On Juneteenth 2021, a newly-declared federal holiday, we commemorate the end of African American enslavement in Lyme two hundred years ago. Fourteen Witness Stones installed along Lyme Street in Old Lyme mark the locations where some of the over 200 people enslaved in town lived or worked. For more information, visit WitnessStonesOldLyme.org.

By Carolyn Wakeman

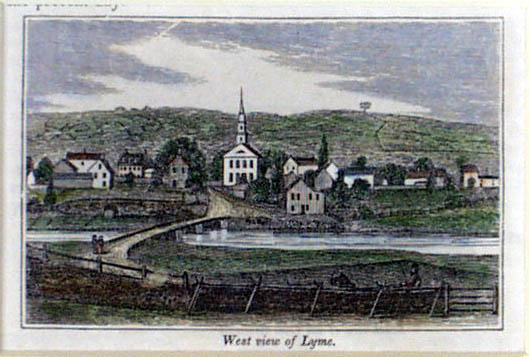

Featured Image: John Warner Barber, West View of Lyme, Connecticut, ca. 1836. Colored woodcut on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mr. Richard Ferris, 1957.2

The last person known to be enslaved in Lyme was “set at liberty” in 1820. Land records document in legally precise language the emancipation of “Samuel, a Slave,” on November 8: “This may certify that the subscribers, two of the civil authority in the Town of Lyme, county of New London & State of Connecticut, in pursuance of the Statute in such cases made & provided, have inquired into the health and age of Samuel, a Slave belonging to the Estate of Joseph Noyes, late of Lyme deceased” [punctuation added]. The subscribers found that “the sd Samuel is in good health and is not of a greater age than forty five years or less than twenty five years.” They also found “that the said Samuel is desirous of being made free.”[1]

William Noyes, Esq., Joseph’s younger brother and one of the subscribers, had made a similar application three years earlier on January 7, 1817, when he emancipated his “female slave” Crusa, a Negro. Then also Lyme’s civil authorities certified that they had “made due inquiry & examination of the circumstances of sd Crusa” and determined “that she is in good health and that she is not of greater age than forty five or less than twenty five years old.” Crusa had been born into hereditary slavery in the Noyes household on September 14, 1778, and the civil authorities certified that they “are convinced that she is desirous of her liberty at this time.”[2] William Noyes, Esq., stated that he did “hereby give full liberty & free whatsoever she pleases and to act in all respects as any free person can.”

The language used in certifying the emancipation of Samuel and Crusa reflects specifications in a law enacted by Connecticut’s General Assembly in 1792. Provided that a slave, based on an actual examination, was not younger than twenty-five or older than forty-five, was in good health, and was “desirous” of being set free, local authorities could certify the slaveholder’s exemption from financial responsibility for the formerly enslaved person.[3] Whether Samuel or Crusa had desired at an earlier time to act “as any free person can” is not known, but her older brother Pompey, born August 30, 1776, was not offered that choice. Two weeks before Crusa’s emancipation, Pompey ran away. The Connecticut Gazette posted a runaway notice on Christmas Day, December 25, 1816: “Negro man Pomp, ae 40 has run away from Joseph Noyes of Lyme. Pomp is blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other.”[4] No manumission record for Pomp, who died at age 46 on August 9, 1822, has been found. Whether he returned to the Noyes household is not known.

Joseph Noyes house, built ca. 1814 on the site of Rev. Moses Noyes’s homestead. Lyme Historical Society Archives (LHSA) at the Florence Griswold Museum

By then African Americans had lived in bondage in Lyme for a century and a half. A New London County Court record in 1670 notes the summons of “ye Negro servant Moses” to appear at its June session with his owner Richard Ely. A land record three years later in 1673 lists “two nigers” among Ely’s property on his Six Mile Island Farm.[5] As support for abolition grew after the Revolution and incentives for manumission increased, the number of persons enslaved in Lyme, and elsewhere in Connecticut, declined significantly, but not in Noyes family households.

Judge William Noyes, a grandson of Lyme’s first minister, had inherited in 1743 at age fifteen the half-time use, once he came of age, of his father’s enslaved servant Jube. In 1774, the year that Connecticut passed a law prohibiting the further importing of slaves into the state, a census count showed 124 Negroes in Lyme, almost all of whom were enslaved. A family notebook shows that Judge Noyes held four persons in bondage that year, Prince and Jenny, their daughter Nancy, age 3, and their infant son Prince, Jr. In 1788 when Judge Noyes assembled with other delegates in Hartford to ratify the Constitution of the new Republic, whose Preamble declared all men to be created equal, Prince and Jenny’s family had grown to include four younger children, Pompey, Crusa, Temperence, and Jordan, age one. The federal census in 1790 shows five enslaved persons in Judge Noyes’s household, two in the household of his son Joseph, and one held by his son William, Jr. Two decades later in 1810, six of the nine persons still living in bondage in Lyme resided with the Noyes family. Joseph’s household included six Free White Persons, along with two classified as Other Free Persons and two designated as Slaves. One of the slaves was likely Samuel and the other almost certainly was Pomp.

