by Carolyn Wakeman

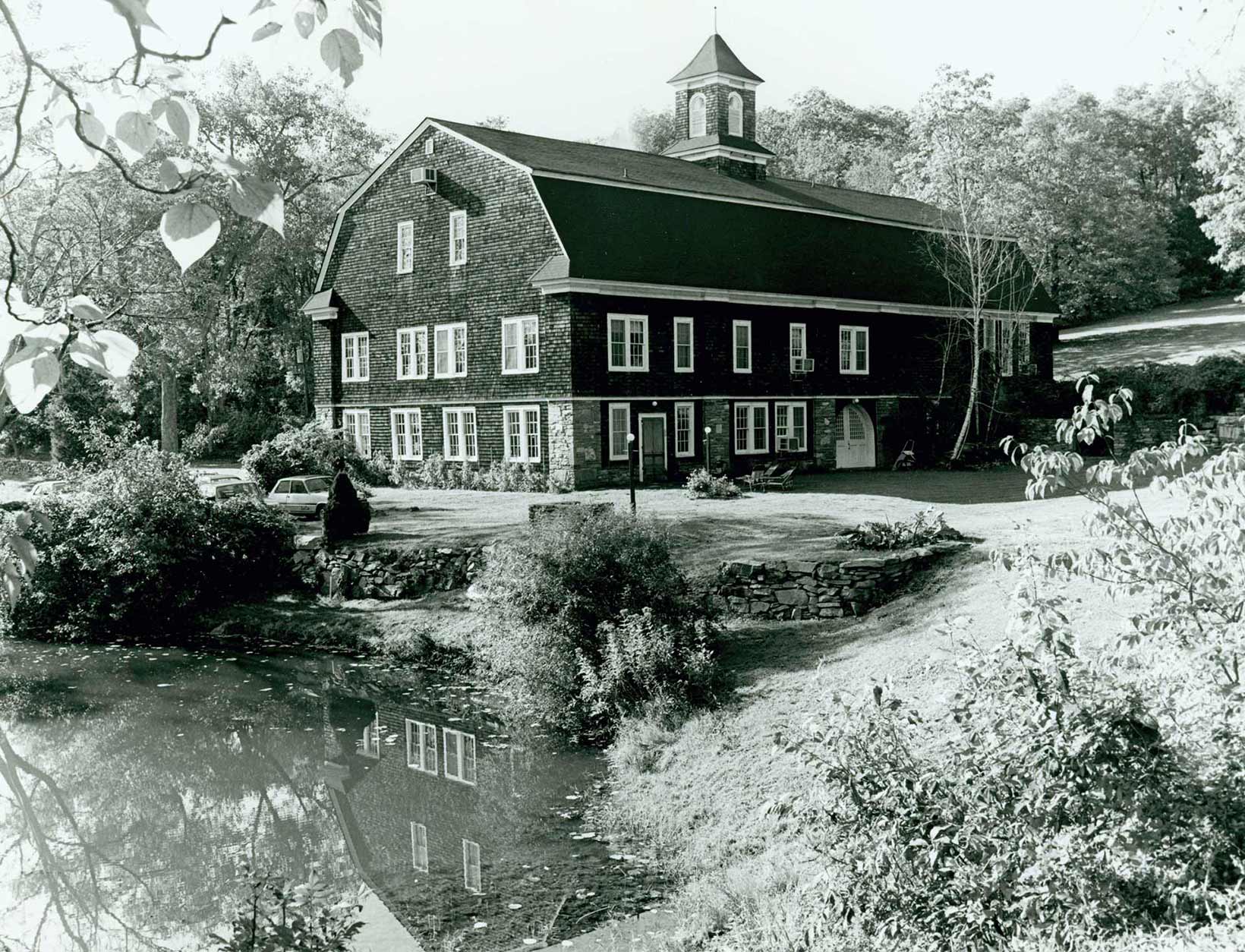

Featured Image(above): Renate Ponsold, View of Harry Holtzman’s home, Lyme, 1984

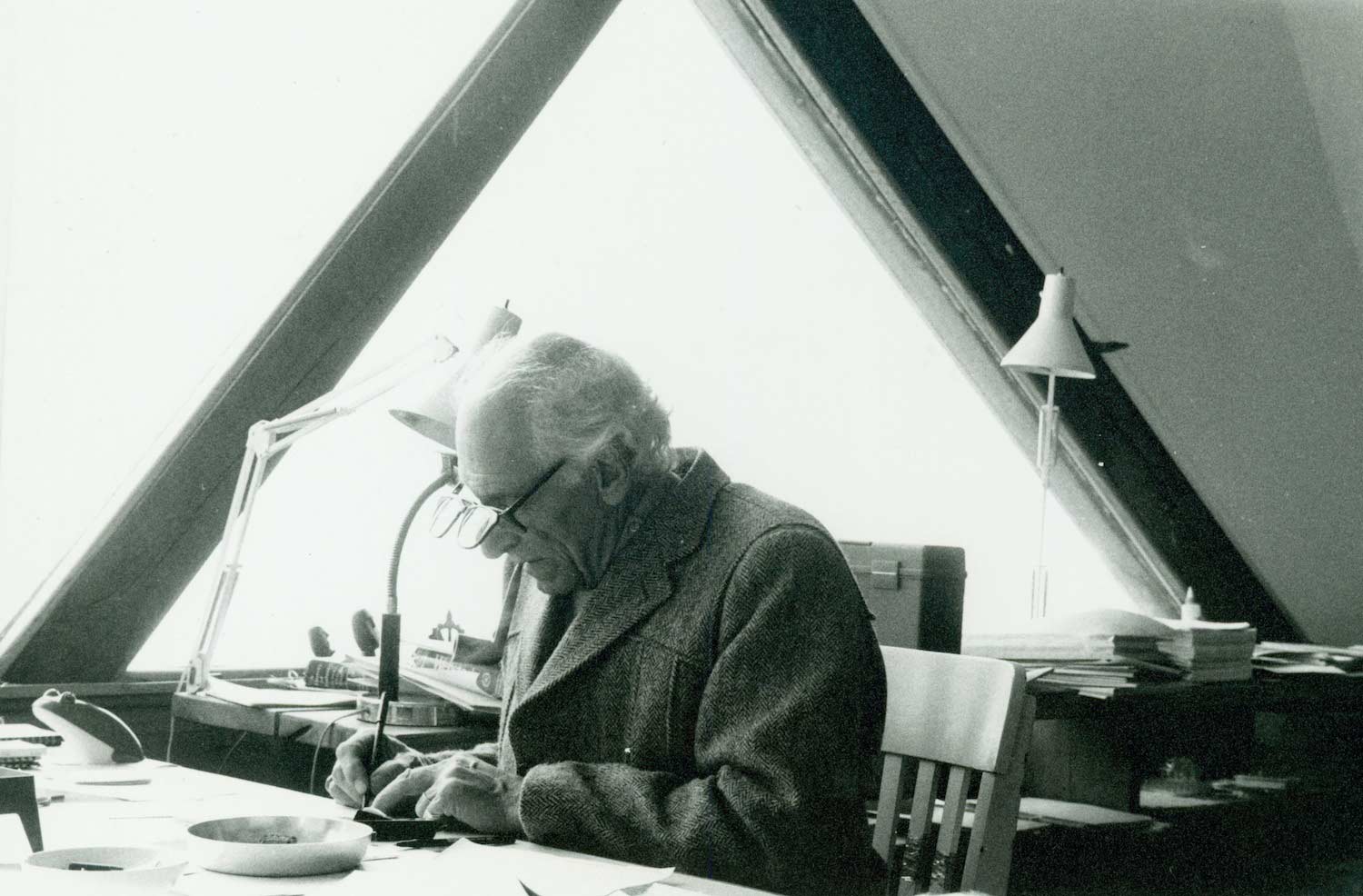

Surrounded by sweeping views of Hadlyme’s meadows and rock-strewn hillsides in a spacious studio created from a former stock barn, New York artist Harry Holtzman (1912-1987) created many of the pioneering modernist works displayed in the Florence Griswold Museum’s exhibition Harry Holtzman and American Abstraction. Stones collected nearby anchor his sculptural compositions quite literally in the Lyme landscape.

