by Carolyn Wakeman

Feature Photo (above): Martha Noyes, ca. 1860. Courtesy Werneth Noyes

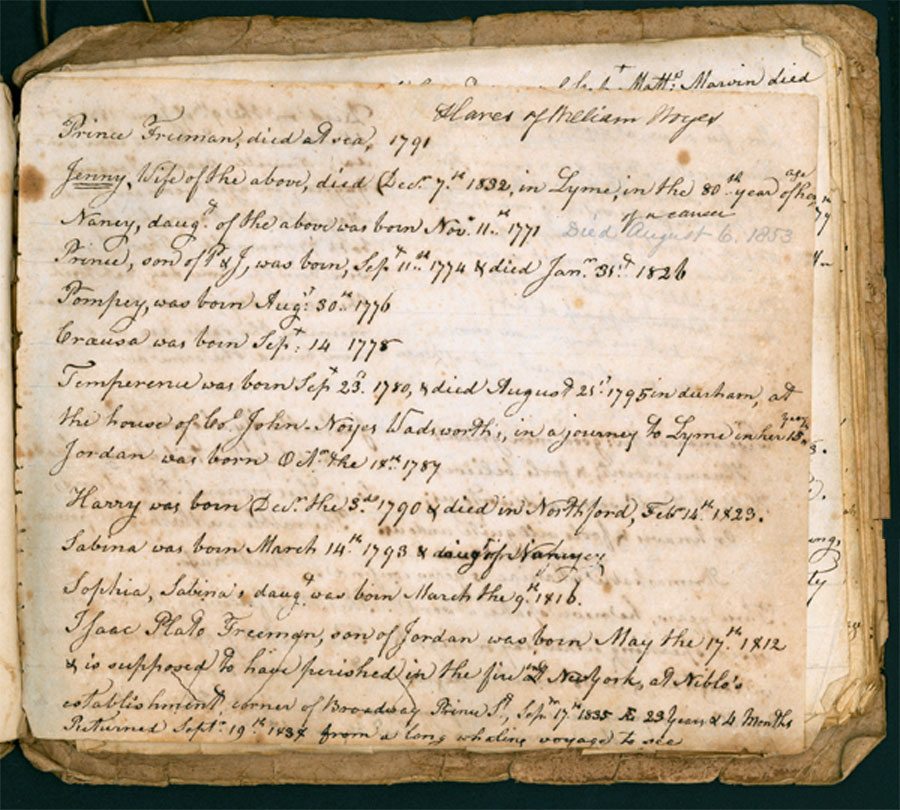

Amid the recipes, medicinal cures, and obituary clippings pasted into a simple string-bound scrapbook appears a hand-written list of Judge William Noyes’ (1728–1807) slaves. Kept initially by his great-granddaughter Mary Ann Noyes Learned (1818–1875) and later maintained by her cousin Martha Noyes (1833–1874), the scrapbook documents the family’s Negro servants over four generations. Martha’s older sister Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824–1900) had known the last of them, a “good Christian woman” called “old black Jenny” (1748–1832).[1]

Martha Noyes, Scrapbook, ca. 1855. LHSA

Martha Noyes, Scrapbook, ca. 1855. LHSA

Coming of Age

Jenny came of age during the decades preceding the revolutionary war when slavery reached its peak in Lyme. The census taken in 1756 when she was a child of eight counted 2,762 whites and 100 Negroes in town.[2] One in sixteen residents was black, and most if not all lived in servitude. “In the palmy days before the Revolution,” historian Martha J. Lamb (1829–1893) wrote in Harper’s Magazine more than a century later, “all the consequential families in Lyme owned negro slaves.”[3]

