by Carolyn Wakeman

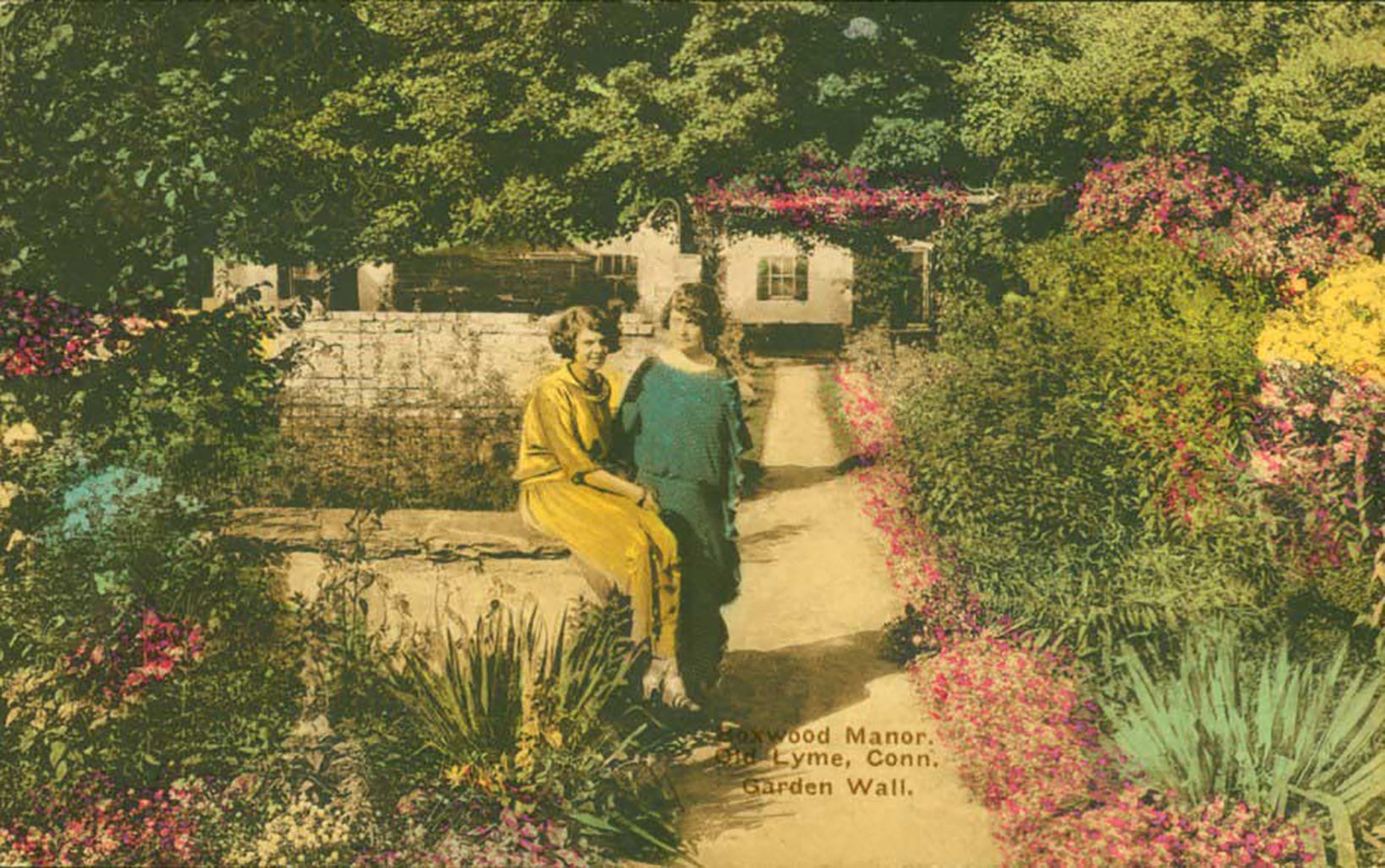

Feature Photo (above): Boxwood Manor, Garden Wall; postcard. LHSA

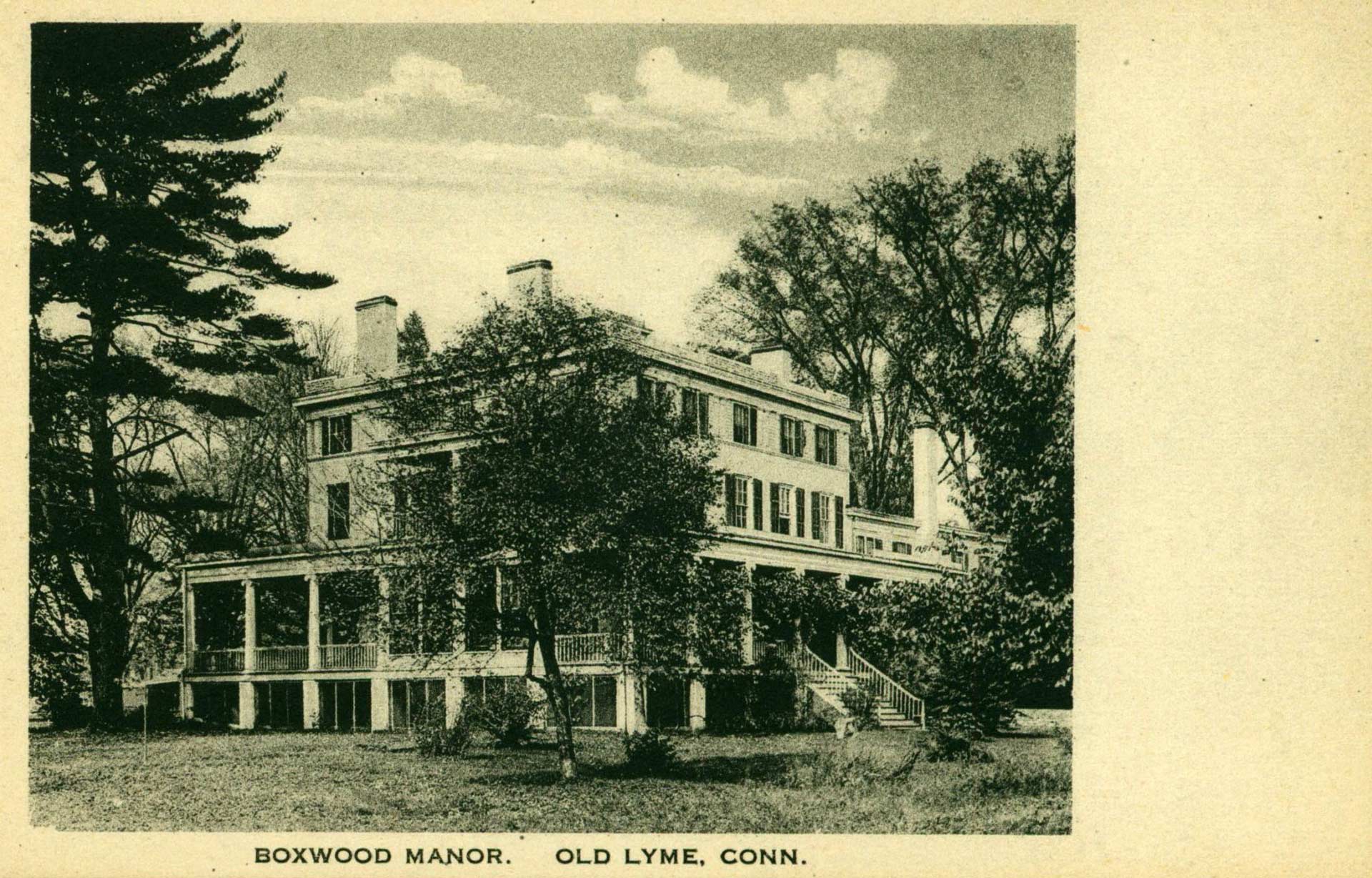

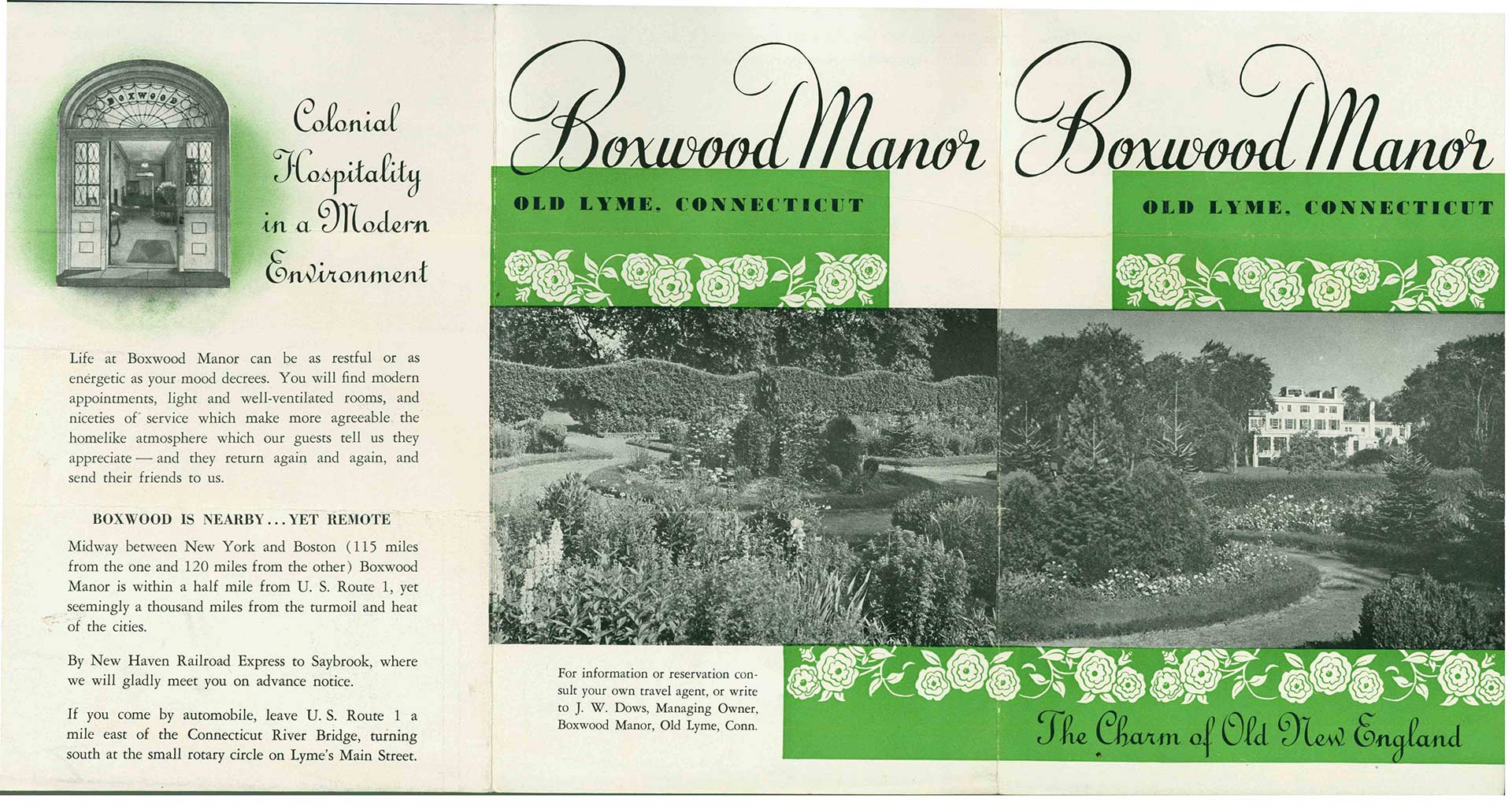

The dazzling displays of Old Lyme’s gardens have captured the eye of painters and photographers for more than a century. Beside village lanes and riverbanks, in formal designs and in cultivated wildness, blossoming gardens brought swaths of color to hotel grounds, country estates, and artists’ dooryards. Postcard views of the flowerbeds, hedgerows, rock walls, and fruit trees at Boxwood Manor became almost a signature image of the town’s scenic beauty in the 1930s.

Home of Richard S. Griswold, Jr.; stereograph. LHSA

Early Glimpses

The boxwood gardens behind the Lyme Street estate of Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., (1845–1904) were well established by 1887 when Old Gardens of Connecticut included a scale drawing “showing the exact location of every cherry tree and shrub and hedge. Even the great goldfish pool was shown with the flagstone base forty feet square and its eight foot or twelve foot pool.” The scale drawing has not been found, but glimpses of the gardens and grounds appear in early photographs.[1]

