by Carolyn Wakeman

Featured Photo(above): John Ferguson Weir, East Rock, New Haven, ca. 1901. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM.

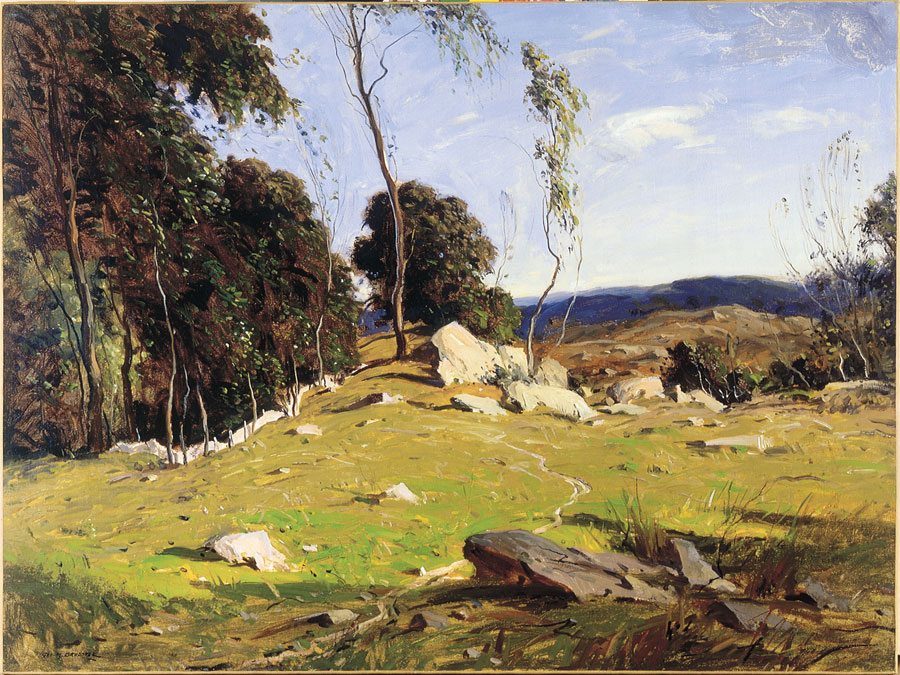

Like the dramatic red-tinged cliffs of New Haven’s East Rock captured on two canvases in the exhibition Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: An Artist’s Guide to the Universe, [1] Old Lyme’s “mineral kingdom” invites exploration. While art colony painters, among them George M. Bruestle (1872–1939), saw the town’s ledges and rock-strewn hillsides as spaces of scenic beauty, the picturesque terrain also had practical uses.

George M. Bruestle, Light and Shadow. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

Artists’ Views

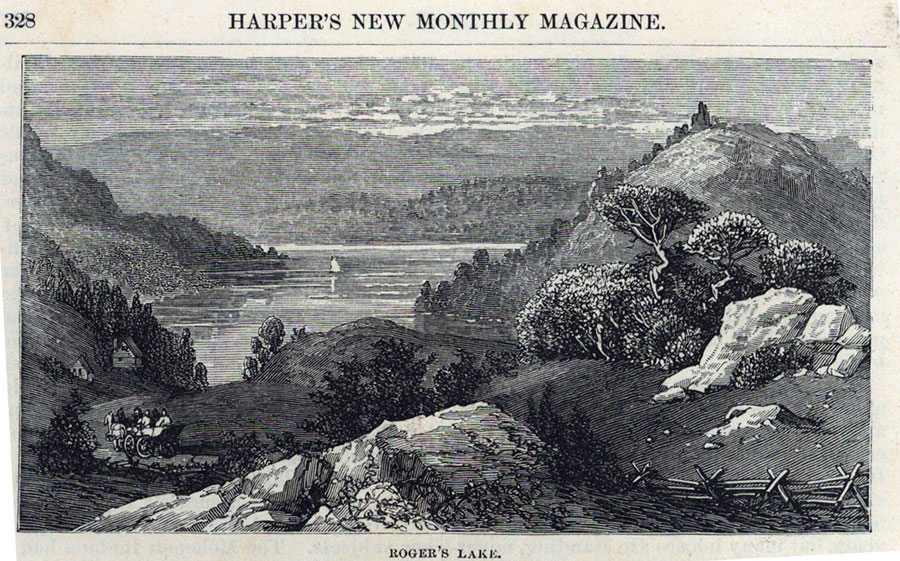

“The variety in the landscape would drive an artist to distraction,” historian Martha J. Lamb (1829–1893) wrote in a profile of Lyme for Harper’s Magazine in 1876. Her article encouraged early tourists to discover “one of the loveliest nooks on the New England coast” and included sketches by an illustrator, likely Charles Parsons (1821–1910), the magazine’s art editor. His view of the rocky promontories above Rogers Lake shows sightseers in a horse-drawn carriage surrounded by “sharp steeps” and “wild crags” as they followed the twisting path of today’s Grassy Hill Road. [2]

Attributed to Charles Parsons, Roger’s Lake, 1876. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, LHSA

Another 19th-century depiction of the landscape includes a rocky bluff, now demolished, that once overlooked the mouth of the Connecticut River. In View of Ferry Point, ca. 1860, Ellen Noyes Chadwick (1824–1900) provides an embellished impression of the wharves, warehouses, and sailing vessels visible from her home on what was then called Noyes Hill. A 1775 survey of the “highway” leading to the ferry locates that “Cragged Ledge of Rock,” [3]. A decade later much of the bluff above the ferry landing was leveled to make way for the railroad. Before a bridge spanned the river in 1871, railroad cars crossed from Saybrook by ferry.

