By Carolyn Wakeman

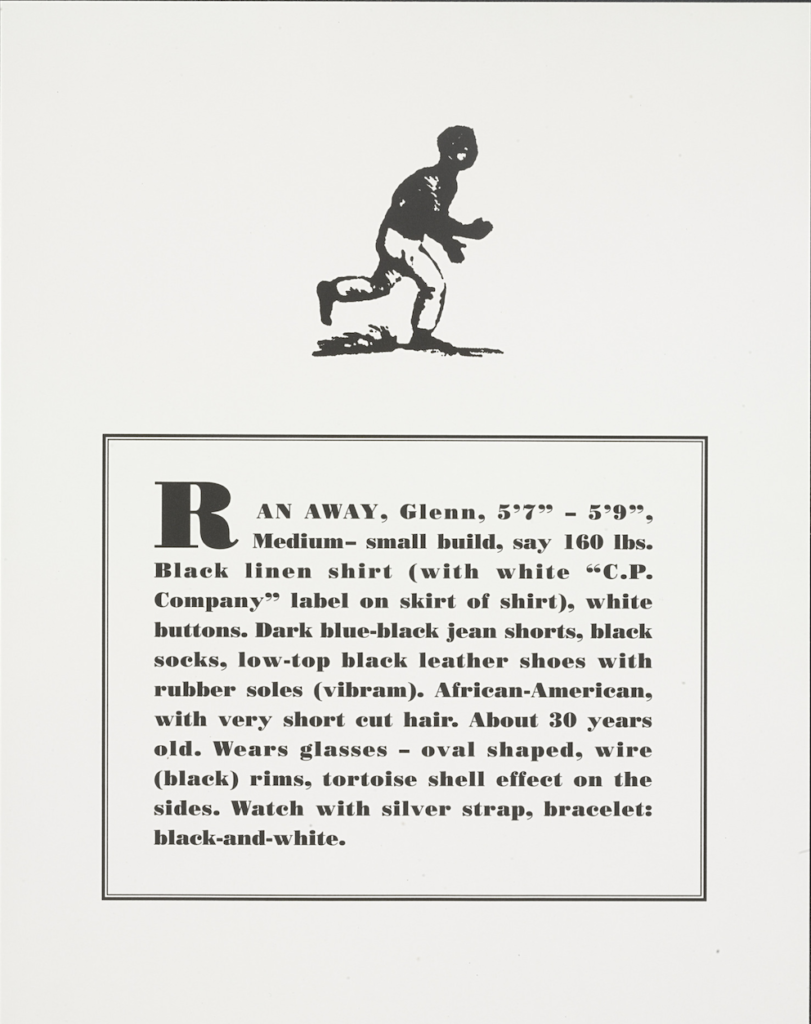

Featured Image: Glenn Ligon (b. 1960), Untitled from Runaways, 1993. Photolithograph. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase. 2022.4.1-10

