By Carolyn Wakeman

The fire that ravaged the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris on April 15, 2019, recalls the blaze that shocked Old Lyme residents who watched through the night as flames consumed the town’s historic white church in 1907.

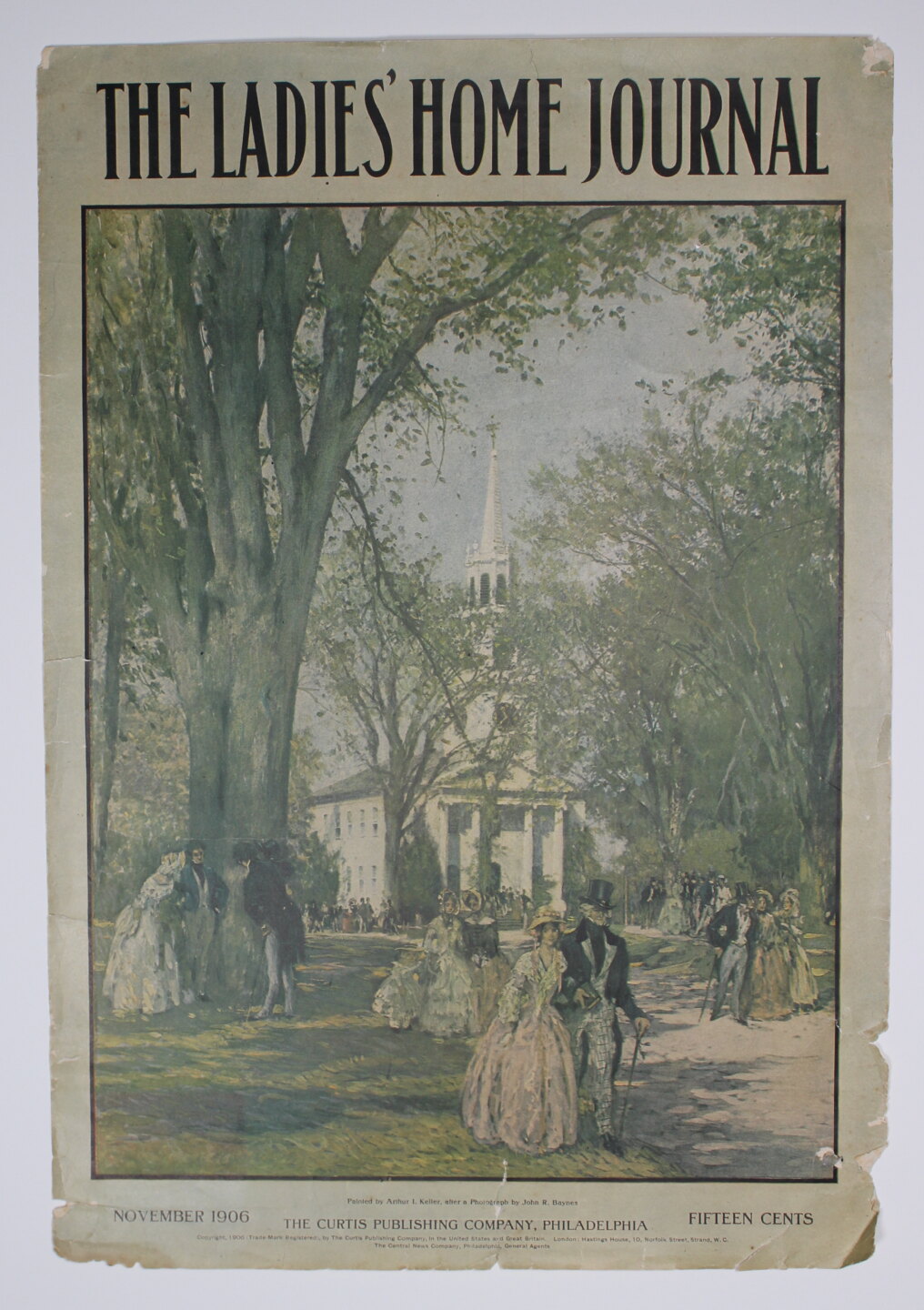

Featured Image: Arthur I. Keller, Ladies Home Journal cover (November 1906), showing a nostalgic view of the church with an imagined congregation in an earlier era. Lyme Historical Society Archives

