by Carolyn Wakeman

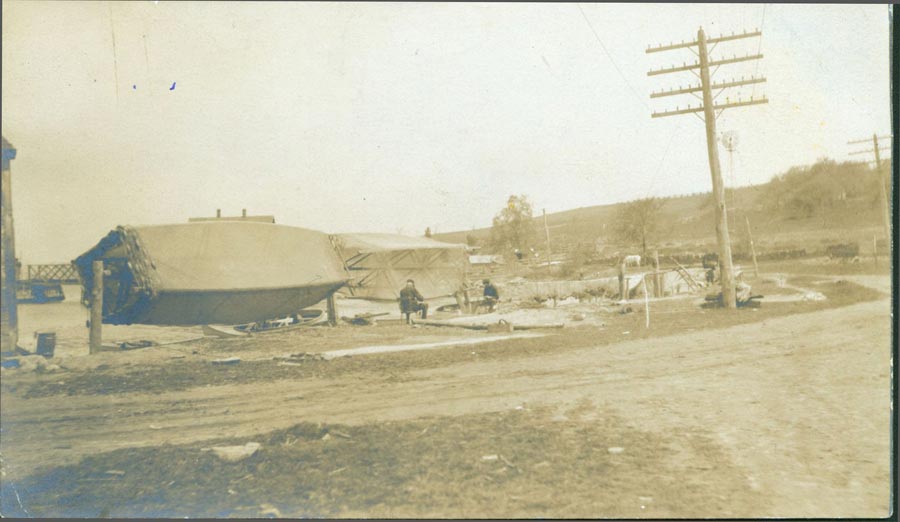

Feature Photo (above): Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Shad nets at Ferry Point, with Reuben Champion house and Enoch Noyes house, ca. 1885. LHSA

Shad nets stored on wooden reels were once a familiar sight along the Connecticut River. This photograph, taken ca. 1885 near the Reuben Champion house at Ferry Point, recalls the days when “shadding” was an important source of local income.

Shad Season in Lyme

During the two-month run from mid-April to mid-June when shad hurtled up the Connecticut River to spawn, Lyme farmers turned fishermen. Using cumbersome nets that stretched a quarter of a mile across the river, they hauled out hundreds of silvery fish at night on an incoming tide. What they earned during the shad season could exceed a whole year’s income from farming.[1]

For town constable, tax collector, and selectman Henry Noyes (1826-1917), who grew up on Ferry Point, shad fishing supplemented not just farming but also boat building. His account book lists fifteen boats, including two sloops, two scows, and a motor launch, built together with his son John Ely Noyes (1862-1948) between 1883 and 1907.[2] But before Henry Noyes settled permanently to farm, fish, and build boats in Old Lyme, he left home at age 24 to seek his fortune.

Mending shad nets at Ferry Point. LHSA

The oldest son of Enoch Noyes (1789-1877), Henry attended the Lyme Academy and worked for a few years on his father’s farm. Then he caught “gold fever” and in 1850 traveled via the Isthmus of Panama to join thousands of adventurers streaming to California after gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. In addition to prospecting for gold, he fished for salmon in Oregon and Washington and sometimes earned $100 a day hunting for big game.[3] After eleven years in the West and four years in Baltimore where he married a cousin, Noyes returned home. In 1867 he bought the house built by Richard Lord (1752-1818) in 1790 in the area now called Tantummahaeg. He also purchased sixty acres of farmland and forty acres of salt meadow on nearby Goose Island[4] where shad fishing had long been profitable.

Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Henry Noyes house at Tantummahaeg, ca. 1885. LHSA

Shad Profits

Before 1750 Connecticut shad had limited use. Shad were either spread across fields as fertilizer or barreled, salted, and shipped to the West Indies as cheap food for slaves working the sugar plantations. Eating the strong-smelling local fish was considered “disreputable.”

The reluctance to eat shad changed after it became a staple food for the Continental army during the Revolutionary War.[5] As demand grew for prime shad caught near the mouth of the Connecticut River, enterprising “Lymeites” recognized a commercial opportunity. Among them were Governor Roger Griswold’s sons.

