by Carolyn Wakeman

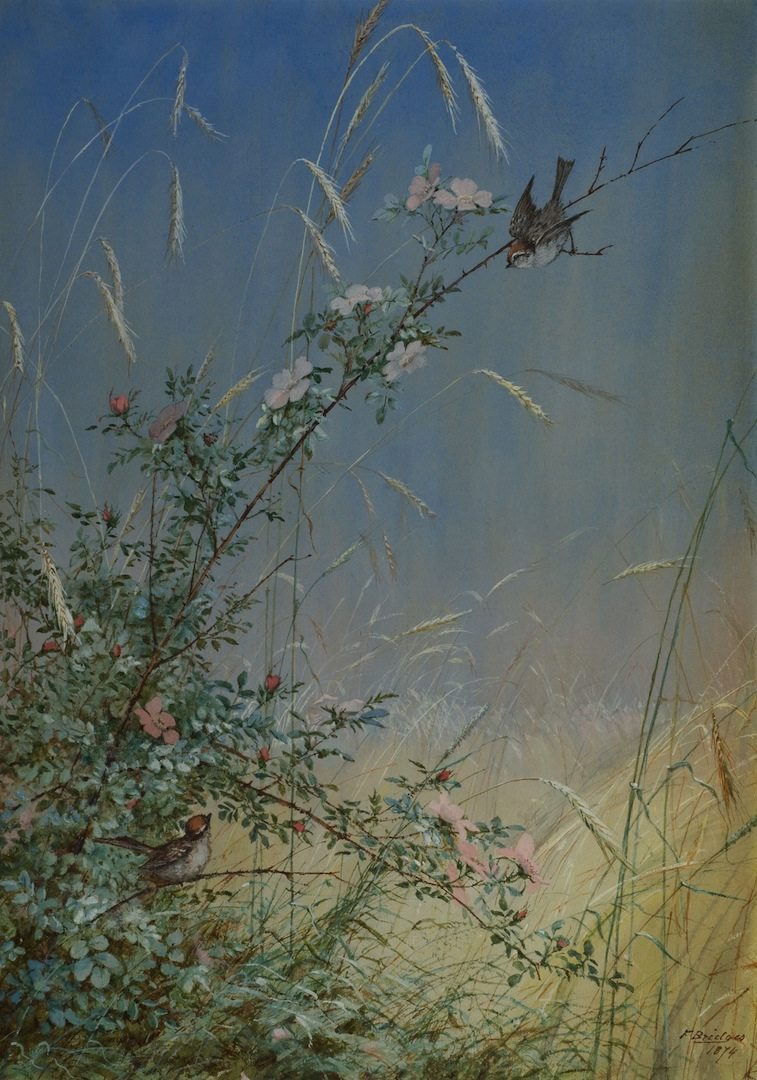

Feature Image: Fidelia Bridges, Wild Roses Among Rye, 1874. Watercolor and gouache over pencil. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Picturesque Neighborhood

The elegantly drawn botanical studies by Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923) featured in the Florence Griswold Museum’s stunning summer 2017 exhibition Flora/Fauna: The Naturalist Impulse in American Art highlight the experience of an exceptionally talented American watercolorist during three formative summers sketching and painting in Old Lyme. “Artists are beginning to find the picturesque attractions of the neighborhood,” local painter Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824–1900) wrote to historian Martha J. Lamb (1829–1893) in 1874. “Miss Fidelia Bridges, after spending last summer near the lakes in the center of the town, came again this year, and expects to make it a special summer resort for the prosecution of her beautiful art.”[1]

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Rogers Lake, 1876. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Rogers Lake, 1876. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. LHSA

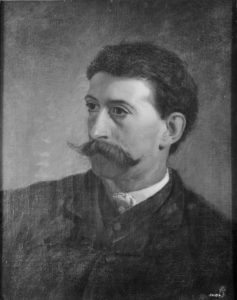

The importance of Old Lyme as a setting for Miss Bridges’ studies of wildflowers, grasses, and birds has not yet been noted. Accounts of her artistic career uniformly describe Stratford as the location for her graceful nature sketches during the mid-1870s. But letters and newspaper columns document extended periods when she painted fifty miles east along the shoreline on visits to the family home of New York portrait painter Oliver Ingraham Lay (1845–1890). “Lyme has attracted the attention of several artists,” The New Haven Register reported in 1882. Miss Fidelia Bridges “from the suggestion of O. I. Lay took a house here a few years since and found abundant opportunities for her lovely foreground water-color drawings.”[2]

