By Patty Devoe

Featured Image: Fragments of Wallpaper from Griswold Boarding House, Box 7, Fabric, Wallpaper Etc., Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

Wallpapers of many periods have covered the walls and lined the closets of the Florence Griswold House. And thankfully so. Throughout the years, leftover wallpaper from larger rooms was used in smaller storage spaces. A wallpaper fragment in a hall closet was removed during renovations undertaken in the 1990’s. It was purposely saved and has now been matched with the showpiece wallpaper that graced the front entryway of the house in the late 19th century. This is the story of the research journey which brings that remnant back into focus, back into relevance for the grand Late Georgian house.

A box in the museum’s Lyme Historical Society archives is simply labeled “Box 7, Fabric, Wallpaper, Etc”. It contains several 1.5-inch thick boards with cut nails, plaster lath tracings on the back sides, and wallpaper fragments of a glorious floral design on the front. Nothing in the box connects those fragments to the history of the Florence Griswold House. The first step in reconstructing that story was to identify the wallpaper sample, its design, and its likely date of manufacture or installation.

The “Box 7” wallpaper fragment is an example of decorative design from the Aesthetic movement. The compositional structure is a metallic gold-leaf trellis. The infill is composed of rosette elements, acanthus leaves, and Tudor Roses in an iconic 5-petal format. The infill designs are highly simplified and two-dimensional in the Gothic Revival style. All of these elements are rooted in medieval English history and representative of the arts and crafts design vocabulary originated by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852).

As the decades advanced in the 19th century, new influences from around the world had a major impact on ornamental wallpaper design. The opening of trade with Japan (1854) and construction of the Suez Canal (1869) allowed for the cultural exchange of new elements from Asian, Turkish, Indian, and Egyptian sources. While all design influences were mixed and matched in Victorian times, the “Box 7” wallpaper fragment specifically mixes the Gothic Revival forms of Pugin with a Japanese-influenced color palette, namely the soft pastel colors of light blue, pale yellow, and mossy green. The Japonaiserie colorway and the much favored use of metallic gold-leaf, which lent a warm rich shimmering glow to any room, place this paper in the Aesthetic design period of the 1870’s-1880’s.

A notable aspect of late 19th century homes is the importance of interior design. Middle class prosperity, reduced costs due to mechanized production, and efficient modes of transportation brought European, especially English and French, design trends across the pond. “Americans who had any pretension to fashion were choosing either imported English designs or imitations of them when buying wallpaper,” one expert notes.[i] An advertisement for Hart, Merriam & Company in Hartford in 1877 promoted: “English and French designs embracing the leading styles in gold and silver.” The advertisement noted that: “Formerly painted interiors were much in vogue but to decorate them acceptably involves a far higher order of talent than the frescoers of today possess,” and concluded that “The wallpapers of today have not only artistic merit but by their use a better effect.” [ii]

At the Griswold House the 1870’s brought about a new venture meant to right the financial struggles the family was experiencing. Once a successful packet ship captain, Robert Harper Griswold had retired in 1855, and the family’s fortunes were dwindling. To sustain the family, his spouse Helen Powers Griswold and their daughters established a private school for girls at their home in 1878. It would maintain the highest standards and aimed at attracting the daughters of affluent families. To that end Mrs. Griswold may have felt the need to update and refresh the interior of her home. The “Box 7” wallpaper fragment, representative of the most stylish interior design trends of the day, likely reveals what Mrs. Griswold installed at this time.

Hallway of the Griswold Boarding House, Lyme Historical Society Archives at the Florence Griswold Museum