Ellen Noyes Chadwick, View of Ferry Point, ca. 1860. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Krieble, FGM

Ellen Noyes Chadwick, View of Ferry Point, ca. 1860. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Krieble, FGM

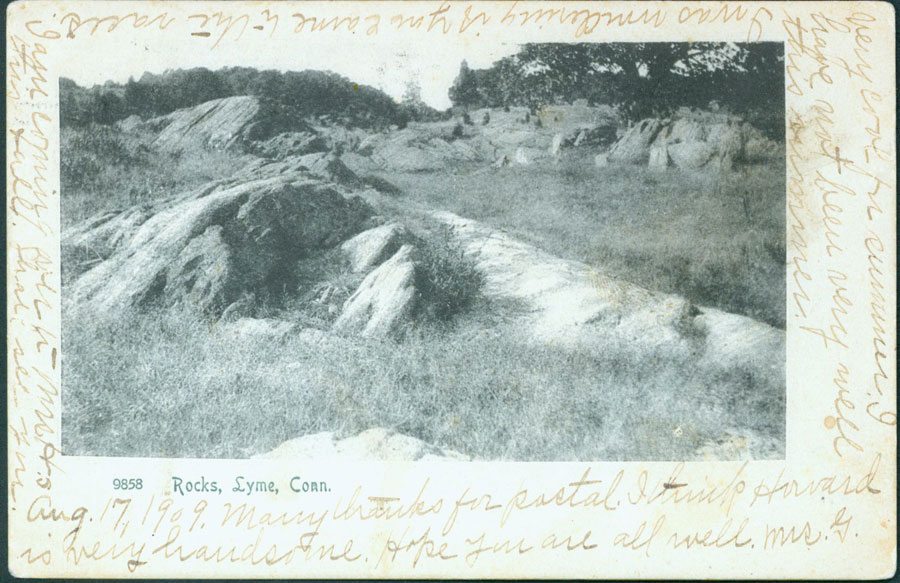

The rock-strewn landscape repeatedly attracted artists and photographers after the turn of the 20th century. Their images of boulders, hummocks, and ledges display startling patterns of light and shadow and convey the shifting moods of the seasons. Whether somber, contemplative, or exuberant, they invite viewers to pause and admire both the intricacies of nature’s handiwork and the resourcefulness of those who worked the land.

Willard Leroy Metcalf,Dogwood Blossoms, 1906. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

Willard Leroy Metcalf,Dogwood Blossoms, 1906. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

Edward F. Rook, Bradbury’s Mill Dam, ca. 1905. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

