by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Photo (above): Phoebe Griffin Noyes, Phebe Lord (detail). Watercolor on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Townsend and Jane Ludington

The War of 1812, whose 200th anniversary is being commemorated this year, brought the threat of attack to Lyme’s shores. Letters to Phebe Griffin Lord (1768-1841) from her brother in New York reveal how wartime conditions affected a local family.

George Griffin, Jr., to Phebe Lord, November 16, 1812. LHSA

Educating Daughters

The death of Joseph Lord (1757-1812) on March 15, 1812, left his wife Phebe Griffin Lord with seven daughters to raise and a 200-acre farm to manage along what is now Lyme Street. Phebe, then 44, was expecting their eighth child.

In her youth Phebe had acquired artistic skills from her mother Eve Dorr Griffin (1733-1814), who studied needlework in Boston, and a love of learning from the rigorous tutors who prepared her brothers for Yale.[1] Determined that her own daughters would become educated women, the Widow Lord, as she became known, kept her eldest child Harriet at home to help with the household and the infant named Josephine. But she sent her second child and namesake, then fifteen, to live with her brother George Griffin, Jr. (1778-1860), who practiced law in New York. There young Phebe Lord (1797-1875) could receive schooling not available to girls in Lyme.

Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Joseph Lord house, ca. 1885. LHSA

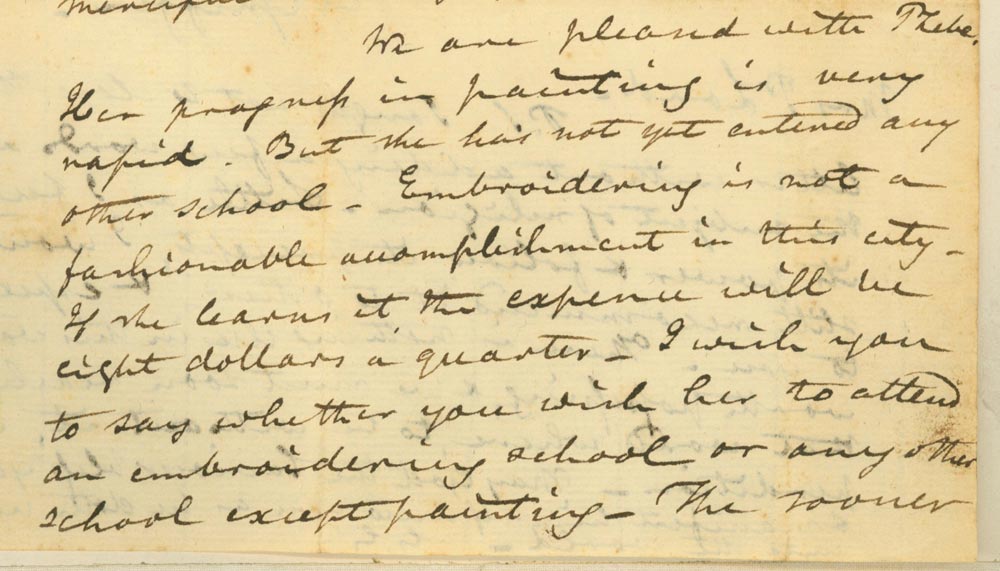

On November 16, 1812, George wrote of his niece’s progress:

Dear Sister,

. . . .We are pleased with Phebe. Her progress in painting is very rapid but she has not yet entered any other school. Embroidery is not a fashionable accomplishment in this city. If she does it the expense will be eight dollars a quarter. I wish you to say whether you wish her to attend an embroidery school or any other school except painting. The sooner we have your determination on this subject the better.

. . . . With regard to what is best for Phebe, I am at a loss. You must decide for yourself, and that decision must depend in a great measure upon what you think will be most useful to her in Connecticut. At all events, you must let us know your determination without delay.