Holtzman’s Studio

It was the size and scale of the deteriorating barn on Joshuatown Road that attracted Holtzman on a visit to Lyme in 1962. Even with brambles blocking the doorways, he decided within days to purchase the massive shingle and stone structure on a 3.4-acre plot for ten dollars from then-Connecticut State Police Commissioner Leo J. Mulcahy. Four hired high school students helped him clear away the brush.

Allen Buck, Harry Holtzman in his studio, 1985.

Transforming the 100 x 50 x 64-foot barn into a combined living and studio space took Holtzman more than a year. After creating a central flue from the hay chute, he constructed huge stone fireplaces in each of three outsized living areas. Gradually the calving pen on the first floor became a kitchen, the horse stalls on the second floor became a living room and studio, while the upper hayloft provided storage space. Holtzman called his reclaimed Hadlyme home “Bull Run Hill.” [1]

Harry Holtzman, Open Relief, 1983. Oil on wood with stone. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift Elizabeth McManus, 2013.10

“Gentleman’s barn” in Hadlyme, 2013

Renate Ponsold, Harry Holtzman’s studio with sculptures, Lyme, 1984

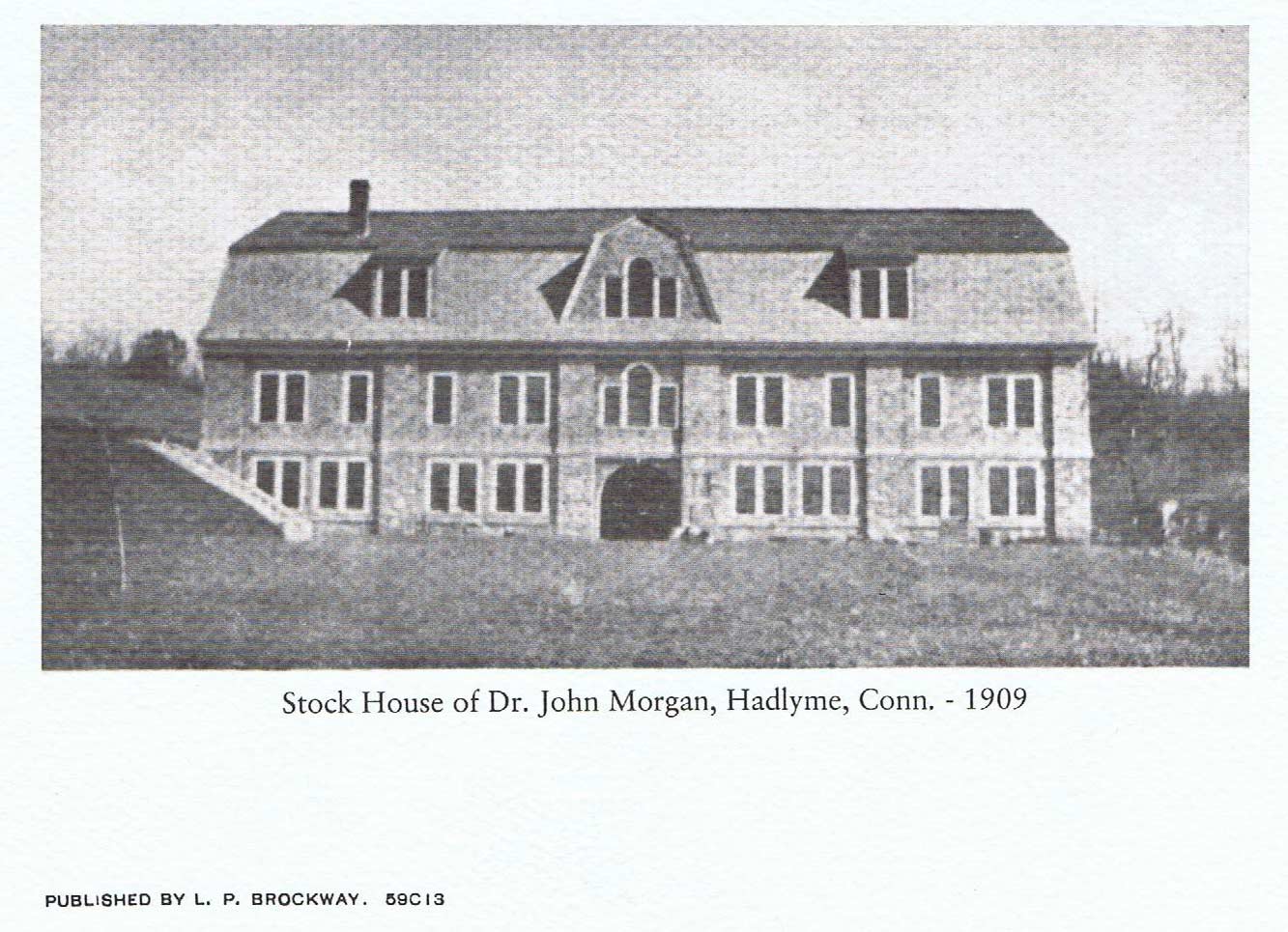

The architect of the grand stock barn remains unknown. Local tradition attributes the gambrel-roofed structure with its distinctive dormers and Palladian windows to legendary New York architect Stanford White (1853-1906), partner in the renowned firm of McKim, Mead & White. But despite some similarities