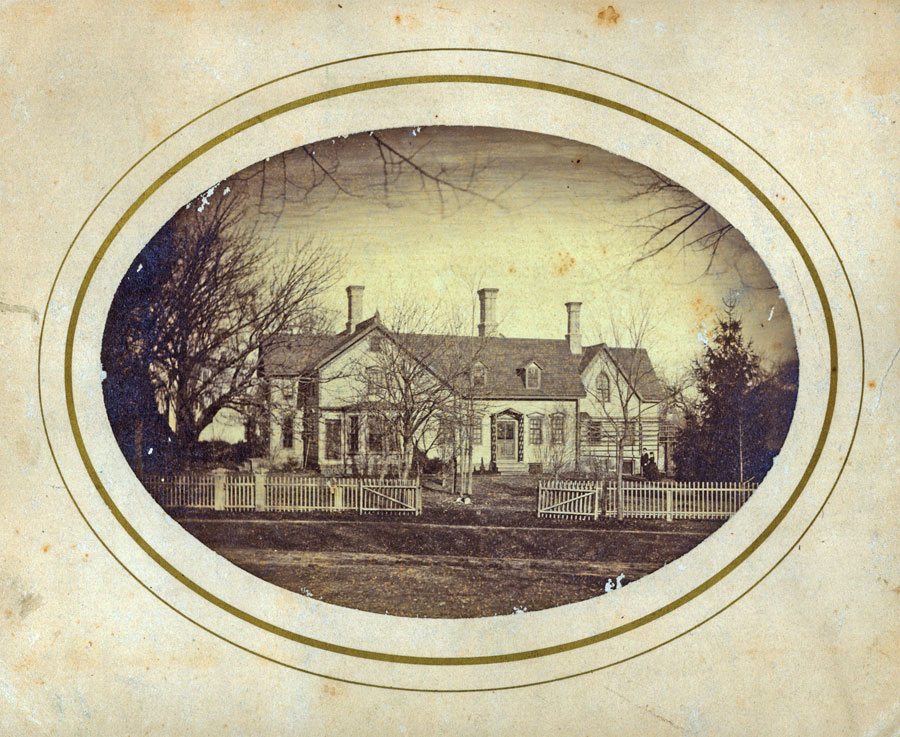

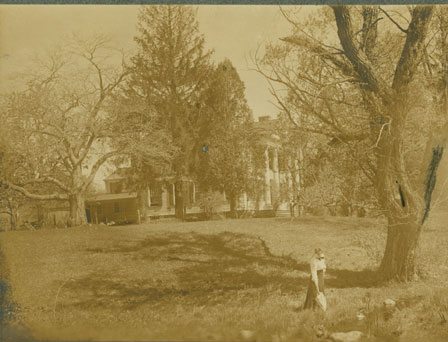

John McCurdy house, ca. 1890. LHSA

John McCurdy house, ca. 1890. LHSA

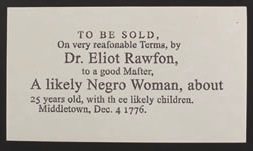

During Jenny’s youth slaves were commonly distributed within families or purchased from nearby owners who had accustomed them to local servitude. More recent arrivals were also available from merchants or ship captains who returned from the West Indies with Negroes to sell in New London or Middletown. Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917) was likely referring to the servants of her grandfather John McCurdy (1724–1785), one of Connecticut’s wealthiest merchants, when she wrote in a five-volume history of local families: “It is said that, in early times, cargoes of Negro slaves were brought up the Connecticut River, and sold out from place to place.”[4]

Jenny was twelve when Gurdon Salsonstall, Jr. (1708–1785), son of a prominent New London minister and Connecticut governor, advertised in the New London Summary in 1760 his intention to sell “2 Negro men, just imported.”[5] She was eighteen when a ship captain in Middletown named Timothy Miller (1743–1816) placed a notice in the Connecticut Currant in 1766 offering three Negro youths for sale at his home. His terms were flexible: “To be sold for Cash or 6 Months Credit, with Security, One Negro Boy, about 17 Years old; Two Girls ditto, about 10 or 11 Years old, have been in the Country about 3 Months, by Timothy Miller, at his House in Middletown. N. B. Beef, Pork, or Grain, will be taken as Cash.”[6]