Ledges and Quarries

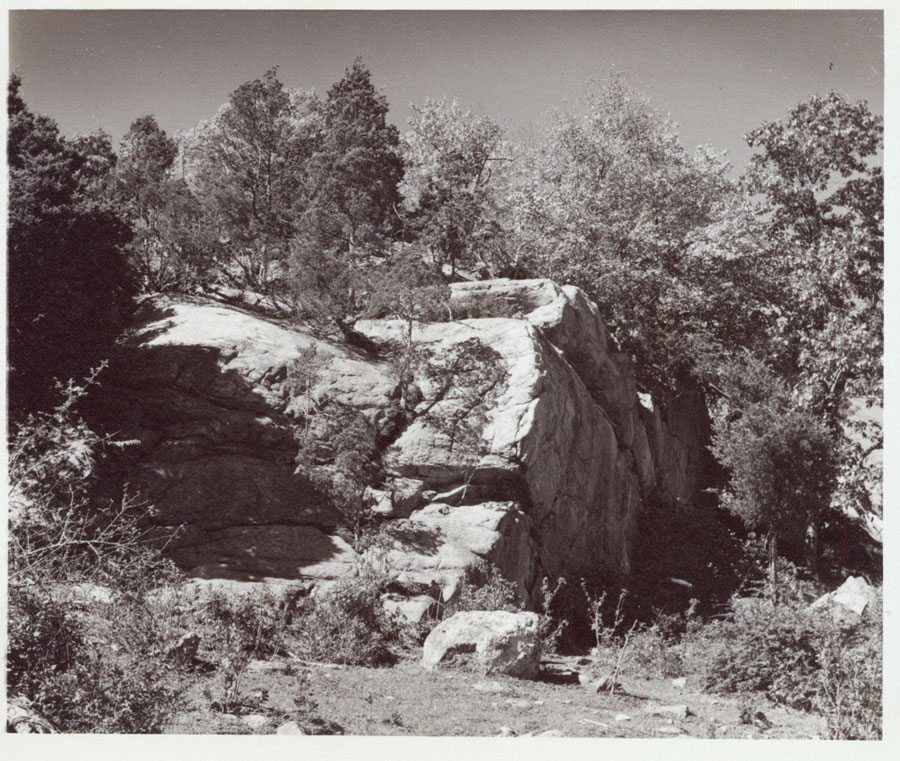

Czikowsky’s, 1948. Album 6, LHSA

Czikowsky’s, 1948. Album 6, LHSA

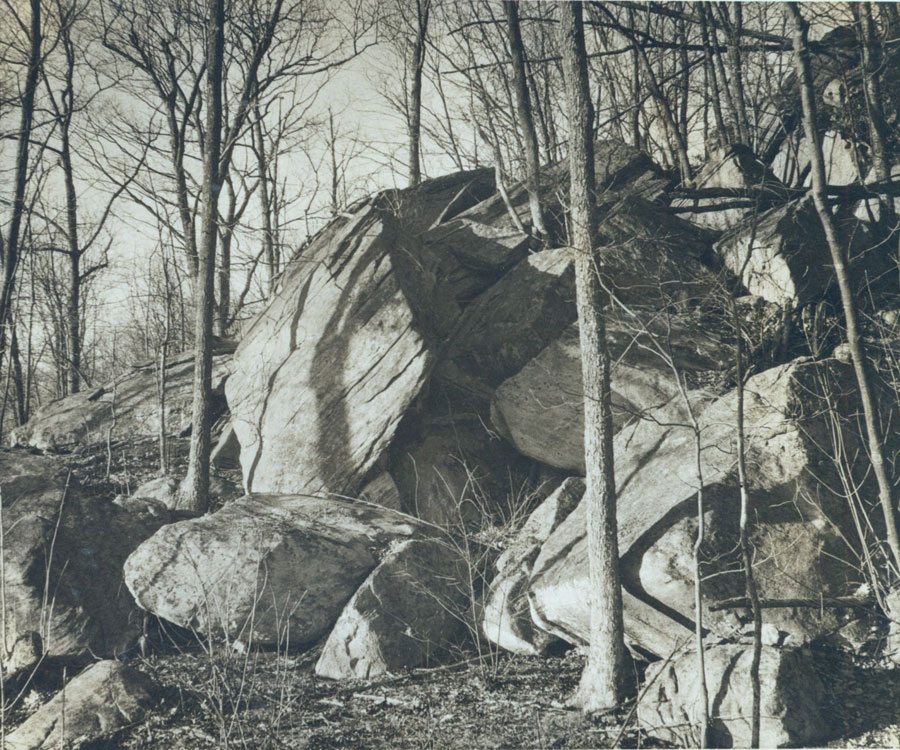

Gungi Road, 1949. Album 6, LHSA

Gungi Road, 1949. Album 6, LHSA

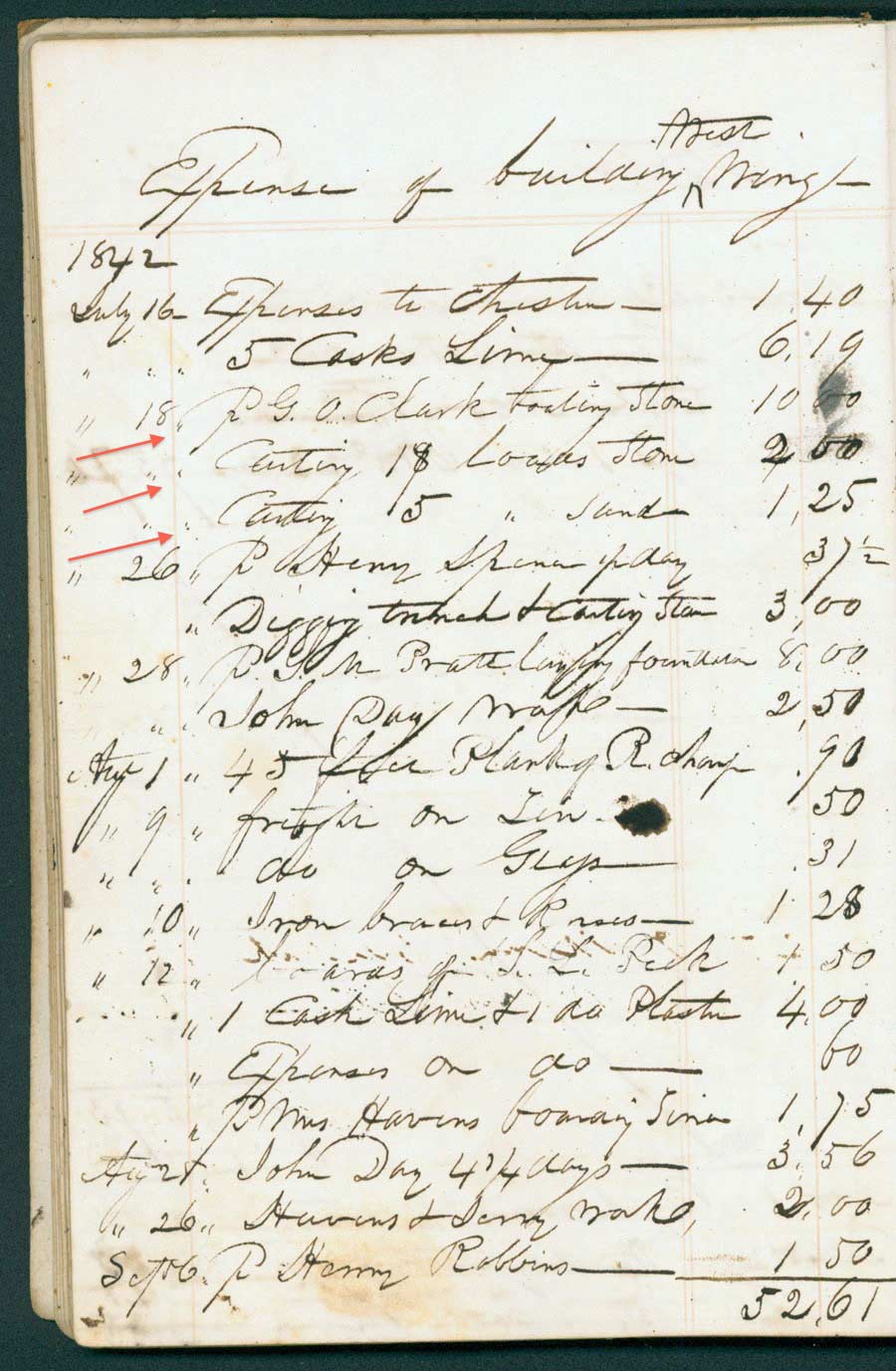

From the time of the early colonial settlement, farmers quarried Lyme’s granite outcroppings and harvested its scattered stones to clear fields for cultivation. Using draft animals and sometimes the labor of indentured servants or Negro slaves, they piled rocks into boundary markers, walls, cairns, and livestock enclosures. Teams of oxen hauled stone to the sites of homesteads, mansion houses, barns, warehouses, and mills where skilled masons fashioned the local rock into foundations, bridges, dams, embankments, and piers.

Childe Hassam, The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1907. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

Childe Hassam, The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1907. Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, FGM