Fishing was already profitable in 1809 off Poverty Point when Charles Griswold (1791-1839) wrote to his older brother Augustus about a night’s work during shad season: “Last Night I was up to my Knuckles in Shad-guts in which we plunged ourselves pretty deep, we dressed & salted nearly 3 barrels & took us ‘till nine oclock. The Poverty trade is quite extensive, we have caught almost 12,000 so far this Spring & are easily adding to the number, we might have vended last week 10,000 if we had had them, such is the Demand, they go at 8 cts. this season, whilst last year only for 6.”[6] But it was Charles’ younger brother Matthew Griswold (1792-1879) who ran the shad fishing business in Black Hall. According to a family memoir, Matthew “was an extensive and successful proprietor of shad fisheries in the mouth of the river, where he used to go out with his boats and nets to a pier and catch large quantities of the favorite Connecticut River shad. I have been told than whenever a thousand shad were caught at one haul, they used to fire a gun from the pier to announce the fact.”[7]

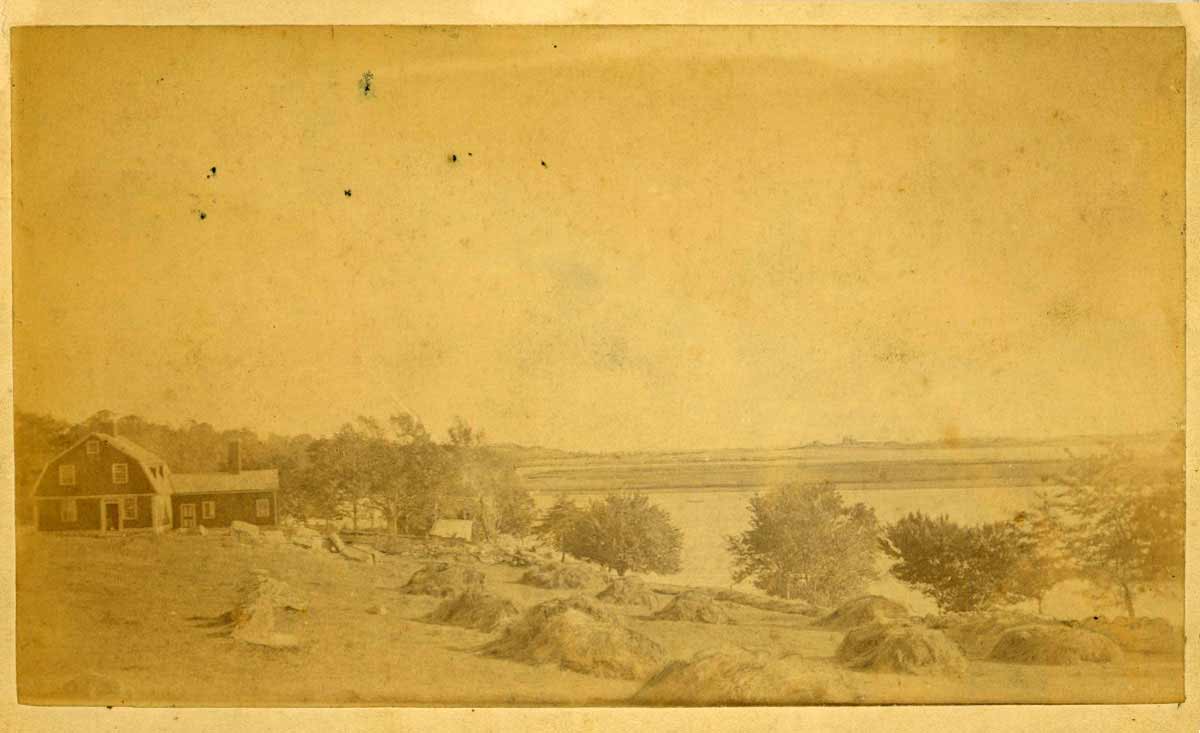

Richard Sill Griswold, Jr., Enoch Lord house, looking south across Goose Island, ca. 1885. LHSA