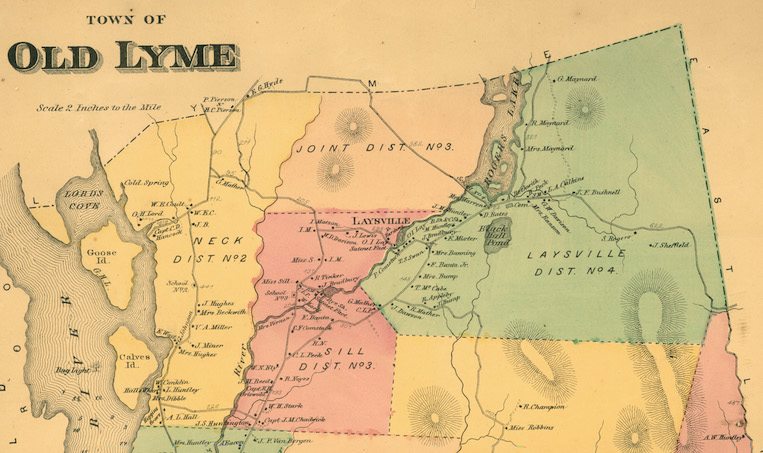

Town of Old Lyme. F. W. Beers, 1868, LHSA

Assertions that Fidelia Bridges “introduced Oliver Lay to the pleasures of Connecticut”[3] ignore the portraitist’s longstanding ties to Old Lyme where his ancestor John Lay (1633–1696) settled in the 1650s. Members of the Lay family remained substantial property owners in the town for more than two centuries, and Oliver Lay spent all his boyhood summers in the section north of the village called “Laysville.” There his father’s brother Squire Oliver Ingraham Lay (1799–1876), for whom he was named, erected a handsome stone mill in 1839 and served for many years as judge of probate. Young Oliver began recording his sketches in Laysville at age fifteen. “Made a study of a tree on canvas 9 x 11 not very good, finished May 25th back of [Marvin] Huntleys with water &c,” he wrote in a notebook that would chronicle his artistic efforts between 1861 and 1898.[4]

Stone mill, Laysville, ca. 1839. Postcard, LHSA

Brooklyn Friendship

Fidelia Bridges had already made sketching trips with her Philadelphia mentor William Trost Richards (1833–1905) to Lake George and the Lehigh Valley by the time she met Oliver Lay in Brooklyn in 1865. A carte de visite photograph likely taken the previous year shows her posed with a wooden paint box and a folding umbrella against a rocky woodland backdrop. Her early paintings in oil, portrait-like studies of the natural world, display an intimate, often exuberant, observation of landscape details. After traveling for a year in Europe, she returned to Brooklyn in 1868 and resumed work in her studio along with her friendship with Oliver Lay. In 1871 she began working primarily with watercolors.[5]

Carte de visite photograph of Fidelia Bridges, ca. 1865

Fidelia Bridges, Still Life with Robin’s Nest, 1863. Oil on wood, private collection

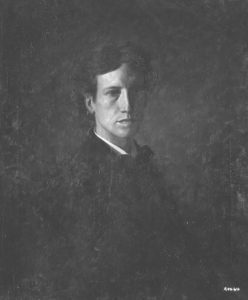

Mr. Lay painted his first portrait of Fidelia Bridges the next winter, six months before her initial summer in Old Lyme. “I am proud of my success with Fidelia’s portrait,” he wrote in December to Phoebe Brown (1823–1903), wife of William Augustus Brown (1817–1891) in whose Brooklyn home the two young painters had first met. “I have grown so that I can carry out the vision of the picture I see. I know it will have some angelic trait.”[6] Lay’s record book notes that Miss Bridges posed in a black dress “with arms folded and one hand opening,” and in May 1873 when she was elected a National Academy of Design associate, she presented Oliver Lay’s likeness “as her Academy portrait.”[7] Two months later in July she took the train to Old Lyme, which became her “special resort for the prosecution of her beautiful art.”

