By Patty Devoe

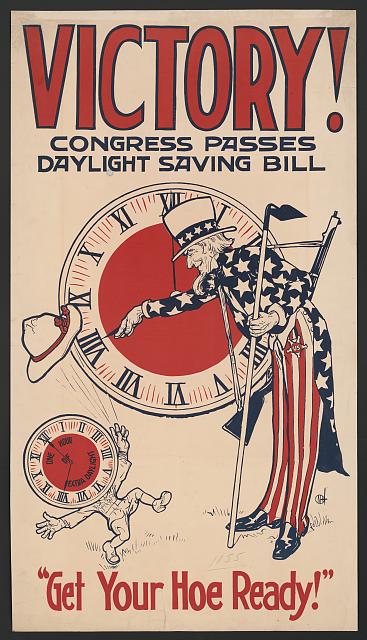

Featured Image: Victory! Congress passes daylight saving bill, 1918, – Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Two curious comments in letters penned in 1921 by Walter Magee, close friend of Lyme Art Colony painter Platt Hubbard, open up a bit of history that is still relevant today. For over 100 years, the practice of turning clocks ahead one hour for daylight saving time has been debated, manipulated, and legislated. The references Magee makes to this temporal shift provide amusement and perhaps offer a dose of patience useful in today’s turbulent world.

A letter written by Walter Magee on May 11, 1921, states: “I wakened early so am going to New London for something as they have daylight saving and we do not, it makes it late over there unless one starts early.” New London is approximately 15 miles east of Old Lyme. A letter four days later describes another bump up against the daylight saving time conundrum. Magee writes: “must go and dress as I leave directly after lunch, that hour difference makes it necessary. If I leave at two here it is three there.” This time he is headed 34 miles west towards New Haven. His comments appear to mean that Old Lyme was observing standard time while New London and New Haven were observing daylight saving time.

Platt Hubbard and Walter Magee, ca. 1933. Platt Hubbard Papers, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

Three hundred separate time zones blanketed the United States in the mid-19th century just as the dream of modern and fast transportation by rail was becoming a reality. Obvious logistical problems occurred as discrepancies in time caused accidents, missed connections, and general confusion. Driven by the needs of railroads and, by association, those of manufacturers, citizens experienced the first of many alterations to a systemized time keeping system. Efforts to conserve energy during World War I brought an important shift in time keeping practices, daylight saving time. The Calder Act, or Standard Time Act of 1918, allowed for daylight saving time to be observed between March and October.

So controversial was this mandate that Congress repealed the daylight saving time provision in 1919 and returned the entire country to standard time only. However, Congress left it to the discretion of states to decide whether or not to observe daylight saving time, except where it pertained to transportation and to federal agencies, for example, railroads and post office operations. Connecticut decided not to mandate either daylight saving time or standard time but instead to allow individual towns to decide what time it was within their borders.

Woman wearing two watches while traveling to keep track of daylight saving time and standard time. “Train Users Confused by New Daylight Saving Time,” Boston Post, April 26, 1920, p.2

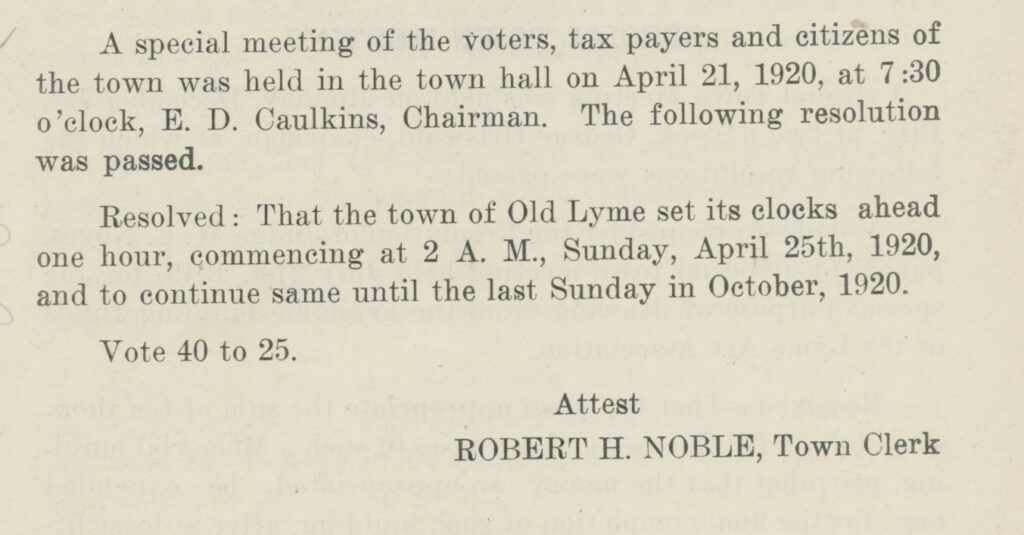

The residents of Old Lyme were invited to a special town meeting on April 21, 1920, to vote on whether to approve daylight saving time. Town meeting records show that by a vote of 40 in favor and 25 opposed, Old Lyme decided to observe daylight saving time from April 25, 1920, to the last Sunday in October.