Boxwood, before additions. LHSA

Boxwood, before additions. LHSA

Boxwood, after additions. LHSA

Boxwood, after additions. LHSA

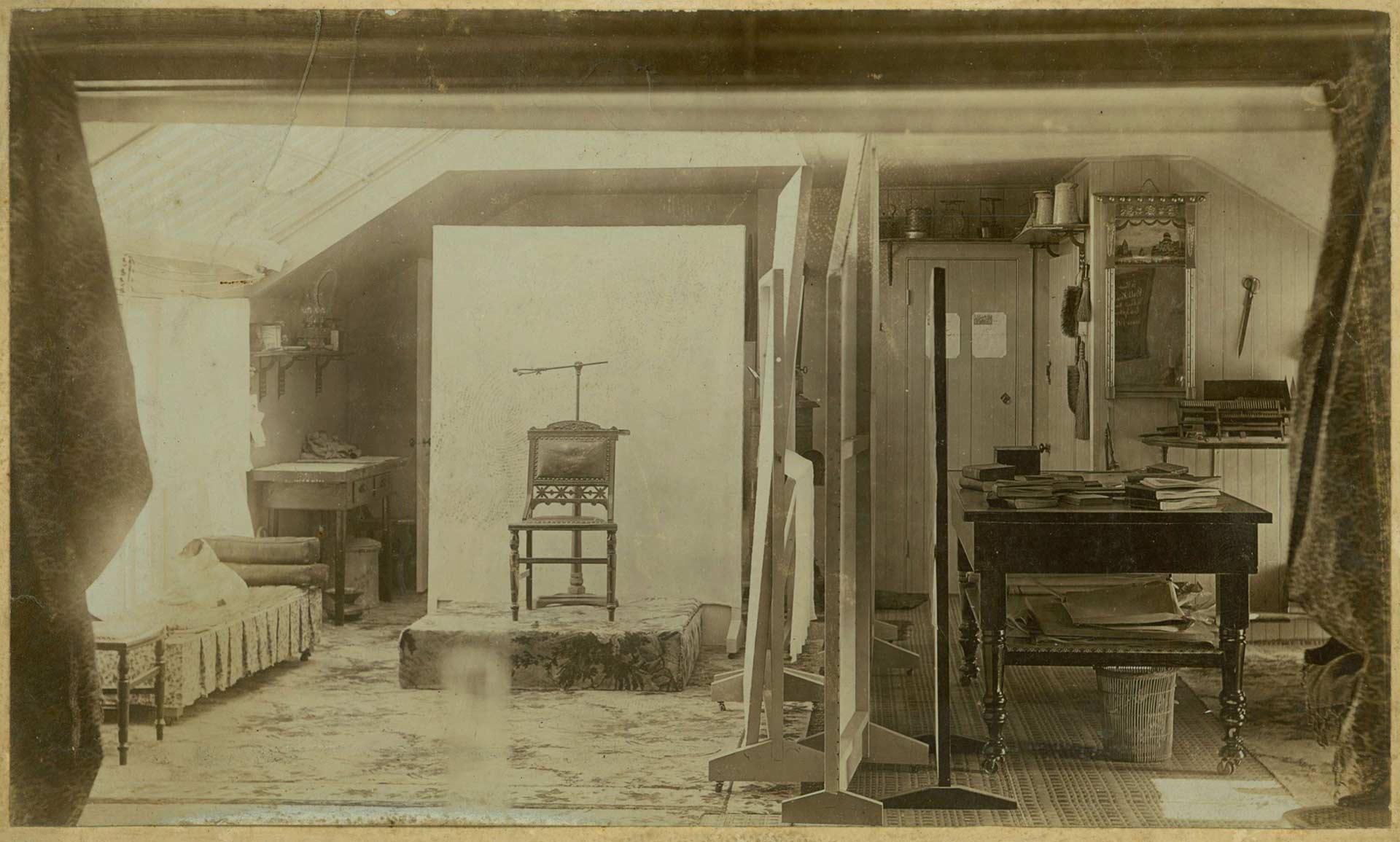

When Richard Griswold retired from the brass manufacturing business in Waterbury and returned to Old Lyme, he expanded the mansion house built for his father in 1842. Besides adding a third story, enlarging the north wing, and installing his gardens, he also set up a “photography room” furnished with a double mahogany table, a day bed, and a decorative chair on a carpeted platform for portrait sittings. Over the next two decades, using the cameras, backdrops, lighting equipment, and drying rack in his home studio, he created an extraordinary visual record of Old Lyme’s buildings and surroundings.[2]

Boxwood, photography studio. LHSA

Boxwood, photography studio. LHSA

Skilled at both architectural and portrait photography, Mr. Griswold preserved multiple images of the interior and exterior of his home, his farm at Tantummahaeg, his eight children at various ages and in different poses, the students at the fashionable Boxwood School for Girls opened by his wife in 1890, and even his collection of model sailboats. But rarely did he focus his lens on details of the natural landscape. Repeated street views of his house show the front trees and shrubbery, but only two images record the rear grounds of the 25-acre estate.

Boxwood, rear barns and fields. LHSA

Boxwood, rear barns and fields. LHSA

Garden at Boxwood, showing greenhouse and garden paths. LHSA

Garden at Boxwood, showing greenhouse and garden paths. LHSA

One image looks across the fields to his barns and locates the graceful church steeple prominently in the distance. Another looks beyond the greenhouse and through the apple trees to the elegant formal patterning of the boxwood-bordered paths. But it was structures and people, not plantings, that drew his eye. The vine-draped veranda that later became a favorite subject for Lyme artists is scarcely visible in a portrait of Boxwood School students seated on the steps.