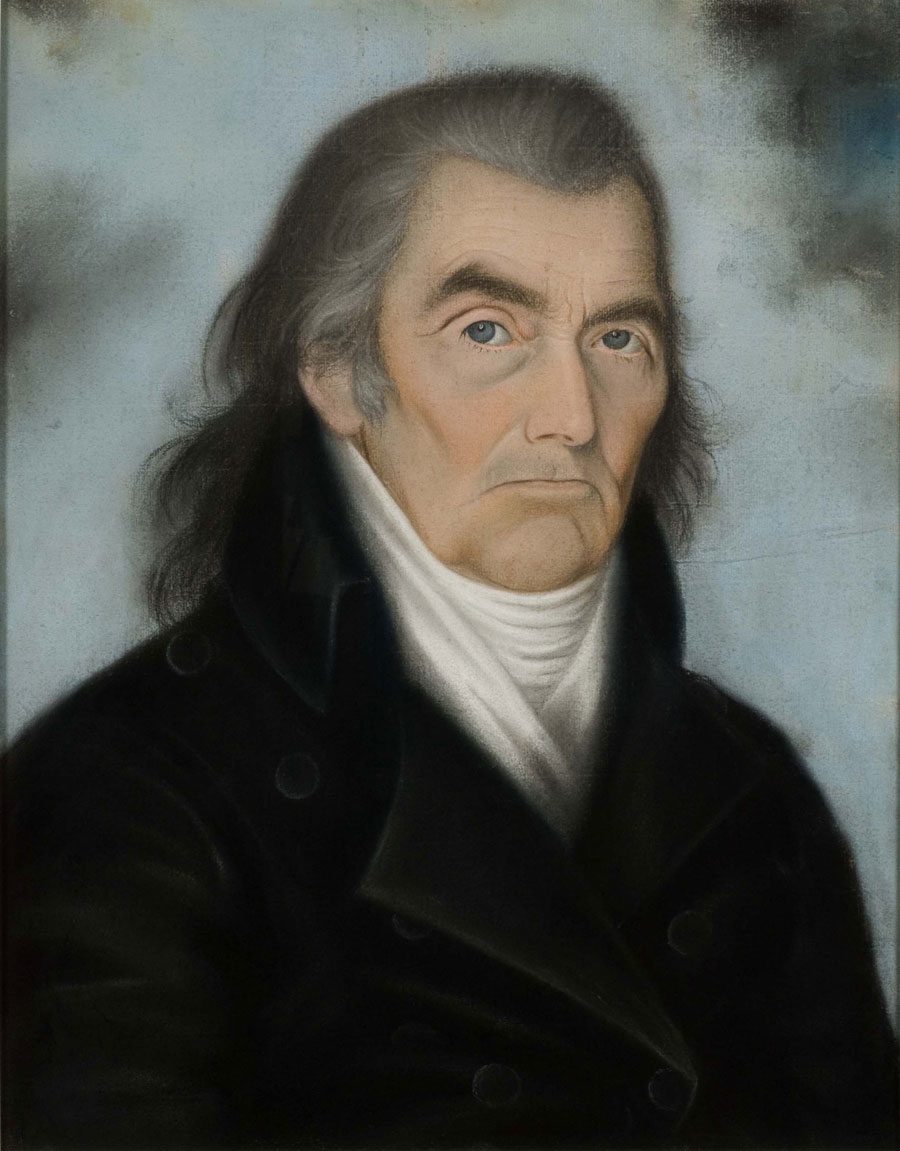

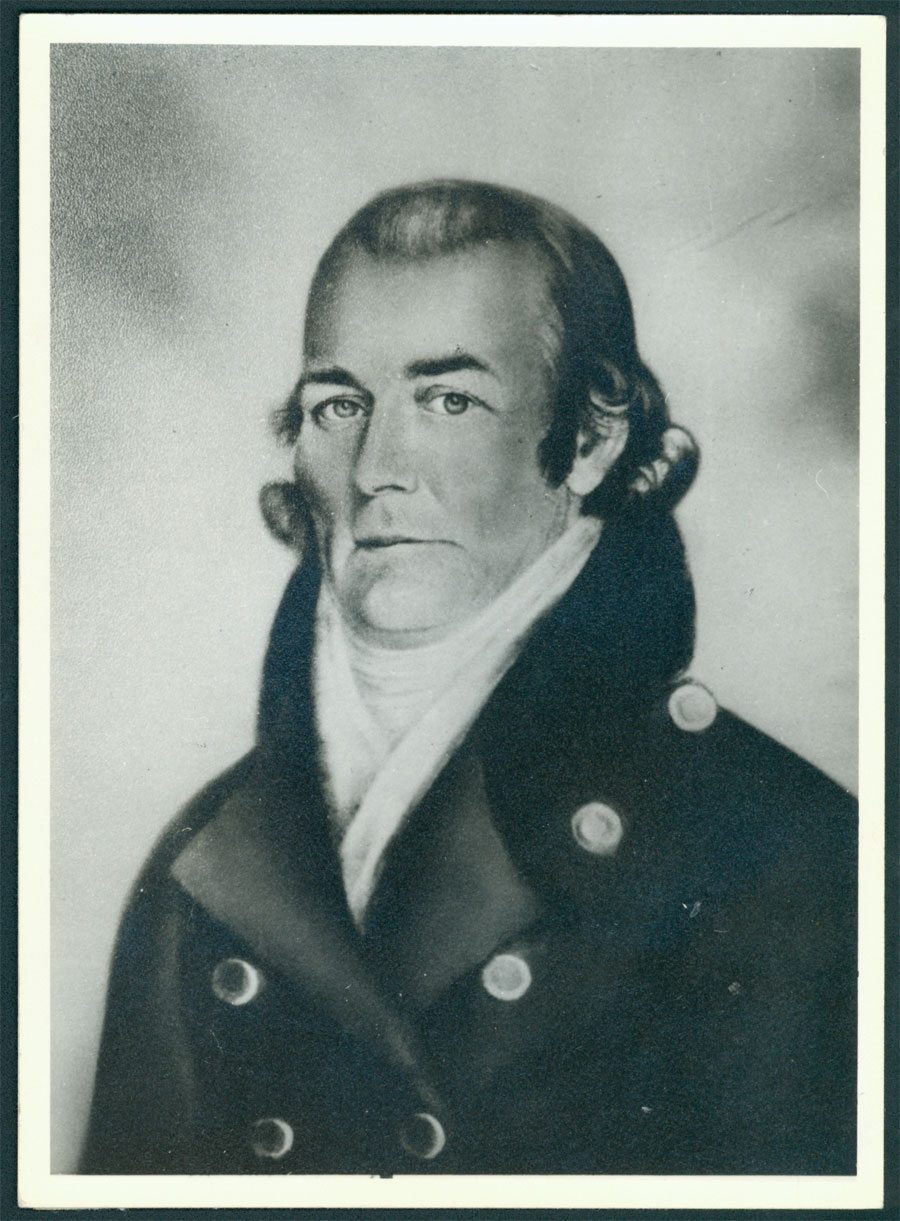

James Martin, Judge William Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John and Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

James Martin, Judge William Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John and Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

The start of Jenny’s service to William Noyes cannot be dated, but she was not his first slave. He was fifteen when his father Moses Noyes 2nd (1678–1743) died and left “all my land called the Homestead” and “my Negro man Jube” to his elder son Moses Noyes 3rd (1714–1786). The will specified that his younger son William when he came of age would receive half of Jube’s time for six years. It also bequeathed two slaves to his widow: an unnamed “Negro woman” and a youth, “Rich Jimmie (by name) until he comes of age.” The estate inventory valued “one Negro Man Servant named Jube” at 35 pounds.[7]

When William Noyes turned 21, entitled to Jube’s half-time service, Jenny was a year old. Perhaps she was the daughter of the Negro woman who served in the family homestead or the sister of Richard Jimmie. After William Noyes married Eunice Marvin (1735–1816) in 1756, Jenny could have moved to their household next door, assigned kitchen and laundry tasks as she grew to womanhood. But the circumstances of her youth cannot be documented. Like her husband Prince (–1791) she may also have been purchased.

Toward Emancipation

Jenny’s children came of age during the years of slavery’s decline. The first law limiting human bondage in Connecticut passed in 1774, three years after her daughter Nancy’s birth. It prohibited the further importation of “Indian, Negro or Molatto Slaves,” stating that “the increase of slaves in this Colony is injurious to the poor and inconvenient.” It also imposed a fine for violations of “one hundred pounds, lawful money, for every slave so imported.” That same year the census counted 3,680 whites and 124 Negroes in Lyme.[8] One in thirty residents was Negro, and a few slaves had been freed.

James Martin, Eunice Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John and Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

James Martin, Eunice Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John and Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