Cinders rained down in the early hours of Wednesday, July 3, 1907, as fire devoured Old Lyme’s celebrated white church. The steeple bell tolled the midnight hour, then fell silent as flames toppled the spire, blackened the surrounding elms, and layered the town green with ash. Liveryman John Sterling discovered the blaze shortly before midnight when he returned to his stables behind the Old Lyme Inn after an evening trip to the ferry dock. At a furious pace, he rode through the street to alert the sleeping community. “Soon after twelve was roused by cry of fire,” Rev. Edward M. Chapman noted in his journal on July 3. “Looked out & saw light on north Church windows which I hoped was caused by some exterior fire. It was the Church itself however, as a voice from the street soon assured me.”

Old Lyme Inn proprietor Herbert Caulkins arrived at the church within minutes of John Sterling’s warning. Hoisting himself up to a window, he could see fire already leaping through two gaping holes in the roof. “It was but a short space of time before nearly the entire population of the town was at the scene,” reported The Deep River New Era. Townspeople fought through the night to contain the blaze, pumping water from an 8,000-gallon tank at Charles Ludington’s house next door to fill waiting buckets. Long before daybreak, the meetinghouse, the newly renovated Conference House, and the horse sheds behind had been lost to the flames.

Old Lyme Church interior decorated for the harvest season, ca. 1889. LHSA

“The Church could not be saved,” Katharine Ludington wrote the next day to her brother. “It was a mass of flame five minutes after I first saw the fire.” Their own house fifty yards to the south had been saved “only by the most heroic efforts I have ever seen,” she wrote. “The entire town turned out and worked in a way which stirs me to think of, risking their lives in a rain of falling, burning wood, on the roof, in heat which broke all the glass on that side of the house & charred much of the wood. No one thought at first that the house could stand.” Later she recalled in a family memoir how “the old spire with its heavy bell. . .fell with an awful crash. A semi-circle of silent people stood on the green watching the familiar and sacred landmark go. Many were sobbing, and all were still, as if at service.”

Congregational Church and Charles H. Ludington home (to the left of the church), 1905. Ludington Photo Album. LHSA

Arson seemed certain. Just two weeks earlier the Ludingtons’ stables had burned suspiciously after midnight. On the afternoon before the fire, no trace of smoke had been detected inside the meetinghouse when Katharine Ludington sang beside the piano with other church women. Not only did the blaze break out on the pulpit platform where no lamp had been lit since the previous Sunday’s service, but the church burned precisely on the anniversary of the lightning fire that had consumed the previous meetinghouse in 1815. “If such a thing is possible the fire that destroyed the Congregational Church at Old Lyme is going to be ascertained,” The New Era declared. “The leading citizens of the town are determined in this and steps have already been taken toward a solution of the mystery.”