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Fidelia Bridges, 1872. Oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Oliver Lay almost certainly described to Fidelia Bridges the natural beauty and abundant bird life of his family’s Connecticut home. He had mentioned to a cousin in 1871 his own eagerness “to make an album of Lyme sketches—say a picture of the Factory and Hardings house and the brook and the school house with Grassy Hill in the distance and a huckleberry scene with Aunt Lynda & Uncle Prentice [Comstock]… don’t you think they’d be interesting? I’ve had them on my mind for some time.”[8] In 1872 he completed a series of detailed pencil studies of the imposing rock clusters near his Uncle Oliver’s factory as well as the salt box-roofed home of his grandfather David Lay (1769–1843).

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Rocks over beyond Hardings, 1872. Pencil on paper, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of George C. Lay

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Grandpa Lay, 1872. Pencil on paper, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of George C. Lay

Sketching in Laysville

During the summer of 1873 and again in 1874, Fidelia Bridges pursued “her lovely foreground water-color sketches” in Old Lyme. Critics expressed admiration for the paintings she submitted to the American Watercolor Society’s exhibition in February 1875. “Too much praise cannot be awarded Miss Fidelia Bridges for her beautiful studies of ‘The Edge of a Pasture,’ ‘Catkins,’ and others,” one reviewer stated. “Miss Bridges apparently selects the most commonplace subjects, and yet, by her pleasant manner of treatment, transforms them into interesting pictures.”[9]

Buyers as well as critics admired her luminous images of meadows and marshlands, and her sketches commanded higher prices at the 1875 exhibition than submissions by fellow watercolorists like Winslow Homer (1836–1910). While her paintings sold for $200, works by Homer, who had been admitted to the National Academy of Design in 1865, were priced between $25 and $100.[10] “Miss Bridges is unquestionably one of the most successful of our local artists,” a writer for the Brooklyn Eagle commented in July 1874 while she was working in Old Lyme. “Her pictures appear to have struck the popular fancy, and as a natural result, she has enjoyed a busy as well as profitable year.”[11]

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Winslow Homer, 1865. Oil on canvas, National Academy Museum and School

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Winslow Homer, 1865. Oil on canvas, National Academy Museum and School

An invitation to exhibit three paintings at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 enhanced Fidelia Bridges’ already prominent reputation. “Her works are like little lyric poems,” landscape artist John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872) had written the previous year, “and she dwells with loving touches on each of her buds, ‘like blossoms atilt’ among the leaves.”[12] Although Miss Bridges rarely identified the settings of her paintings, “A Kingfisher and Catkins” and “Corner of a Rye Field,” exhibited in Philadelphia, could well have been sketched along the Mill Pond near Oliver Lay’s family home. Two months after the Philadelphia Exhibition opened in May, she returned for her last summer in Old Lyme and settled again into a rented house near scenic Rogers Lake.

The Road to Rogers Lake, postcard. Postmarked 1911, LHSA

The Road to Rogers Lake, postcard. Postmarked 1911, LHSA

Summer Portfolio

Aided by a faithful servant Hannah Fry “and a younger Fry,” Fidelia was also accompanied during the summer months of 1876 by her older sister Elizabeth Bridges (1831–1882) and “their great Maltese cat” who, Mr. Lay noted, had landed safely “after hours of anxious solicitude on the cars.” The sisters “are taking life as comfortably as they can,” he added in a letter to a mutual friend.[13] On daily visits he offered assistance and encouragement after Fidelia had trudged through meadows and rowed under a hot sun along the lakeshore. “I keep at work grinding out picture after picture after picture in such constant succession that I begin to feel like a picture machine,” she wrote to her friend Anna Brown.[14]

Fidelia Bridges, Milkweeds, 1876. Watercolor on paper, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute

Fidelia Bridges, Milkweeds, 1876. Watercolor on paper, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute

“Miss Bridges Portfolio is filling up beautifully,” Mr. Lay remarked in July. “Young ladies say to her ‘How I do envy you Miss Bridges’…. but if they could see her I’m sure they wouldn’t,” he wrote. “She sits for days in the hottest breezeless corners of fields working, or in a boat with the reflected sun glaring up under her umbrella from the calmest of dead waters, and all the time she has the same delicate grace of manner & speech as if she was in her own parlour.” Watching Fidelia work reinforced his own preference for portraiture. “I never realized before the difficulties of a landscape-painter’s life,” he said, “and I am thankful I don’t paint them.”[15]