to Stanford White’s designs, the shingle-style barn was almost certainly the work of a different architect. White, who was murdered in 1906 before the barn was completed, had stopped accepting residential projects in his later years. His collected papers include no documentation indicating a commission from the Boston eye specialist who constructed the expansive farm building in 1907 to house his dairy cows and prize race horses. [2]

Morgan’s Barn

Dr. John Morgan’s barn, Hadlyme, 1909

Dr. John Morgan (1845-1920), a house builder’s son who grew up in Hadlyme, was 62 when he added the elegant barn to his country estate. By then he had been raising trotting horses for thirty years. His interest in “runner-horses” developed in Middletown, a small industrializing city on the Connecticut River about midway between Hadlyme and Hartford, where he settled after completing a medical degree at Yale in 1869. [3]

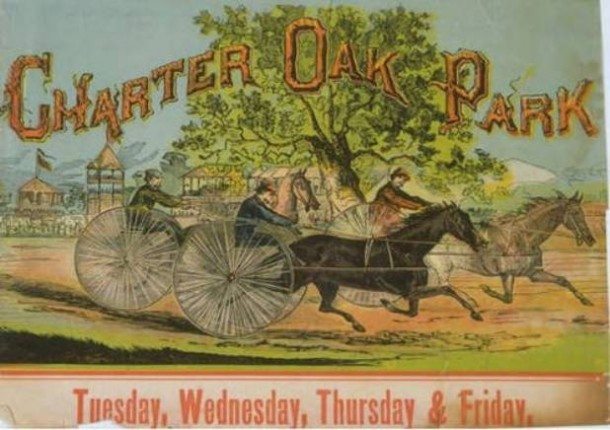

Advertisement for harness racing, Charter Oak Park, Hartford

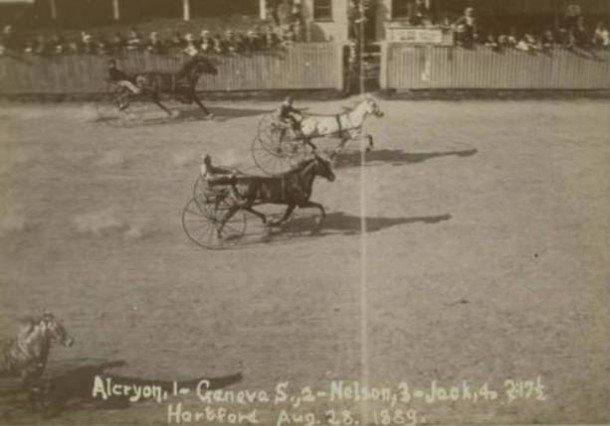

Harness racing, Charter Oak Park, 1889

Harness racing became a wildly popular sport after the Civil War. In 1873 a track opened at the Charter Oak Park in Hartford, and the U. S. Trotting Association soon listed Dr. John Morgan of Middletown among prominent owners and breeders. A columnist for The Hartford Courant reported in 1883 that: “Dr. John Morgan of Middletown sends Milton, a promising son of Smuggler, and other high-bred trotters to a sale in New York next Monday.” [4]

