by Emma Flaherty, Wesleyan University, Florence Griswold Museum Intern, Summer 2022

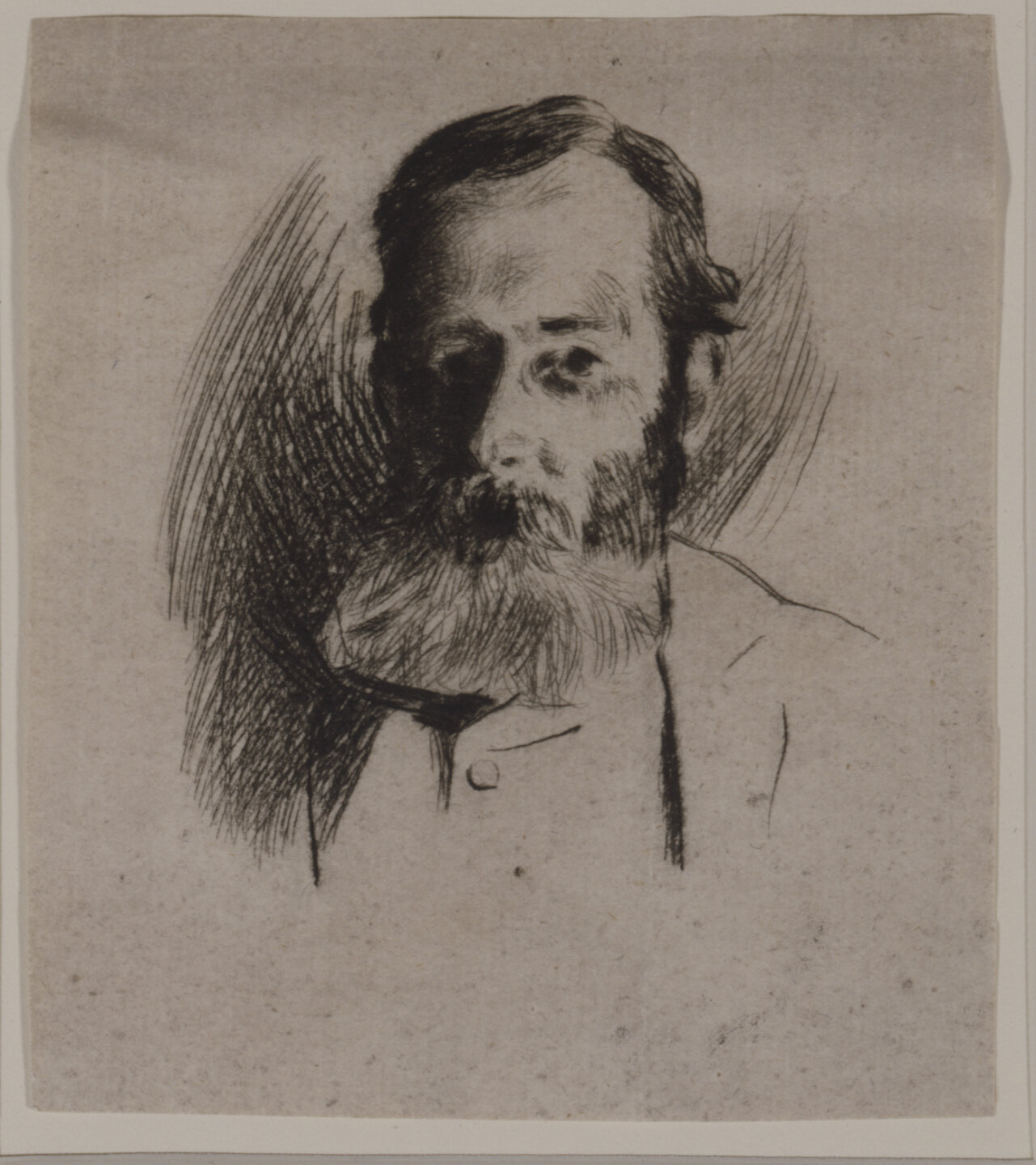

Featured Image: J. Alden Weir, Portrait of Albert P. Ryder, undated. Drypoint on paper, 4 x 3 ½ inches. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Insurance Company, 2002.1.158h

A dry-point entitled Portrait of Albert P. Ryder stands out among the Florence Griswold Museum’s collection of prints by artist J. Alden Weir (1852–1919). It is one of only two prints with a male subject, and also a named subject. It is no surprise that fellow artist Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) joins Weir’s brother, John Ferguson Weir, in that category of named subject, given the dear friendship that Ryder and J. Alden Weir had.

