By Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Image: James Prosek, Old Lyme by Land and Sea, 2019, Acrylic paint on sheet rock. Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York. Photograph by Paul Mutino

As the balance between humans and the planet they inhabit becomes ever more precarious, the Florence Griswold Museum’s dynamic summer 2019 exhibition Fragile Earth: The Naturalist Impulse in Contemporary Art probes traditional ways of viewing and engaging with the natural landscape. James Prosek’s panoramic black and white wall mural Old Lyme by Land and Sea (2019), created for the exhibition, dominates the first gallery. Within that space the artist positioned Striped Bass (2017), the study of a common local fish, recently acquired for the museum’s permanent collection. Above and below the rainbow-hued still life, graceful black shapes of birds, sea grasses, and marine life found at the mouth of the Connecticut River locate the striped bass, a catch prized by sport and commercial fishermen, in a larger ecosystem.

James Prosek, Striped Bass, 2017. Oil and acrylic on panel. Florence Griswold Museum, Purchase.

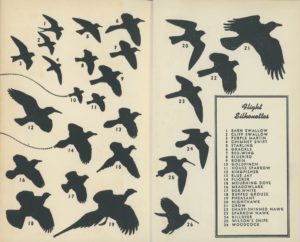

Old Lyme by Land and Sea requires shifting viewpoints. Observers step back to contemplate its expansiveness, then draw close to admire the shimmering details of the life-sized striped bass. Those alternating perspectives engage them in the artist’s vision. While Prosek celebrates the distinguishing characteristics of an individual specimen, he simultaneously challenges the urge to name, classify, own, and display, trophy-like, nature’s variety. The surrounding numbered silhouettes of birds perched and in flight recall similar black forms arrayed on the endpapers of ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson’s best-selling A Field Guide to the Birds, first published in 1934. Peterson (1908–1996) provided a key that invited readers to identify each silhouetted bird, but Prosek withholds a comparable name list. The silhouettes in his mural convey not what differentiates individual species but what connects them in a habitat that viewers also share.

Roger Tory Peterson, “Flight Silhouettes,” A Field Guide to the Birds: Giving Field Marks of all Species Found East of the Rockies (Boston, 1963)

Prosek invites reflection on the field methods of earlier naturalists in Old Lyme. Before Roger Tory Peterson encouraged amateurs and professionals alike to distinguish birds in their native setting, identification often resulted from shooting a specimen to confirm its location and characteristics. Ornithologists in the past, Peterson wrote in the Field Guide’s Preface, “seldom accepted a sight record unless it was made along the barrel of a shotgun.”[1] Those interested in discovering the habits of birds, he urged, should rely instead on binoculars and “trust their eyes.” In 1952 Peterson purchased a house on Neck Road in Old Lyme called “The Cedars” and there continued to write, illustrate, and promote environmental awareness.[2]

Birding as Sport

More than half a century before the publication of Peterson’s Field Guide, Edward Augustus Samuels’ definitive guidebook The Birds of New England (1870) included tips for hunters along with comprehensive descriptions for ornithologists and collectors. After sketching out the migration patterns of the golden plover, Samuels (1836–1908) detailed the successful methods of sportsmen. “When the flights are conducted during a storm,” he advised, “the birds fly low; and the gunners, concealed in pits dug in the earth in the pastures and hills over which the flocks pass, with decoys made to imitate the birds, placed within gunshot of their hiding-places, decoy the passing flocks down within reach of their fowling-pieces, by imitating their peculiar whistle, and kill great numbers of them.” In spring, Samuels noted, the golden plover “is thin in flesh, but its plumage is perfect; and it is more desirable for cabinet preservation than in the fall…when these birds are most actively pursued by sportsmen.” He added that he “had known two sportsmen to bag sixty dozen in two days’ shooting.”[3]

Edward Augustus Samuels, The Birds of New England and Adjacent States (Boston: Noyes, Holmes, and company, 1875.)