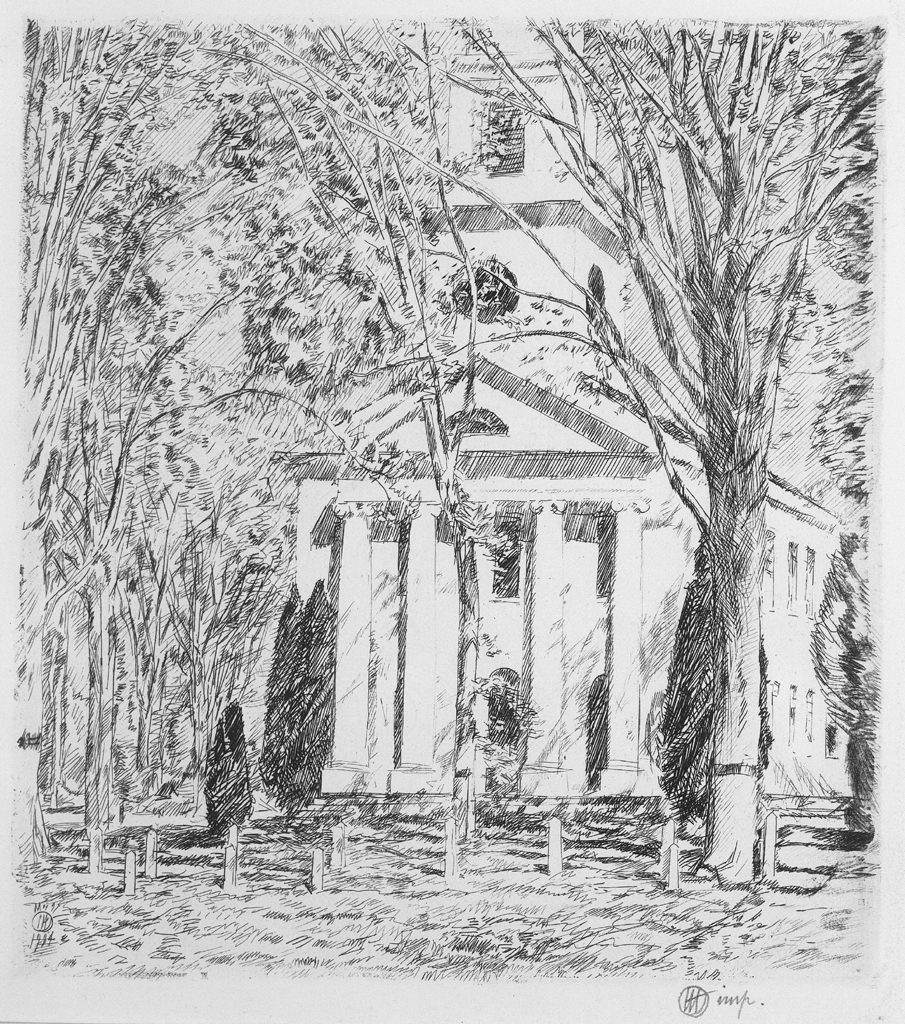

Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Church at Old Lyme, 1924. Etching, Florence Griswold Museum; Given in memory of Daniel Woodhead, Jr., and Henry B. Day