Despite Ryder’s preference for solitude and his hesitancy around friendships and social interactions, the reclusive painter formed a special bond with Weir, whom he met when they were both students in New York City at the National Academy of Design. It was only Weir who could tempt Ryder out of his dark and hidden attic apartment in New York City to escape to the countryside at Weir’s farm in Branchville, CT, now a National Historical Park. Weir even arranged for Ryder’s room to have its own private point of entry, so Ryder wouldn’t have to feel the pressure of interacting with household guests or staff. It is thought that Ryder stayed with Weir at Branchville at least four times, and while Ryder was there, he painted Weir’s Orchard (c. 1885-1890), which is now in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, CT.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Weir’s Orchard, ca. 1885-1890. Oil on canvas, 17 1/8 x 21 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1970.71

After recovering from an illness and spending time at the farm in 1897, Ryder later wrote to Weir, “I have never seen the beauty of spring before… That eloquent little fruit tree that we looked at together, like a spirit among the more earthly colors, is already losing its fairy blossoms, showing the lesson of life; how alert we must be if we would have its gifts and values.”[1] This poetic style of writing is consistent with both Ryder’s mystical presence and symbolic and emotive style of work.

The “Ryder Room,” guest bedroom in the Weir House. Weir Farm National Historical Park, National Park Service.

Julian Alden Weir painting in a field at his Branchville farm. Weir Farm National Historical Park, National Park Service.