Forty years later John Hall Sage (1847–1925), the long-serving secretary of the American Ornithologists’ Union, reported in The Birds of Connecticut (1913) that the golden plover had been “plentiful at Lyme Sept. 1, 1858, 104 being shot on that day by John Grumley.” But Sage warned that sightings of the golden plover had declined sharply. Once “common during migrations” in Connecticut, it had recently become “a rare fall migrant.” Sage specified that unlike hunters, collectors, did no harm. “No one need fear that collecting would prevent a species from establishing itself in our state,” he wrote, unless “it was destroyed for sport or millinery.” The collecting of eggs for scientific purposes, even by boys, he asserted, “can never appreciably reduce their numbers, as long as they are protected from too much slaughter in the name of sport.”[4] Sage himself, a banker by profession, was “always a collector,” his obituary notes. He never lost his “boyish delight in the acquisition of some rare specimen,” but he also had “no patience with those who did not believe in shooting birds for scientific purposes.” He bequeathed his “remarkably complete” series of “beautifully prepared bird skins” to the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, where he served as the honorary curator of ornithology.[5]

The Collector’s Pursuit

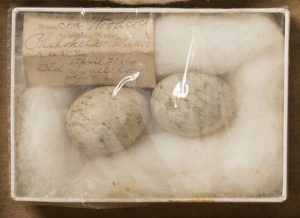

The study of birds’ eggs, called oology, became a popular hobby in the late 19th century, and Hadlyme grocer and ornithologist Arthur Brockway (1875–1946) assembled a large collection of specimens. Brockway was sixteen in April 1891 when he gathered two American woodcock eggs later purchased by, or perhaps traded with, New York landscape artist Willard Metcalf (1858–1925), also an avid collector. “Their ground-color is usually a rich creamy-drab,” Samuels’ field guide noted, “sometimes with a slight olive tint, and they are marked, more or less thickly, with coarse and fine splots and blotches of two shades of brown, and obscure shades of lilac.”[6] Today the woodcock eggs Brockway collected more than a century ago can be viewed in Willard Metcalf’s 28-drawer wooden specimen cabinet, featured in the Fragile Earth exhibition.

American Woodcock eggs gathered in Old Lyme by Arthur Brockway. From Naturalist Collection Chest, ca. 1885-1925. Mahogany wood drawer, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Henriette A. Metcalf

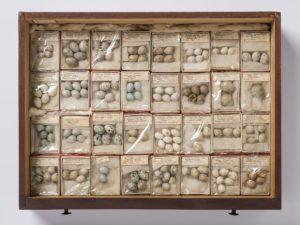

Drawer 1B, containing bird eggs collected by Willard L. Metcalf in Giverny and Grez-sur-Loing from his Naturalist Collection Chest, ca. 1885-1925. Mahogany wood drawer, Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of Mrs. Henriette A. Metcalf

Metcalf spent three consecutive summers, beginning in 1905, at Florence Griswold’s boarding house, where he completed several of the paintings considered his most important achievements, among them a shimmering view of her home in moonlight titled May Night (1906). Metcalf kept a list of birds sighted during his months with the art colony and continued to build his specimen collection. His cabinet displays eggs of the blue winged warbler, the wood peewee, and the green heron as well as nests of the redstart, the yellow-throated chat, and the prairie warbler, all collected in Old Lyme.[7] Six months before painting May Night, which Florence Griswold praised as “the best thing you’ve ever done,” Metcalf posted a notice in The Oologist offering cash for copies of The Osprey, an illustrated magazine of popular ornithology.[8]

Willard L. Metcalf, May Night, 1906. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund)

Metcalf did not return to Old Lyme in the summer of 1908 when he published a field note in The Oologist reporting his observation in Cannon [likely Canaan], Connecticut, “on the lower drooping branch of an apple tree about five feet from the ground, [of] a nest of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird containing two eggs which were hatched on June 8th.” Metcalf watched the nest at daily intervals, he wrote, until June 30th “when the youngsters were about ready to sever their connection with the nest.” Called away for a week, he returned on July 6th and again visited the nest, intending to collect it. After watching the female fly away, he found the nest contained one egg and the next day a second egg. When he left on July 13th, the female was again sitting on the nest, which he cited as evidence that hummingbirds nest later than noted by other ornithologists and rear “two broods, when undisturbed; though perhaps this is unusual.”[9]

When Clark Voorhees (1871–1933) joined the artists at Florence Griswold’s boarding house in the summer of 1901, four years before Metcalf’s arrival, he also brought a naturalist’s vision to landscape painting. His keen interest in collecting overlapped with a love of hunting for sport. “While collecting in a piece of low, swampy woods at Rye, Westchester Co., N.Y. on Aug. 31, 1888,” Voorhees reported in a field note published in The Auk, “I shot a Warbler, which…proved to be a Lawrence’s Warbler (Helminthophila lawrencei). This bird, an adult male, is in excellent plumage.”[10] Four years later in 1892, he published a note on the “Occurrence and Breeding of the Kentucky Warbler in Connecticut” that described hearing an unfamiliar bird note near a path in Greenwich. “Not having a gun near at hand,” Voorhees watched her for some time, then returned at dusk and “secured” the male.