Dr. Morgan’s family, like that of his wife Antoinette Comstock Morgan (1844-1938), had deep roots in the Lyme-East Haddam area. The couple did not have children but began buying property in Hadlyme even before he established a medical practice on Huntington Avenue in Boston in 1895. There his professional reputation grew, his financial investments diversified, and in 1907 he became a director of the Exchange Trust Company, one of Boston’s newest banks. [5]

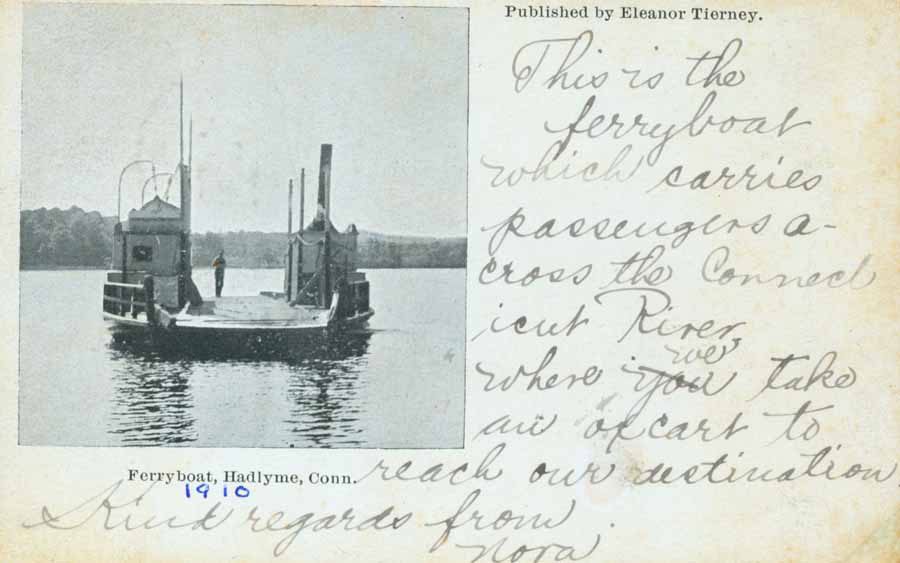

Hadlyme ferry, postcard sent by artist Nora Hamilton (1873-1945), 1910. Courtesy Werneth Noyes Collection

Dr. John Morgan’s home, later named “Grey Rocks.” The Hartford Courant, May 16, 1993

That same year his costly improvements to a century-old house not far from the Connecticut River ferry in Hadlyme became newsworthy. Dr. Morgan has “employed a large force of men on his place here and made it one of the most attractive homes in New London County,” The Hartford Courant’s local columnist reported. He “has expended several hundred dollars on the road leading to his magnificent residence” and is “building a barn with sufficient capacity to accommodate about a hundred head of cattle.” The Connecticut dairy commission inspected Morgan’s working barn the following year. Then overnight he became a millionaire. [6]

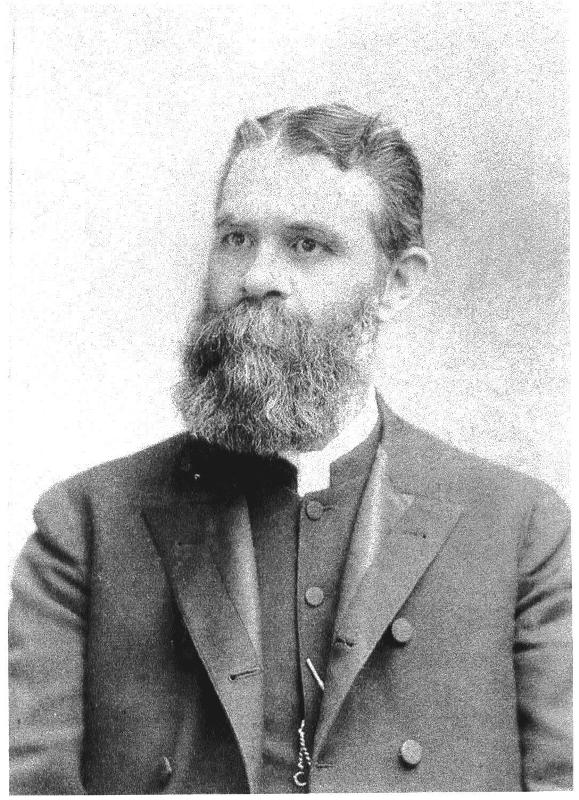

“It is just sheer luck that I should strike it so rich,” he said in 1909 after rich deposits of copper were discovered on a 2,200-acre Jamaica Island property he had bought on speculation. He had “no idea that anything would ever come of it,” his younger brother Dr. Edward Brainerd Morgan (1848-1925) told a reporter, “but some time ago heavy rains came and washed out vast amounts of copper.”

