by Carolyn Wakeman

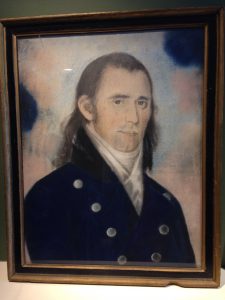

Featured image (above): James Martin (English, active in America 1794–1820), Judge William Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Museum Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

The Florence Griswold Museum’s summer 2016 exhibition Ten/Forty: Collecting American Art at the Florence Griswold Museum celebrates the range and depth of a rapidly expanding collection of American art. In the first gallery hangs a startlingly bold abstraction in vibrant neon hues painted this year by contemporary artist Peter Halley. On another wall a cluster of sharply delineated pastel portraits created more than two centuries earlier offers hauntingly realistic glimpses of family life and fashion in an influential Connecticut town at the turn of the 18th century.

James Martin in Lyme

Little is known about the pastel artist James Martin, who apparently left England in 1794. The next year he ran an advertisement in the New Jersey Journal describing himself as a “miniature painter from New York, late of Fleet Street, London” and offering to produce portraits in “Oil, Water, and Crayon from $1 to $50.” In 1797 he placed a more detailed notice in the New-York Daily Advertiser: “Portrait Painting, pleasing and striking likeness taken to any size in crayons or pestols [pastels] on moderate terms, at No 8, Wall-street, nearly opposite the presbyterian church, by Mr. Martin, from London. Profile shades taken at 1 dollar each, one minutes sitting only required. Miniatures neatly executed.”[1] If an inscription of unknown origin on the back of one Noyes portrait is accurate, Mr. Martin found customers in Lyme in 1798. Altogether he completed at least seventeen works in town, perhaps on multiple visits, but today only seven have been traced. There are many missing pieces.

James Martin (English, active in America 1794–1820), Eunice Marvin Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Museum Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

His “pleasing and striking” likenesses of Judge William Noyes (1728–1807), Eunice Marvin Noyes (1735–1816), and two of their grandchildren, purchased at auction by the Florence Griswold Museum in 2002, represent only a fraction of James Martin’s work in Lyme. A 140-year old letter tells us that eight other members of the eminent Noyes family, descendants of the town’s first minister, also sat for Mr. Martin. “We have portraits of Judge William and wife and of all his sons and their wifes,” Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824–1900) wrote in 1874.[2] Whatever connection drew the traveling portraitist from New York to southeastern Connecticut has not been discovered, but at least two other prominent local families also commissioned work from the itinerant British painter.