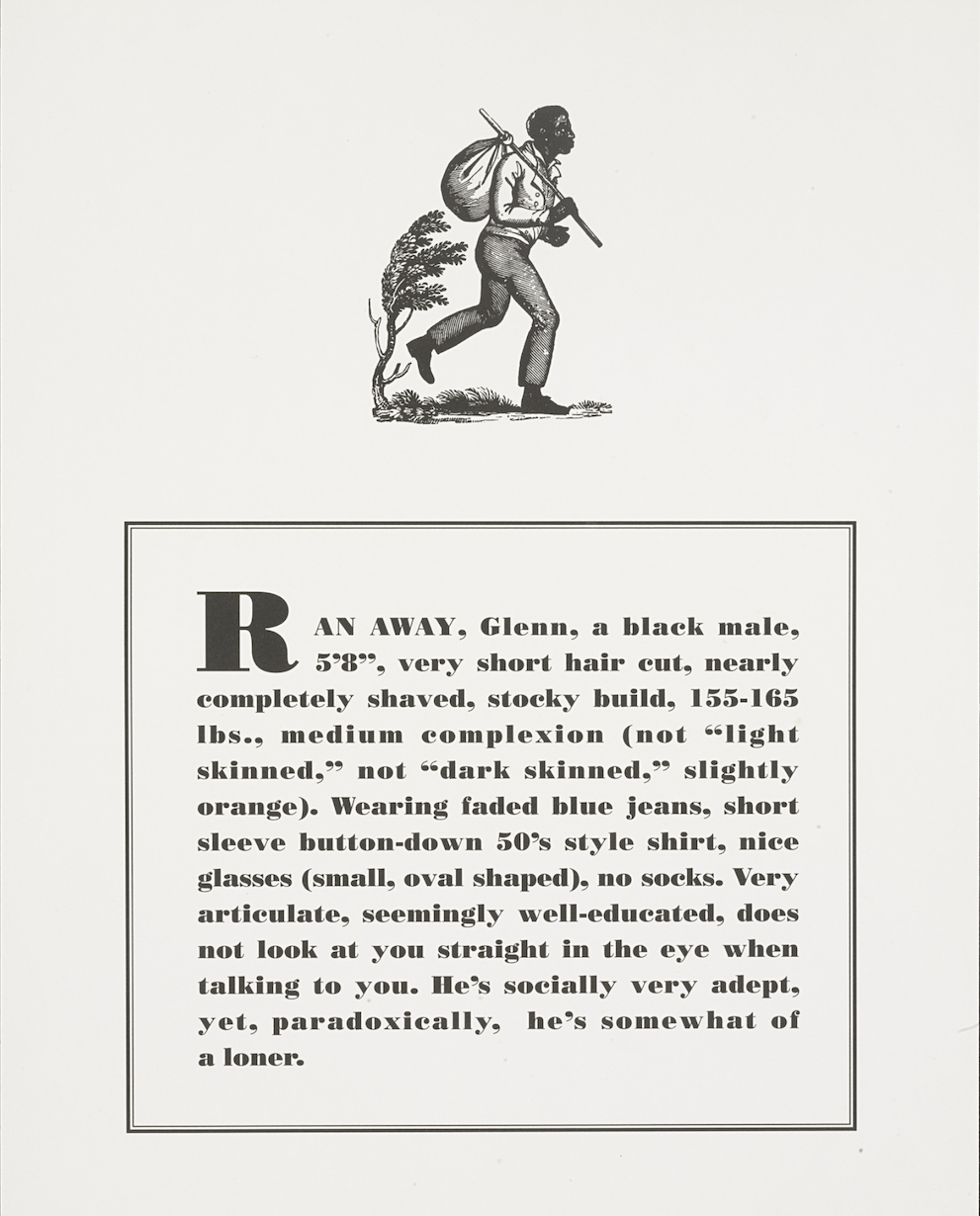

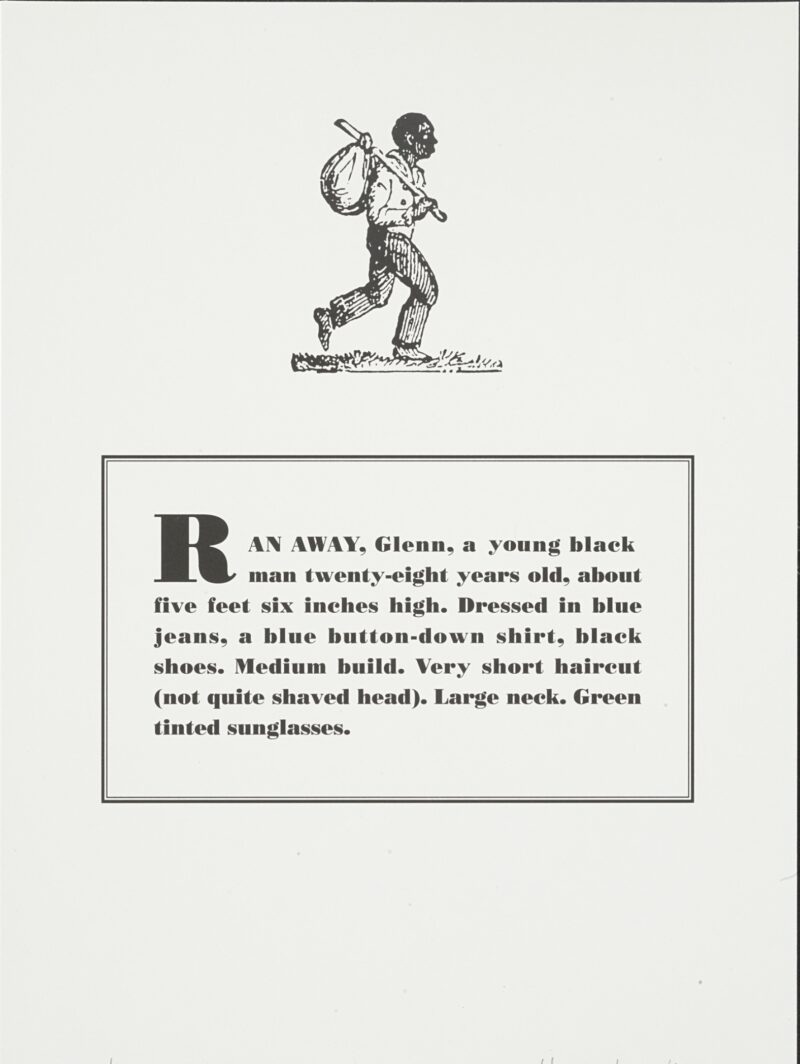

The Florence Griswold Museum’s exhibition Dreams & Memories, on view from October 1, 2022, through May 14, 2023, offers riveting juxtapositions of traditional and modernist works from its collection to shed significant new light on ways of viewing the remembered past. Featured in the exhibition are ten recently acquired lithographs by New York-based artist Glenn Ligon, a graduate of Connecticut’s Wesleyan University. In this 1993 print portfolio titled Runaways, Ligon repurposes 18th and 19th-century “wanted” posters circulated by slave owners attempting to retrieve lost property.

The reimagined posters incorporate stock silhouettes of escaped slaves and abolitionist leaders. They also preserve the conventional format and typeface of runaway advertisements widely publicized in both North and South, but the accompanying text offers a startling departure. Rather than including descriptive details about historical runaways, Ligon’s posters offer details about his own appearance, elicited from friends and colleagues. The substitution of the artist’s features, clothing, and gait for those of individuals who fled from bondage creates a witty but sardonic self-portrait. While the updated