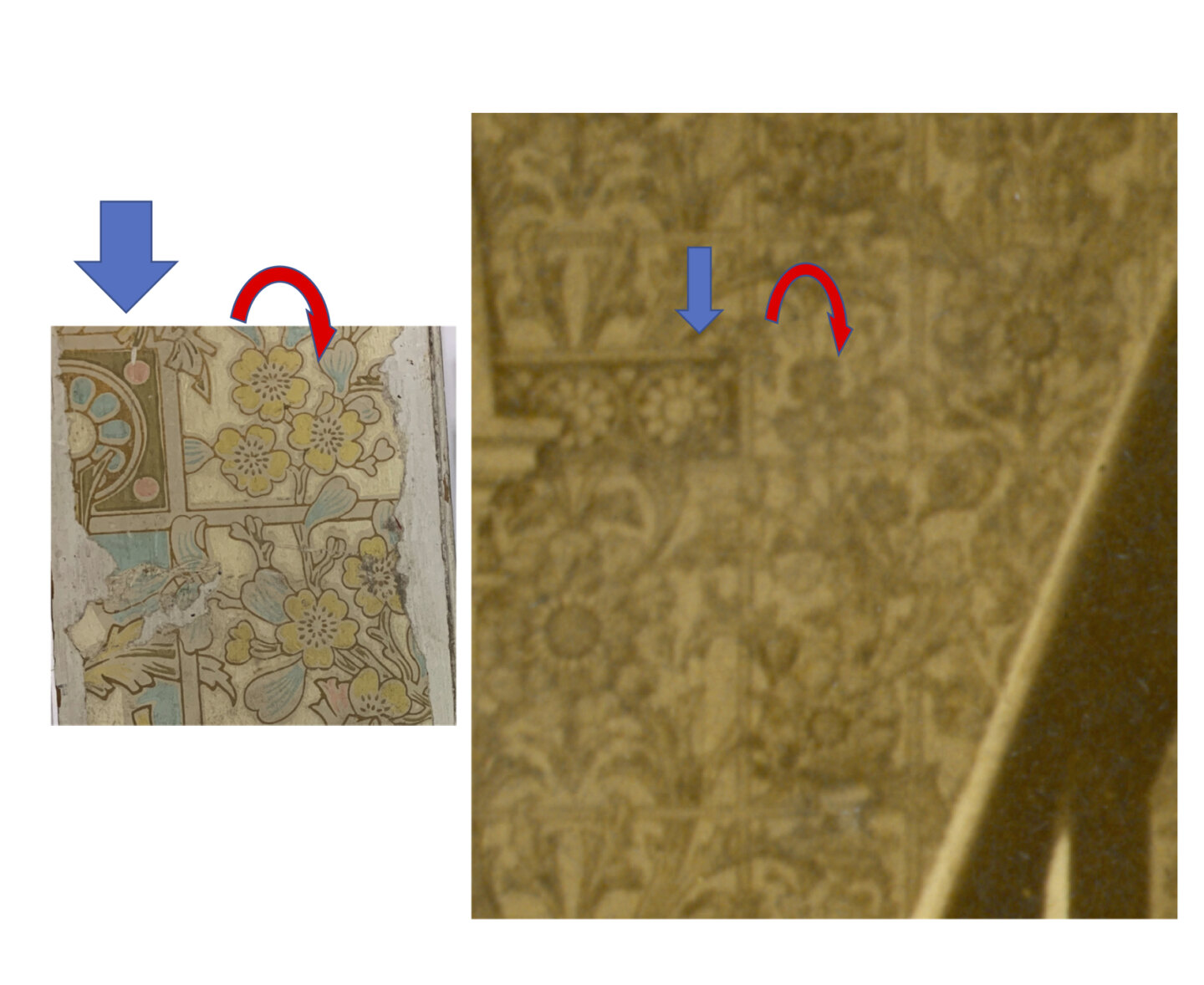

Removed from the walls of a humble hall closet, the “Box 7” fragment was not originally intended for that location. But in what room in the house was it first used? An historic photograph answers the question and shows the design in its full and glorious presentation on the walls of the impressive front hallway of the Griswold House. The color definition has been totally lost in the photograph but is preserved clearly in the matching “Box 7” fragment.

Though the photograph’s date is uncertain, the design firmly places the wallpaper in the 1870-1880’s, which roughly coincides with the establishment of the Griswold home school. The story now comes together to link the wallpaper’s design and its connection to what was happening in Victorian households across the United States with events that shaped the history of the Griswold House.

Comparison of wallpaper sample and detail of historic photograph of hallway

The “Box 7” wallpaper fragment stands on its own as a fine example of the most current ornamental interior design trends of the late 19th century. Being tucked in an out of the way hall closet it did not suffer sunlight or smoke or other damaging elements and retained its bright colors and purity. There is no evidence of where Helen Powers Griswold purchased this paper. Did she travel to New York City or perhaps Hart, Merriam & Company in Hartford? But there is no denying she chose a high quality, stylish Aesthetic paper on par with the selections being made by the best English decorators to make a stunning first impression to guests and visitors of her home and school. This larger story is brought back into focus by the wallpaper fragment removed from a demolition project one hundred years after the wallpaper’s debut.

The author wishes to thank John Tschirch (Rhode Island School of Design) and Amy Kurtz Lansing (Florence Griswold Museum) for their exceptional research assistance, as well as Carolyn Wakeman and Mell Scalzi (Florence Griswold Museum) for editorial and production assistance.

[i] Catherine Lynn, “Surface Ornament, Wallpaper, Carpets, Textiles, and Embroidery”, In Pursuit of Beauty,1987, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, page 67.

[ii] Hartford Courant, 24 February 1877, page 2.