Goose Island Fish Company

70-acre Goose Island had been part of the Lord family’s extensive landholdings along the Connecticut River from the town’s original settlement. Stephen J. Lord (1797-1851), who owned a general merchandise store in the village, developed an early family fishery on the island’s southern end[8] into a profitable business that lasted more than thirty years. The Goose Island Fish Company’s financial records trace the history of commercial shad fishing in Lyme.[9]

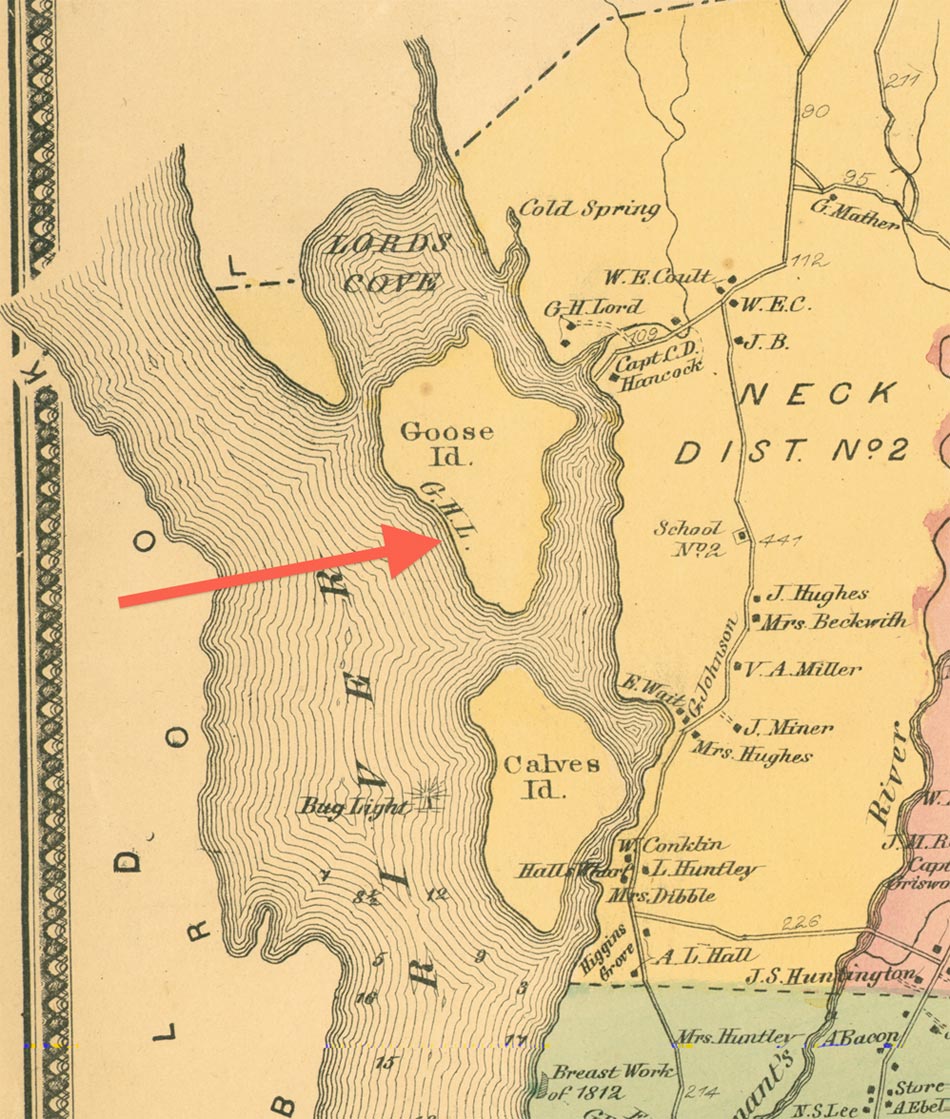

Town of Old Lyme (detail showing Goose Island and Lord’s Cove). F. W. Beers, 1868. LHSA