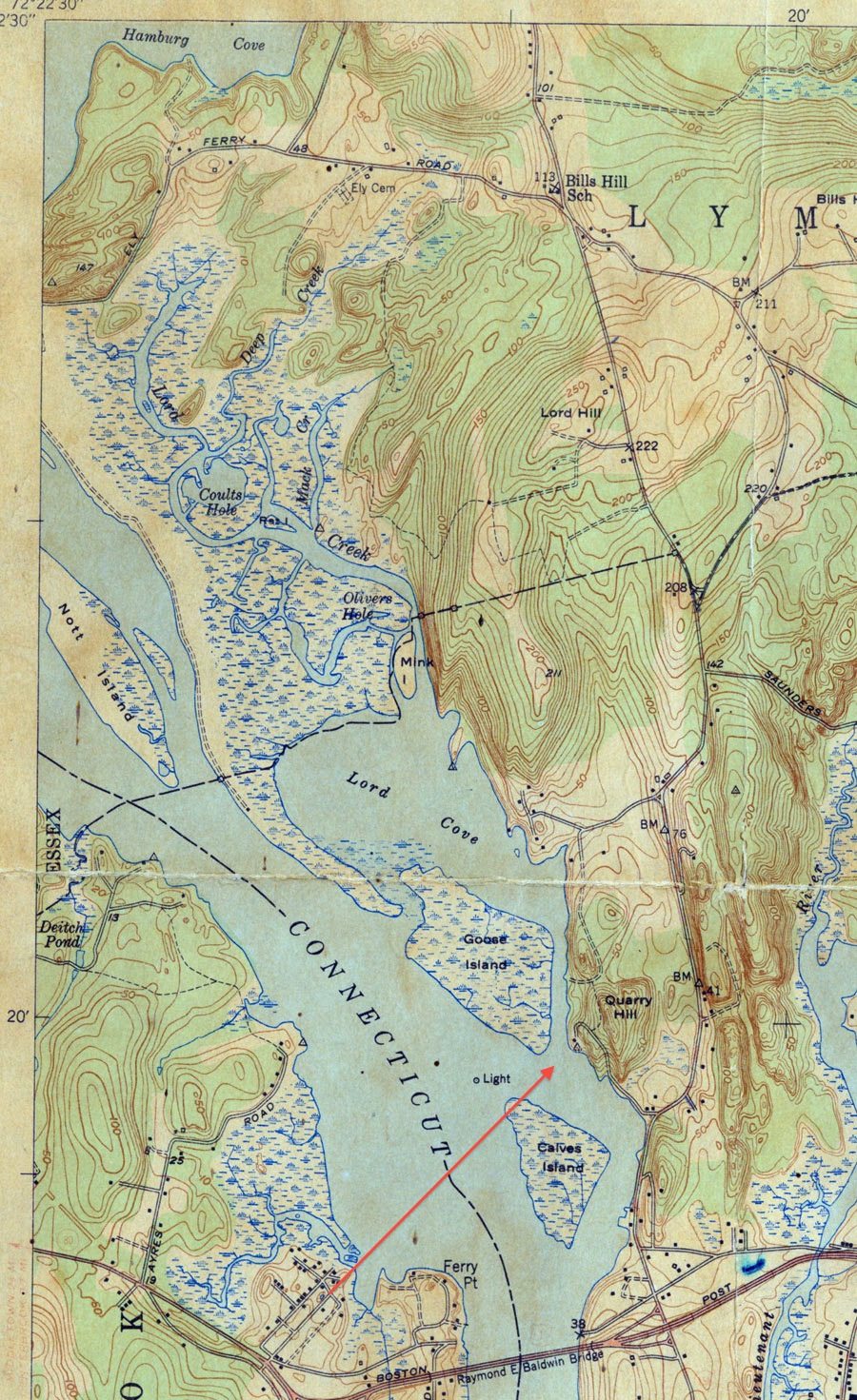

Granite quarries, now overgrown and obscured, once featured prominently in the landscape. A guidebook published in 1907 noted that the “rugged rocks” edging the hayfields in Tantammuhaeg were “formerly the quarries of the Lords and of ‘John Coult, gentleman,’ who built homesteads hereabout.” Farmer and boat builder Henry Noyes (1826–1917) purchased a portion of the former Enoch Lord (1725-1814) estate in 1869, and his acreage included “all that land known as the Quarry and south of the roadway leading to the upper Quarry dock.” [4]

Lyme Quadrant, State of Connecticut Highway Department map, 1951, showing Quarry Hill. LHSA

Lyme Quadrant, State of Connecticut Highway Department map, 1951, showing Quarry Hill. LHSA

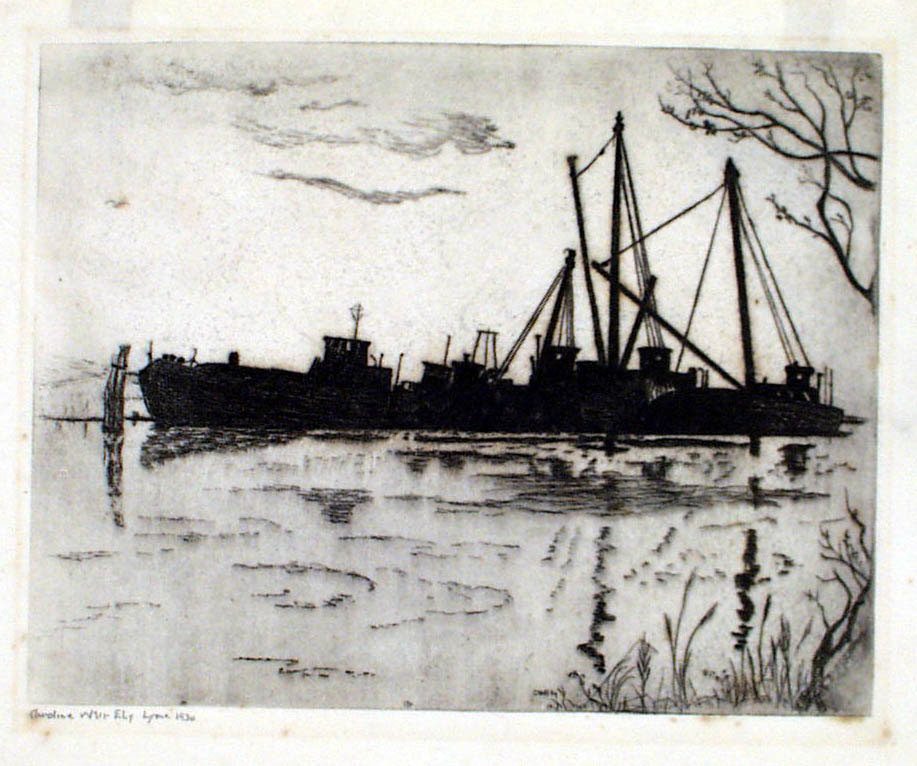

Caro Weir Ely, Quarry Boats, Pilgrims’ Landing, Old Lyme,1930. FGM, Gift of Mr. Geoffrey Conklin

Caro Weir Ely, Quarry Boats, Pilgrims’ Landing, Old Lyme,1930. FGM, Gift of Mr. Geoffrey Conklin

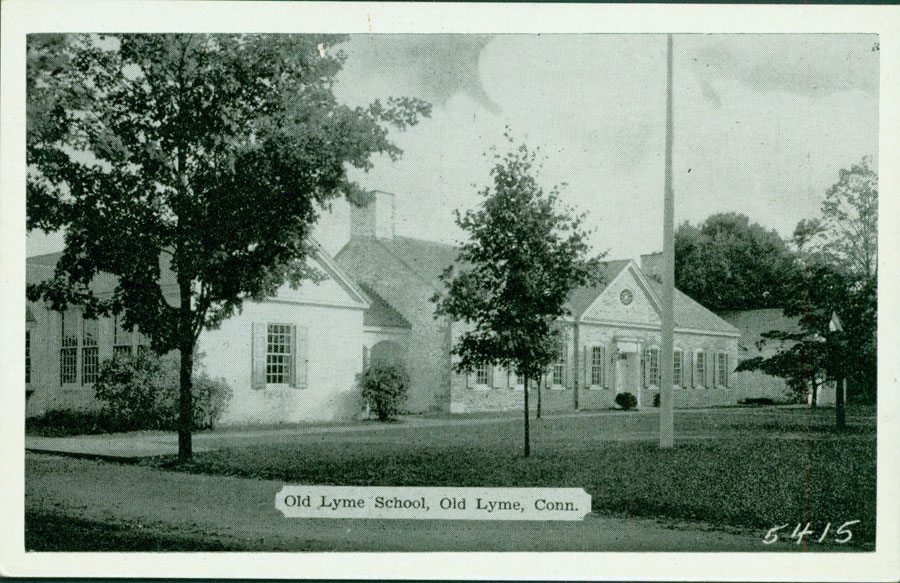

Today above Pilgrim’s Landing on the Neck Road, discarded wheels of granite rest among the weeds near the abandoned quarry dock, but less than a century ago the site was still active. In 1934 the new Center School that replaced an earlier consolidated schoolhouse on Lyme Street utilized blocks of stone hewn nearby.