runaway ads may seem initially to offer a lighthearted collision of present and past, humor fades as the implications of the text blocks accumulate. By disrupting the comfortably distanced stance of viewers, Ligon engages them with the continuing power of stereotypes and assumptions from the slave-owning era.

Glenn Ligon (b. 1960), Untitled from Runaways , 1993. Photolithograph. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase. 2022.4.1-10

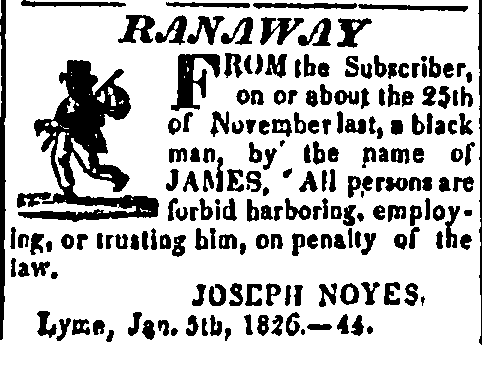

The Runaways portfolio acquires added urgency when viewed alongside 21 advertisements published in the Connecticut Gazette describing slaves who fled from Lyme owners between 1764 and 1826. One notice, dated January 26, 1826, calls for the return of “James, Black man,” who ran away from Joseph Noyes, Jr., the previous November. “All persons are forbid harboring, employing, or trusting him, on penalty of the law,” the advertisement warns. Noyes, then 26, had grown up alongside more than two dozen enslaved Blacks who served in the households of his father, mother, grandparents, and cousins. The stock image of a fleeing slave carrying a knapsack, wearing a jacket, trousers, and hat, accompanies the notice. “James, Black man” is the last person known to have been held in bondage in Lyme.