In haste, Your affectionate brother, G Griffin[2]

Wartime Blockade

In response to continuing British harassment of American shipping, President Madison signed a declaration of war on June 18, 1812. The second war with Britain, which crippled New England’s maritime trade, was so unpopular in Connecticut that Governor Roger Griswoldfrom Lyme refused to allow the state’s militia to serve. Already ill, Governor Griswold died in office in October 1812. As “Mr. Madison’s war” continued, Britain tightened its blockade of New York harbor and Long Island Sound. Any ship that ventured from port could be fired on, its cargo seized, and its seamen forced to serve in the Royal Navy.

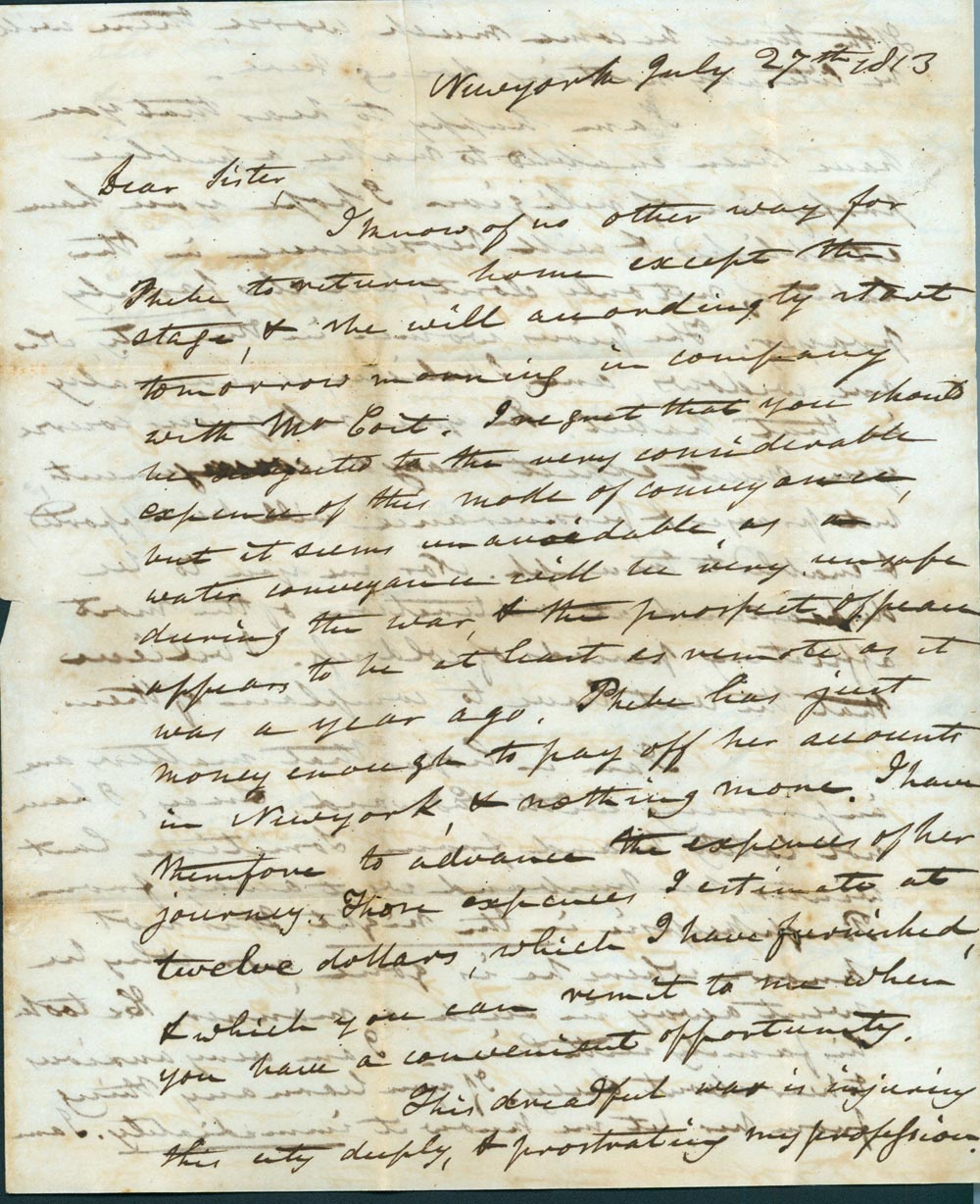

George Griffin, Jr., to Phebe Lord, July 27, 1813. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Phebe Lord waited anxiously for her daughter to return home before the onset of winter, but passage on the Sound had become impossible, as George wrote on November 27, 1813:

Dear Sister:

I know of no other way for Phebe to return home except the stage, & she will accordingly start tomorrow morning in company with Mr. Coit. I regret that you should object to the very considerable expense of this mode of conveyance, but it seems unavoidable as water conveyance will be very unsafe during the war, & the prospect of peace appears to be at least as remote as it was a year ago. Phebe has just money enough to pay off her accounts in Newyork, nothing more. I have therefore to advance the expenses of her journey. Those expenses I estimate at twelve dollars, which I have furnished, & which you can remit to me when you have a convenient opportunity.

This dreadful war is injuring this city deeply, & prostrating my profession. If the times become much worse, there will be literally nothing doing here.

. . . . I hope you will find Phebe improved. She or you must write to us as soon as she gets home, to let us know whether she reaches you in safety. . . .

In haste, Your affectionate brother

Geo Griffin

Defenses in Lyme

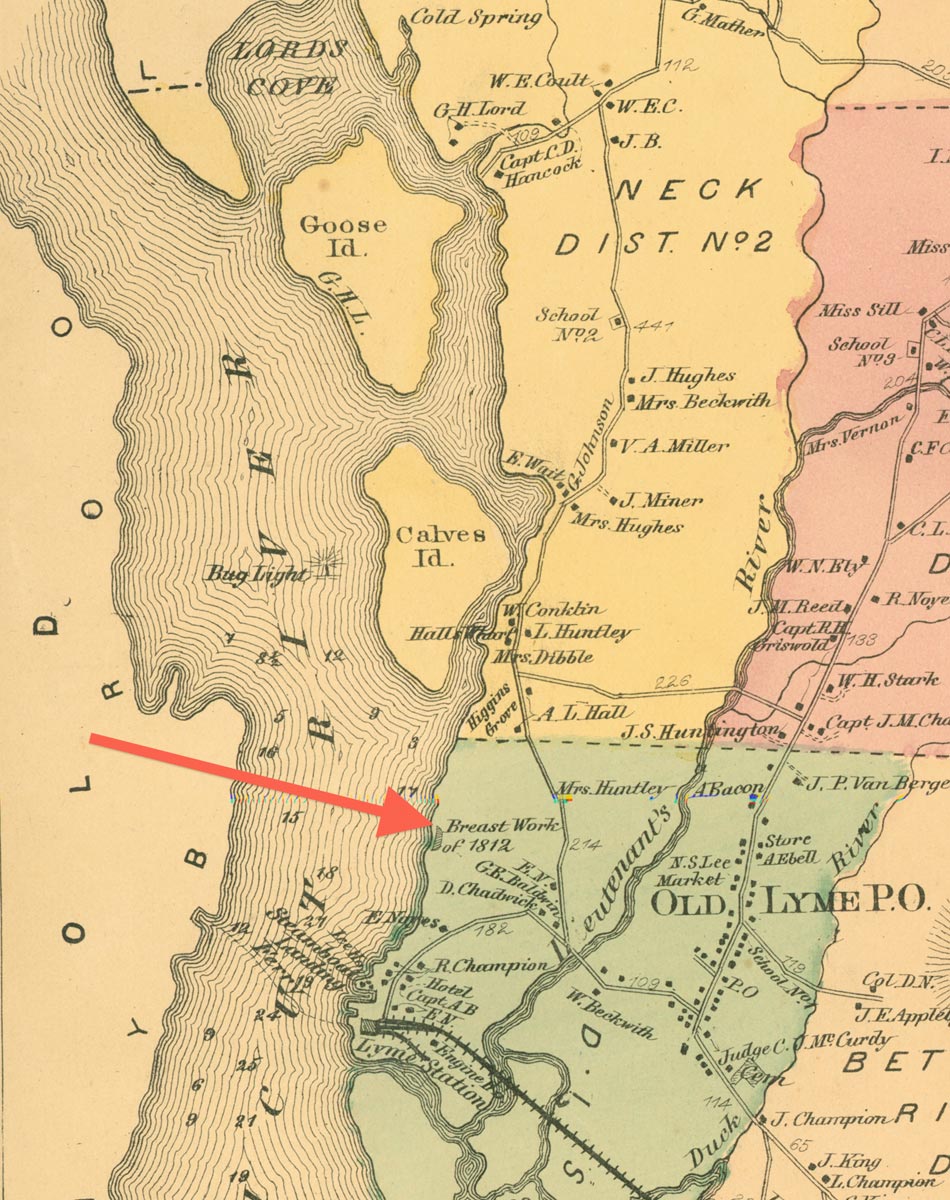

With British warships patrolling the mouth of the Connecticut River, wary Lyme residents posted look-outs on the outcropping thereafter known as Watch Rock. They also constructed an earthen fortification, called a “breastworks” because it was breast-high, above the river. But according to Charles Harvey (1829-1912), who as a boy clerked in John Hart’s general store in the village and discovered cannon balls buried in its debris-strewn basement, the munitions assembled to defend the town against attack were never used.

Watch Rock. LHSA

Local citizens, Harvey said, had “called their men together and placed a field gun with ammunition on the top of Noyes Hill overlooking the river. They discerned, however, that the British forces were much stronger than their own and concluded that to begin action would surely draw upon Lyme an attack by the British and, therefore, concluded they would begin action only after being attacked. Accordingly the British boats passed quietly down the river without so much as a gun having been fired by the Lyme men.”[3]