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Self Portrait, 1876. Oil on canvas, National Academy Museum and School

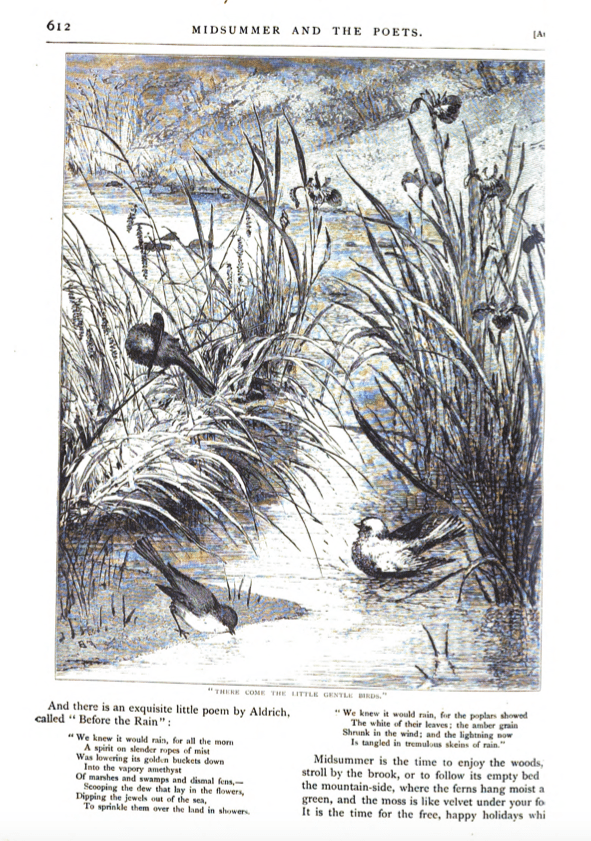

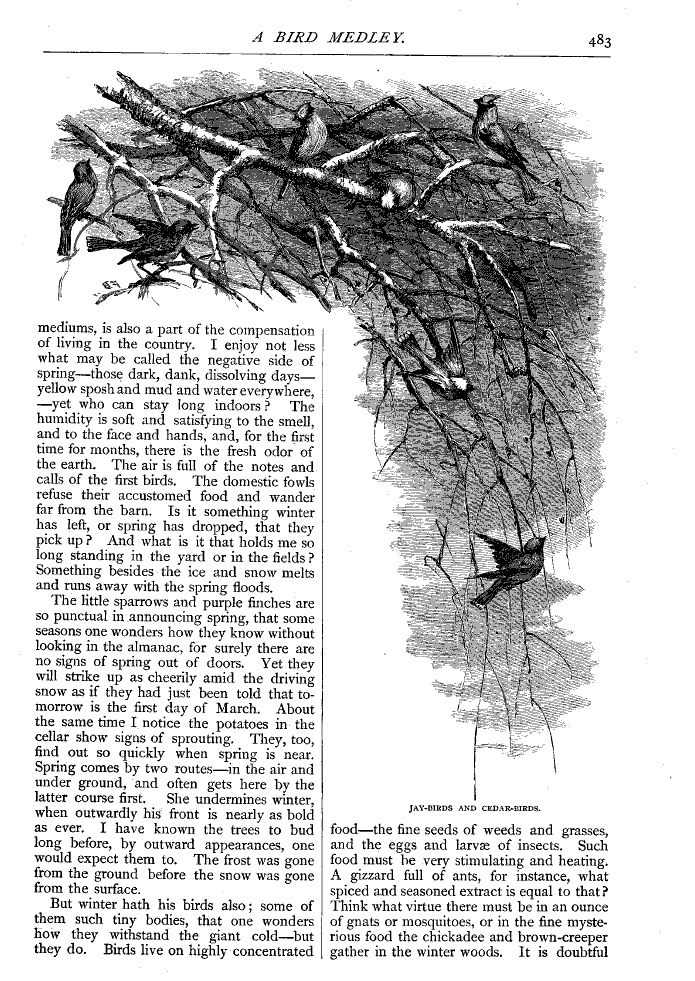

After Mr. Lay left Lyme in August 1876 for a portrait assignment up the Hudson, he wrote to their mutual friend that he quite missed the Misses Bridges, “for we did a great deal of walking and boating together.” He also expressed his admiration for her recent achievement. “You will be delighted to see her summers work,” he told Mr. Walker. “She is doing better than ever and finds Lyme quite full of subjects.” She had also found new outlets for her sketches. The previous month her delicately expressive bird studies had appeared in Scribner’s Magazine to illustrate an article by literary naturalist John Burroughs (1837–1921). “I am glad you saw the illustrations in Scribners,” Mr. Lay wrote. “I think they are quite beautiful, there is one in St. Nicholas for July and others to follow. I thank you for your offer to send me one but I have mine which I intend to keep.”[16] St. Nicholas Magazine, launched by Scribner’s for a youth audience, had published in August a sketch by Fidelia Bridges to accompany a summer feature article that introduced children to nature poetry.

Fidelia Bridges, “Jay-birds and Cedar-birds,” Scribner’s Magazine (August 1876), p. 483

Fidelia Bridges, “Jay-birds and Cedar-birds,” Scribner’s Magazine (August 1876), p. 483