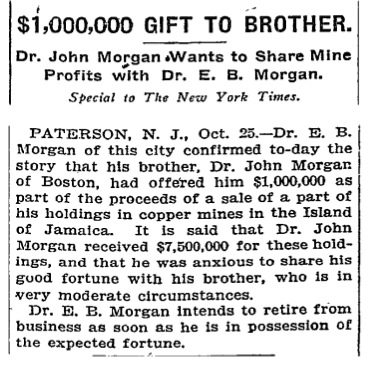

After the United States Smelting Company offered $7,500,000 for the copper mine property, Dr. Morgan’s decision to share his “unexpected fortune” with his younger brother, who had followed him to Yale and also become an eye specialist, drew national headlines. [7]

“The whole town of Paterson, N. J., was buzzing yesterday over the report that Dr. E. B. Morgan of that place is shortly to become the possessor of a million dollars through the generosity of his brother, Dr. John Morgan, the eye specialist of Boston,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. That generosity was already evident in Boston where he not only treated newspaper boys and other patients of limited means without charge but sometimes neglected to bill even his paying clients. Patients praised his extraordinary generosity, but some Boston physicians denounced his “unbridled philanthropy” as unprofessional, even “dangerous.” [8]

Dr. Edward Morgan, ca. 1910

“Doctor Makes Millions in Land Deal,” The New York Times, Oct. 26, 1909.

It may have been a comment by prominent New York Sun editor Charles A. Dana (1819-1897) that Dr. Morgan “knew more than anyone else about the human eye” which drew the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). Troubled by severe nearsightedness since childhood, the President in 1905 suffered a blow that blinded his left eye during a sparring match with a boxing partner in the basement of the White House. Determined to conceal from the public the serious impairment of his vision, the President consulted Dr. Morgan during a busy trip to Boston, supposedly for an adjustment to his glasses.

“The President came to me to have his glasses changed and have weaker ones substituted,” Dr. Morgan assured a reporter from The New York Times. “President Roosevelt’s eyes are wonderfully improving,” he alleged. Rumors of the President’s failing vision persisted, but the cover-up succeeded. It was not until 1918, a year before his death, that Roosevelt finally acknowledged the partial blindness that had resulted from his boxing injury. [9]

By then Dr. Morgan had retired to his Hadlyme home. “Two large auto trucks from Boston, Mass., were in town this week with Dr. John Morgan’s household goods,” The New London Day reported in 1915. “He also chartered a car to bring the heavy goods.” Two months later the newspaper noted that he “had four valuable horses shipped to his stock farm,” but his investments may already have been over-extended. When he readied a “tenement house” on one of his Hadlyme properties for occupancy in 1917, he perhaps needed income. [10]

Morgan’s barn, ca. 1978

Morgan’s barn, ca. 1978

Dr. Morgan died suddenly in Hadlyme in 1920 at age 75. His wealth had evaporated, and his estate inventory showed his thoroughbred trotters to be his largest asset. In addition to nine horses, the inventory itemized one cow, three heifers, office furniture, and a Hartford bank account with a meager balance of $161. It also included a long list of securities said to be “of doubtful value.” Once the horses were sold at auction and the creditors satisfied, a series of probate hearings concluded that “the estate of said deceased is insolvent.” [11]

An obituary in The Hartford Courant lamented the sudden passing of the famous eye specialist who had made his great knowledge and skill available to those unable to pay his fees. Praising him as “one of God’s noblemen,” the newspaper tribute offered no hint of financial decline. Antoinette Morgan, attempting to preserve her late husband’s reputation, specified in a will drafted in 1928 that she would donate his personal library as well as his portrait if the citizens of Hadlyme created a public library in his name. [12] The library was never built, and the location of Dr. Morgan’s portrait is not known,