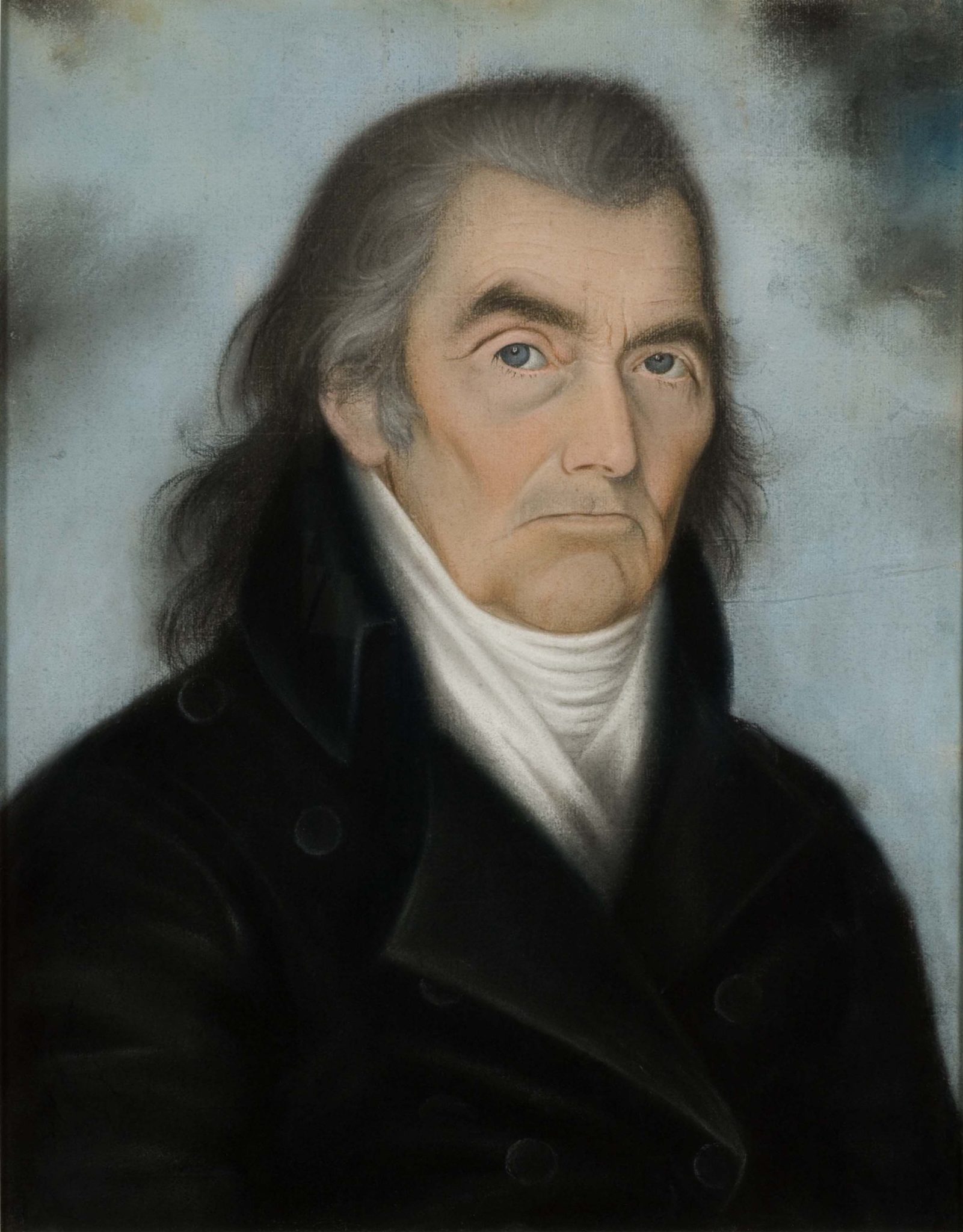

James Martin, Deacon Nathaniel Matson. Pastel on paper. Private Collection.

James Martin, Lois Matson. Pastel on paper. Private Collection.

Deacon Nathaniel Matson (1765–1861), his wife Mary Sill Matson (1768–1802), and his unmarried sister Lois Matson (1772–1825) also sat for portraits, as did two members of the Lord family. Deacon Matson and Squire Lord, like Judge Noyes, played important roles in town and church affairs. All three families occupied spacious homes and owned extensive property, including Negro slaves who served in their households and worked their land. For at least a decade Deacon Matson also owned grist, woolen, and paper mills in the busy manufacturing section of Lyme along Mill Brook.[3]

Nathaniel Matson’s descendants have preserved two of that family’s portraits, but the location of the Lord paintings is not known. Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917) provides detailed descriptions of those portraits of her grandparents in her history of Lyme’s leading families, published in 1892. Mr. Martin, a pastel artist, she writes, painted likenesses of both Richard Lord (1752–1818) and his wife Ann Mitchell Lord (1766–1826). Noting that “they are in the dress of the first years of this century,” Mrs. Salisbury dates the paintings in 1806–7 and observes that “Mr. Lord, then aged about fifty-five, is in a blue coat with a high, rolling velvet collar and large bright buttons, shirt ruffles hanging over the lappels of his coat, a white cambric neckerchief in heavy folds.”