Advertisement for James, The Connecticut Gazette, January 25, 1826, page 3

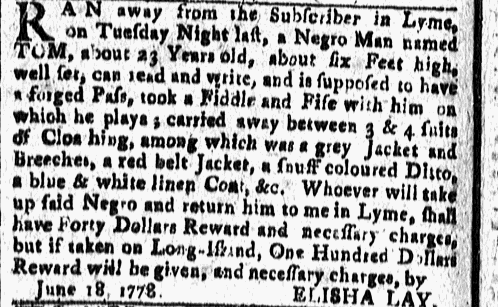

Owners seeking the return of their fugitive slaves provided vivid details about the circumstances of those they considered property. Boston, age about 28, who ran away from Ezra Selden in August 1761, “hath some Scars of the Small Pox about his Nose.” A Negro man named Tom, age about 23, who ran away from Elisha Lay in June 1778, taking with him a fiddle and a fife, could read and write. The mulatto Caesar who ran away from John McCurdy in 1784 had been to sea, had resided some time on Long Island, and was a frequent runaway. The Negro boy slave Frank who ran away from Joshua Powers in 1798 had the “middle part of his right ear missing by the kick of a horse when a child.” A Negro boy, age about 21, who “calls himself Robin” and ran away from Jasper Peck in July 1800, was “very black,” had “thick lips,” had been to sea, and was “very ignorant, cannot count the number ten.”

Advertisement for Tom, The Connecticut Gazette, July 3, 1778, page 4

Newspaper notices also provided precise details about the clothing worn by those locally enslaved, who frequently layered their garments when they fled, perhaps for later use as currency. Tom, age about 23, “carried away between 3 & 4 suits of Clos” when he ran away from Elisha Lay in 1778. Boston left wearing a “Check Woolen Shirt, a short stone-grey plain Cloth Dublit or Jacket without any Sleves or Buttons, a pair of short Trowsers, no Hatt, Cap, Stockings or Shoes.” Sambo, who ran away from John Mumford in April 1770 and was “about five Feet and an half high,” had on “a lightish colour’d Kersey Jacket and Breeches, Striped Flannel under Vest, white Flannel Shirt, and dark grey Stockings.”

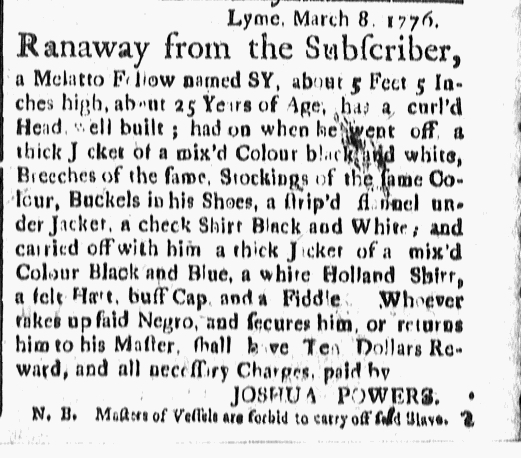

Tim, a “Negro fellow” who ran away from Elisha Miller in May 1770 and was about 28, had on when he fled a “white Felt Hat, grey home-made Kersey Great-Coat, one blue Serge Jacket, and one striped Kersey Ditto, two striped Waistcoats, one striped flannel Shirt, one check’d Linen Ditto, strip’d Woollen Trowsers, snuff-colour’d Breeches, two Pair stockings, one pair Shoes, one Ditto Pumps.” Sy, a “Molatto Fellow,” age about 25, had a “curl’d head” and was “well built.” When fleeing from Joshua Powers in March 1776, he had on a “thick Jacket of a mix’d Colour black and white, Breeches of the same, Stockings of the same Colour, Buckels in his Shoes, a strip’d flannel under Jacket, a check Shirt Black and White, and carried off with him a thick Jacket of a mix’d Colour Black and Blue, a white Holland Shirt, a felt Hatt, buff Cap.” Sy also carried off a fiddle.