Boxwood School students on veranda steps. LHSA

Boxwood School students on veranda steps. LHSA

Artists at Boxwood

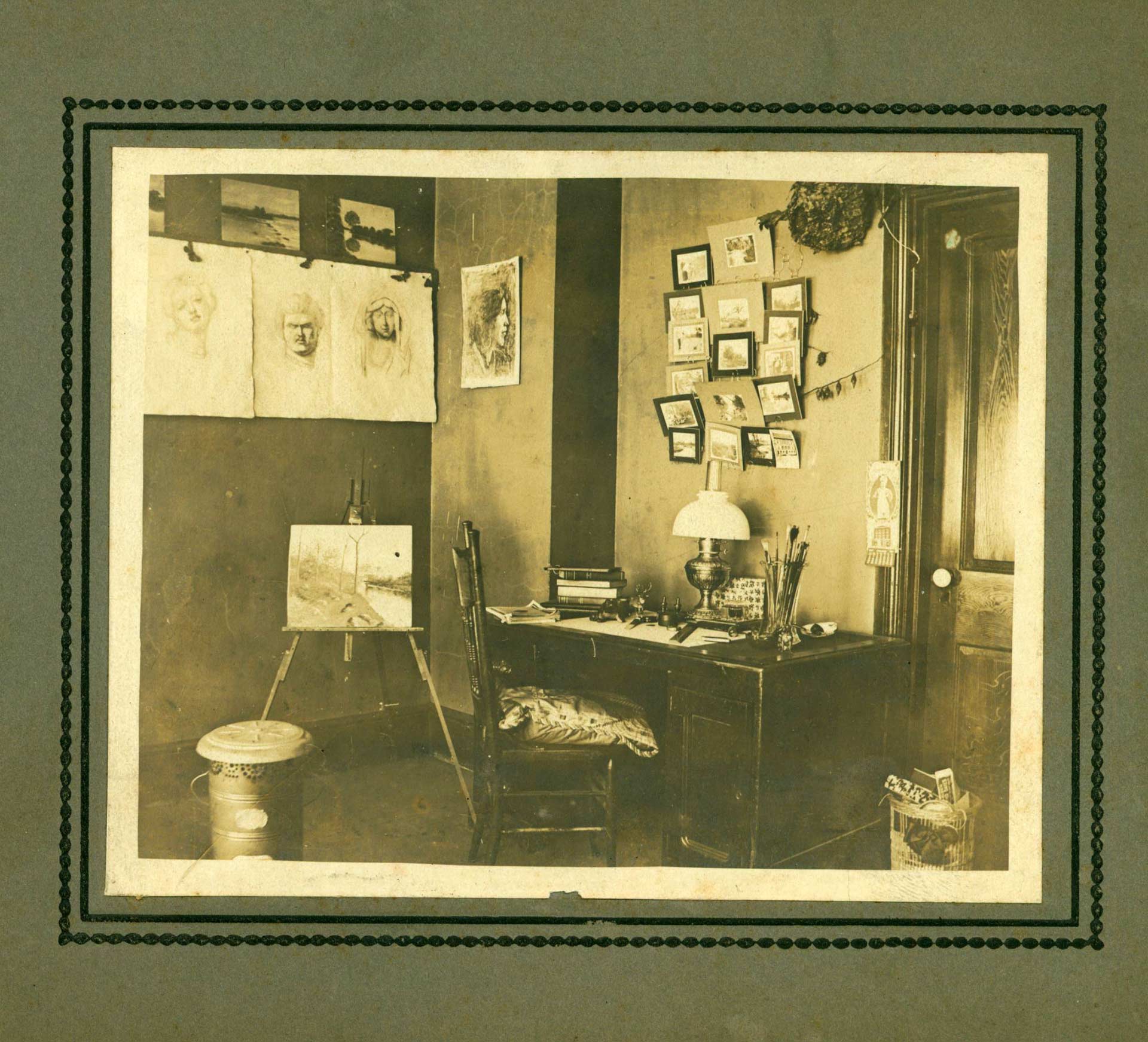

Boxwood played an important supporting role in the development of the Lyme art colony, and already in 1896 Mrs. Richard Griswold (1849–1907) advertised the Boxwood School for Girls as offering “Special advantages in music and art.”[3] The arrival of the Art Students League’s summer school in 1902, which brought the town “a new title to distinction” according to The New London Day, established an ongoing link between “beautiful ‘Boxwood Hall,’ half hidden behind evergreen hedges and great old trees,” and the artists who visited in growing numbers. What became known as the summer Lyme School of Art held studio classes in 1905 at Boxwood, where artists could rent rooms when the boarding students were not in residence.[4]

Art room at Boxwood. LHSA

Art room at Boxwood. LHSA

The art colony’s founders had settled in the stately home nearby where Florence Griswold (1850–1937), a cousin, encouraged and promoted their work, but several prominent painters rented rooms at Boxwood. William S. Robinson (1861–1945) and Charles Vezin (1858–1942) who arrived in Lyme in 1905 were among its lodgers, as was Ellen Axson Wilson (1860–1914). During her family’s first stay in Lyme that year, Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), then president of Princeton University, booked room and board at Boxwood for the three-month season while his wife enrolled in the summer art school.[5]

Boxwood Manor; postcard. LHSA

Boxwood Manor; postcard. LHSA

Mrs. Richard Griswold’s death brought the closing of the girls’ boarding school in 1907, but the art students continued to meet at what would soon become a thriving summer inn. “The students at the summer art school held an exhibition of their season’s work at the Boxwood studios,” The New London Day reported in 1910. “One of the pleasing features of the exhibition, besides the general excellence of the pictures, was the successful manner in which the room had been decorated.”[6]