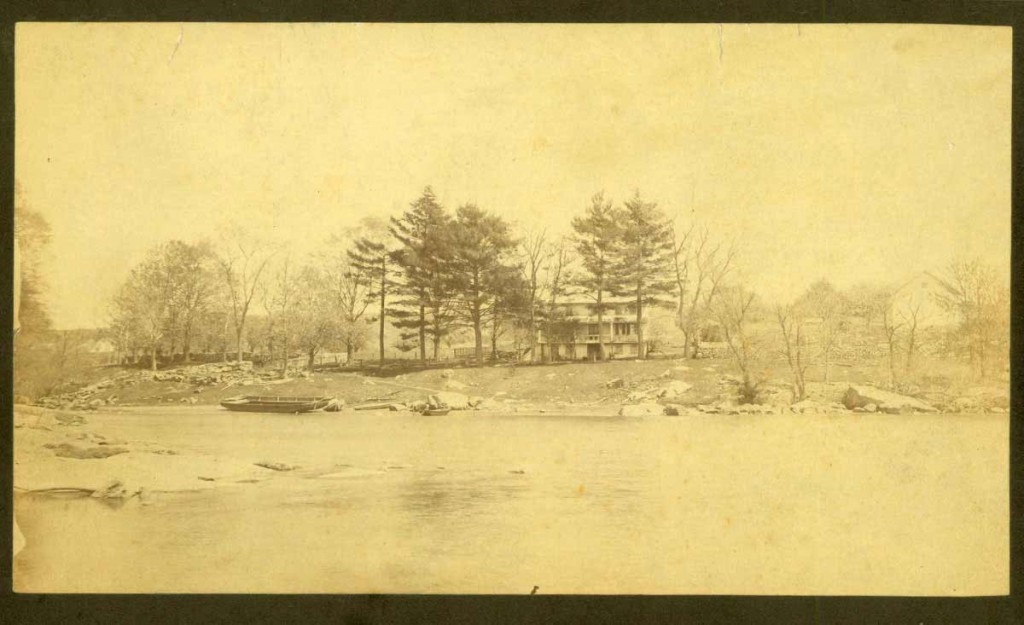

Richard Lord House at Tantummaheag, Lyme Historical Society Archives, Florence Griswold Museum

Glimpsing Lyme’s Past

The four Noyes portraits currently exhibited at the Florence Griswold Museum offer vivid glimpses of Lyme’s past. Judge Noyes served for many years as Associate Justice of the New London County Court, Justice of the Peace in Lyme, and clerk of the Congregational Church. A notebook containing Lyme’s Justice Court records documents his decisions in local civil cases over sixteen years. For theft of 25 yards of cloth in 1790, he required restitution of the cloth, payment of three times its value, and a fine paid to Lyme’s Treasury. Punishment three years later for “wickedly and profanely cursing” another Lyme resident was a fine “and on failure of payment to be Set in the Stocks Two hours.”[4]

Local anecdotes emphasize Judge Noyes’ strictness. Mrs. Chadwick writes that her father Enoch Noyes (1789-1877) often spoke “of the uprightness, piety and dignity of his grandfather.” When Judge Noyes traveled with his sons on horseback, he took the lead and instructed them to follow behind. On Saturdays he required family members to gather for many hours while he elaborated on Biblical passages. On Sundays he refused permission to pass through Lyme unless a traveler had an exceptional reason for profaning the Sabbath.[5] When Judge Noyes sat for his portrait, he dressed austerely in a black jacket and folded white neck scarf. Mr. Martin captured the powdered hair swept back from his forehead, the stern set of his jaw, his prominent cheek bones and sharply arched eyebrows, and the piercing intensity of his gaze.

Eunice Marvin, who also descended from a landed Lyme family, married William Noyes when she was 21 in 1756. In a string-bound notebook Mrs. Chadwick’s sister Martha Noyes (1833–1874) listed the attributes of their great-grandmother. She described “a person endowed with an uncommon share of good sense” and a “resolution and perseverance in laudable pursuits.” Nine years after her husband’s death, Mrs. Noyes died at age 81 from “a cancerous humor, which she long endured with wonderful patience, & christian fortitude.”[6] The next year her son William Noyes 2nd (1760–1834) freed the last of her Negro slaves. Cruce, or Crausa as she was sometimes known, then 39, had been born into slavery in the Judge’s household in 1778.[7] Cruce was twenty when Mrs. Noyes sat for her portrait wearing a high ribbon-trimmed bonnet, an ochre dress topped with a sheer lace-edged shawl, and a coral bead necklace with matching earrings. In Mr. Martin’s likeness her hooded eyes and down-turned mouth seem to convey sober piety and stalwart resignation.