Allan B. Talcott, The Ledges at Pilgrim’s Landing. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of The Cooley Gallery

Allan B. Talcott, The Ledges at Pilgrim’s Landing. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of The Cooley Gallery

“There were warm days in the summer,” recalled educator and historian Willis H. Umberger (1907–2006), when “a large number of local workmen sat or kneeled on the lawn in the front yard of the demolished wooden building, and hammered and chiseled away at the blocks of pink and grey granite which had been hauled in from a near-by quarry. The larger and darker colored stones were placed on the foundation, and as the front wall rose, the blocks of reduced size, and lighter colors, were selected and added.” [5]

Center School, postcard, 1935. LHSA

Center School, postcard, 1935. LHSA

Stephen J. Lord, Addition to west wing, 1842. Lord Papers, LHSA

Stephen J. Lord, Addition to west wing, 1842. Lord Papers, LHSA

Construction of Memorial Bridge over Black Hall River, 1888. LHSA

Construction of Memorial Bridge over Black Hall River, 1888. LHSA

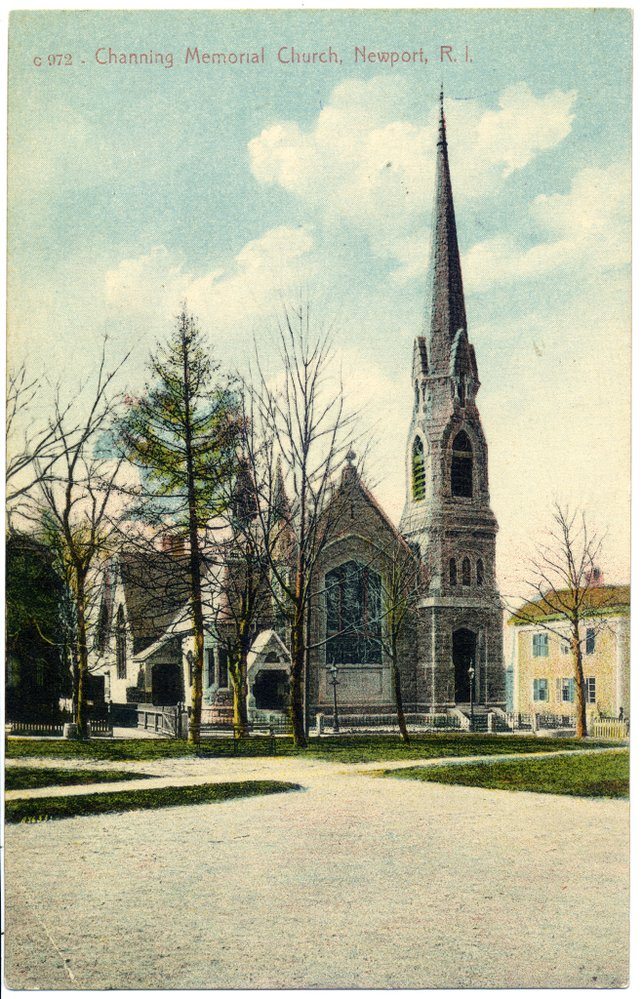

At the southern end of Meetinghouse Hill, a smaller quarry produced a more celebrated stone. Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury (1823–1917) described the red porphyritic granite on her father’s farm as “one of the richest known stones for architectural and ornamental uses.” In 1880 the McCurdy quarry beside Duck River measured “about 50 by 30 feet and from 5 to 10 feet in depth from the present ledge.” The site was never commercially developed, but Charles J. McCurdy (1797–1891) contributed its distinctive granite to build the Channing Memorial Church in Newport, completed in 1881.

Channing Memorial Church, Newport, R. I.

Channing Memorial Church, Newport, R. I.

W. P. Blake (1826–1910), a prominent geologist who analyzed the “carnation red” McCurdy rock, described its special features: “The contrasts between its minerals, the cleavage planes of the large porphyritic feldspars reflecting the light, the iridescence of some of the feldspars and the attractiveness of its general color make this an unusual rock.” he wrote. “It is well adapted for ornamental use, and, when polished, for internal decorations.” Specimens of McCurdy granite were exhibited at the expositions held in Philadelphia in 1876 and in Paris in 1878. “Transportation is by cart about one-half mile to New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad,” the geologist noted. [6]

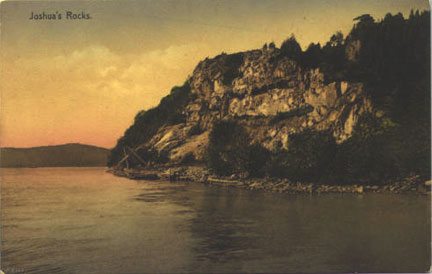

Joshua’s Rock, Lyme. Postcard.

Joshua’s Rock, Lyme. Postcard.

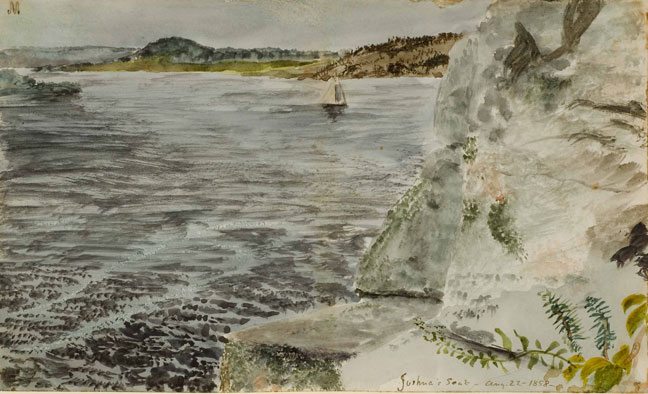

The most active quarrying in the Lyme region occurred at Selden Neck where hundreds of workers in the 1890s produced 3500 paving stones a day for the streets of New York and Philadelphia, as well as granite blocks for the gate house of the Croton aqueduct in New York State. Farther south along the Connecticut River a 60-foot cliff known as Joshua Rocks also produced quarried granite before 1911. Named for the Native American chief Attawanhood, known as Joshua after he converted to Christianity, the cliff face has a natural rock shelf, called Joshua’s Seat, where the sachem is said to have observed fishing activity along the river below. [7]

Charles deWolfe Brownell,Joshua’s Seat, 1858. FGM Purchase.