Alumnae from Mrs. Griswold’s school gathered to celebrate lasting friendships and share happy memories of “dear old Boxwood” in 1912. Several teachers returned for the occasion, including artist Abraham L. Laiblin (1872–1916) who had a studio nearby on Ferry Road. The New London Day covered the weekend activities and noted: “Mr. Laiblin who will be remembered as a teacher of art and is still living in Lyme was also seen at the Inn.”[7]

Painted Impressions

By then the columned Boxwood veranda had become a favorite subject for Lyme artists. Mary Bradish Titcomb (1856–1927), who had recently studied in Paris and Philadelphia, spent the summer of 1905 in town, perhaps living at Boxwood where she painted two views of the veranda. The twelfth summer art exhibition held at the town’s public library included The Veranda: Boxwood Manor in 1913.

Mary Bradish Titcomb, The Veranda: Boxwood Manor

Image: New York Times, September 7, 1913

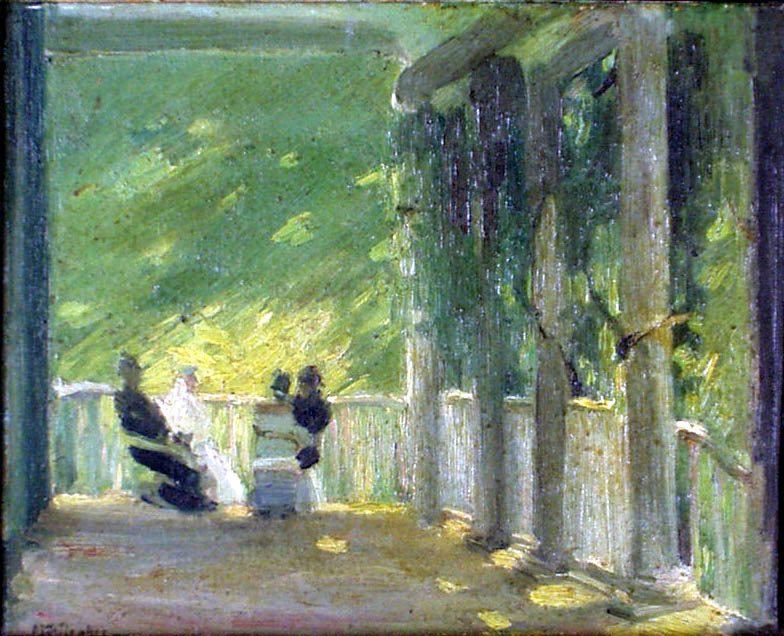

The New York Times’ reviewer praised Titcomb’s skill and described her entry as “a clever painting of light splashed by shadow, and the group of girls sewing and reading are bathed in the warm half light of a place only partly sheltered from the sun’s intrusion.” In a second view of the veranda, which later acquired the misleading title The Park Bench, Titcomb captured a scattering of women guests, perhaps summer art students, sewing, reading, and conversing undisturbed in the vine-shaded enclosure of the porch.[8]

Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, The Porch. Private Collection

Mary Bradish Titcomb, The Park Bench.