Across the river in Essex, merchant ships and privateers sitting idle in the harbor proved an easy target. In the early morning on April 8, 1814, three barges and two launches carrying 136 British seamen rowed up the Connecticut River unopposed. The town was spared, but some 26 ships at anchor or under construction were torched. Several more vessels were destroyed at the Brockway’s Ferry shipyard on the Lyme side of the river before the British finished their “incendiary sport.”[4]

Town of Old Lyme (detail showing Breast Work of 1812). F. W. Beers, 1868. LHSA

“This dreadful war”

That afternoon Charles Griswold (1791-1839), a young lawyer in Lyme, joined a crowd at Higgins Wharf to observe the conflagration in Essex. Later he watched from his beach in Black Hall as four British ships withdrew in the darkness from the river unharmed. On April 18, he described the disastrous events to his cousin Ebenezer Lane in Norwich:

Dear Sir –

. . .Although there was a large collection of people on both sides of the river, yet there was no efficient force at all – a mere multitude without order, discipline, or a head – of courage & zeal there was sufficient, but no means of employing them to advantage & effect – I was at Higgins’ wharf in the afternoon of that day, and am convinced that censure cannot fall justly on anyone – I was on our beach when the boats went out of the river, & saw their blue lights. . . .

Estimating the losses, Griswold wrote that “22 sail were burnt” worth $100,000 to $150,000, which was a vast sum at the time, but concluded that nothing could have prevented the Essex raid and no one could be held legally accountable for the damage.[5]

Lyme did not again face military threat, but the ongoing blockade brought financial losses for merchants, shipbuilders, fishermen, and farmers. As commerce slowed, many townspeople suffered from the interruption of transport and trade.

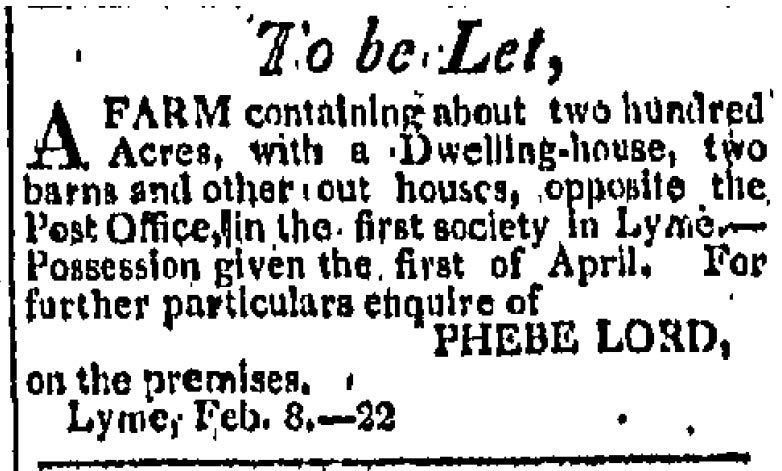

Connecticut Gazette, February 23, 1814.