Charles deWolfe Brownell,Joshua’s Seat, 1858. FGM Purchase.

Sermons and Legends

Rocks, Lyme, Conn., postcard, postmarked 1909. LHSA

Rocks, Lyme, Conn., postcard, postmarked 1909. LHSA

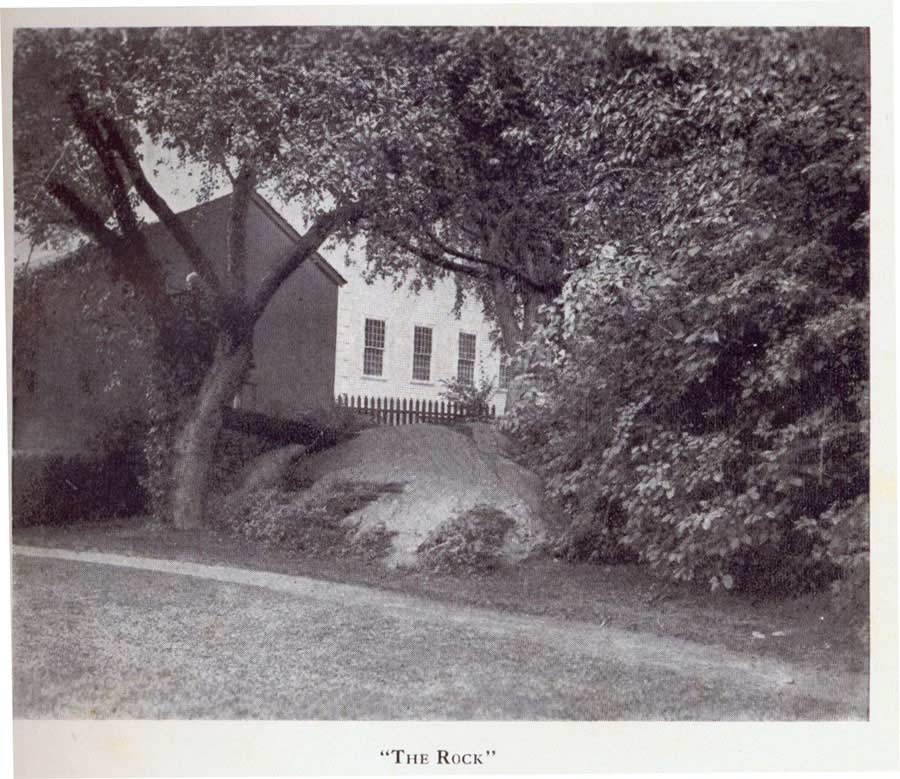

Local rocks sometimes became sites for sermons and temperance lectures. In the 1740s during the revivalist movement known as the Great Awakening, minister Jonathan Parsons (1705–1776) invited English evangelist George Whitefield (1714–1770) to stir the community’s religious passions. From atop a boulder in what was then an open field behind the minister’s home, the impassioned orator delivered his address. Katharine Ludington (1869–1953) remarked in a family memoir that Rev. Parsons had “scandalized the more conservative of his congregation by having his visitor preach to an open air audience, standing on ‘The Rock’ which is still at the back of our house.”