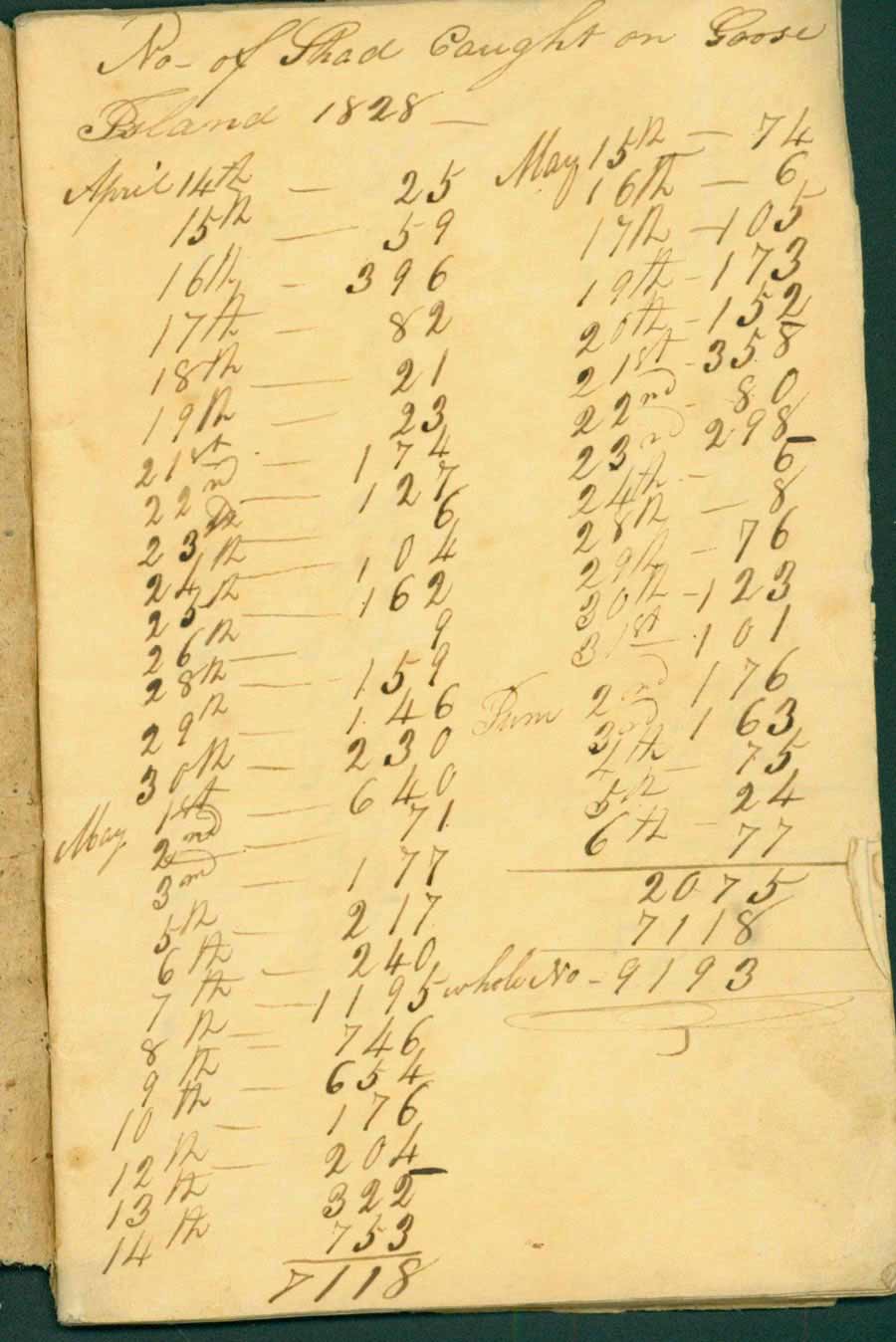

The company’s earliest surviving account book itemizes 7,839 shad caught at Goose Island in 1822. Over the next six years the yield more than doubled, and in 1828 Lord employed eight fishermen who caught a total of 15,799 shad, of which 9,193 were caught off Goose Island and 6,606 from a fishing pier. Two decades later the company employed eighteen fishermen, but by then the supply of shad had slowed. The 1848 account book records 10,349 shad caught at Goose Island, and after that season Lord remarked to an investor that the fishery had been “unproductive for several years past.”[10]

Almon Bacon, a local steamer captain who transported the company’s fish from Higgins Wharf, reported a sharp drop in the New York shad market in 1849:

“By your request I address you in relation the Fish Market in N.Y. and must say that I never knew it much worse, not many Shad in New York in their Hands but there is two Vessels in the City with Shad which are unsold, all they get offered is 4.50 for No 2, 5.50 for No 1 and they say that they will not sell at that price.”[11] Two weeks later Stephen Lord’s business partner and childhood friend William Noyes (1792-1873), then living in Troy, confirmed the New York market shift. The quality of Connecticut River shad had declined, he wrote, while competition from other eastern suppliers had increased and tastes had changed. In fact, Noyes himself preferred to eat pickled salmon.