The Auk: A Quarterly Journal of Ornithology (January, 1897)

Despite Sage’s acceptance, the reliance on a shotgun for collecting drew criticism after the turn of the 20th century. In a “Special Article” for Science magazine in 1905, William E. D. Scott (1852–1910), an ornithologist at the Worthington Society for the Investigation of Bird Life in Pennsylvania, noted Voorhees’ publications in The Auk. A field note in July 1894, reporting that he “took an adult female” which proved to be a Lawrence warbler, contributed to Scott’s call for restraint. “It behooves every good field naturalist not to add more specimens of these birds to our collections, but to carefully observe them as they exist, alive,” he wrote.[11] After completing a master’s degree in chemistry at Columbia in June 1893, Voorhees had already enrolled at the Art Students League in New York to begin his formal study of painting, and he published no subsequent field notes. Although it was duck hunting that initially drew him to Old Lyme in the summer of 1896,[12] the company of other artists with a shared passion for landscape painting led him to buy a house in 1905 along the Connecticut River on Neck Road, not far north of the property Roger Tory Peterson would purchase half a century later.

Arthur Brockway’s Specimens

Brockway’s boyhood pastime collecting birds’ eggs led to his becoming a seasoned field naturalist. His earliest published note described his first sighting of a Carolina wren in Connecticut in December 1897. Brockway, then 22, had recently returned from a sailing trip to the islands off the South Carolina coast and up the St. John’s River in Florida with Willis W. Worthington (1860–1939), an ornithologist from nearby Shelter Island. Worthington, who referred to his companion as a “boat-building expert from Lyme, Connecticut,” noted in his journal that they collected birds and eggs throughout their trip.[13]

Brockway had already posted in 1893, at age eighteen, a notice in The Oologist offering to exchange literary works, perhaps his school books, among them Ivanhoe and David Copperfield, for books on ornithology.[14] After returning from South Carolina in 1897, he offered to exchange “rare sets of eggs” for the latest edition of Samuel’s Birds of New England. The next year he published a second field note in The Auk reporting the rare sighting of a turkey vulture. “While out driving in Old Lyme, Conn, August 31, I was much surprised to note a Turkey Buzzard (Catartes anra) in Company with a Red-shouldered Hawk, flying around a small patch of woods,” Brockway wrote. “This is the first one I have seen so far north as Connecticut.” The next year he described the odd nesting of a Maryland Yellow-throat in a shoe left outside the back door of a house on Old Lyme’s main street, adding that “the shoes, nest, and eggs are in my collection.”[15]

The Oölogist, Volume XXVI, No. 12, December 15, 1909.

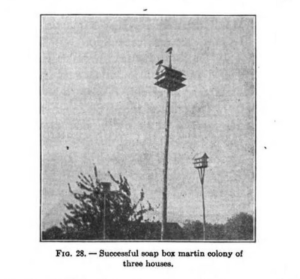

A decade later in a pair of advertisements posted in The Oologist in 1909, Brockway sought new binoculars as well as books to expand his library. He offered to exchange Indian relics, [bird] skins and eggs for “a pair of Marine Field Glasses: must be very clear and strong magnification.” A second listing provided additional details: “Books of birds of northeast and eastern North America, pair of best opera glasses and taxidermists instruments: have for exchange fresh [bird] skins, Horned Owl, R.S. Hawk, fine specimens. Arrow points, axes, pestles, etc. Sharks teeth from South Carolina river bottoms.” Meanwhile a faded photograph indicates that Brockway by 1915 had used grocery cartons to construct a series of bird houses that attracted a large colony of martins.[16]

Arthur Brockway’s martin houses. Sixty Third Annual Report of the Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture, pg. 221

Arthur Brockway and Charles Morley near Baptist Church, ca. 1900. Lyme Historical Society Archive at the Florence Griswold Museum