James Martin (English, active in America 1794–1820), Abigail Leverett Noyes, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Museum Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

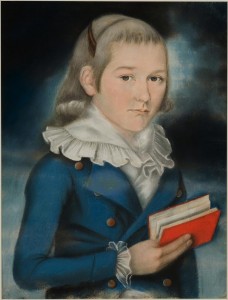

James Martin (English, active in America 1794–1820), William Noyes III, ca. 1798. Pastel on paper. Florence Griswold Museum, Museum Purchase with contributions from Geoffrey Paul, David Dangremond, John & Werneth Noyes, and Gay Myers

The Noyes grandchildren Abigail (1786–1883) and William (1792–1873), ages 12 and 6 when they sat for their portraits if the 1798 date is reliable, left home as young adults for the prospering Albany area. Auspicious marriages promised lives of continued privilege and comfort. During the War of 1812 they returned to Lyme with young families when Abigail’s husband John Sill, like her brother William, pursued commercial opportunities that followed the lifting of Britain’s wartime blockade of Long Island Sound.

To establish his children in Lyme, their father William Noyes 2nd, whose portrait has not been discovered, engaged the talented architect Samuel Belcher (1779–1849), then building an elegant Meetinghouse in town, to design gracious homes on adjacent parcels of Noyes land. Completed in 1818, the stately dwellings assured the stature of the Noyes family’s younger generation. Today the Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts and the Florence Griswold Museum occupy the former Noyes homes.

Neither of the Judge’s grandchildren settled permanently in Lyme. Unpaid customs duties in New York state embroiled John Sill in a decade of legal controversy during which he was confined for an interval in New Haven’s jail. Payment of customs debts, fines, and legal fees ruined him financially, and by 1820 he was forced to sell his home, its furnishings, his carriage and sleigh, and even Abigail’s monogrammed silver. John Sill’s later life is scantily documented, but after years of poor health, he died in Port Chester, New York, in 1852. Left alone after the deaths of her two sons, Abigail moved to Newark, her mother’s family home, far from her Noyes relatives.

William and his wife Hannah raised their four children in the Samuel Belcher-designed mansion considered to be Lyme’s grandest dwelling. Over more than two decades he invested in warehouses, wharves, a blacksmith shop, and a general merchandise store with local partners. Apparently intending to expand his local mercantile interests, he built a prominent brick storehouse on a corner of his estate in 1834. Three years later financial opportunity and family ties drew him back to the Albany area where he invested in a new business with a son-in-law. Whether William maintained contact with his sister Abigail during her decades of family difficulty is not known. Gravestones in New York state mark the final resting places of Judge Noyes’ grandchildren, whom James Martin had painted at a moment of youthful promise.[8]

For her portrait Abigail wore a dress of white cambric softly gathered at the neckline with simple hoop earrings. The artist emphasized her fashionably curled auburn ringlets and used subtle shading around her eyes to add a sense of wistfulness to her quietly alluring innocence. Her brother dressed for his sitting as an adult in a blue jacket and ruffled white shirt, his hair powdered and held with a tortoise shell comb, his fingers conspicuously marking a page in a red book to suggest an interruption in his reading. The portrait of William as a young scholar announces his intelligence and seriousness of purpose, perhaps conveying the expectation that like his father he might someday graduate from Yale.

Much more will be learned about Lyme’s distinguished early residents and the work of a traveling New York portraitist if James Martin’s other commissions in town can be located. The missing pieces have important stories to tell.

Graves of Judge William Noyes and Eunice Marvin Noyes, Duck River Cemetery, Old Lyme, Conn.

[1] Special thanks to Amy Kurtz-Lansing for generous assistance. See Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 (2008). http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/MARTINj.pdf

[2] Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Martha J. Lamb, November 5, 1874, New York Public Library.

[3] Edward Salisbury and Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury, Family Histories and Genealogies (privately published, 1892), p. 304; Susan H. Ely and Elizabeth B. Plimpton, The Lieutenant River (Old Lyme, 1991), p. 57.

[4] Lyme, Connecticut. Justice Court Records, 1790-1806. Connecticut State Library.

[5] Ellen Noyes Chadwick to Martha J. Lamb, op. cit.

[6] Martha Noyes, notebook entry. LHSA.

[7] A note included in the privately held Noyes Family Collection states: “female slave named Cruce granted emancipation Lyme CT 7 January 1817.”

[8] For these and other Noyes family details, see Carolyn Wakeman, Profiles: Abigail Sill Noyes; Exhibition Notes: Albany and Lyme; Landmarks: The Brick Store; Lyme Family Slaves, Part 2—Jenny’s Legacy. Florence Griswold Museum History Blog. florencegriswoldmuseum.org