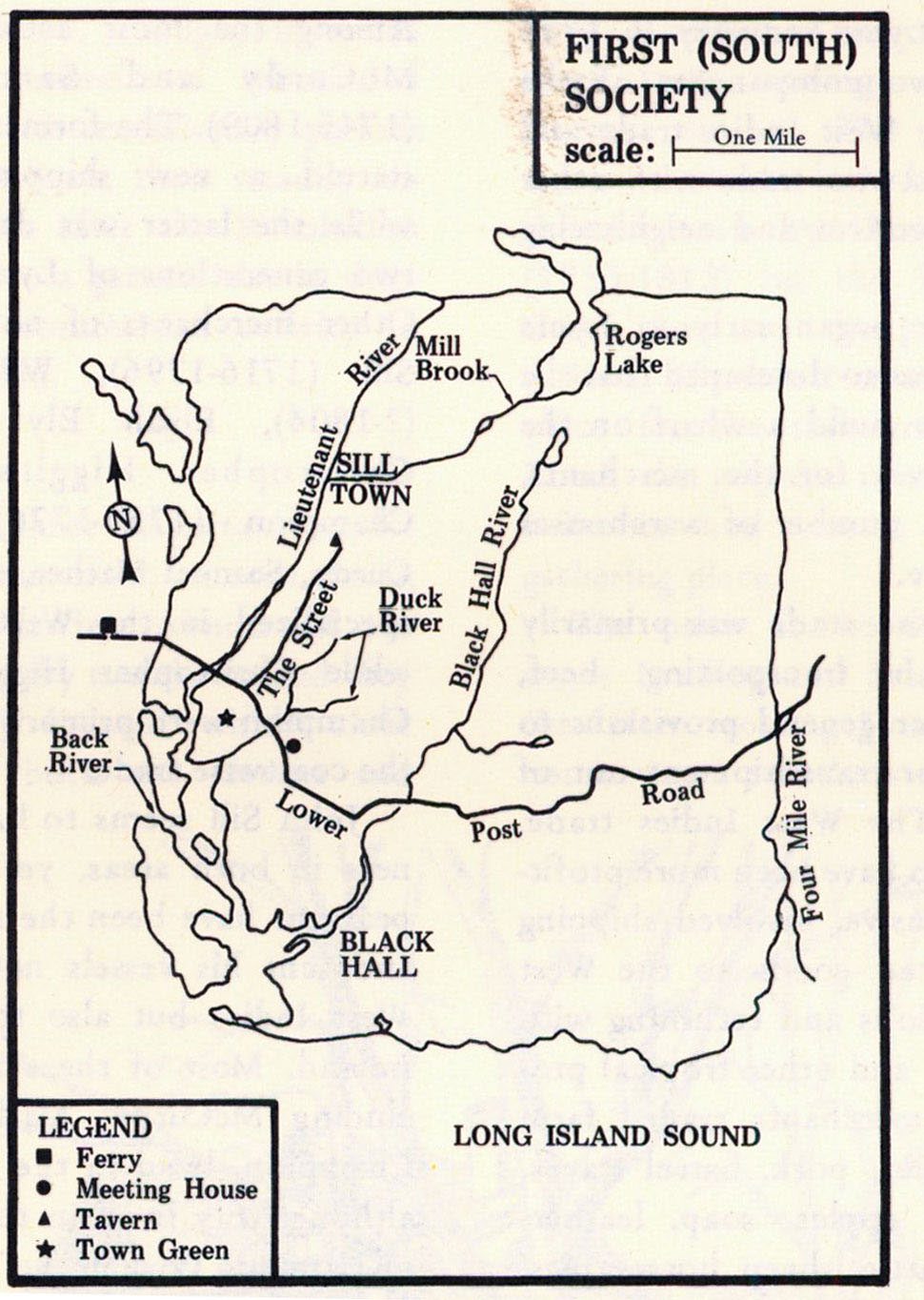

Map detail, First Society. J. David Little, Revolutionary Lyme: A Portrait, 1765-1783

Map detail, First Society. J. David Little, Revolutionary Lyme: A Portrait, 1765-1783

Mary Noyes Ely (1705–1773) was among the earliest to manumit a servant. The death of her first husband Dr. John Noyes (1687–1733), William’s uncle, just a year after their marriage, had left her with two slaves who passed to her second husband in 1736, then became her property again after his death. Her will, written at age 64, stated: “my Negro man Named Warrick should be free after my Decease & I hereby manumit & Sett my Said Negro man Servant after my Death free to be his own man to all Intent & Purposes whatsoever.”[9] By then Warwick had been her “man Servant” for almost forty years.

In 1773 when Warwick (1723–1793) became “his own man” at age 50, the number of slaves in William Noyes’ household was still increasing. Between 1771 and 1780 Jenny bore five children into servitude. The census in 1790 counted five Negro servants in his household and two in the dwellings of each of his sons, Dr. John Noyes (1756–1808) and William Noyes, Jr. (1760–1834). By then Jenny’s youngest child Temperence was ten, and her first grandchild Jordan was three. Whether her husband Prince (–1791) was included in the census count is not known. He may already have gone to sea.

Enterprising merchants like John McCurdy and Samuel Mather, Jr. (1745–1809) owned multiple slaves during the years that Lyme prospered as a center for shipbuilding and maritime trade. Their servants almost certainly performed the heavy work of loading and unloading goods at wharves and warehouses along the riverbanks, and they may also have provided seagoing labor for coastal voyages. After John and William Noyes, Jr., invested in a 48-foot sloop built at the nearby Hill brothers’ shipyard in 1785,[10] the family slave Prince may have gone to sea.

Samuel Mather, Jr., house, ca. 1885. LHSA

Samuel Mather, Jr., house, ca. 1885. LHSA

Jenny’s husband likely served as a deckhand on the sloop Barney’s first commissioned voyage in 1790 commanded by Captain Ezra Lee (1749–1821). Like other Negro seamen still enslaved or recently freed, he would have earned modest pay that could be saved to purchase a plot of land and provide for his family’s future.[11] Manumission documents have not been found for Noyes slaves, but the scrapbook’s inclusion of his surname “Freeman” suggests that he was emancipated before his final voyage. In 1791 he died at sea, leaving Jenny widowed at age 43 with five children and two grandchildren in hereditary servitude.

Jenny’s Progeny

Graves of Judge William Noyes, Mrs. Eunice Noyes, Dr. John Noyes

Graves of Judge William Noyes, Mrs. Eunice Noyes, Dr. John Noyes

Jenny’s children followed different paths through slavery. The census in 1800 counted 4,830 whites, 108 recently freed blacks, and 23 slaves in Lyme. Six of those still in bondage lived in Noyes households. The number of family servants had not changed in 1810, three years after Judge Noyes’ death, when only nine slaves remained in town. But by 1820 Jenny and her progeny[12] had been emancipated. The census that year counted ten “Free Colored Persons” in Noyes households. Three lived with William Noyes, Jr., in the stately new mansion built by Samuel Belcher (1779–1849) that today houses the Florence Griswold Museum.