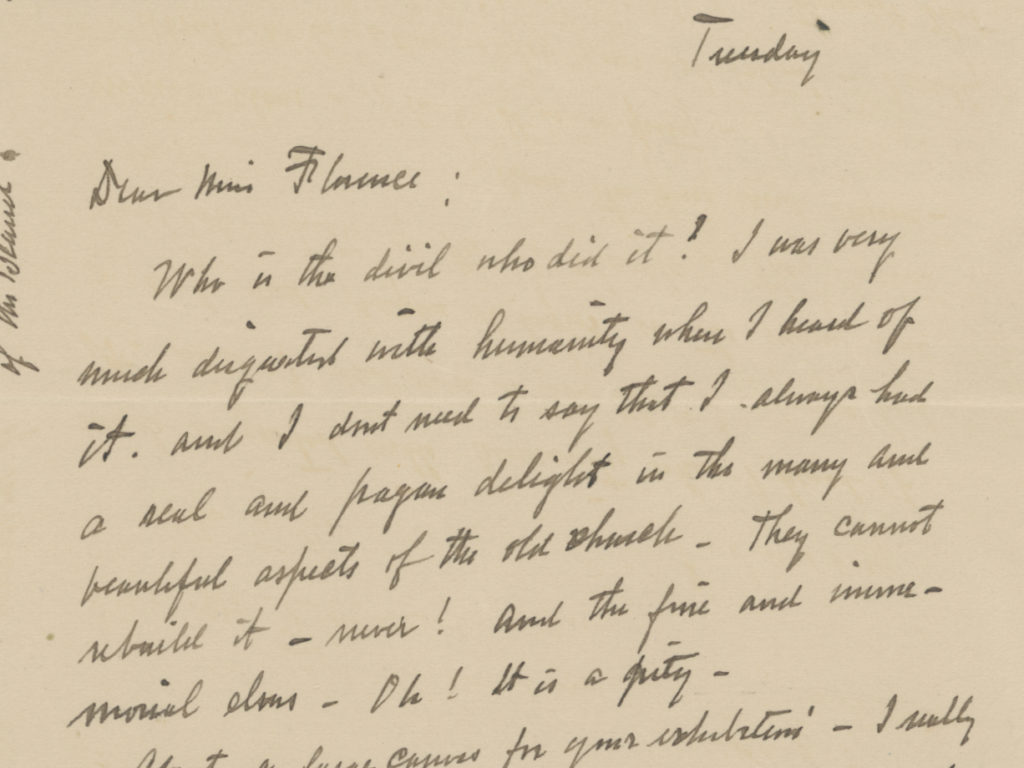

Childe Hassam (1859-1935), the most prominent of the landscape artists who summered in Old Lyme, had painted three views of the historic church and expressed outrage to Florence Griswold after the fire. “Who is the devil who did it?” he asked. “I don’t need to say that I always had a real and pagan delight in the many and beautiful aspects of the old church. They cannot rebuild it—never! And the fine and immemorial elms—Oh! It is a pity.” For almost a century the church beside the green had seemed to define the character of the village, and people struggled for explanation. “Perhaps we loved it too much and thought more of the shell of our religion than we did of the kernel,” Katharine Ludington wrote to a cousin ten days later.

Childe Hassam to Florence Griswold, 1907 LHSA.

