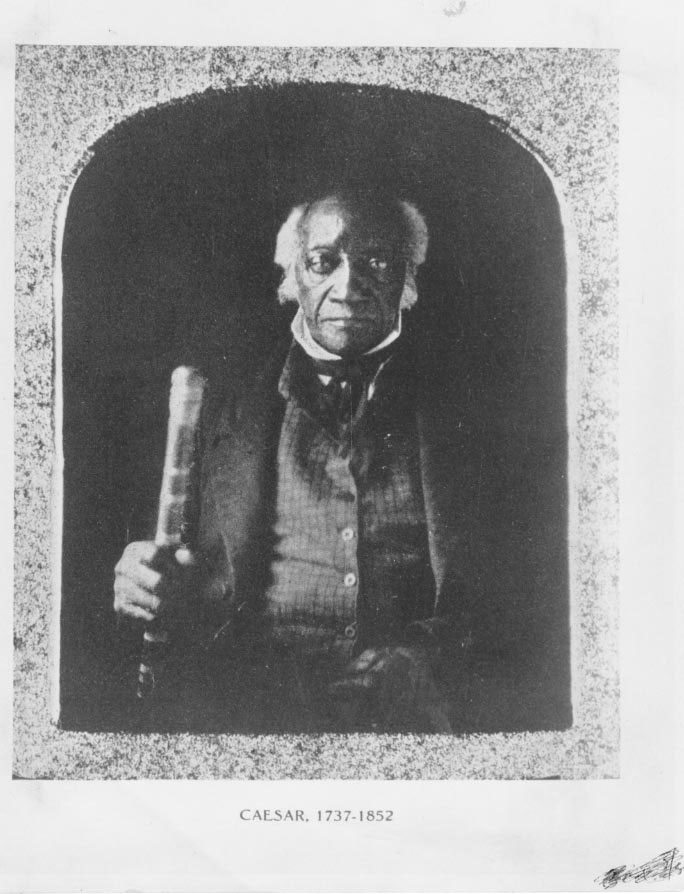

Included with that property was a 107-year-old slave named Caesar (1737–1852) who had served six generations of the Nicoll-Sill family. Said to be the last person enslaved north of the Mason-Dixon line when he died eight years later, Caesar had raised his own children, born into slavery, on the Cedar Hill estate. A Sill family memoir stresses the bonds of affection and loyalty that tied him to his first master’s descendants. In 1851 they persuaded him to pose for a daguerreotype portrait.[9]

Cedar Hill map showing house of Wm N Sill and riverfront Town House of Rensselaer Sill, 1854

Caesar Nicoll, 1851

Not far from the stone that marks Caesar’s burial place in the Nicoll-Sill cemetery, a simple marker commemorates the woman from Lyme who was his last owner: “Margaret Mather, d. May 1, 1866, 77 yr.”[10]

Gravestones, Cedar Hill cemetery, 2005

[1] Susan Hollingsworth Ely and Margaret Wellington Parsons, The Parsonage: First Congregational Church, Old Lyme, Connecticut (Old Lyme, 1983), p. 15.

[2] Samuel Mather estate inventory, photocopy, Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 5, LHSA; Ely, pp. 63-6. The original inventory is preserved at the Connecticut State Library, Probate Estate Papers, Case No. 3503.

[3] Mather estate distributions, LHSA.

[4] Ely, p. 35.

[5] Jonathan Tenney, New England in Albany, (Boston, 1883), p. 24. Joel Munsell, in The Annals of Albany (Albany, 1853), p. 231, describes Albany in 1795: “Some manufacturies have been established at a small distance from the town, among which is a glass house, in which both window glass and bottles are made. The former is pretty smooth, and the manufactory is carried on with much activity.” When Munsell notes Albany’s slave population, he remarks that “the laws of the State of New York permit slavery,” Ibid., p. 230. George R. Howell and Jonathan Tenney, in History of the County of Albany, N.Y. (New York, 1886), p. 76, state that the glass works turned out 500,000 feet of window glass annually at one period, before it was discontinued in 1815 “for want of a suitable supply of sand and fuel.” A biographical sketch of Samuel Mather appears in Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Sketches, Graduates of Yale College (New York, 1911), p. 32.

Also see: Claude M. Shepherd, The Connecticut Land Company: A Study in the Beginnings of the Western Reserve (Cleveland, 1916), p. 73; Harriet Taylor Upton, History of the Western Reserve (Chicago, 1910), pp. 715 ff.; Richard Buel, Jr., The Peopling of New Connecticut (Hartford, 2011), pp. 30-1. In 1798 Samuel Mather wrote from Youngstown to his father in Lyme: “I am much disappointed in the prospect of speedy settlement upon the Lake—Butt few inhabitants have come on this Season, and those few are poor and inactive. . . .I have been on all your Land upon the Lake, and am more pleased with No.12 in the 2nd [Sheffield] than the average town. The Land on this Town is rich, but very heavey timbered and hard to make a beginning.” See Gladys Haddad, “Early Western Reserve Impressions: The Surveyor, the Artist, the Land Speculator,” p. 5.

[7] George G. Sill, Genealogy of the Descendants of John Sill (Albany, 1869), pp. 23-4.

[8] A letter from W. J. Thome to William Sill, dated January 2, 1836, and preserved in the Duncan H. Sill Papers at the New-York Historical Society, notes that Rensselaer Sill’s trading firm dealt in oats, rye, and stone. See also the National Register of Historic Places’ description of the two-room Cedar Hill Schoolhouse, built just east of the Nicoll-Sill House

[9] Duncan H. Sill, “Biography of a Slave,” 1929, unpublished ms. in Duncan H. Sill Papers, New-York Historical Society. For a critical view of the Sill family’s slave ownership, see “Caesar Nicoll: A Biography of an Enslaved African,” in L. Loyd Stewart, A Far Cry from Freedom: Gradual Abolition, 1799–1827 (New York, 2005), pp. 23-4.