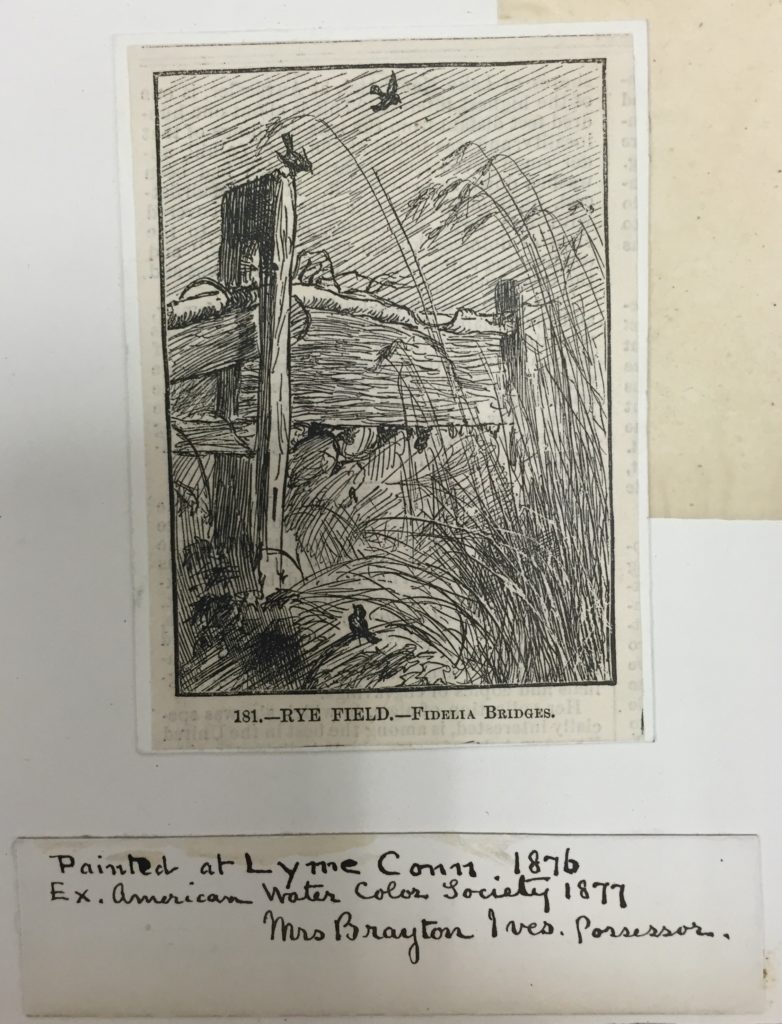

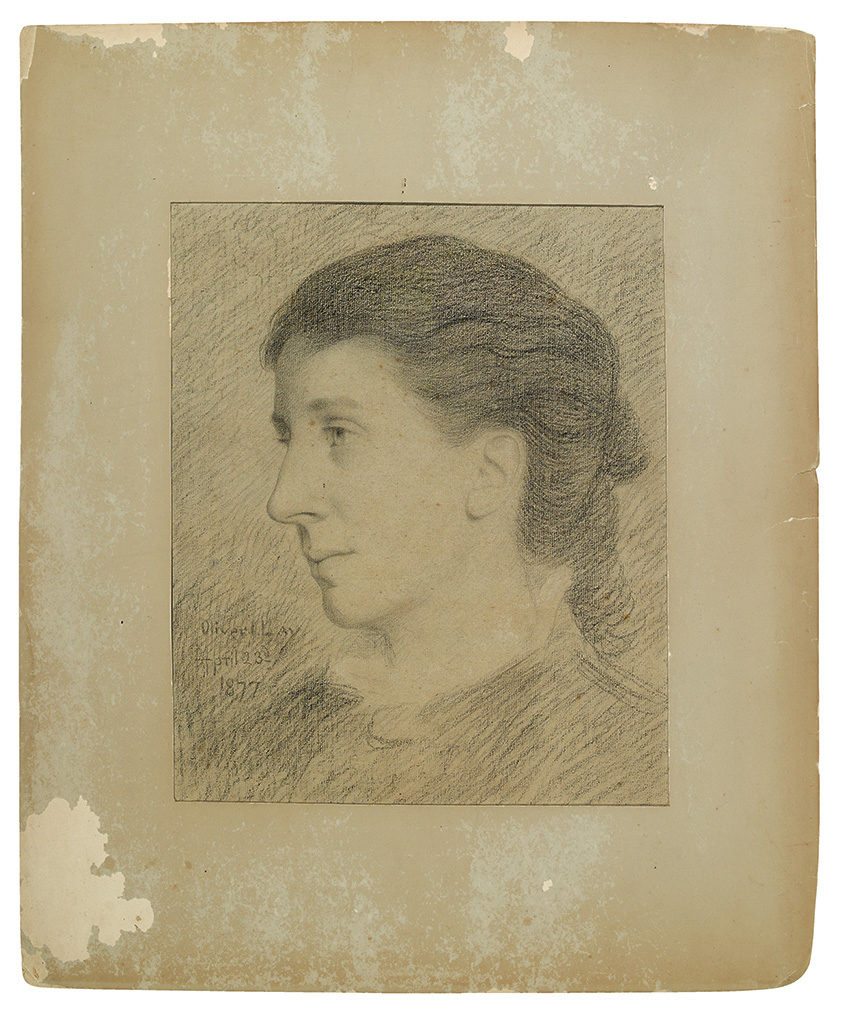

Fidelia Bridges, “There Come the Little Gentle Birds,” St. Nicholas Magazine (August 1876), p. 612

Miss Bridges spent the summer of 1877 in Stratford where Mr. Lay’s mother’s family had a home along the Housatonic River, but the work she submitted to the American Water Color Association’s exhibition that year included at least one work from her Lyme portfolio. Rye Fields, a graceful sketch of grasses and birds beside a rail fence, was “painted at Lyme 1876.” She also identified the Lyme location of two watercolor sketches included in a retrospective exhibition of her work in 1879 at Gustav Reichard’s Art Rooms, a Fifth Avenue gallery. “Sketch. Rogers Lake, Lyme,” which was priced at $25, did not sell, and she shipped “A Mill Pond, Lyme,” priced at $70, to London for an upcoming exhibition at the Dudley Gallery.[17] She spent almost a year in England visiting her younger brother Henry Bridges (1835–1920), then returned to Stratford where Oliver Lay and his family joined her for the summer of 1880. “Miss Fidelia Bridges has been in Stratford some two weeks,” he wrote on July 25. “She boards about a mile away and we see her daily.”[18]

Fidelia Bridges, Rye Fields, 1876. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of George C. Lay

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Fidelia Bridges, 1877. Pencil on paper. Courtesy Swann Auction Galleries

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Fidelia Bridges, 1877. Pencil on paper. Courtesy Swann Auction Galleries