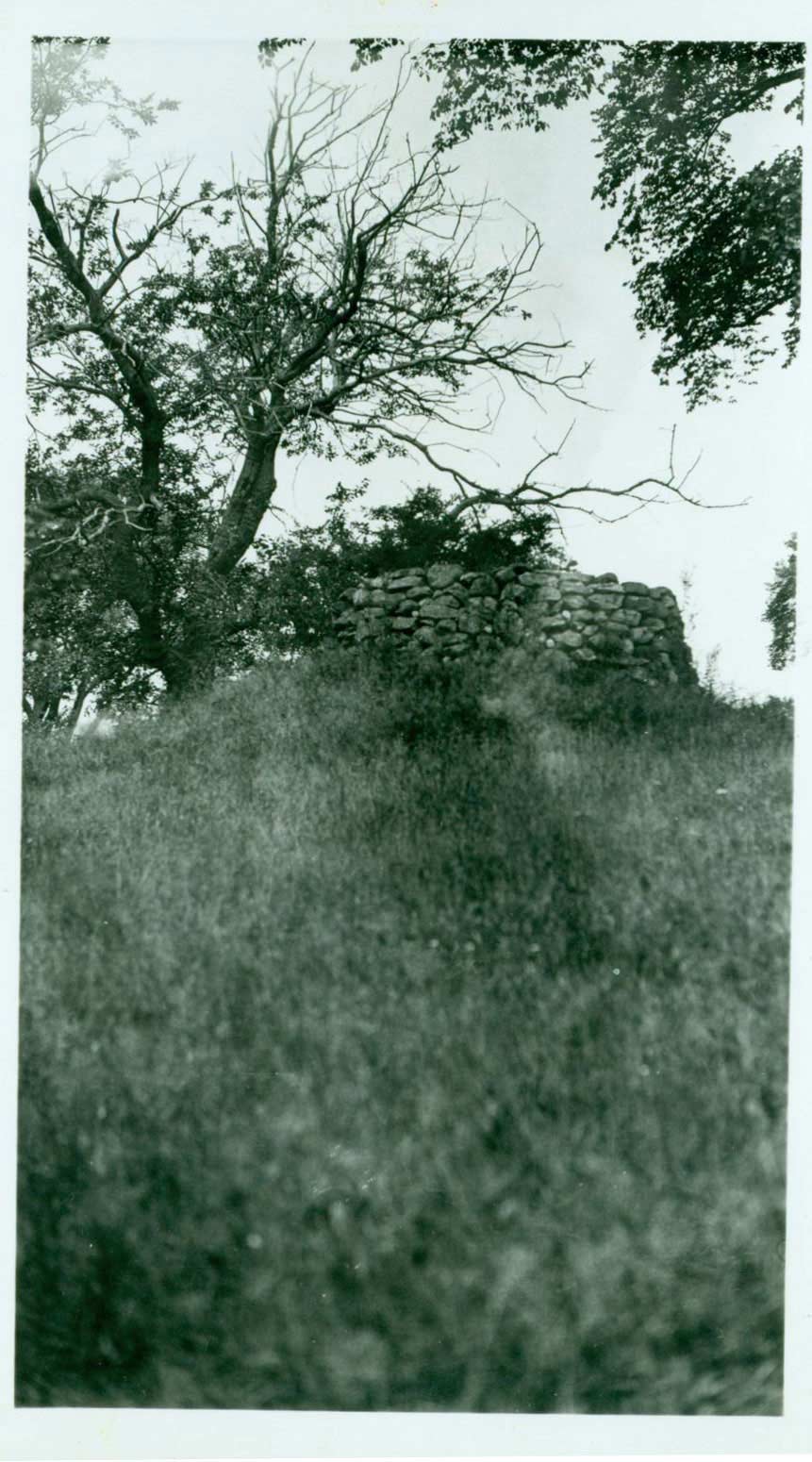

Black Hall cairn, called “Mt. Temperance.” LHSA

Black Hall cairn, called “Mt. Temperance.” LHSA

A rocky elevation in Black Hall also became an open-air platform when Augustus H. Griswold (1789–1836), after a distinguished career as a packet ship captain, delivered rousing speeches to gather support for the local Temperance movement. “There is still standing a cairn, erected on the top of the hill between his house and the road,” Adeline Bartlett Allyn (1846–1915) noted in her Griswold family reminiscences, ”and it was always called ‘the top of Mt. Temperance.’” [8]