Florence Griswold house

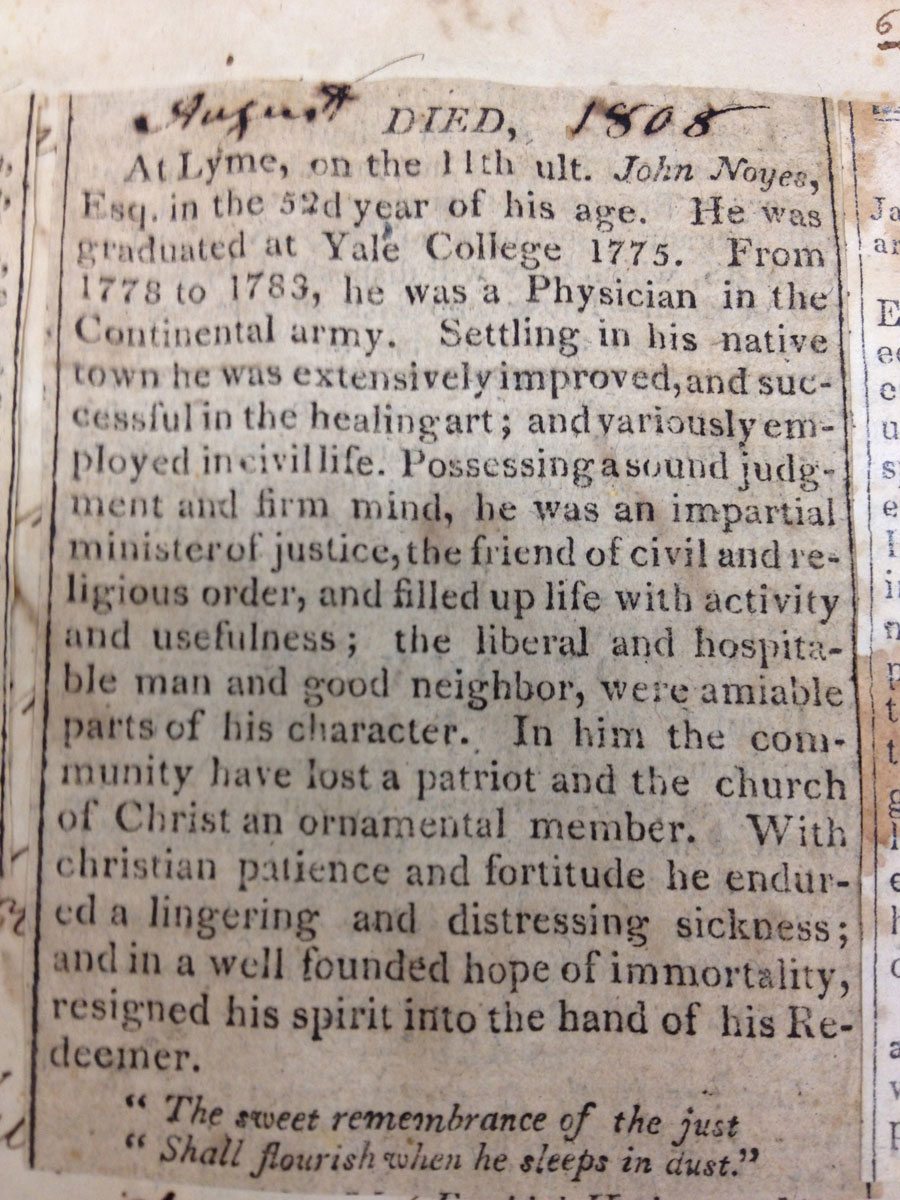

Dr. John Noyes, obituary. LHSA

Dr. John Noyes, obituary. LHSA

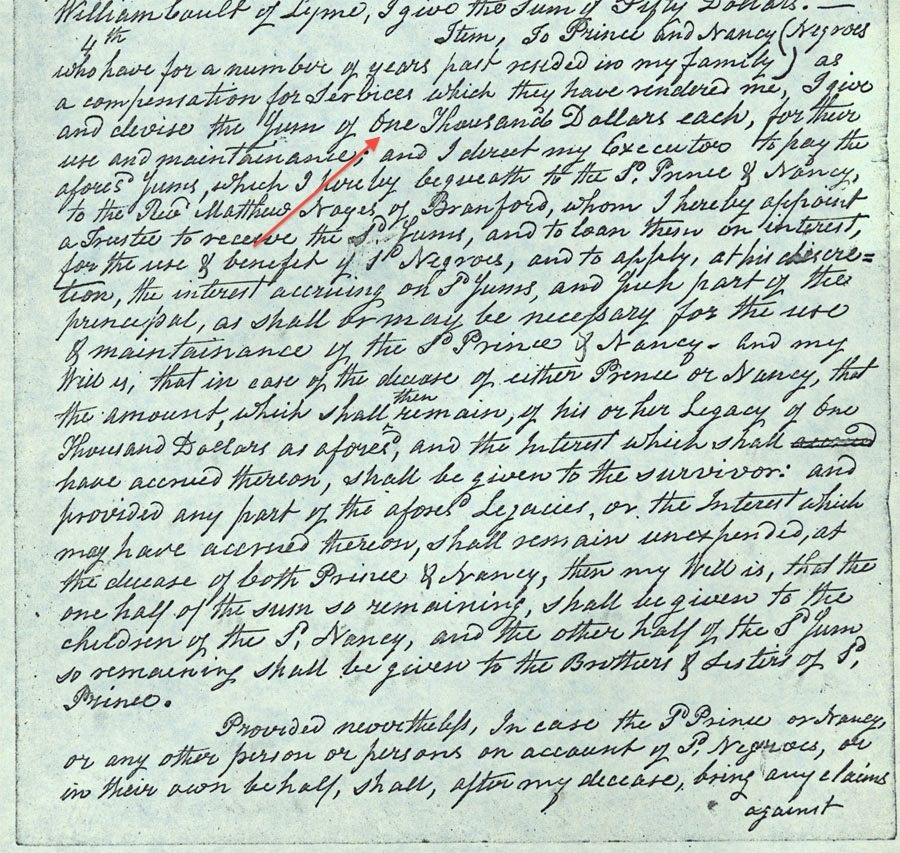

Mary Ann Noyes bequest to Prince and Nancy. LHSA

Mary Ann Noyes bequest to Prince and Nancy. LHSA

Jenny’s oldest child Nancy (1771–1853) resided for many years in what is today the Bee & Thistle Inn on Lyme Street where she served the widow of William Noyes’ eldest son John. In her will Mary Ann Noyes (1768–1819) left to Nancy, for her “use and maintainance,” a generous bequest of $1,000.[13] By then Nancy had three children and three grandchildren, but her life became increasingly troubled with alcohol. Her “intemperance” caused the town a decade later to appoint William Noyes, Jr., as “Overseer” to restrain her financial “miss management.”[14]

Jenny’s elder son Prince (1774–1826), named for his father, also received a generous bequest from Mary Ann Noyes in 1819. He had no known children, and when he died at age 52 in the household of Dr. Richard Noyes (1787–1864), Judge Noyes’ grandson, he was remembered as “a very faithful servant.”[15] By then he had been free for more than six years.