Courtesy Bonham’s and Butterfield’s

The intimate porch space became a subject for two other women artists attracted to Lyme. Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones (1865–1968) may have painted the veranda during her visit in 1906, as The Porchwas exhibited at the National Academy of Design the following year. Her depiction of “several ladies seated in the sunlight and shadow of a colonial porch,” according to a reviewer, was the “most unforgettable canvas in the show.”[9] For Marion Farwell Tooker (1882–1935) the vine-shaded expanse of the porch rather than its occupants became the primary subject. In her Boxwood Veranda the four women in white rocking chairs who cluster near a shaft of summer sunlight seem almost to recede into the surrounding foliage. [L5.14]

The inn and its summer residents disappeared entirely from Edmund Greacen’s (1877–1949) Boxwood Manor, likely painted in 1910 when he started working in Lyme.[10] Already recognized for his paintings of the floral landscape in France, where he had rented a house for two years near Monet’s gardens in Giverny, Greacen captured the veranda’s luxuriant foliage in silvery tones of green, pink, cream, and gray. Allowing the cascading leaves and blossoms surrounding the stairway to fill the canvas, Graecen created an alluring portrait of Boxwood’s rear entryway.

Marion Farwell Tooker,Boxwood Veranda. Florence Griswold Museum

Lyme artists continued to lodge, teach, and paint at Boxwood during its years as a fashionable country inn. Guy Wiggins (1883–1962) offered painting classes and gave studio talks there during two summers, and Charles Vezin rented Boxwood rooms even after buying a 300-acre farm on Grassy Hill.[11]

Edmund Greacen, Boxwood Manor. Private Collection

Charles Vezin painting Boxwood gardens. LHSA

Meanwhile the gardens became one of the town’s most celebrated attractions. Katharine Ludington (1869–1953), a neighbor who maintained her own luxuriant gardens adjacent to the village church, preserved a captivating photograph of an elegant woman wearing a brocaded Chinese jacket smiling among the blossoms. On the reverse she noted in pencil: “One of the present Boxwood boarders, in the garden.”[12]