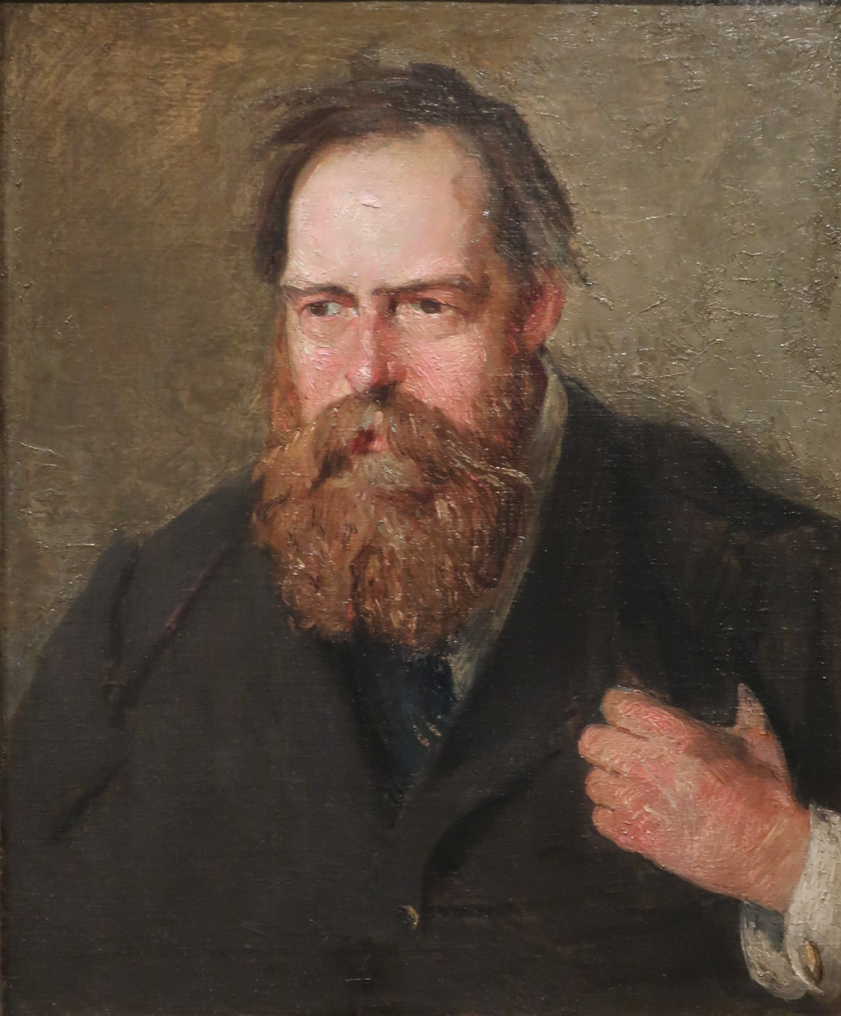

Ryder’s mystical persona was described by author C.E.S Wood, who studied another portrait Weir completed of Ryder when he was appointed to an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1902. Wood described the painting as depicting, “that sweetminded philosopher Bishop Ryder,” to convey the ethereal and other-worldly qualities potently conveyed in Weir’s portrait.[2] Even though Ryder was not a philosopher or a religious leader, he brought the qualities of retrospection and reverence into his everyday life. His description of springtime on Branchville Farm shows that Connecticut was a place where Ryder found inspiration and a different kind of beauty.

J.Alden Weir, Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1902-3. National Academy of Design, New York.

Even though the Florence Griswold Museum’s portrait of Ryder is not dated, one can surmise by visual analysis that the Ryder featured in the drypoint is younger than the man shown in the 1902-3 portrait owned by the National Academy of Design. The drypoint emphasizes his wiry and robust beard and his intense gaze. The ominous shadows around the Florence Griswold portrait seem to communicate with the hatch marks that shadow Ryder’s face, as if to show that he is one with the darkness. Almost the entire left side of his face is masked in black, and it is hard to discern whether he is being consumed by the shadow or is emerging out of it. This mysterious aura seems to follow the course of Ryder’s life, as well as his association with the world of dreams and memories. Just as J. Alden Weir would reuse antique paper from books as support for his portraiture, “…Ryder also found a certain comfort in repurposing utilitarian wood supports, where the residue of life experience still clung to them.”[3]

It was known that Ryder had a history of mental health struggles and “nervous debility,” a topic he discussed at length with his friend and patron Dr. Albert Sanden. It was a common view at the time, one shared by Sanden, that “Nervous Debility” was a disease of “Civilized Men” and caused by the stressors of living life in the modern, developed world. While Sanden’s solution for curing this ill was an electric belt he patented, Ryder’s approach was always more homeopathic. Some remedies Ryder used during his last twenty years, when he was living a nocturnal lifestyle and suffered from insomnia, sore eyes and feet, and gout, included putting cold oatmeal in his shoes to soothe his sore feet, and drinking an excess of buttermilk. Zachary Ross notes how, “Ryder’s ailments were consistent with symptoms of kidney disease, which probably caused his death, but he understood them in a different context, and a language of nervousness inflects his letters.”[4] It is easy to imagine that while living in this world of darkness, being awake and creating and thinking during the nighttime hours, when most people are merely living vicariously through the world of dreams in sleep, Ryder became enveloped in that world. “The artist has only to remain true to his dream,” Ryder declared.[5]

Around the year 1900, Ryder stopped producing new works and instead devoted himself to reworking and repairing old works, no doubt a process that would bring up a lot of memories for the aging master. As he got older, Lebanese poet Kahlil Gibran would often visit Ryder, and would even compose poems to him. Gibran communicated Ryder’s failing health and how, “He told me the last time I saw him that he is painting pictures in his mind. He can use his hands no more.”[6] During this period of amplified reclusiveness, Ryder was interviewed by Adelaide Samson, and snippets of his responses from that interview were included in Broadway Magazine in September 1905. Speaking directly to the idea of memory, Ryder said, “The canvas I began ten years ago I shall perhaps complete to-day or to-morrow. It has been ripening under the sunlight of the years that come and go… it should be pondered over in his [the wise artist’s] heart and worked out with prayer and fasting.”[7]