James Martin, Capt. Joseph Noyes, ca. 1798. Photograph. LHSA

James Martin, Capt. Joseph Noyes, ca. 1798. Photograph. LHSA

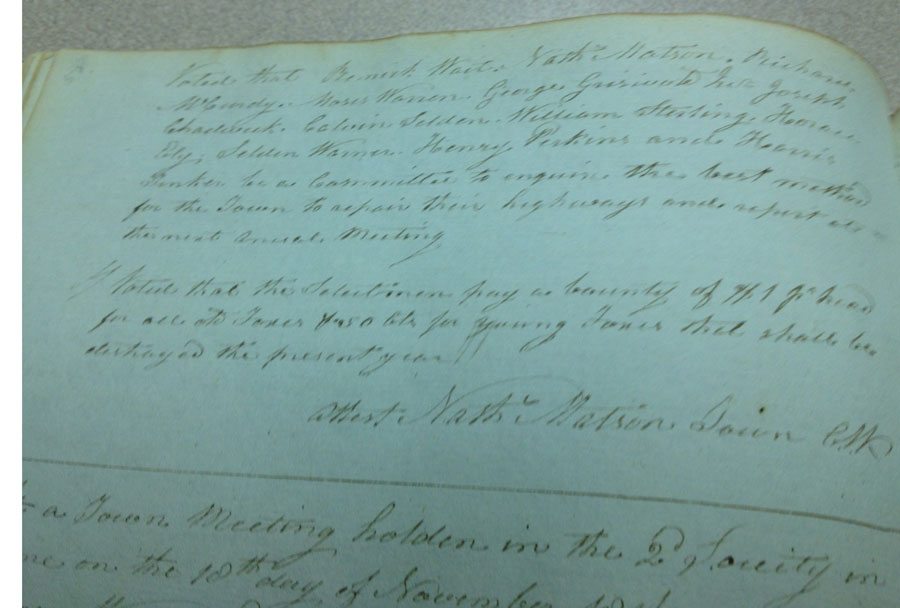

His younger brother Pompey (1776–1822) did not wait to be emancipated but became a fugitive in 1816. That year in June the town paid “a $2.00 bounty to POMP for killing 4 young foxes.” Six months later he fled, and on Christmas day Capt. Joseph Noyes (1758–1820), William Noyes’ second son, placed a notice in the Connecticut Gazette: “Negro man Pomp, ae 40 has run away from Joseph Noyes of Lyme. Pomp is blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other.”[16] When and how Pomp returned is not known, but he apparently died in Lyme. His headstone inscription, now almost obscured, reads: “Pomp Freeman, son of Prince & Jenny, died Aug. 9, 1822, age 46.” A small footstone bears the initials “P F.”