Two years after her husband’s death Phebe Lord needed income to support her daughters and decided to rent the Lord farm. She also prepared homespun fabric, both flannel and “dressed” cloth, for her brother to place with a New York merchant. On August 25, 1814, George inquired whether she would lower her prices:

Dear Sister

. . . .Your cloth has none of it sold, at least it had not when I last saw the merchant with whom it is deposited. The flannel is good of the kind, but the cloth appears to have been injured in dressing. It is cut in a number of places. The flannel also remains unsold. The merchant thinks that the prices which you fixed are higher than the articles will fetch. Inform me whether you will consent to have them sold for less. . . . This dreadful war has almost ruined every thing. It has destroyed my business & greatly depreciated the value of my property. Bank stock is not worth more than three fourths of what it was. I think that you had better keep your farm for the present. Mrs G. & the children join in love to you & yours. Write soon.

Yours affectionately

G Griffin

After the War

Shipping resumed on Long Island Sound when the Treaty of Ghent ended the war with Britain on December 24, 1814. Young Phebe could again use “water conveyance” to reach New York from Lyme and several times made the journey on the packet sloop Trio. For more than a decade she would teach for months at a time in the school her sisters conducted in the Lord home, then return to the city to pursue her study of miniature portrait painting.

The talented Phebe had many suitors. In 1827 she married a handsome young merchant from Westerly, Rhode Island, named Daniel Rogers Noyes and at age 30 settled permanently in Lyme to run her own school and raise five children. Today the Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library, built in 1898 on the site of her birthplace, honors her contribution to education.[6]

George Henry Yewell, Phoebe Griffin Noyes (detail), ca.1898. Courtesy Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library

[1] Charles P. Noyes and Emily H. (Gilman) Noyes, Noyes-Gilman Ancestry (St. Paul, 1907), pp. 121-124, 165-6; Alma Merry Tatum, For the Love of Books: The Story of the Public Libraries of Old Lyme (Essex, 1997), pp. 28-32.

[2] The album of Daniel Rogers Noyes, Jr., contains the 1812 and 1814 Griffin-Lord letters (Lyme Historical Society Archives). The 1813 letter is courtesy of the Ludington Family Collection.

[3] Sarah Sill Wells Burt, Old Silltown, Something of Its History and People (privately printed, 1912), p. 116. Charles T. Harvey was a nephew of Judge Henry M. and Maria Waite; in 1868 he designed the world’s first elevated railway in New York City.

[4] Richard Radune, Sound Rising: Long Island Sound at the Forefront of America’s Struggle for Independence (Branford, 2011), p. 242; Russell Anderson and Albert Dock, “The British Raid on Essex” (Essex Historical Society, 1981), Courtesy East Lyme Historical Society; Gary Libow, “Masonic Ties Preserved Essex, Town Historian Says,” Hartford Courant, February 4, 1997; Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 (New York, 1869), p. 888; Elizabeth Putnam, Brockway’s Ferry, Lyme, Connecticut: A History and Memoir (Lyme Public Hall Association, 2002), p. 4; Jerry Roberts, “The British Raid on Essex: Setting the Record Straight,” Shoreline Times, May 4, 2012.

[5] Charles Griswold to Ebenezer Lane, April 18, 1814, William Griswold Lane Memorial Collection, Yale University Library, Courtesy Connecticut River Museum.

[6] Phoebe Griffin (Lord) Noyes’ name had alternate spellings during her lifetime; her children decided to engrave “Phoebe” on her gravestone.