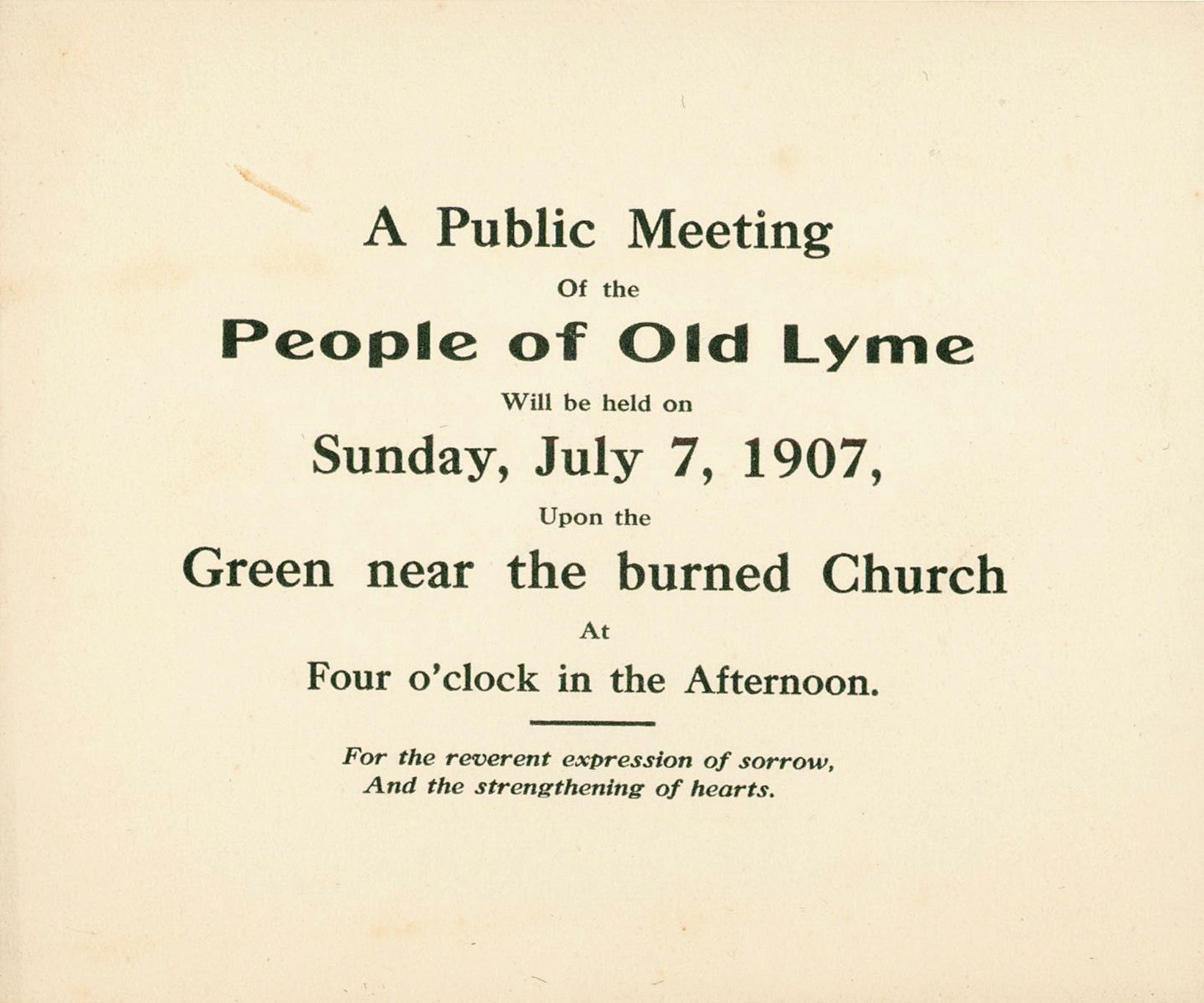

Judge Walter C. Noyes, a descendant of the first minister whom President Theodore Roosevelt had appointed to the U. S. Circuit Court for New York, addressed the significance of the meetinghouse at a solemn public gathering beside the ruins: “It was not as a fine building that the old church was most dear to us. It entered into our inner-most lives.” Following his remarks, Frank Vincent Du Mond, a leading member of the Lyme art colony, “voiced the sorrow of the artists for the loss of so much beauty.” The whole town mourns, Katharine Ludington wrote, “& is drawn together in a wonderful way—no Fourth of July celebrations were allowed, & the whole talk is of re-building the Church–& of probing the cause of the fire, for no one doubts that it was of incendiary origin.”

Notice of Public Meeting, July 7, 1907. LHSA

To calm fears about “fire bugs” who might strike again, detectives from Hartford searched the ruins for evidence, and a security guard kept the charred Ludington home under surveillance. Worry mingled with grief as concern spread about the identity of the fire bugs. “The matter will not be allowed to drop,” The New Era reported on July 19, but by summer’s end the arson investigation had stalled. Hopes of an indictment revived in November when two arrests followed an unsuccessful attempt to burn the town’s consolidated school. An unemployed town resident claimed in court that his co-defendant had “told him on the night of the burning of the schoolhouse that he had burned the Lyme church.” The allegation brought a flurry of headlines but could not be substantiated.