Advertisement for Sy, The Connecticut Gazette, March 22, 1776, page 3

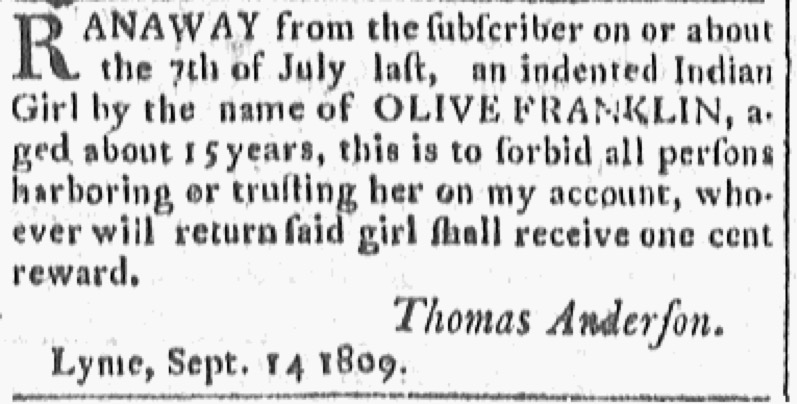

Rewards that property owners offered for Lyme runaways show wide discrepancies in the values assigned to persons enslaved. Those with the lowest value were indentured Native American youths and older African-descended slaves. Anyone who returned the Indian girl Olive Franklin, age 15, to John Anderson in 1809 would receive one cent. Return of the Indian boy Samuel Weaukeat, age 18, to Dr. John Noyes in 1805 would bring fifty cents. Hurlbut Swan in 1801 offered one dollar for the return of the Indian boy Phillip Pharaoh. Also low in value, with rewards of six cents each, were the Negro slaves Cuff, age 46, and Pomp, age 40. Pomp, enslaved by Joseph Noyes, Sr. was “blind of one eye, and sees imperfectly with the other.” The return of Boston, Sambo, Tim, Sy, Tom, Caesar, Sawn, and Robin, would bring higher rewards, ranging from 20 shillings to ten dollars. Frank’s apprehension would bring fifty dollars; Tom’s return would bring twice that amount.

Advertisement for Olive Franklin, The Connecticut Gazette, September 27, 1809, page 3

Enoch Lord, who had inherited extensive acreage along the Connecticut River from his slave-owning parents, offered the highest reward publicized in Connecticut Gazette advertisements. Lord would give “Two Hundred Dollars Reward, and necessary Charges,” for the return of the ”Negro man Caesar,” who ran away in March 1780. The advertisement notes that Caesar played on the violin, spoke pretty good English, was “much inclined to Liquor,” and took with him a “large Bundle of Cloathes, about one Thousand Dollars and a Violin.” Lord’s cousin John Lord left open the amount he would give to retrieve his “negro man servant named Josephus,” who ran away in December 1784. Josephus was about 30 years old, about 5 feet 10 inches high, and “a tall slim fellow.” One of his eyes “had a blemish on it,” and when he “went away,” he wore a light brown coat, a brown fustian jacket, double breasted, a pair of light brown cloth breaches, a pair of white ticking [ditto], one pair of striped trowsers, one pair of white cotton stockings, one pair of mixt yarn [ditto] and other clothing.” John Lord’s advertisement announced that, “Whoever will take up said fellow and return him to me” would receive a “handsome reward,” with “necessary charges paid.”