Goose Island Fish Company account book, 1828. LHSA

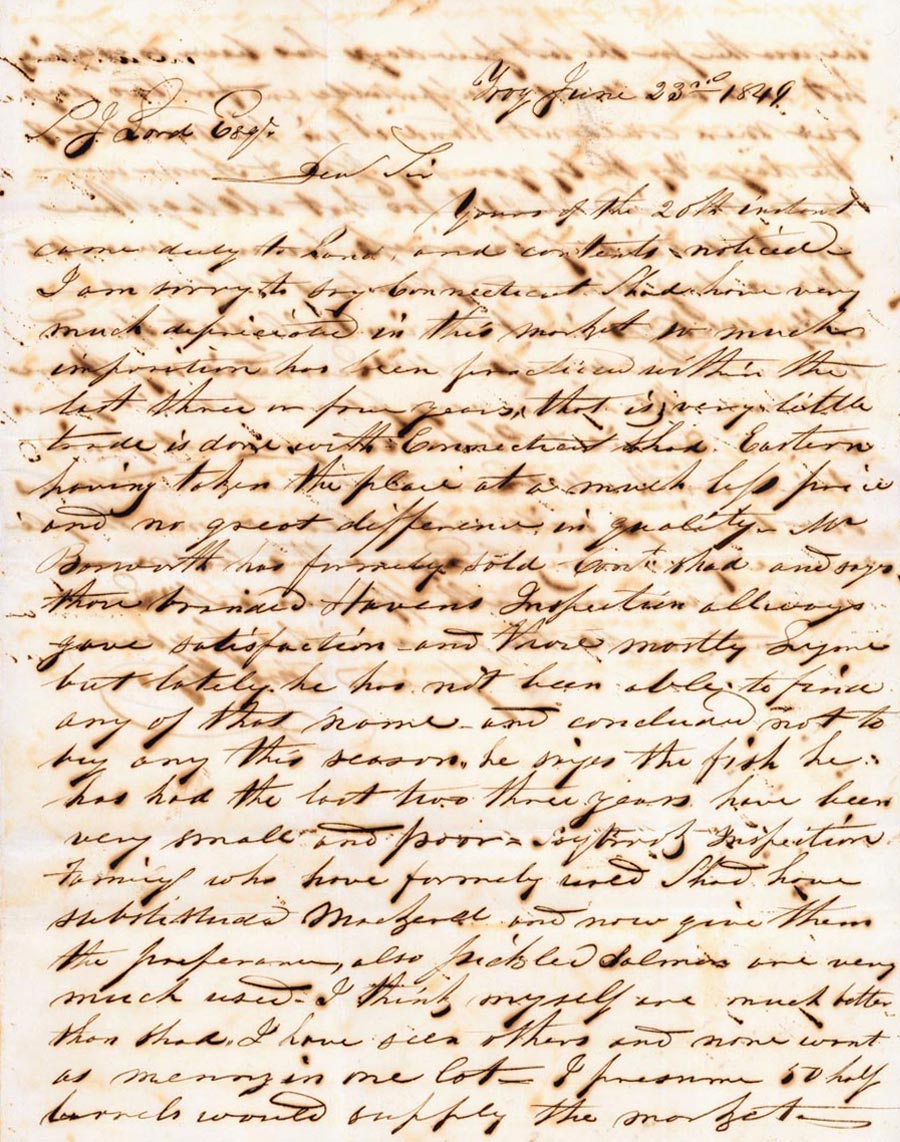

William Noyes to Stephen J. Lord, June 23, 1849. LHSA

Dear Sir . . . .I am sorry to say Connecticut Shad have very much depreciated in this market . . . within the last three or four years. That is, very little trade is done with Connecticut Shad, Eastern having taken the place at a much less price and no great difference in quality. Mr Bosworth has formerly sold Cont shad and says those branded Havens Inspection always gave satisfaction, and those mostly Lyme, but lately he has not been able to find any of that name and concluded not to buy any this season. He says the fish he has had the last two three years have been very small and poor — Saybrook Inspection Family who have formerly sold Shad have substituted Mackerel and now give them the preferance, also pickled Salmon are very much used, I think myself are much better than shad. I have seen others and none want as many in one lot – I presume 50 half barrels would supply the market. . . . accept the good wishes of your friend Wm Noyes [12]

Henry Noyes house at Ferry Point, ca. 1910. LHSA

After the Fisheries

Large-scale commercial fishing in Lyme ended before the Civil War, and barreled shad were no longer shipped in bulk from Higgins’ Wharf to New York for distribution. But the shad run continued to provide a seasonal income in 1905 when Henry Noyes, age 79, sold his Lord’s Cove house and property, including his Goose Island acreage, and purchased the Reuben Champion house (now demolished) on Ferry Point. That same year, settled on land adjoining the farm where he grew up,[13] he sold two boats, one to David Huntley for $65.00 and a scow to Judge Walter C. Noyes for $50.00.

Today Lyme’s shad reels have disappeared, but the remains of four stone fishing piers are said to be visible along the western flank of Calves Island.[14] And the public landing at Tantummahaeg, for which Stephen Lord’s ancestors petitioned the town in 1701,[15] still provides access to Lord’s Cove.

Shad reel along Lieutenant River postcard. LHSA