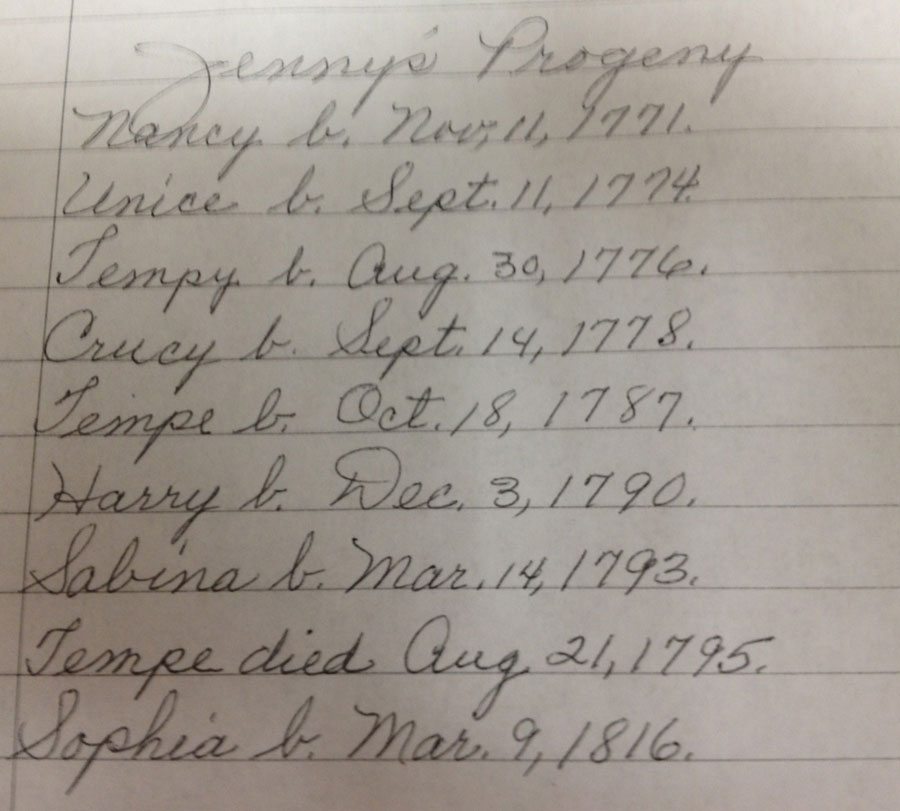

List of “Jenny’s Progeny.” LHSA

List of “Jenny’s Progeny.” LHSA

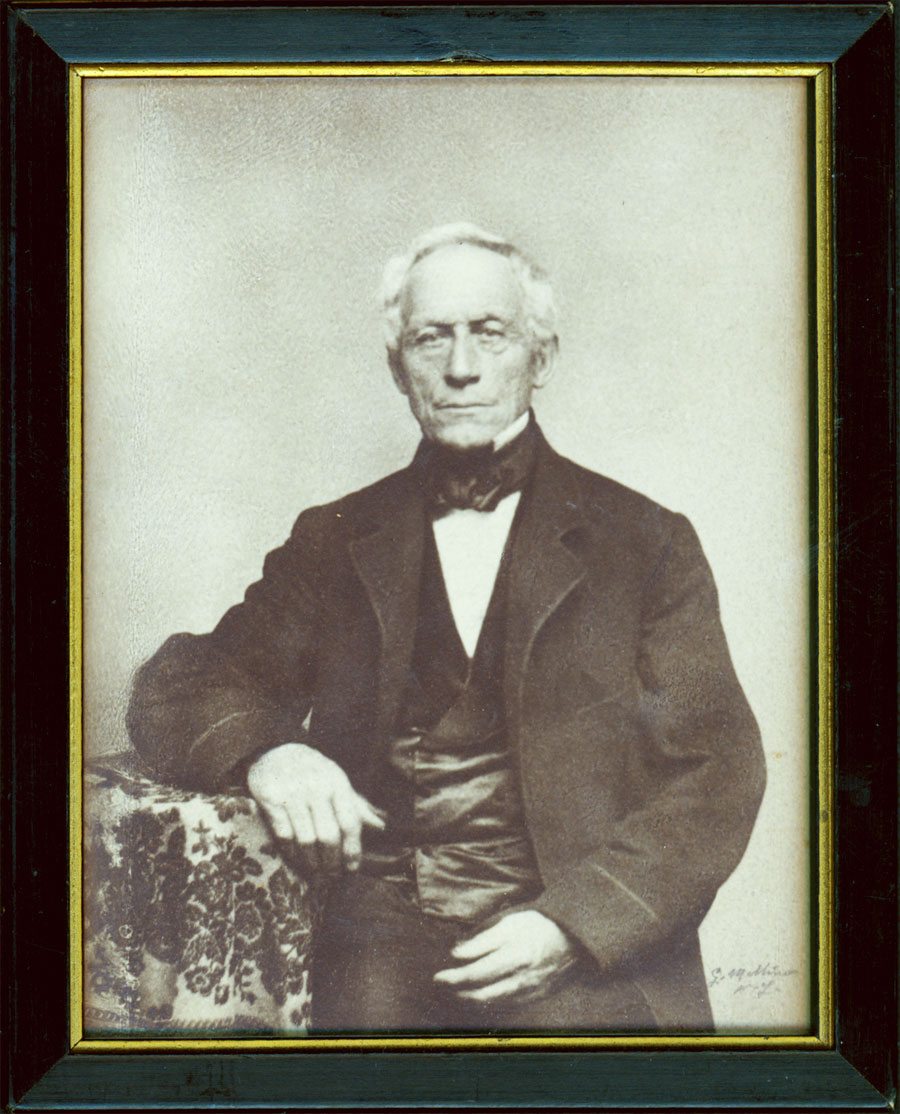

Daniel Rogers Noyes, ca.1870, LHSA

Daniel Rogers Noyes, ca.1870, LHSA

“Voted that the Selectmen pay a bounty of $ 1 pr head for all old foxes & 50 Cts for young Foxes that shall be destroyed in the present year.” Town Meeting Book, 1822

“Voted that the Selectmen pay a bounty of $ 1 pr head for all old foxes & 50 Cts for young Foxes that shall be destroyed in the present year.” Town Meeting Book, 1822

Like many slaves in town, Jenny’s second daughter Crausa (1778-), also called Crucy and Cruse, left few traces. The scrapbook notation of her birth date, her inclusion on a list of “Jenny’s progeny,” and the mention of her name in a family letter are all that confirm her passage through Lyme. She may have been given, or sold, to the family of George W. Noyes (1801–1866) in Stonington. In 1824 the Salem firm of Minard & Noyes, which sold sundries, billed a “colored woman” named Crusa, so perhaps she settled there or nearby.[17]

Jenny’s last child Temperence (1780–1795), called Tempy, died at age fifteen in the town of Durham twenty-five miles from home. The scrapbook leaves the circumstances of her death unclear, but she most likely had been sent to serve the family of John Noyes Wadsworth, Jr., (1758–1814), Judge Noyes’ cousin and a great-grandson of Lyme’s first minister Rev. Moses Noyes (1643–1729). Tempy may have been ill when she set out to visit her mother, or an accident could have interrupted her travel. The scrapbook notes only that she died in Durham in 1798 at the house of Col. Wadsworth “in a journey to Lyme.”

When the younger Prince died in 1826, a family letter described Jenny’s grief. “It is a very heavy stroke to poor Old Jenny,” Daniel Rogers Noyes (1793–1877) wrote to Rev. Matthew Noyes (1764-1839), Judge Noyes’ youngest son who had settled as the Congregational minister in Northford. “She is deeply afflicted & says she little thought she should live to see Prince and so many of her children buried.”[18]