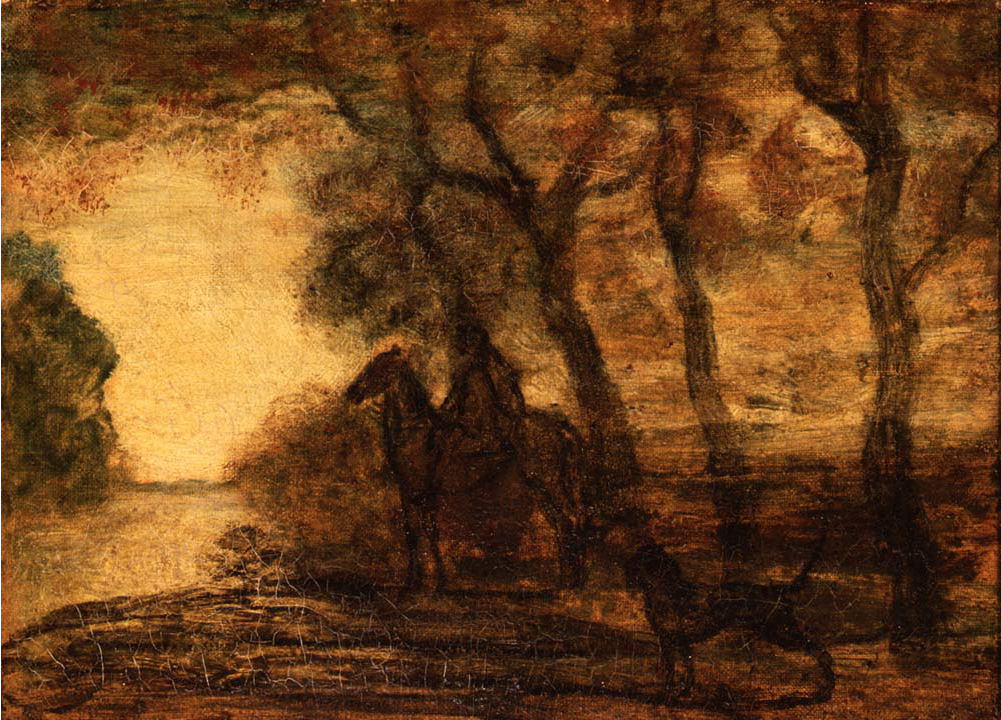

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Equestrian (Portrait of J. Alden Weir), undated. Oil on canvas, 9 x 12 inches. Portland Art Museum, bequest of Winslow B. Ayer, 35.27

Perhaps one of the works that Ryder returned to that had been “ripening under the sunlight of the years” was a quasi-portrait that Ryder made of Weir, titled The Equestrian (Portrait of J. Alden Weir). Was Weir an equestrian? The barn on Weir Farm was known to house farm animals, such as horses, but it has been noted that Weir considered the farm a “hobby… undertaken for aesthetic reasons.” Rather than working the land or tending to the animals, Weir had a “romantic vision” of farm life.[8] The bucolic portrayal of Weir as an equestrian in the landscape is most likely imaginary, and consistent with themes of dreaminess and detachment that appear elsewhere in Ryder’s visionary and ethereal style of painting.

Ryder’s interests and his nocturnal life intersect with the theme of the current exhibition Dreams & Memories, on view at the Florence Griswold Museum, where Weir’s distinctive portrait of this mythic and alluring artist is on display from October 1, 2022 through May 14, 2023.

The author thanks Carolyn Wakeman for her editorial guidance.

[1] “Albert Pinkham Ryder,” U.S. National Park Service, last updated December 18, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/wefa/learn/historyculture/albertpryder.htm.

[2] Doreen Bolger Burke, J. Alden Weir: An American Impressionist (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1983), 246.

[3] Christina Connett Brophy, Elizabeth Broun, and William C. Agee, A Wild Note of Longing: Albert Pinkham Ryder and a Century of American Art (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020), 100.

[4] Zachary Ross, “Linked by Nervousness: Albert Pinkham Ryder and Dr. Albert T. Sanden,” American Art 17, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 89-90.

[5] Albert P. Ryder, “Paragraphs from the Studio of a Recluse,” Broadway Magazine (September 1905): 10.

[6] Brophy, Broun, Agee, A Wild Note of Longing, 218.

[7] Ryder, “Paragraphs,” 10-11.

[8] https://www.nps.gov/places/weir-barn.htm