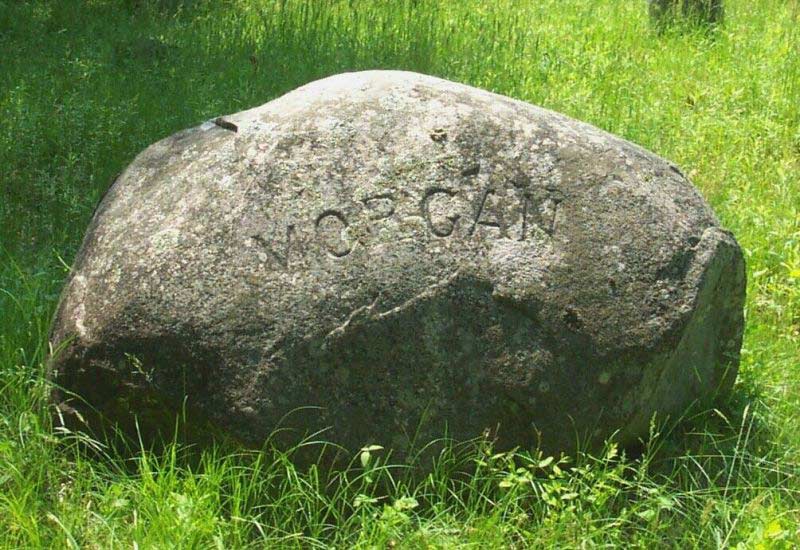

Lyme’s medical examiner reported the cause of his death as cerebral hemorrhage, but stories still swirl in Hadlyme about financial failure causing Dr. Morgan to end his life by throwing himself down his hay chute. Meanwhile his medical talent, his charitable acts, and his horse-breeding skills have been forgotten. Today a rough boulder in the Selden Cemetery close to his home commemorates the celebrated eye specialist’s passage through Lyme. Set far apart from the rows of silent grave markers and outsized like his stock barn, the huge rock bears only a single word MORGAN in large block letters.

Dr. Morgan’s Grave Marker, Selden Cemetery

In 1930, a decade after his death, Antoinette Morgan sold the monumental stock barn on a 10-acre parcel for “one and other dollars.” One of the boundary markers was “the Bull Lot, so called,” [13] from which Harry Holtzman later drew the name of his grand studio-home.

[1] Special thanks to Samuel White, Richard Lightfoot, Carolyn Bacdayan, Linda Winzer, Betsey Webster, and Amy Kurtz Lansing for their generous assistance. See Avenue (April 1981), p. 68; Steven Slosberg, “A New Meaning to Living in Barn,” The New London Day, November 30, 1995; Lyme Land Records (LLR) 60:469.

[2] The opinion of Samuel White, author with Elizabeth White of Stanford White, Architect (Rizzoli, 2008), who reviewed his great-grandfather’s plans and correspondence, is that the barn is “not by MM&W.” Email correspondence, October 9, 2013; see also “Historic Barns of Connecticut,” Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation

[3] Federal census, Lyme, 1860; The New England Jorurnal of Medicine, Vol. 80 (1869), p. 16; online biography of Dr. Edward B. Morgan

[4] See Connecticuthistory.org; Also see, Hartford Courant, March 12, 1883; John Hankins Wallace, Wallace’s Monthly, Vol. 9, p. 704.

[5] LLR 42:322, 43:266; Trust Companies, Vol. 5 (1907), p. 728

[6] Hartford Courant, October 26, 1907; Report of the Dairy and Foods Commissioner (winter 1908), p. 17

[7] Hartford Courant, October 26, 1909; The New York Times, October 26, 1909.

[8] “Doctor Makes Millions and Divides His Wealth with His Brother,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 26, 1909; also see Hartford Courant, November 3, 1920.

[9] “The Life of Theodore Roosevelt,” National Park Service online biography; “Roosevelt’s Day,” Boston Daily Globe, June 28, 1905; “Oculist for Roosevelt,” The New York Times, June 21, 1905; “President’s Eyes Improve,” The New York Times, July 7, 1905.

[10] The New London Day, November 20, 1915, and November 10, 1917.

[11] Lyme Probate Records (LPR), 5:130, 5:133.

[12] Hartford Courant, September 2, 1920; LPR, 6:336-7.

[13] LLR, 49:163.