Tantummahaeg Town Landing

[1] Carlin Kindilien, “Of Ships and Shad,” in Hamburg Cove, ed. Stanley Schuler (Florence Griswold Museum, 1993), pp. 88-92.

[2] Henry Noyes and John Noyes, Account Book (copy), Ely-Plimpton Papers, Box 6, Lyme Historical Society-Florence Griswold Museum (LHSA).

[3] Genealogical and Biographical Record of New London County (Chicago, 1905), p. 720; “Had a Varied Career,” The Day, June 19, 1917.

[4] Old Lyme Land Records 2:175.

[5] Edmund Delaney, The Connecticut River: New England’s Historic Waterway (Chester, 1983), p. 100; Douglas D. Moss, “A History of the Connecticut River and Its Fisheries” (n.d.), pp. 4-5, Misc. 2:73, LHSA; Charles A. Goodwin, “Pilot’s Guide to the Mouth of the Connecticut River” (1944), Misc. 2:37, LHSA; Jack Noon, “History of a Fishery,” in W. D. Wetherell, ed., This American River: Five Centuries of Writing about the Connecticut (UPNE, 2002), pp. 239-240; John McPhee, The Founding Fish (New York, 2002), pp. 157-9, 174.

[6] Chas Griswold to Augustus H. Griswold, May 16, 1809, Courtesy Old Lyme Historical Society.

[7] Adeline Bartlett Allyn, Black Hall: Traditions and Reminiscences (Hartford, 1908), p. 57.

[8] “Captain Enoch Lord House,” National Register of Historic Places (2006), pp. 2-3.

[9] Account books and receipts for the Goose Island Fish Company are collected in Lord Family Papers, Box 10a, LHSA.

[10] Stephen J. Lord to Jacob B. Gurley, July 15, 1848, Lord Family Papers, Box 4, LHSA.

[11] Almon Bacon to Stephen J. Lord, June 17, 1849, Lord Family Papers, Box 4, LHSA. In 1828 the average price per barrel in New York was $7.79, while in 1835, after a particularly cold and unfavorable start to the season, the New York price was $6.00 per barrel.

[12] William Noyes to Stephen J. Lord, June 23, 1849, Lord Family Papers, Box 4, LHSA. Noyes retained a part ownership in the Goose Island Fish Company until 1848.

[13] Old Lyme Land Records 5:561

[14] John S. Hall, “A History of Calves Island” (privately published, 1991), p. 6.

[15] “Captain Enoch Lord House,” p. 7.