Judge William Noyes house, later the Bee & Thistle Inn. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

The census enumeration taken a decade later, on August 7, 1820, three months before Samuel was officially set free, lists no enslaved persons in Lyme, perhaps because his emancipation was pending. That year 25 persons lived on the three Noyes estates that stretched along both sides of the New London-Lyme Turnpike. Seven worked in agriculture, and ten were Free Colored Persons. Only William Noyes, Jr.’s, household includes a Free Colored Person between ages 22 and 44, so Samuel may have moved back and forth between the houses in which he, Crusa, and Pompey had long resided. Samuel may have worked in 1820 on the estate where William, Jr., had recently built a stately new home that would later become the Florence Griswold Museum.

Samuel Freeman’s early life has not been traced, but an anonymous ledger notes in 1805, when Joseph Noyes lived briefly with his family in East Haddam’s Millington parish, that “Capt. Joseph Noyes of East Haddam had Negro boy SAM.”[6] Samuel later married Sabina, called “Biner”, a granddaughter of Prince and Jenny, born into slavery in Judge Noyes’s household. Samuel and Sabina’s children Sophie and Henry, born in 1816 and 1821, spent their early years on the Noyes estates.

Florence Griswold House, formerly William Noyes, 3rd, house, built in 1817. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

The institution of slavery remained deeply entrenched in Lyme as Samuel and Sabina grew into adulthood. He was about 35 in 1820 when the heirs of Joseph Noyes set him free, and Sabina was then 27. Her hereditary enslavement would have ended when she turned 25, according to the provisions of the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784. Enslaved persons born before March 1, 1784, remained slaves for life unless they were manumitted by their owners. Lyme’s vital records include the certification by William Noyes, Esq., that “Biner Negro, Daughter of Nancy Servant of Willm Noyes was born on the 15th day of March AD 1793.” When Connecticut’s General Assembly passed an “Act to Prevent Slavery,” prohibiting enslavement in the state, on June 12, 1848, Sabina was 55.

Only a few details have emerged about Samuel’s life after his emancipation. In November 1827 he was “the victim of an assault,” according to New London County court records.[7] In 1830 he was head of a separate household in Lyme that included eight Free Colored Persons. In 1840 two of the four Free Colored Persons in his household “worked in agriculture.” At the time of the 1850 census, which lists Samuel’s age as 65 and Sabina’s as 55, they lived with their children Sophia, age 30, Henry, age 29, and three young grandchildren, including William H., age one. Samuel’s birth and death dates have not been found, but his widow Sabina died in Old Lyme on June 24, 1862, a year after Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter to start the Civil War.

Little is known about Samuel and Sabina’s children, raised in the shadow of slavery. In 1845 Lyme’s Justice of the Peace Stephen J. Lord issued an arrest warrant for Henry Freeman, then 24, following an accusation that he had fathered the bastard child of a single woman. Judge Lord ordered him to appear at the almshouse and make “due return” about his “doings,” but the outcome of the case is not known.[8] Three years later on December 1, 1848, according to the town’s vital records, “Wm Henry Freeman, Black, [was] born in Lyme 1st School Society to Sophie Freeman, Illegitimate.” Sophie married Joseph Jeston of Westbrook on January 1, 1854.[9]

The enduring practice of slavery in Lyme also shaped the experience and expectations of the town’s civil authorities, including those who emancipated Samuel and Crusa and summoned Henry Freeman to the almshouse. Justice of the Peace Richard McCurdy had freed Corrydon in 1813, and Selectman Thomas Sill had freed “Caesar a negro Slave” a decade earlier in 1803. The other three Justices of the Peace who acted “in pursuance of the Statute in such cases,” Henry M. Waite, Charles Griswold, and Stephen J. Lord, had not themselves held servants in bondage but had grown up alongside the enslaved persons residing in the households of their parents and grandparents.

Lyme Street, showing, on left, house formerly of Richard McCurdy; at center, house formerly of Stephen J. Lord. LHSA at the Florence Griswold Museum

[1] Lyme Land Records 28:649.

[2] Noyes scrapbook, Lyme Historical Society Archives (LHSA) at the Florence Griswold Museum; Lyme Land Records 28:113.

[3] See David Menschel, “Abolition Without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery, 1784-1848,” Yale Law Journal 111 (2001), p. 205.

[4] Noyes scrapbook; Barbara W. Brown and James M. Rose, Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650-1900 (New London, 2001), p. 272.

[5] Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse (Middletown, 2019), pp. 6-7.

[6] Brown and Rose, p. 570.

[7] Ibid., p. 148.

[8] Oliver Lay Papers, LHSA.

[9] Brown and Rose, p. 149.