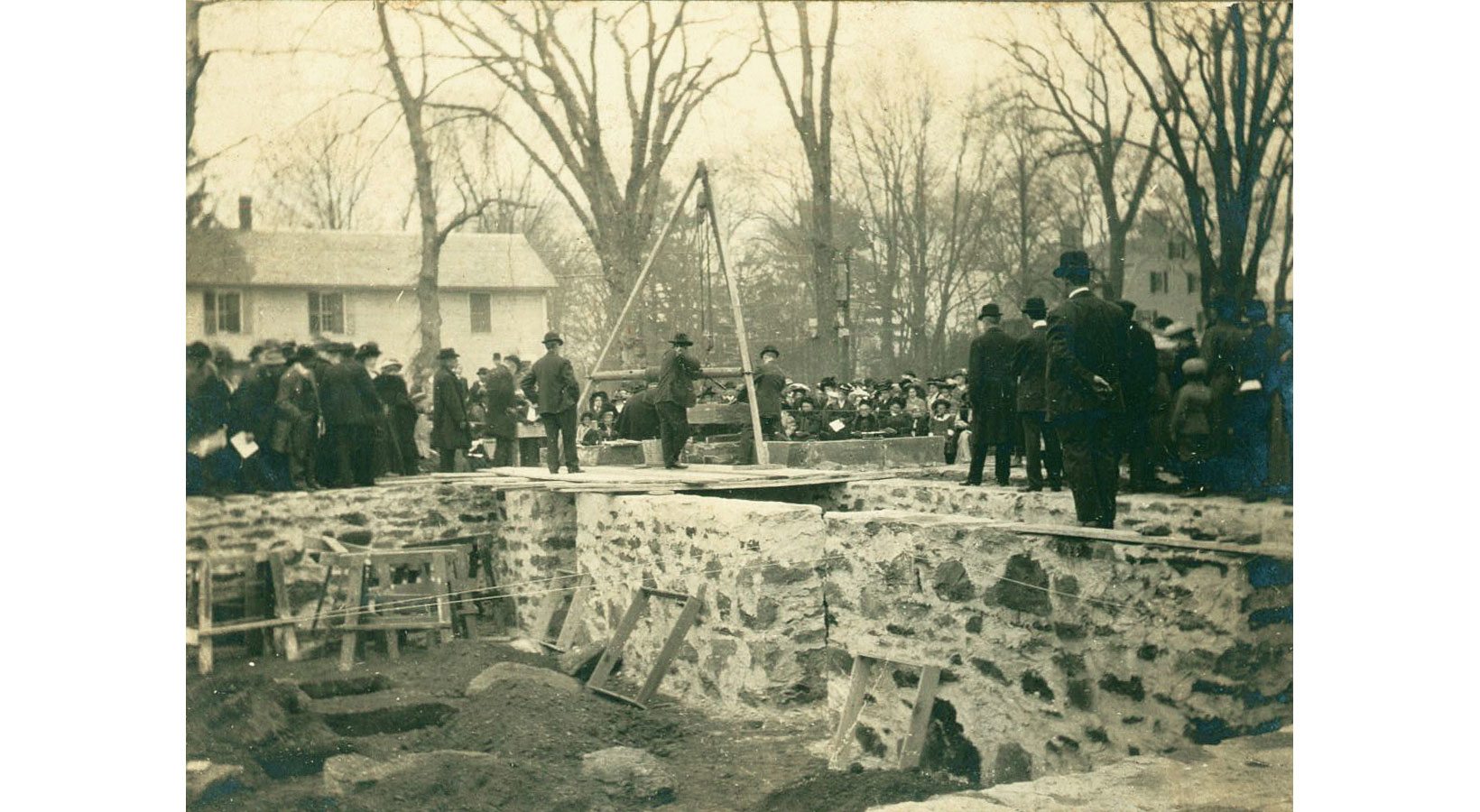

Laying the cornerstone for a new meetinghouse, 1908. LHSA

Suspicions persisted that one or both of the defendants in the school fire had started the meetinghouse blaze, but the mystery was never solved. An anonymous observer who reflected sadly on the ruined church and its imperishable memories remarked: “High Heaven somewhere looks down upon a guilty man with a scar upon his heart as red as the flame that his hand kindled.”

Restoring Old Lyme’s meetinghouse, 1909. Ludington Family Collection, LHSA

A version of this article will appear in Carolyn Wakeman, Forgotten Voices: The Hidden History of a New England Meetinghouse, forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press.