Boxwood gardens, 1927. Courtesy of the Ludington Family Collection

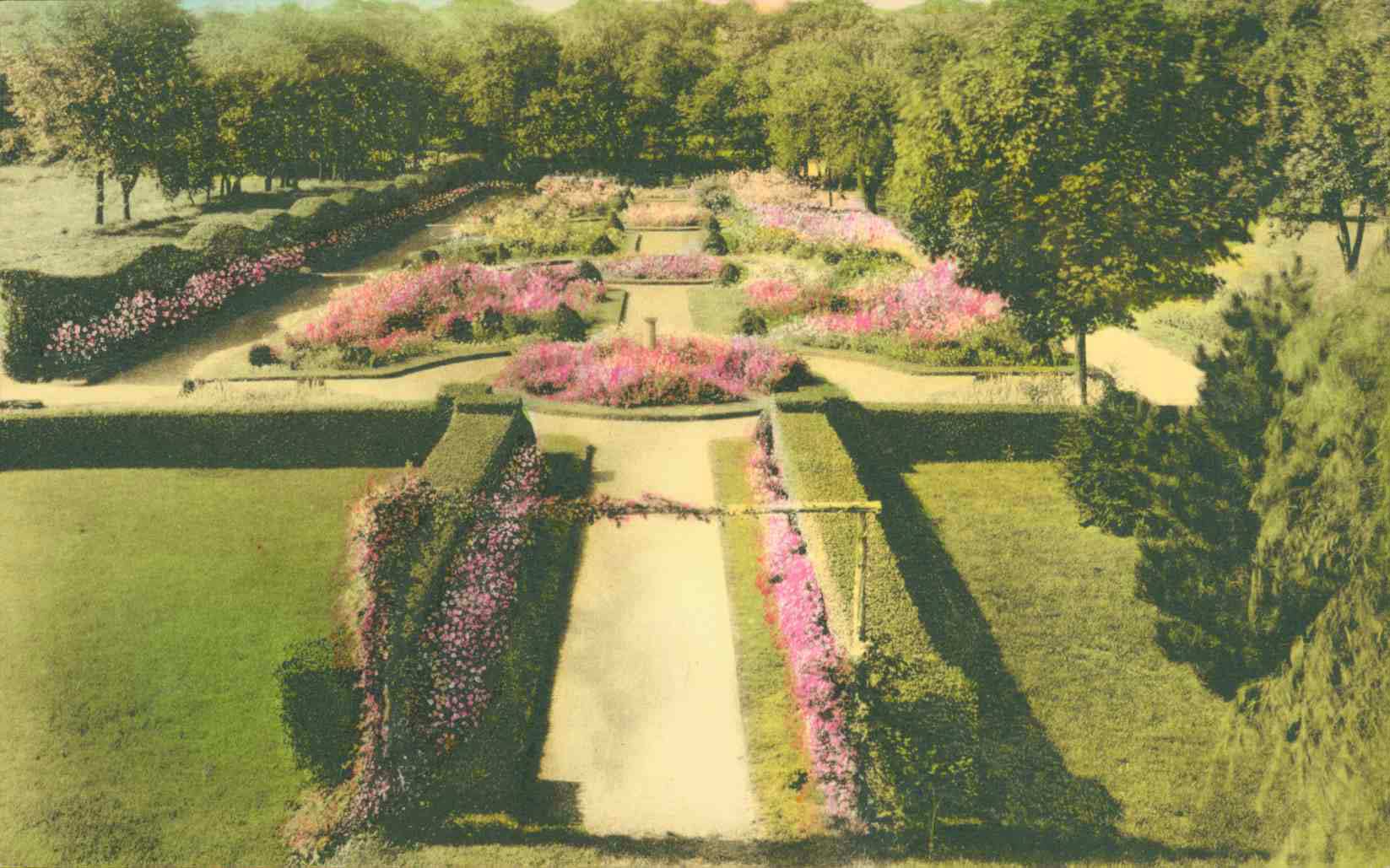

When managing owner J. W. Dows redesigned the hotel grounds, he reflected changing tastes in garden style as well as his own vision. Mounded flowerbeds in brilliant color enlivened the more subdued Victorian plantings on the Griswold estate, and an ornamental obelisk replaced the once prized fish pool. An illustrated brochure promoting the hotel’s varied attractions described the main house, or manor, as “surrounded with extensive lawns, stately elms, row upon row of boxwood hedges, and exquisitely lovely English gardens.”

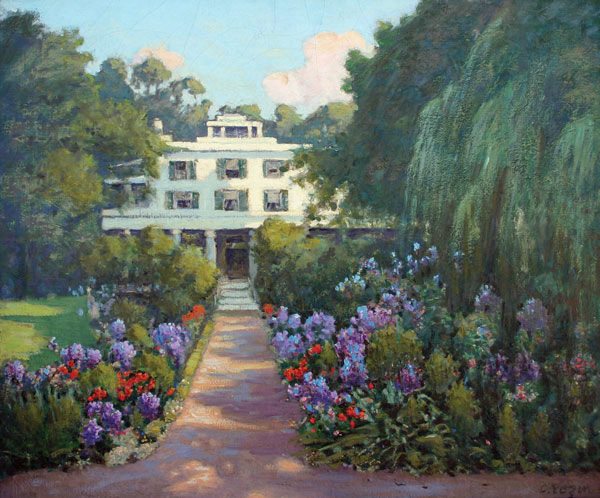

When Charles Vezin painted Gardens at Boxwood in about 1927, he chose not the intimate space of the secluded veranda but the broad sweep of the rear grounds in the fullness of summer bloom. Adopting vibrant primary colors rather than the muted tones favored in earlier views, he used the inn’s bright white façade, sharply delineated, as a backdrop for the crimson and purple display of the central flower-bordered path.

Charles Vezin, Gardens at Boxwood. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of The Cooley Gallery