How many Lyme runaways were apprehended has not been discovered, but the Connecticut Gazette provides occasional clues about their subsequent circumstances. One advertisement tells us that Caesar was a “frequent runaway,” while two others show that an enslaved person ran away from different owners. When Jasper Peck advertised in August 1800 for a Negro Boy who “calls himself Robin Peck,” Robin was “about 21 years old, very black, thick lips, about 5 feet 3 inches high.” He had “been to sea” and had a “scar on the back part of his head under his wool,” and he fled wearing a “home made short serge Coat, swansdown under Jacket, tow cloth Shirt and Trousers.” When Charles and Shubel Smith advertised for Robin’s return three years later in June 1803, he was about 24. The Smiths described Robin as “very black, thick set about the shoulders, large mouth and white teeth, broad face, small feet and legs” and noted that he “travels not handsome, by reason of his feet having been frozen.” They also noted that he had been “two voyages to sea” and was “very ignorant, being unable to count the number of twenty.” The second time Robin “went away,” he wore a “blue sailor jacket and trowsers, checked shirt, striped jacket and black hat” and “carried with him, one pair brown or dark olive colored corduroy pantaloons, 1 striped cotton shirt, one white linen [ditto], 1 pair tow cloth trowsers, one long, white cravat, and sundry other clothing.”

Few other sources provide details about local runaways. The Lyme treasurer’s report tells us that in 1815, six years after Olive Franklin ran away, the town assumed her support and paid for the burial of her child. A gravestone in Duck River Cemetery states that Pomp, for whom Joseph Noyes, Sr. had advertised in 1816, died six years later, presumably in Lyme. The gravestone, likely placed by a Noyes descendant, tells us that Pomp Freeman, son of Prince & Jenny, died Aug. 9, 1822, at age 46. No indication that Pomp was emancipated has been found, and the surname “Freeman” was likely assigned posthumously.

Gravestones in Duck River Cemetery commemorating four persons enslaved by the Noyes family, including Pomp Freeman

By calling back into view those who attempted to escape from bondage in Lyme, Glenn Ligon’s Runaways portfolio reminds visitors to the Florence Griswold Museum of a forgotten era. As Revolution loomed in 1774, a census count showed 6,464 slaves in Connecticut, more than in any other New England colony, with 2,036 slaves in New London County, the highest number of any county in New England. The 1774 census in Lyme, taken two years before Pomp Freeman was born, showed a population of 3,860 whites and 228 “Total Blacks,” of whom 124 were Negroes and 104 Indians. That same year the Connecticut colony passed a law to halt the importation of slaves, whether Indian, negro or mulatto, under penalty of a 200-pound fine. The law noted that “the increase of slaves in this Colony is inurious [injurious] to the poor and inconvenient.”

A century later in a laudatory profile of the town published in 1876 in the centennial issue of Harper’s magazine, historian Martha J. Lamb noted that, “In the palmy days before the Revolution . . . all the consequential families in Lyme owned negro slaves.” Social attitudes shifted in the early 1900s, and Black laborers imported from Barbados and other colonies in the British Atlantic were no longer viewed as markers of northern wealth and status. Black and native servants in Lyme had by then been replaced by Irish immigrants fleeing famine, and the African-descended families who had contributed importantly to the town’s economic growth slipped from memory. For the metropolitan artists who settled after 1900 in the town renamed Old Lyme, the scenic village seemed to be a place, in the words of Lyme Art Colony founder Henry Ward Ranger, “only waiting to be painted.” Its pastoral landscape created the charming impression of an American Giverny.

Edmund Greacen (1876–1949), The Old Garden, ca. 1912. Oil on canvas, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Edmund Greacen, Jr., 1974.1

For seasonal visitors poverty, famine, and the war in Europe seemed remote from the sun-drenched fields, laurel-covered riverbanks, nostalgic flower gardens, and historic homes. They failed to notice the local almshouse or the young men leaving their homes and families to fight on the battlefields of France. The journalists who arrived from New York or Boston to review the artists’ summer exhibitions praised their luminous portrayals of rural serenity, and a New York Times reporter in 1928 expressed the prevailing view that, “In this dreamy and delicious little place nothing changes.” Even more invisible to Old Lyme’s visitors was the town’s history of enslavement. In the North slavery had increasingly become known as a southern institution, and the artists who enjoyed convivial lunches on the side porch of what is today the Florence Griswold Museum had no idea that four generations of enslaved persons had served on the estate that their charming hostess inherited.