Later Portraits

Even after Oliver Lay started spending summers in Stratford, he continued to paint in Laysville. When he settled into his Uncle Oliver’s house in 1882, The New Haven Register reported on July 22 that “the New York artist Oliver Lay is visiting his father’s native place.” A letter to his wife Marian Wait Lay (1845–1890) described how much he enjoyed staying in his uncle’s place and how he rose early every morning to work on a portrait of his aunt Lucy Lay Banning (1811–1899). “Of course the work is a great responsibility,” he said. “I have begun very slowly but I see not why it will not be successful.” He thanked his wife for visiting Fidelia in Stratford and, eager for Marian to join him in Old Lyme, assured her: “Everything is going with a poetic charm.”[19]

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, 1880. Smithsonian American Art Museum

Oliver Lay painted a second portrait of Fidelia Bridges in 1883 not long after the death of her sister Elizabeth. Miss Bridges sat for her friend in an elegant black dress accented with gracefully draped lace at the neck and wrists, gazing pensively into the distance. Apparently because of the portrait’s size, the National Academy of Design refused the painting for its spring exhibition. Mr. Lay’s record book notes that he took it back and cut down both the canvas and the frame. The eloquently expressive portrait of Fidelia Bridges, age 49, appeared in the Academy’s fall 1884 exhibition.