“The Rock,” Katharine Ludington, Lyme—And Our Family, 1928

“The Rock,” Katharine Ludington, Lyme—And Our Family, 1928

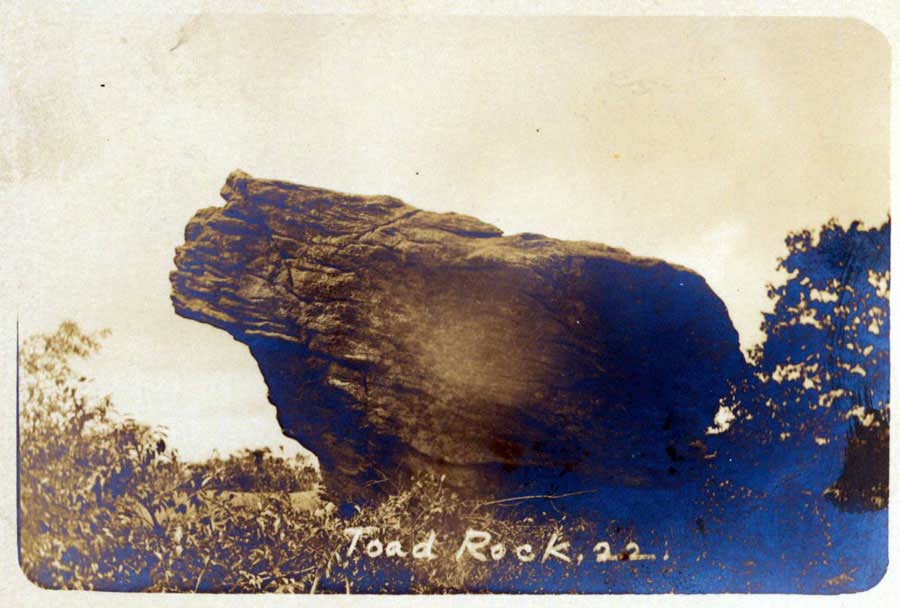

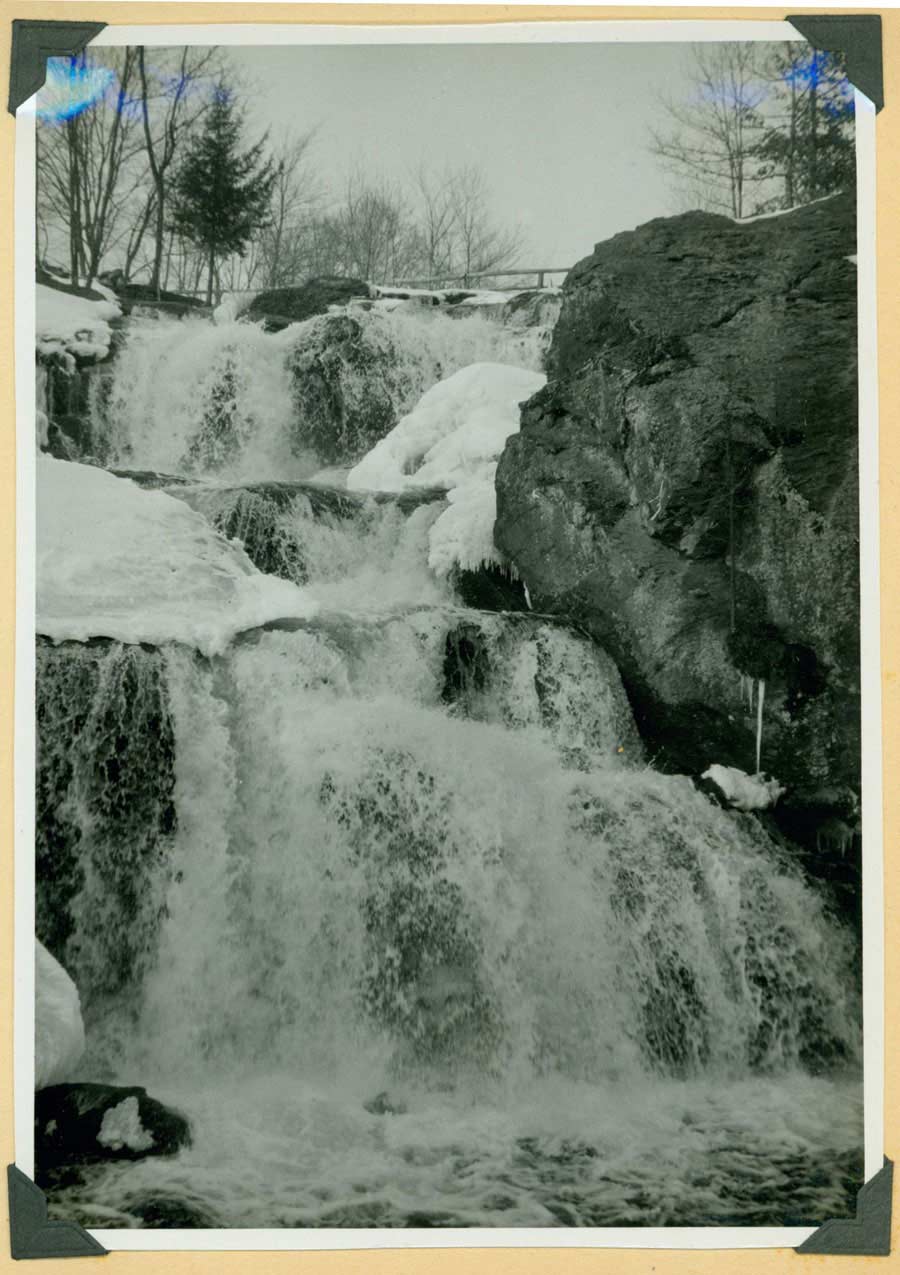

But local rocks sometimes served more playful purposes. Over the decades children of all ages wondered at the mysteries of nearby Penny Rock, Toad Rock, and the Devil’s Hopyard whose curious potholes were said to mark the passing of the devil’s sharply pronged tail. Alluring shapes and crevices drew amateur photographers who recorded family excursions to rocky points along the shore, like Nonsuch on today’s Brighton Road. Local albums also preserved the joyful mood of Sunday afternoon walks to Penny Rock on Meetinghouse Hill where generations of children searched excitedly for pennies believed to grow mysteriously in its cracks and crannies.

Sunday afternoon at Penny Rock. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Sunday afternoon at Penny Rock. Courtesy Ludington Family Collection

Toad Rock, postcard. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

Toad Rock, postcard. Courtesy Carolyn Wakeman

Chapman Falls, Devil’s Hopyard, 1950. Album 6, LHSA

Chapman Falls, Devil’s Hopyard, 1950. Album 6, LHSA

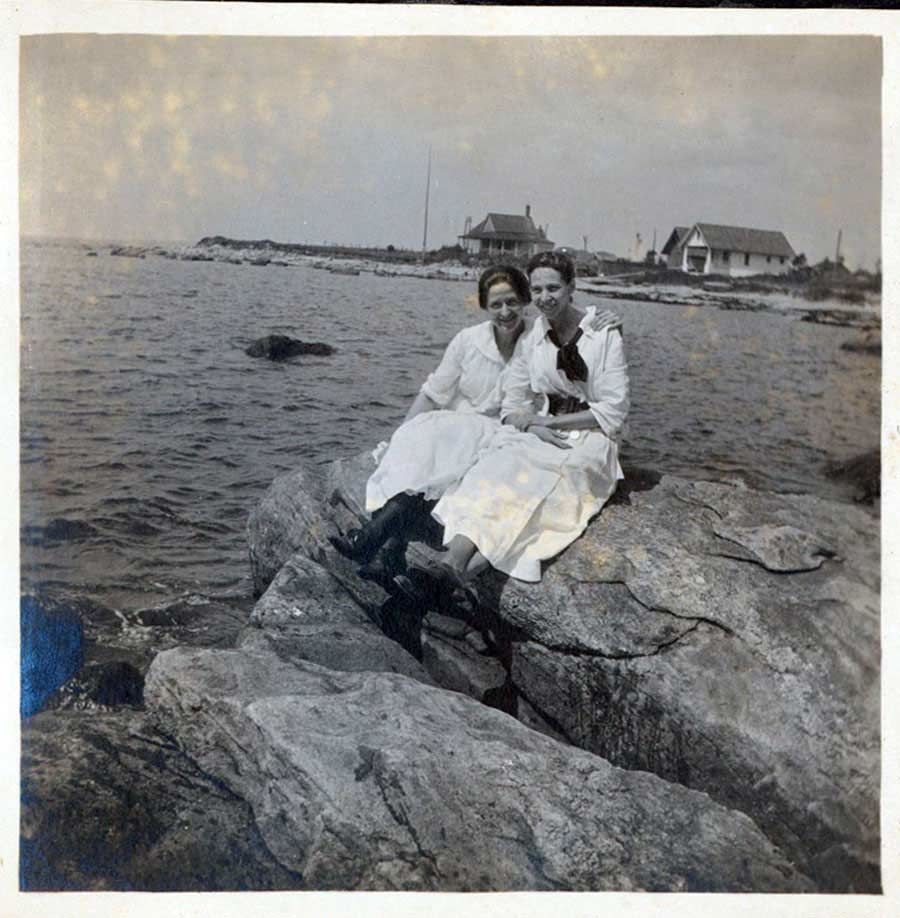

Young women on the rocks. Mary Griswold Steube album, LHSA

Young women on the rocks. Mary Griswold Steube album, LHSA

The “singular precipice called ‘the Jumping-rocks,’” which Evelyn McCurdy Salisbury described as “standing perpendicular some eighty feet above a wet valley,” created a more brooding setting. According to local legend an Indian had jumped to his death there, but below that towering granite face children spent long summer days piling stones to dam the stream and building makeshift bridges across the wetland. [9] Today, protected by the Old Lyme Conservation Trust, the Jumping Rocks at the end of Library Lane remain a distinctive feature of the town’s enticing “mineral kingdom.”

[1] See also George Henry Durrie, East Rock, New Haven, ca. 1862. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, Florence Griswold Museum, FGM.

[2] Martha J. Lamb, “Lyme: A Chapter in American Genealogy,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (February, 1876), Vol. LII, pp. 327–328. Monographs G–Lu, LHSA.

[3] Survey of the highway from the Great Bridge to the Lower Landing used for the Saybrook ferry, January 30, 1755. LHSA.

[4] Katharine M. Abbott, Old Paths and Legends of the New England Border (New York, 1907), p. 54; Old Lyme Land Records 4:69.

[5] Willis H. Umberger, “Center School Elementary: Landmark in a Land of Art,” (June, 1988). Monographs P–Z, LHSA

[6] T. Nelson Dale and Herbert E. Gregory, “The Granites of Connecticut,” United States Geological Survey 484:101–102 (1911). See also: Stone: An Illustrated Magazine, For Producers, Workers, and Users of Stone, Marble and Granite (May, 1889), Vol. 2, p. 4.

[7] “Quarries of Lord’s Island (Selden Island),” The Deep River New Era (August 28, 1892), cited in Peggy B. and George Perazzo, eds, “List of Quarries in Connecticut” (2013). See also Dale and Gregory, pp. 99-100; The Day, August 29, 1911.

[8] Adeline Bartlett Allyn, Black Hall: Traditions and Reminiscences (Hartford, 1908), p. 77.

[9] Recollection of Janet York Littlefield (1921–), August 2013.