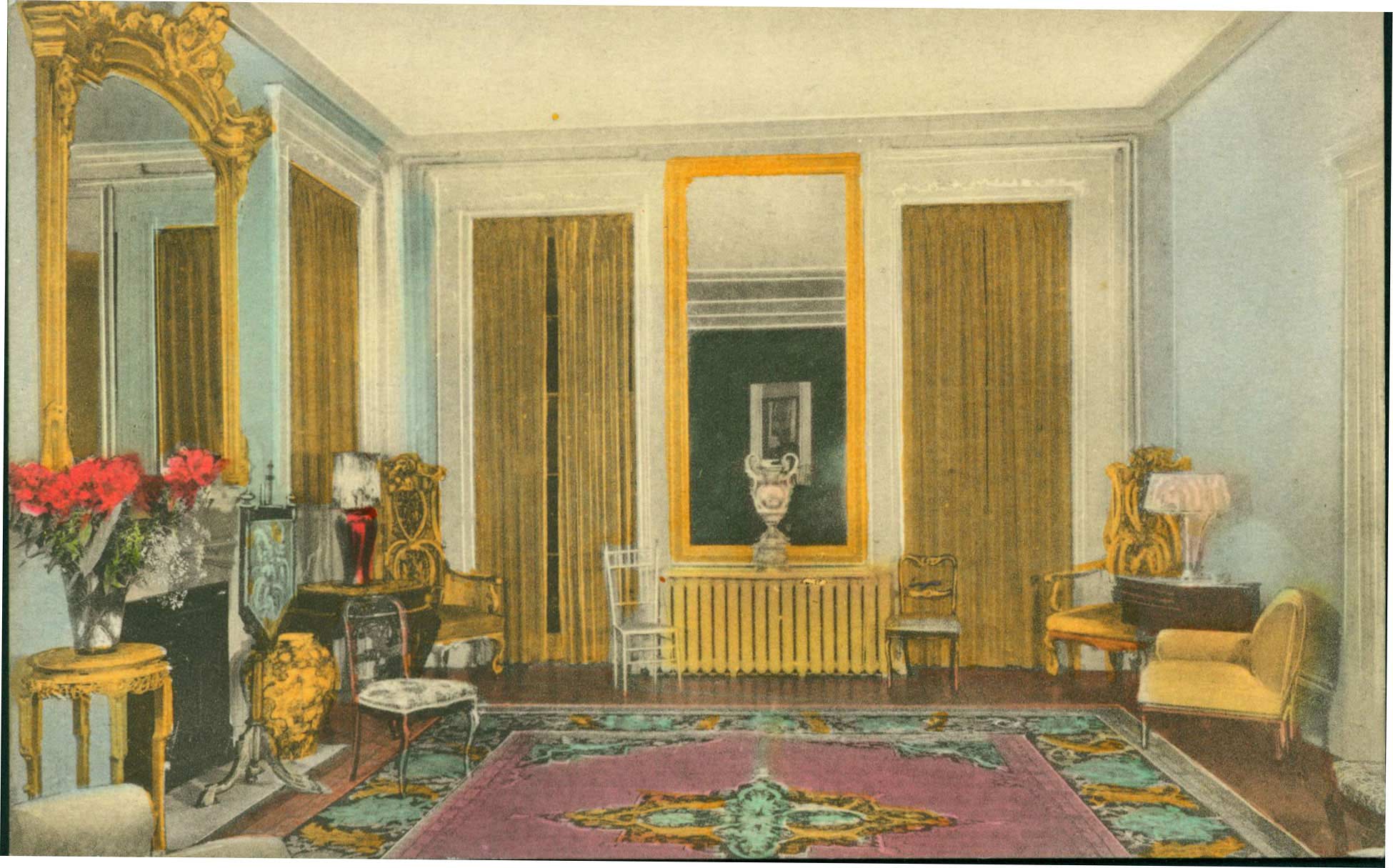

Vibrant color also defines Vezin’s interior view of a graciously furnished Boxwood salon. In his impression of The Music Room, the rich red tones of a decorative carpet convey an aura of warmth, elegance, and refinement. The painting also suggests a lasting affection for the historic estate where Lyme artists had painted for more than twenty years.[13]

Charles Vezin, The Music Room.

Florence Griswold Museum; Gift of Fenton L.B. Brown

Boxwood Manor, Music Room; postcard. Courtesy Jennifer Hillhouse Collection

But it was postcard views of Boxwood blossoming that announced Lyme’s scenic beauty to a broader audience. In the 1930s and 1940s guests sent colorful postcard greetings that publicized the charm of the country inn and displayed its resplendent gardens from multiple angles. Mr. Griswold would perhaps have been startled to see the alterations to his grounds, with his distinctive goldfish pool removed, his cornfields dotted with tennis courts and cottages, and his original boxwood gardens lavishly enhanced by flowerbeds, trellises, and rock walls.

Boxwood Manor, Formal Garden;

postcard. LHSA

Boxwood Manor, Apple Blossoms; postcard. LHSA

[1] J. W. Dows, Boxwood Manor, Lyme, to Mrs. R. B. Mather, Norwich, May 12, 1932. LHSA

[2] Mr. Griswold distributed his photography equipment in his will. Old Lyme Probate Records, 5:153, July 6, 1904.

[3] The North American Review (1896), p. 772.

[4] “Old Lyme, The Beautiful; Resort of Many Artists,” The New London Day, August 18, 1904; Art Students League, Letter Book, Lyme, Connecticut; photocopy. LHSA

[5] “Woodrow and Ellen Axson Wilson in Old Lyme: Online Learning Site,” Florence Griswold Museum, 2012.

[6] “Boxwood School Closed,” The New London Day, October 16, 1907; The New London Day, August 29, 1910. On April 17, 1908, The Sound Breeze reported: “Mrs. L. L. Foote of 34 W. 82nd Street, NYC, has leased the Boxwood for the summer. Mrs. Foote has kept a select and successful boarding house at the above address for several years and was well recommended. The house will open for guests June 1.”

[7] Alumnae Record of Boxwood School (1913). LHSA. “Boxwood’s First Annual Week-End,” The New London Day, June 5, 1912.

[8] “Art at Home and Abroad,” The New York Times, September 7, 1913. Morning at Boxwood, which Titcomb exhibited in 1911 at the Pennsylvania Museum of Fine Arts, may be the original title of the painting later mistakenly called The Park Bench. The Internet Antique Gazette describes Titcomb’s Old Lyme paintings.

[9] Margaret Axson Elliott to Jessie Wilson Sayre, July 5, 1906, in Jessie Wilson Sayre Papers, MC216, Box 1, Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library; Barbara Lehman Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones: The Artist Who Lived Twice (2010), p. 65.

[10] Elizabeth Knudsen to Mr. Becker, March 12, 2001, LHSA; W. A. Cushing to Edmund Greacen, May 6, 1913, LHSA.

[11] Arts & Decoration, Vol. 8, page 287 (1917); The International Studio, Vol. 64, page 152 (June, 1918).

[12] Courtesy Ludington Family Collection.

[13] Joseph F. Newman, “Charles Vezin: Paint and Purpose,” The Cooley Gallery, 2007. Vezin exhibited A Corner at Boxwood in the Lyme summer exhibition in 1925, so he apparently painted a third view of the inn. A letter to Mary Pleissner in 1933 indicates that he was still working at Boxwood that year: “Vezin by Ogden M. Pleissner arrived yesterday morning, in a very large box,” he wrote. “It was so large and heavy that I had it laid flat on the piazza below the outside studio at Boxwood.”