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Fidelia Bridges, 1883. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum

Oliver Ingraham Lay, Fidelia Bridges, 1883. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum

[1] Special thanks to curator Jennifer Stettler Parsons for generous assistance. Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Martha J. Lamb (Coleman), November 5, 1874, in Martha J. Lamb Papers, New York Historical Society.

[2] See, for example, Frederic A. Scharf, “Fidelia Bridges,” in Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary (Cambridge, MA, 1971), p. 237: “In June 1871 Miss Bridges discovered at Stratford a congenial combination of meadows, flats, and wild flowers [and] for the next seven years she summered in Stratford, as did Oliver I. Lay, a Brooklyn friend and artist.” Also see Katherine E. Manthorne, “’The Voice of Nature’: The Art of Fidelia Bridges in the 1870s” (American Arts Quarterly, Winter 2012): “The watercolors she created over the subsequent five summers [in Stratford] document the development of a signature subject and the refinement of her approach to composition.” A Swann Gallery catalogue states: “From 1871 to 1877, she summered in Stratford, CT, where she became good friends with Oliver Ingraham Lay (1845–1890) and his family.” http://catalogue.swanngalleries.com/asp/fullCatalogue.asp?salelot=2391++++++62+&refno=++706443&saletype

Old Lyme continued to be referred to as “Lyme” after the southern portion of the original town officially separated in 1857.

[3] David Bernard Dearinger, Paintings and Sculptures in the Collection of the National Academy of Design, 1826–1925 (Hudson Hills, 2004), p. 351.

[4] Oliver Ingraham Lay, Record of His Works, 1861-89 (hereafter Record), filmed 1972 by the New-York Historical Society. Photocopy, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA).

[5] Kathleen A. Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent (Philadelphia, 2017), pp. 156-157.

[6] Oliver I. Lay to Mrs. Brown (New York, December 23 [1872]. Photocopy, LHSA.

[7] Oliver Ingraham Lay, Record, #206.

[8] Oliver Lay to Cousin Frances, New York, March 2, 1871. Photocopy, LHSA.

[9] “American Society of Painters in Water-Colours,” Art Journal (1875), p. 92.

[10] Catalogue of the Eighth Annual Exhibition, American Society of Painters in Watercolors, Held in the Galleries of the National Academy of Design (February 1875), pp. 6 ff.

[11] “Fine Arts: Miss Fidelia Bridges,” Brooklyn Eagle (July 30, 1874), p. 3.

[12] “Women Artists,” Art Journal (1875), p. 64, cited in Foster, p. 423, n. 21. See also Charlotte S. Rubenstein, American Women Artists: From the Early Indian Times to the Present (New York, 1982), p. 62.

[13] Oliver I. Lay to Mr. Walker, Lyme, Conn., July 9, 1876. Photocopy, LHSA.

[14] Fidelia Bridges to Anna Brown, April 5, no year, cited in May Brawley Hill, Fidelia Bridges: American Pre-Raphaelite (Berry-Hill Galleries, 1981), p. 23. The author states the letter was written “probably 1873 or 1874.”

[15] Oliver I. Lay to Mr. Walker, Lyme, Conn., July 16, 1876. Photocopy, LHSA.

[16] Oliver I. Lay to Mr. Walker, Red Hook, NY, August 20, 1876. Photocopy, LHSA.

[17] Oliver Lay’s Account Book includes a handwritten list of the 57 sketches and paintings Fidelia Bridges displayed at the Fifth Avenue gallery and notes both prices and purchasers. LHSA. See also Foster, p. 159.

[18] Oliver I. Lay to My dear friend (Walker), Stratford, July 25, 1880. Photocopy, LHSA

[19] Oliver I. Lay to Marian, Lyme, Conn., July 2, 1882. Photocopy, LHSA.