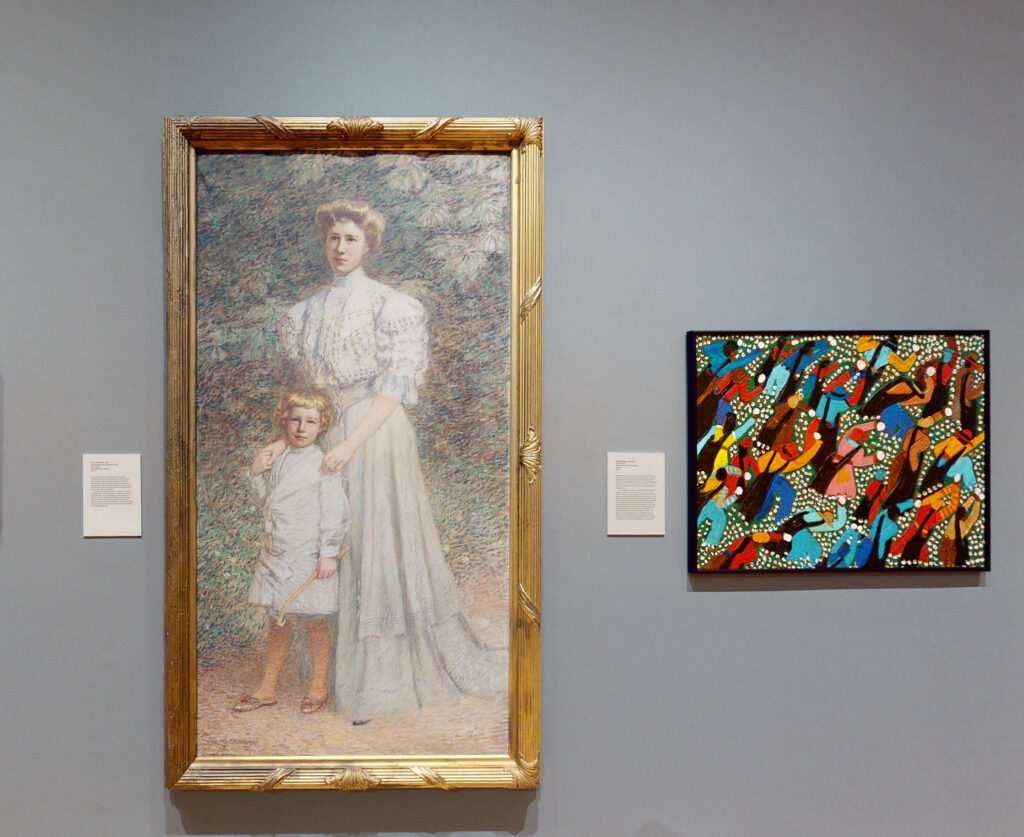

Gallery view of Dreams & Memories featuring a portrait by Walter Griffin and Winfred Rembert’s Cotton Pickers

By displaying Glenn Ligon’s boldly imagined Runaways lithograph series, and other recent works like Winfred Rembert’s Cotton Pickers, alongside more traditional portraits and landscapes, the Dreams & Memories exhibition interrupts a longstanding gap in social memory. In the ten different iterations of wanted ads that position Ligon himself as an escaped slave, the distance between today’s viewing audience and the readers of runaway notices in the Connecticut Gazette two centuries ago collapses. Ligon’s unsettling invitation for viewers to imagine themselves, and not just the artist, as fugitives during the slave-owning era recalls with jarring urgency the circumstances of Robin, Tom, Sy, Olive Franklin, and others in historic Lyme who dared to undertake far more dangerous and consequential acts of resistance.

Glenn Ligon (b. 1960), Untitled from Runaways , 1993. Photolithograph. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase. 2022.4.1-10