Brockway’s ongoing field notes report observations of the small blue heron, the catbird, the Canada warbler, and black ducks growing tame. In 1918 he described in The Auk the unusual presence in Hadlyme of a flight of great horned owls, which had been “fast nearing extinction in Connecticut.” The game keeper of a local pheasant farm, he reported, trapped and killed during that unusually cold winter 91 great horned owls, 25 barred owls, 15 screech owls, 9 long-eared owls, and 84 goshawks.[17] Brockway opted for the camera over the shotgun, as attested to in an item in The Day, which informed readers “Arthur W. Brockway was in Amston Thursday, photographing wild ducks and other birds at the Audubon society experiment station.”[18] Brockway’s last field note for The Auk, written at age 75, indicated that the shotgun remained in common use for identification. In January 1945 he reported that a dovekie, a small auk that breeds in Alaska, had been shot during a severe wind and rain storm on a creek at Lord’s Cove in Lyme and brought to him. “It furnishes the only record, since the big flight of November 19, 1932, which extended from Massachusetts to southern Florida,” he wrote, “when thousands of these little auks perished.”[19] A later edition of Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide, echoing Brockway’s field note, reports that the dovekie was “occasionally driven ashore and even inland by prolonged ocean gales.”[20]

Roger Tory Peterson, Dovekie, summer and winter views, A Field Guide to the Birds (1964)

James Prosek, painting at Florence Griswold’s estate more than a century after Willard Metcalf and Clark Voorhees joined the art colony in Old Lyme, applauds the achievement of earlier naturalists but offers a different and more urgent vision. His Striped Bass delights in the particularity of a collected specimen’s identifying features, and the mural that contains it embraces Peterson’s reliance on the observer’s eye. But Prosek celebrates the beauty and diversity of the natural setting as a way of alerting viewers to their own role and responsibility, not only to appreciate but also to protect and preserve the ecosystem that they also inhabit.

Endnotes:

[1] Cited in Thomas C. Gannon, “‘A Most Absorbing Game’: Peterson’s Field Guide and the New World Bird as Colonized Other,” The Ampersand 11 (2002); https://tgannon.incolor.com/petguide.html

[2] Douglas Carlson, Roger Tory Peterson: A Biography (Austin, 2007), pp. 150-151; Christine Woodside, “Where Bird Guides Were Born, Soon a Refuge?” The New York Times (February 3, 2002).

[3] Edward Augustus Samuels, pp. 414-415.

[4] John Hall Sage, pp. 65, 11. Robert Craig, “Riparian Habitats,” in Great Day Trips to Connecticut’s Critical Habitats (2004), p. 116. Federal census records note that John Grumley (1823–1903), who lived in Saybrook, worked as a pilot.

[5] Witmer Stone, “In Memoriam—John Hall Sage,” The Auk (1926), 43:6-7.

[6] Samuels, p. 434.

[7] Amy Ellis, “Natural Wonders,” in Bruce W. Chambers, May Night: Willard Metcalf in Old Lyme (Old Lyme, 2005), p. 86.

[8] W. L. Metcalf, The Oologist (January 1906), 23:1.

[9] Willard L. Metcalf, “Ruby Throated Hummingbird: Two Broods from One Nest,” The Oologist (October 1909) 26:163.

[10] Clark G. Voorhees, “A Third Specimen of Lawrence’s Warbler,” The Auk (1888), p. 427.

[11] William E. D. Scott, “On the Probable Origin of Several Birds,” Science (September 1, 1905), 22: 279-280; cites Voorhees, The Auk 5:427 (1888), and 11:259-260 (1894).

[12] Marshall N. Price, The Light Lies Softly: The Impressionist Art of Clark Greenwood Voorhees (New York, 2010), p. 9.

[13] Arthur W. Brockway, “Carolina Wren at Lyme, Conn, in December,” The Auk (1898), 3: 274; David W. Johnson, “Explorations and Bird Collections of Willis. W. Worthington in Florida,” Southeastern Naturalist 12:4 (2013), p. 743.

[14] The Oologist (1893) 10:162.

[15] Arthur W. Brockway, “The Turkey Vulture in Connecticut,” The Auk (1898), 15:53; “Odd Nesting of Maryland Yellow-throat,” The Auk (1899), 360-361.

[16] The Oologist (December 15, 1909), 26:205.

[17] Sixty-third Annual Report of the Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture Yearbook, Part II (Boston, 1916), p. 212; Arthur W. Brockway, “Large Flight of Great Horned Owls and Goshawks at Hadlyme, Connecticut, The Auk (1918), 35:351-352.

[18] “Hadlyme, Items of Interest,” The Day, September 22, 1917, p. 9

[19] Arthur W. Brockway, “A Dovekie in Connecticut,” The Auk (1945) 3:460.

[20] Roger Tory Peterson, A Field Guide to the Birds (Cambridge, MA, 1963), p. 126.