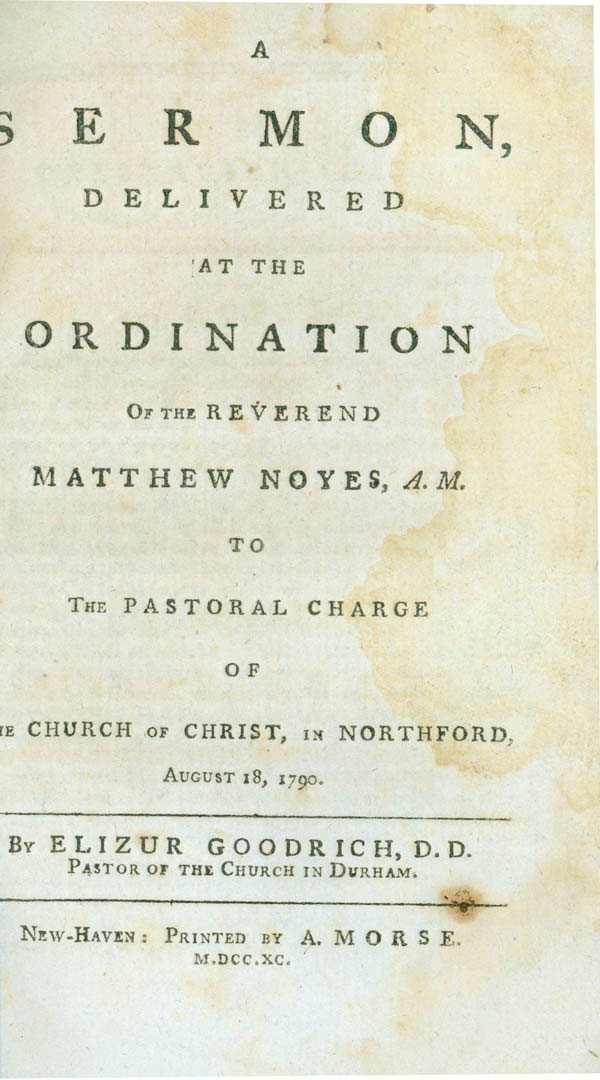

“A Sermon Delivered at the Ordination of the Reverend Matthew Noyes, A. M.”, 1790. LHSA

“A Sermon Delivered at the Ordination of the Reverend Matthew Noyes, A. M.”, 1790. LHSA

A Slave’s Legacy

The last two generations of Noyes family servants came of age as legal emancipation neared. In 1784 the Gradual Emancipation Act, which freed slaves born after that date when they turned 25, required that their births be registered. Judge Noyes accordingly documented Jenny’s first grandchild: “This certifies to the best of my knowledge that my Negro Boy called Jordan was born the 18th day of November AD 1787.” When the Negro boy was six weeks old, “William Noyes Esq. had personally appeared on December 31, 1787, and made Oath to the above Certificate.”[19]

Jordan reached the age of emancipation in 1812, followed soon by his siblings Harry and Sabina. But when Jenny, age 84, died “of a cancer” in 1832, slavery still had not been abolished in Connecticut. Another sixteen years would pass before the state prohibited all human bondage in 1848.

Slavery lingered in the memory of Judge Noyes’ descendants. His son William Noyes, Jr., likely provided the information preserved in the scrapbook, but Jenny also left more tangible traces. Ellen Noyes Chadwick, an accomplished Lyme artist, saved Jenny’s “black ivory heart-shaped knitting sheath,” and Dr. Richard Noyes, who practiced medicine in town for many years, kept her small black teapot.[20]

Dr. Richard Noyes house

Dr. Richard Noyes house

[1] The scrapbook has an interesting history. It appears to have been started by Mary Ann Noyes Learned, daughter of William Noyes 3rd and Hannah Townsend Noyes. When she left her home in what is now the Florence Griswold Museum and moved with her family to Albany in 1837, the scrapbook remained in Lyme. It later passed to her cousin Martha Noyes, also a great-granddaughter of Judge William Noyes. The youngest child of Sgt. Enoch and Clarissa Dutton Noyes, Martha died of consumption at age 41 and was remembered as “a fine musician, with much general ability, including a poetic gift.” See Edward and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, Family Histories and Genealogies (New Haven, 1892), I:320. A photocopy of Ellen Noyes Chadwick’s notes on family history is in Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6, LHSA.

[2] Charles J. Hoadley, ed, The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, from May 6 1751, to February, 1757, Inclusive (Hartford, 1877), 10:617. The 1756 census also counted 94 Indians in Lyme.

[3] Martha J. Lamb, “Lyme: A Chapter in American Genealogy,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LII (February 1876), p. 318. Monographs G-Lu, LHSA.

[4] Jackson Turner Main, “The Economic and Social Structure of Early Lyme,” in George J. Willauer, Jr., ed., A Lyme Miscellany, 1776–1796 (Middletown, 1997), pp. 44-45; Family Histories and Genealogies, I:138.

[5] New London Summary, October 10, 1760. Cited in Barbara W. Brown and Joseph M. Rose, Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650–1900 (New London, 2001), p. 604. For a discussion of the slave trade in New London, see Allegra di Bonaventura, For Adam’s Sake: A Family Saga in Colonial New England (New York, 2013), pp. 44-45.

[6] Connecticut Courant, September 22, 1766. Cited in “Their Own Stories: Voices from Middletown’s Melting Pot,” Middlesex County Historical Society.

http://www.middlesexhistory.org/exhibits/africans.htm

[7] New London County Probate Records 1744, #3846. Photocopy in Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6, LHSA.

[8] Hoadley, Public Records, 14:329, 487. The 1774 census also counted 104 Indians in Lyme.

[9] New London County Probate Records 1773, #1930.

[10] Thomas A. Steeves, Old Lyme, A town inexorably linked to the sea: A Maritime History (Deep River, 1959), p 14; Connecticut Ship Database, 1789–1939, Mystic Seaport.

http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/CuVessel.cfm?VesselId=100788

[11] Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, 1997), p. 4.

[12] Local historian and Noyes descendant Susan Hollingsworth Ely (1905–1986) compiled a list of “Jenny’s Progeny” ca. 1970. Photocopy, LHSA.

[13] Will of Mary Ann Noyes, September 15, 1819. New London County Probate Records; photocopy, Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6.

[14] Appointment of Overseer, April 6, 1829. Courtesy Lyme Public Hall.

[15] Daniel R. Noyes to Revd M. Noyes, February 1, 1826, LHSA.

[16] Lyme Treasurer’s Records, Connecticut State Library; Connecticut Gazette, December 25, 1816, cited in Brown and Rose, p. 272.

[17] Between 1824 and 1826 Nathan Minard (1788–1878) of Salem and George W. Noyes of Stonington, jointly owned the general merchandise company Minard & Noyes. See Brown and Rose, p. 483.

http://books.google.com/books/about/Minard_Companies_Account_Books.html?id=3TUzkgAACAAJ

[18] Daniel R. Noyes to Revd M. Noyes.

[19] Verne M. Hall and Elizabeth B. Plimpton, eds., Vital Records of Lyme, Connecticut, to the End of the Year 1850 (Lyme, 1976), pp. 69-70.

[20] Ellen Noyes Chadwick, Notes on family history.