Excerpt from the Old Lyme Annual Report, 1920. Old Lyme Town Reports, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

Elsewhere in Connecticut citizens who engaged in work activities dictated by the rising and setting of the sun, like farmers, saw no point to this meddling. The Preston City Grange summed up the farming community’s sentiments in a letter published in the Norwich Bulletin on February 11, 1921: “If public leaders…. wish to see Connecticut cities more adequately sustained by Connecticut farms they will see to it that daylight is used as the Almighty Creator meant it to be used and will see to it that so-called daylight saving, adopted in intrigue and hysteria, shall be abandoned in sobriety and in perpetuity.”

Connecticut capitulated to such pressure in 1921 and ruled that standard time would be the official time throughout the state. However, local ordinances could establish daylight saving time. So went a game of musical chairs as businesses, schools, theaters, and various other organizations decided what time keeping method they would observe. Yale University recognized daylight saving time on its campus while the city of New Haven stayed on standard time.

A report in the Norwich Bulletin on April 14, 1921, confirms the extra effort Walter Magee had to put into planning his daily activities: “Mayor E. Frank Morgan of New London stated he will take no action relative to daylight saving observance in New London. . . .While he is personally in favor of daylight saving time, he feels that to do anything to further it as mayor would be contrast to the state law and he is declining even to issue a proclamation requesting such observance by the citizens in general… all clocks in the city hall and all public buildings owned by the city of New London will remain on standard time.” Despite the mayor’s official stance, a ferry scheduled to run from New London to New York adopted daylight saving time, according to an advertisement released on September 27, 1921.

Advertisement for New London Ferry, Norwich Bulletin, September 27, 1921

Daylight saving time still provokes controversy today. Federal and state governments continue to share decision making about time zones, and it is not possible for states to implement year-round daylight saving time unless Congress acts to allow it. As of June 2020, thirty-two states have considered adopting year-round daylight saving time. Thirteen states have passed legislation to that effect, if and when such action is possible under Federal law, but some professional organizations oppose such a change.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine is one group that supports year-round observance of standard time, noting that “it is the best choice to most closely match our circadian sleep-wake cycle.” An article published in The Wall Street Journal in September 2020 by Dr. Dinah Miller, “To Combat Covid, Don’t Turn the Clock Back,” cites numerous adverse consequences to turning clocks back one hour for daylight saving time. She also notes the absurdity of extending daylight saving time in response to lobbying efforts by the candy industry, which argued in 2005 that longer days would aid Halloween candy sales.

The comments in Walter Magee’s letters in 1921 clearly remain relevant today. We are still debating the merits and demerits of daylight saving time, and in the meantime must continue to have a bit of patience and humor in planning our daily activities.

Sources:

Position Statement, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, “Eliminate Daylight Saving Time”

https://aasm.org/american-academy-of-sleep-medicine-calls-for-elimination-of-daylight-saving-time/

James J. Kenneally, “’An Hour of Light for an Hour of Night’: Daylight Saving in Massachusetts,” The New England Quarterly (September 2005), 78:3, 440-447.

Dr. Dinah Miller, “To Combat Covid, Don’t Turn the Clock Back,” The Wall Street Journal (September 4, 2020).

National Conference of State Legislatures, “Daylight Saving Time, State Legislation” 7-22-2020. NCSL.org

Erin Blakemore, “The Odd History of Changing Our Clocks for Daylight Saving Time,” National Geographic (November 1, 2019) https://apple.news/A94NJzi5yQG-7JNXdWiLHGg

The New London Day (April 4, 1921; April 23, 1921; April 25, 1921).

The Norwich Bulletin (February 11, 1921) https://www.newspapers.com/image 320383023 (Thursday, April 14, 1921) https://www.newspapers.com/image/320390946

(Tuesday, September 27, 1921) https://www.newspapers.com/image 320416606

Old Lyme Town Meeting Record (1920), 2:56.

Chris Pearce, “The Great Daylight Saving Time Controversy” (Australian ebook, 2017) books.google.com

Platt Hubbard Collection (150-80, 150-81). Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum.

The Vermont Tribune (March 25, 1921) https://www.newspapers.com/image/491163783